Joseph Locke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joseph Locke

|

|

|---|---|

Joseph Locke

|

|

| Born | 9 August 1805 Attercliffe, Sheffield, Yorkshire

|

| Died | 18 September 1860 (aged 55) |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Civil engineer |

| Significant advance | Railway |

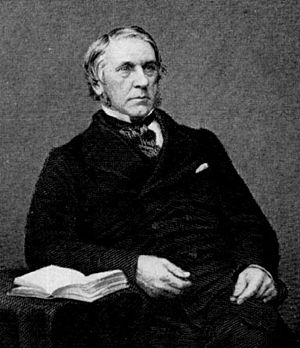

Joseph Locke (born August 9, 1805 – died September 18, 1860) was a very important English civil engineer in the 1800s. He is best known for his amazing work on railways. Locke was one of the top railway pioneers, alongside famous engineers like Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Contents

- Early Life and First Steps in Engineering

- Building the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

- The Grand Junction Railway Project

- Marriage and Recognition

- Building Railways in the North: Lancaster and Carlisle Railway

- Other Important Railway Projects

- Friendship with Robert Stephenson

- Later Life and Lasting Impact

Early Life and First Steps in Engineering

Joseph Locke was born in Attercliffe, Sheffield, in Yorkshire. When he was five, his family moved to Barnsley. By the time he was 17, Joseph was already a skilled mining engineer. He knew how to survey land, dig mine shafts, and build railways, tunnels, and engines.

His father, William, had worked with George Stephenson at a coal mine. In 1823, George Stephenson was planning the Stockton and Darlington Railway. He and his son, Robert Stephenson, met Joseph and his father. It was decided that Joseph would go to work for the Stephensons. They had a factory in Newcastle upon Tyne that made locomotives for the new railway. Even though Joseph was young, he quickly became an important person there. He and Robert Stephenson became very good friends. However, their friendship was put on hold when Robert went to work in Colombia for three years in 1824.

Building the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

George Stephenson first surveyed the route for the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. But his survey had problems. A talented young engineer named Charles Vignoles re-surveyed the line. Joseph Locke was then asked to check the plans for the tunnels and write a report. His report was quite critical of Stephenson's earlier work. This made Stephenson very angry, and their relationship became difficult. However, Stephenson still kept Locke working for him, likely because he knew how valuable Joseph was.

Even with the criticisms, the plan for the new railway was approved in 1826. Stephenson became the chief engineer, and he chose Joseph Locke as his assistant, working with Vignoles. But Stephenson and Vignoles didn't get along, so Vignoles left. This made Locke the only assistant engineer. Locke took charge of the western half of the railway line.

One of the biggest challenges was crossing Chat Moss, a huge bog (a type of wetland). While Stephenson often gets the credit for this, many believe it was Locke who figured out the best way to build a railway across the bog.

While the railway was being built, the directors had to decide if they should use stationary engines (fixed engines pulling trains with ropes) or locomotives (moving engines). Robert Stephenson and Joseph Locke were sure that locomotives were much better. In March 1829, they wrote a report showing how much better locomotives would be for a busy railway. This report led the directors to hold a competition to find the best locomotive. This famous event was called the Rainhill Trials, held in October 1829. The locomotive "Rocket" won the competition.

The railway finally opened in 1830. A procession of eight trains was planned to travel from Liverpool to Manchester and back. George Stephenson drove the main locomotive, "Northumbrian", and Joseph Locke drove "Rocket". Sadly, the day was marked by a tragic accident. William Huskisson, a Member of Parliament for Liverpool, was accidentally hit by "Rocket" and passed away.

The Grand Junction Railway Project

In 1829, Joseph Locke was George Stephenson's assistant. He was given the job of surveying the route for the Grand Junction Railway. This new railway would connect Newton-le-Willows (on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway) to Warrington, and then continue to Birmingham through towns like Crewe, Stafford, and Wolverhampton. This was a long route, about 80 miles.

Locke is known for choosing the location for Crewe. He suggested building workshops there to make and repair railway carriages, wagons, and engines.

During the building of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, Stephenson had shown some difficulty in organizing very large construction projects. Locke, however, was known for his excellent management skills. The directors of the new Grand Junction Railway decided to split the work. Locke was in charge of the northern half of the line, and Stephenson was in charge of the southern half.

But Stephenson's organizational problems soon became clear. Locke, on the other hand, estimated the costs for his section so carefully and quickly that he had all his contracts signed before Stephenson had even signed one. The railway company became impatient with Stephenson. They tried to make both men joint chief engineers. Stephenson's pride wouldn't let him accept this, so he resigned from the project. By the autumn of 1835, Locke became the chief engineer for the entire line. This caused a disagreement between Locke and George Stephenson, and also strained his friendship with Robert Stephenson. From this point on, Locke was in charge of his own career and would be judged by his own successes.

The Grand Junction Railway opened on July 4, 1837.

New Ways of Building Railways

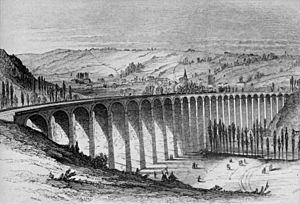

Locke's railway routes tried to avoid huge construction projects as much as possible. One major structure he did build was the Dutton Viaduct. This bridge crosses the River Weaver in Cheshire. It has 20 arches, each about 20 yards wide.

An important new feature on this railway was the use of special wrought-iron rails. These rails were supported on wooden sleepers (ties) every 2 feet 6 inches. The idea was that when one side of the rail wore out, it could be flipped over. However, the metal supports holding the rails caused wear on the bottom, making it uneven. Still, this was an improvement over older rail designs.

Locke was very careful with the railway company's money. For example, for the Penkridge Viaduct, Stephenson had received a bid of £26,000. After Locke took over, he gave the builder better information and agreed on a price of only £6,000. Locke also tried to avoid building tunnels. In those days, tunnels often took longer and cost more than planned. The Stephensons thought that a slope of 1 in 330 was the steepest an engine could handle. Robert Stephenson achieved this on the London and Birmingham Railway by using seven tunnels, which added cost and delays. Locke almost completely avoided tunnels on the Grand Junction line. He allowed steeper slopes for six miles south of Crewe, showing his confidence in modern locomotives.

Locke's ability to estimate costs accurately was impressive. The Grand Junction line cost £18,846 per mile, very close to Locke's estimate of £17,000. This was much more accurate than the cost estimates for other major railways of the time.

Locke also divided his projects into a few large sections instead of many small ones. This allowed him to work closely with his contractors. He could develop the best building methods, solve problems, and gain practical experience. He often worked with the same reliable contractors, like Thomas Brassey and William Mackenzie, on many other projects. This cooperative way of working benefited everyone.

Marriage and Recognition

In 1834, Joseph Locke married Phoebe McCreery. They adopted a child together. In 1838, he was elected to the Royal Society, a very important group for scientists and engineers.

Building Railways in the North: Lancaster and Carlisle Railway

There was a big difference in how George Stephenson and Joseph Locke thought about surveying railway routes. Stephenson started his career when locomotives weren't very powerful. Both George and Robert Stephenson would go to great lengths to avoid steep hills, even if it meant making the railway much longer. Locke, however, trusted that modern locomotives could climb steeper slopes.

A good example of this was the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, which had to cross the Lake District mountains. In 1839, Stephenson suggested a long route that went all the way around Morecambe Bay to avoid the mountains. He said building a railway over Shap Fell was impossible. But the directors rejected his idea and chose Locke's route. Locke's plan used steeper slopes and went right over Shap Fell. Locke completed the line, and it was a success.

Locke believed that by avoiding long routes and tunnels, a railway could be finished faster, cost less money, and start making money sooner. This approach became known as the 'up and over' method of engineering. Locke used a similar approach when planning the Caledonian Railway from Carlisle to Glasgow. On both railways, he included slopes of 1 in 75. These slopes were very challenging for fully loaded locomotives, even as more powerful engines were developed. Even today, Shap Fell is a difficult climb for trains.

Locke was also chosen to build a railway line from Manchester to Sheffield. This project included the three-mile-long Woodhead Tunnel. The line opened on December 23, 1845, after many delays. Building this line required over a thousand workers called navvies. Sadly, 32 of them lost their lives, and 140 others were seriously injured during the construction. The Woodhead Tunnel was so difficult that George Stephenson famously said it couldn't be done.

Other Important Railway Projects

In the north of England, Locke also designed the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway, the Glasgow, Paisley and Greenock Railway, and the Caledonian Railway connecting Carlisle to Glasgow and Edinburgh.

In the south, he worked on the London and Southampton Railway, which later became the London and South Western Railway. For this line, he designed structures like the Nine Elms to Waterloo Viaduct, the Richmond Railway Bridge (in 1848, later replaced), and the Barnes Railway Bridge (in 1849), both crossing the River Thames. He also built tunnels at Micheldever and two large viaducts in Fareham.

Locke was also very active in planning and building many railways in Europe, with help from John Milroy. These included the railway linking Le Havre, Rouen, and Paris in France, the line from Barcelona to Mataró in Spain, and the Dutch Rhenish Railway in the Netherlands. He was in Paris when the Versailles train crash happened in 1842 and provided information about the accident.

He also faced a major challenge when one of his viaducts on the new Paris-Le Havre line collapsed. This was the stone and brick viaduct at Barentin near Rouen. It was the longest and highest on the line, standing 108 feet tall with 27 arches. One morning, an arch collapsed, and then the rest followed. Luckily, no one was killed, though some workers nearby were injured. Locke believed the collapse was due to frost affecting the new cement and the bridge being loaded too early. It was rebuilt at the cost of his contractor, Thomas Brassey, and still stands today. After pioneering many new lines in France, Locke also helped set up the first locomotive factory in the country.

Key features of Locke's railway designs were saving money, using stone bridges whenever possible, and avoiding tunnels. For example, there are no tunnels between Birmingham and Glasgow on the railway lines he designed.

Friendship with Robert Stephenson

Locke and Robert Stephenson were good friends early in their careers. However, their friendship became difficult when Locke had a disagreement with Robert's father, George Stephenson. It seems Robert felt he had to support his father. It's interesting that after George Stephenson passed away in August 1848, the friendship between Locke and Robert was renewed. When Robert Stephenson died in October 1859, Joseph Locke was one of the pallbearers at his funeral. Locke reportedly called Robert "the friend of my youth, the companion of my ripening years, and a competitor in the race of life." Locke was also friendly with his other engineering rival, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

In 1845, Locke and Stephenson both gave important evidence to two committees. In April, a committee was looking into the atmospheric railway system that Brunel had suggested. Brunel supported it, while Locke and Stephenson spoke against it. In the long run, Locke and Stephenson were proven right. In August, they gave evidence to the Gauge Commissioners, who were trying to decide on a standard track width for all railways in the country. Brunel argued for the 7-foot width he used on the Great Western Railway. Locke and Stephenson argued for the 4-foot 8½-inch width they had used on many lines. Locke and Stephenson won, and their track width was adopted as the standard for the whole country.

Later Life and Lasting Impact

Joseph Locke served as the President of the Institution of Civil Engineers from December 1857 to December 1859. He was also a Member of Parliament for Honiton in Devon from 1847 until his death. A Member of Parliament is a person elected to represent a group of people in the country's main law-making body.

Joseph Locke passed away on September 18, 1860, seemingly from appendicitis, while on a hunting trip. He is buried in London's Kensal Green Cemetery. He died less than a year after his friends and rivals, Robert Stephenson and Isambard Brunel. All three engineers died between the ages of 53 and 56. Some believe this was due to working too hard, achieving so much in their relatively short lives.

Locke Park in Barnsley was created in his memory by his wife, Phoebe, in 1862. It has a statue of Locke and a tower called 'Locke Tower'.

Locke's biggest legacy is the modern-day West Coast Main Line (WCML). This major railway line was formed by joining the Caledonian, Lancaster & Carlisle, and Grand Junction railways with Robert Stephenson's London & Birmingham Railway. Because of Locke's work, about three-quarters of the WCML's route was planned and built by him.

|

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |