Thomas Brassey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Brassey

|

|

|---|---|

Brassey by Frederick Piercy, 1850

|

|

| Born | 7 November 1805 Buerton, Chester, England

|

| Died | 8 December 1870 (aged 65) St Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex, England

|

| Occupation | Civil engineering contractor |

| Spouse(s) |

Maria Harrison

(m. 1831) |

| Children |

|

Thomas Brassey (1805–1870) was an amazing English builder and engineer. He was responsible for building a huge part of the world's railways in the 1800s. By 1847, he had built about one-third of all the railways in Britain!

When he passed away in 1870, he had built one out of every twenty miles of railway on Earth. This included most of the lines in France and major lines in many other countries. He built railways in Europe, Canada, Australia, South America, and India. He also built all the important structures that go with railways, like bridges, tunnels, stations, and docks.

Besides railways, Brassey also worked on steamships, mines, and even water and sewage systems. He helped build part of London's sewer system, which is still used today. He was also a big investor in a giant ship called the Great Eastern. This ship was the only one big enough to lay the first telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1864. Thomas Brassey left a huge fortune, showing just how successful he was.

Contents

- Early Life and Learning

- Building Railways in Britain

- First Projects in France

- "Railway Mania" in Britain

- Building Across Europe

- The Grand Trunk Railway of Canada

- The Grand Crimean Central Railway

- Building Around the World

- Other Building Projects

- How He Worked

- Family Life

- Later Years

- Remembering Thomas Brassey

- Statue

- See also

Early Life and Learning

Thomas Brassey was the oldest son of John and Elizabeth Brassey. His father was a successful farmer. The Brassey family had lived in a small village called Buerton, near Chester, for a long time.

Thomas was taught at home until he was 12. Then he went to The King's School in Chester. At 16, he started an apprenticeship with William Lawton, a land surveyor. A surveyor measures land and plans building projects.

During his apprenticeship, Thomas helped survey a new road from Shrewsbury to Holyhead. This is now the A5. He even met a famous engineer named Thomas Telford during this time. When he finished his training at 21, Brassey became Lawton's business partner. They formed the company "Lawton and Brassey."

Thomas moved to Birkenhead, a very small town back then. Their business grew quickly. They built a brickworks and lime kilns. They also owned or managed sand and stone quarries. Brassey even found new ways to move materials, like using a system similar to modern pallets. He also used a special "gravity train" to move materials from the quarry to the port. When Lawton died, Brassey took over the whole company. These years gave him all the basic skills he needed for his future career.

Building Railways in Britain

Thomas Brassey's first building projects were a road and a bridge on the Wirral. During this time, he met George Stephenson, a famous railway engineer. Stephenson suggested Brassey get involved in building railways.

Brassey tried to get a contract to build the Dutton Viaduct but didn't win it. However, in 1835, he won a contract to build the Penkridge Viaduct and ten miles of track for the Grand Junction Railway. This project was a big success! The viaduct opened in 1837 and is still used today by trains on the West Coast Main Line.

After this, Brassey worked with Joseph Locke, another important engineer. He built parts of the London and Southampton Railway. The next year, he won contracts for the Chester and Crewe Railway and the Glasgow, Paisley and Greenock Railway.

First Projects in France

After railways became popular in Britain, France wanted its own railway system. Joseph Locke, who worked with Brassey, was hired as an engineer for the Paris and Rouen Railway. He thought French builders were too expensive. So, he invited British builders to bid.

Thomas Brassey and William Mackenzie decided to work together instead of competing. They won the contract in 1841. This became a common way for Brassey to work, partnering with other builders. Between 1841 and 1844, Brassey and Mackenzie built four French railways, totaling 437 miles. The longest was the 294-mile Orléans and Bordeaux Railway.

After a financial crisis in France in 1848, railway building slowed down. This made Brassey look for projects in other countries.

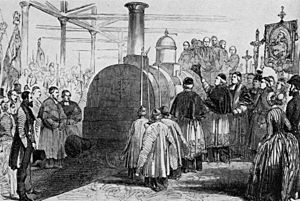

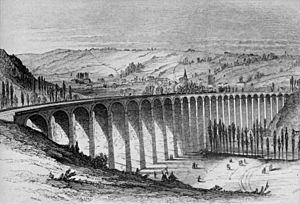

The Barentin Viaduct Collapse

In 1846, while building the Rouen and Le Havre line, one of the few big problems in Brassey's career happened. The Barentin Viaduct collapsed. This viaduct was 100 feet high and made of brick. No one was ever sure why it fell, but it might have been because of the type of lime used in the mortar. The contract said they had to use local lime, and the collapse happened after heavy rain.

Brassey rebuilt the viaduct at his own cost, using lime he chose himself. The rebuilt viaduct is still standing and is used today!

"Railway Mania" in Britain

While Brassey was building railways in France, Britain was going through "railway mania." This was a time when people invested a lot of money in building railways. Many lines were being built, but not all were built as well as Brassey's.

Brassey was part of this boom, but he was careful to choose good projects and investors. In 1845 alone, he agreed to nine contracts in England, Scotland, and Wales, totaling over 340 miles.

One of his greatest lines was the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, built with Locke. It went through the Lune Valley and over Shap Fell, a high and steep area. He also built the Trent Valley Railway and the Chester and Holyhead Railway. The Chester and Holyhead line included Robert Stephenson's famous Britannia Bridge over the Menai Strait.

In 1847, Brassey started building the Great Northern Railway. A big challenge was building on the marshy land of The Fens. Brassey's team found a way to create a strong foundation by sinking huge amounts of clay and gravel. This line is still part of the East Coast Main Line today. By the end of the "railway mania," Brassey had built one-third of all the railways in Britain.

Building Across Europe

After the "railway mania" ended in Britain and French projects slowed, Brassey could have retired. But he decided to build railways in other European countries.

His first project in Spain was the Barcelona and Mataró Railway in 1848. In 1850, he started his first project in Italy. This led to bigger contracts like the Turin–Novara line and the Central Italian Railway.

In Norway, Brassey built the Oslo to Bergen Railway with partners Sir Morton Peto and Edward Betts. This line went through very difficult mountains, rising to nearly 6,000 feet high. He also continued building in France and the Netherlands.

The Grand Trunk Railway of Canada

In 1852, Brassey took on his biggest project ever: building the Grand Trunk Railway in Canada. This line was 539 miles long, running from Quebec to Toronto.

The line crossed the Saint Lawrence River at Montreal using the Victoria Bridge. This was a tubular bridge designed by Robert Stephenson. At 1.75 miles long, it was the longest bridge in the world at the time! The bridge opened in 1859.

Building this line was very difficult. They needed a lot of money, and Brassey even went to Canada to ask for help. The harsh Canadian winter, with waterways frozen for half the year, also caused problems. Even though the railway was a great engineering success, the builders lost a lot of money on it.

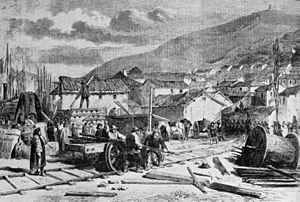

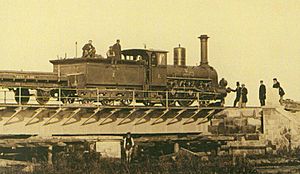

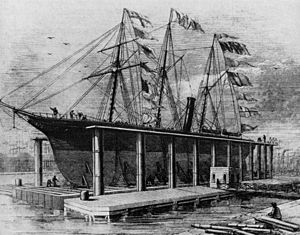

The Canada Works

The contract for the Grand Trunk Railway included everything needed, even the trains! To make the metal parts, Brassey built a huge new factory in Birkenhead called The Canada Works. It had a dock for ocean-going ships.

The factory was enormous, with a machine shop 900 feet long. It had blacksmiths' shops, coppersmiths' shops, and areas for woodworking. There was even a library and reading room for the workers!

The factory was designed to make 40 trains a year. In eight years, they produced 300 trains. The first train, tested in 1854, was named Lady Elgin. For the Victoria Bridge, hundreds of thousands of metal parts were made here. Every piece was perfectly made and fit together exactly.

The Grand Crimean Central Railway

Brassey also helped the British forces during the Crimean War. British soldiers were fighting in Sevastopol, Russia. They were based at Balaklava, a nearby port. It was very hard to get food, clothing, medicine, and weapons from Balaklava to the soldiers.

When Brassey heard about this problem, he teamed up with Peto and Betts. They offered to build a railway to transport supplies at cost (meaning they wouldn't make a profit). They sent equipment, materials, and a large group of workers called navvies. In just seven weeks, even in harsh winter conditions, the railway was finished! This made it easy to move supplies, and Sevastopol was finally captured in 1855.

Building Around the World

Besides Britain and Europe, Brassey also built railways on other continents. He built 250 miles of railways in South America, 132 miles in Australia, and 506 miles in India and Nepal.

In 1866, there was a big economic crisis. Many of Brassey's business partners and competitors went bankrupt. But Brassey managed to survive and kept working on his projects. He even continued building a railway in Galicia during a war!

From 1867, Brassey's health started to decline, but he kept working. He even took a long trip of over 5,000 miles in Eastern Europe in 1869. By the time he died, he had built one mile in every twenty miles of railway in the world.

Other Building Projects

Brassey didn't just build railways. He also built other important structures. He had factories in Birkenhead and France to make materials. He built drainage systems and a waterworks in Calcutta.

Brassey built docks in Greenock, Birkenhead, Barrow-in-Furness, and London. His London docks, the Victoria Docks, were huge, covering over 100 acres of water. They opened in 1857 and had links to Brassey's own railway line.

In 1861, Brassey built part of the London sewerage system for Joseph Bazalgette. This was a 12-mile stretch of sewer that is still used today. It was one of his most difficult projects. He also worked with Bazalgette to build the Victoria Embankment along the River Thames.

Brassey also helped fund Isambard Kingdom Brunel's giant ship, the Great Eastern. After Brunel died, Brassey and others bought the ship. They used it to lay the first Transatlantic telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean in 1864.

Brassey had many ideas ahead of his time. He tried to get governments interested in building a tunnel under the English Channel. He also wanted to build a canal through the Isthmus of Darién (now Panama). But these ideas didn't happen during his lifetime.

How He Worked

Thomas Brassey often worked with other builders, like Peto and Betts. Engineers planned the details of the projects. Brassey worked with famous engineers like Robert Stephenson, Joseph Locke, and Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

The daily work was managed by agents, who oversaw the subcontractors. The actual work was done by laborers, known as navvies, led by foremen. In the early days, many navvies had worked on canals. Later, workers from Scotland, Wales, and Ireland joined them.

Brassey paid his navvies well and provided food, clothing, and shelter. For projects overseas, he used local workers if possible, but British workers often helped. Brassey was very good at choosing skilled agents and trusting them with the work. He would give an agent money for a project. If the agent finished the work for less, they could keep the extra money. If unexpected problems came up, Brassey would cover the extra costs.

He had hundreds of agents working for him. At the peak of his career, for over 20 years, Brassey employed about 80,000 people in many countries!

Even with all this work, he didn't have a big office or staff. He handled all his letters himself, often writing many overnight. He had an amazing memory and was great at mental math. He was known for being fair and kind to his workers, even helping them financially when they needed it. He sometimes took on projects that didn't make him much money just to keep his navvies employed.

Brassey received many honors for his achievements, including the French Legion of Honour. He was a man of his word and always kept his promises. He wasn't interested in public fame and even refused invitations to become a Member of Parliament.

Historians say that Brassey helped make the job of a civil engineering contractor as respected as that of an engineer. He is seen as one of the most important figures of the 1800s.

Family Life

In 1831, Thomas married Maria Harrison. Maria was a great support to him throughout his career. She encouraged him to bid for contracts, even when he failed at first. Because of Thomas's work, they moved homes many times. Maria always managed the moves.

Maria's children had learned to speak French, but Thomas didn't. So, when French contracts came up, Maria acted as his interpreter. She encouraged him to take on these big projects. They moved to France for a while, and Maria translated for all his French business. Maria also made sure their three sons received a good education.

They had three sons who became successful in their own ways:

- Thomas Brassey, 1st Earl Brassey (1836–1918): He became a Member of Parliament and later the Governor of Victoria (in Australia). He was given the title of Earl Brassey.

- Henry Arthur Brassey (1840–1891): He also became a Member of Parliament.

- Albert Brassey (1844–1918): He was a rower, a soldier, and a Member of Parliament.

Later Years

In 1870, Thomas Brassey found out he had cancer, but he still kept visiting his work sites. One of his last visits was to a railway project near where he had his very first railway contract. In the late summer of 1870, he became very ill at his home. Many of his workers, including his engineers and navvies, came to visit him and show their respect. Some even walked for days to see him.

Thomas Brassey passed away on December 8, 1870, from a brain haemorrhage. He was buried in the churchyard of St Laurence's Church, Catsfield, Sussex. His estate was valued at over £5 million, making him one of the wealthiest self-made people of his time.

Remembering Thomas Brassey

None of Thomas Brassey's sons continued his building business. His sons created a memorial to their parents in St Erasmus' Chapel in Chester cathedral. It includes a bust (a sculpture of his head and shoulders) of their father. There is also another bust of Thomas in Chester's Grosvenor Museum and plaques at Chester station. Streets in Chester are named after him, like Brassey Street.

In November 2005, Penkridge celebrated 200 years since Brassey's birth with a special train ride. In 2007, a plaque was placed on Brassey's first bridge at Saughall Massie. In the village of Bulkeley, there's a tree called the 'Brassey Oak' that was planted to celebrate his 40th birthday in 1845.

In 2019, a blue plaque was put on the remaining part of his Canada Works building in Birkenhead.

Statue

The Thomas Brassey Society is planning to put up a statue of Thomas Brassey outside Chester Railway Station. They are currently raising money for it.

See also

- List of structures built by Thomas Brassey.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |