Lime kiln facts for kids

A lime kiln is like a giant oven used to make a special material called quicklime. Quicklime is made by heating a rock called limestone. Limestone is also known as calcium carbonate.

When limestone gets very hot, it changes. This process is called calcination. It turns into quicklime and releases a gas called carbon dioxide. Think of it like this:

- Limestone (CaCO3) + heat → Quicklime (CaO) + Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

Limestone is put into one side of the kiln. Hot air heats it up, and quicklime comes out the other side. Any waste gases go out through the top of the kiln.

Contents

Types of Lime Kilns

Lime kilns that were built to stay in one place usually fall into two main types. These are "flare kilns" and "draw kilns."

Flare Kilns

Flare kilns are also known as "intermittent" or "periodic" kilns. This means they work in batches. First, a layer of coal or wood was placed at the bottom. Then, the kiln was filled only with limestone. The fire would burn for several days. After the burning was finished, the whole kiln was emptied of the quicklime.

Draw Kilns

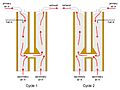

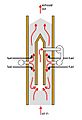

Draw kilns are also called "perpetual" or "running" kilns. These kilns could work continuously. They were usually made of stone. Limestone was layered with fuel like wood, coal, or coke. The fire was lit, and as it burned, quicklime was taken out from the bottom. More layers of stone and fuel were added to the top, so the kiln could keep running.

How Early Kilns Worked

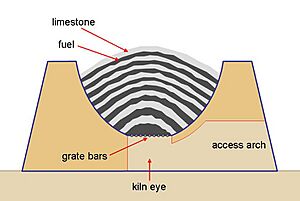

Early lime kilns often had a burning area shaped like an egg cup. It was built with bricks and had an opening at the bottom for air, called the "eye." Workers would crush limestone into pieces about 20 to 60 millimeters (about 1 to 2.5 inches) in size. Smaller pieces were not used.

They would then build up layers inside the kiln. First, a layer of limestone, then a layer of wood or coal, and so on. These layers were placed on metal bars across the air opening. Once the kiln was full, the fire was started at the bottom. The fire slowly moved upwards through the layers. When everything was burned, the quicklime was cooled down and pulled out from the bottom. Any fine ash would fall out and be removed.

Only lumpy pieces of stone could be used. This was because the layers needed to have space for air to flow through during the burning. This also limited how big the kilns could be. If a kiln was too wide, the hot limestone might collapse, putting out the fire. So, these kilns usually made about 25 to 30 tonnes (about 27 to 33 tons) of quicklime in one batch.

It usually took about a week to complete one batch:

- One day to load the kiln.

- Three days for the fire to burn.

- Two days for the quicklime to cool down.

- One day to unload the kiln.

Workers learned how much fuel to use by trying different amounts for each batch. Because the temperature was not the same everywhere inside the kiln, the quicklime produced was a mix. Some parts were not fully burned, some were just right, and some were over-burned. These early kilns were not very fuel-efficient. They often used about half a tonne (about 1,100 pounds) or more of coal for every tonne of quicklime made.

Sometimes, quicklime was made on a large scale. For example, at Annery in North Devon, England, there was a group of three kilns. They were located next to the Torrington canal and the River Torridge. This made it easy to bring in limestone and coal by water. It also helped transport the quicklime away before good roads existed.

It was common to see groups of seven kilns working together. One team would load the kilns, and another team would unload them. They would work on different kilns throughout the week. A kiln that was rarely used was sometimes called a "lazy kiln."

Lime Kilns in Great Britain

The large kiln at Crindledykes near Haydon Bridge, Northumbria, was one of over 300 in that area. It was special because it had four openings at the bottom to pull out the quicklime. Later, as less quicklime was needed, two of these openings were closed. But in 1989, English Heritage restored them.

As the national rail network grew, smaller local kilns became less profitable. They slowly disappeared during the 1800s. Larger industrial factories took their place. At the same time, new uses for quicklime appeared in the chemical, steel, and sugar industries. This led to even bigger factories and the creation of more efficient kilns.

A lime kiln built in Dudley, West Midlands (which was once part of Worcestershire), in 1842, is still standing today. It is part of the Black Country Living Museum, which opened in 1976. The kilns were last used in the 1920s. This kiln is one of the last remaining in an area that was once famous for coal and limestone mining until the 1960s.

Lime Kilns in Australia

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, a town called Waratah in Gippsland, Victoria, Australia, made most of the quicklime used in Melbourne. It also supplied other parts of Gippsland. This town, now called Walkerville, was on a remote part of the coast. The quicklime was shipped out by sea. When shipping became too expensive in 1926, the kilns were closed. Today, Walkerville is a tourist spot, and you can still see the ruins of the old lime kilns.

A lime kiln also existed in Wool Bay, South Australia.

Lime Kilns in Belgium

Images for kids

-

A traditional lime kiln in Sri Lanka.

-

Lime kilns in Porth Clais, Wales, in 2021.

-

A lime kiln in Untermarchtal, Baden-Württemberg.

-

A lime kiln from 1906 at Simplon, Namibia.

See also

In Spanish: Horno de cal para niños

In Spanish: Horno de cal para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |