Transatlantic telegraph cable facts for kids

Transatlantic telegraph cables were special underwater cables that stretched across the Atlantic Ocean. They were used for sending telegraph messages. Telegraphy is an old way of communicating, and these cables are no longer used. However, today's phone calls and internet data still travel across the Atlantic on modern undersea cables.

The very first cable was laid in the 1850s. It went from Valentia Island in Ireland to Bay of Bulls in Newfoundland. The first messages were sent on August 16, 1858. But the connection was not very good. Efforts to make it better actually caused the cable to break after only three weeks.

The Atlantic Telegraph Company built this first cable. Cyrus West Field led the project. It started in 1854 and finished in 1858. Even though it only worked for a short time, it was the first time such a project actually worked! The first official message sent across the ocean was a congratulation from Queen Victoria to President of the United States James Buchanan. This happened on August 16.

The signal quality quickly got worse, making messages very slow. The cable broke the next month. This happened when Wildman Whitehouse tried to send too much electricity through it. Some people believe the cable was poorly made and handled, so it might have broken anyway. Its short life made people lose trust and delayed future attempts.

A second cable was laid in 1865. This one used much better materials. The huge ship SS Great Eastern laid it. But more than halfway across, this cable also broke. After many tries, it was left behind.

In July 1866, a third cable was laid. Again, the Great Eastern sailed from Ireland to Heart's Content, Newfoundland. On July 27, this new connection successfully started working! The broken 1865 cable was also found and fixed. So, two cables were now working. These cables were much stronger.

Messages could be sent very quickly. People used the slogan "Two weeks to two minutes." This showed how much faster it was than sending messages by ship. The cable changed how people, businesses, and governments communicated across the Atlantic forever. Since 1866, there has always been a cable connection between the continents.

By the 1870s, new systems allowed many messages to be sent over the cable at the same time. Before the first transatlantic cable, messages between Europe and America traveled only by ship. This could take weeks, especially in bad winter storms. With the cable, a message and its reply could be sent on the same day!

Contents

- Early Ideas for an Ocean Cable

- The Plan Takes Shape

- The First Transatlantic Cable (1858)

- First Contact and Celebration

- Problems with the First Cable

- Preparing for a New Attempt

- The Great Eastern and the Second Cable

- Repairing Broken Cables

- Communication Speeds

- Later Cables

- Impact of the Cables

- See also

Early Ideas for an Ocean Cable

In the 1840s and 1850s, many people thought about building a telegraph cable across the Atlantic. Samuel F. B. Morse, who invented Morse code, believed it was possible as early as 1840. By 1850, a cable already connected England and France.

That same year, Bishop John T. Mullock in Newfoundland suggested a telegraph line. It would go through the forest from St. John's to Cape Ray. Then, cables would cross the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Nova Scotia.

Around the same time, Frederic Newton Gisborne, a telegraph engineer in Nova Scotia, had a similar idea. In 1851, he got permission from the Newfoundland government. He formed a company and began building the land line.

The Plan Takes Shape

In 1854, a businessman named Cyrus West Field invited Gisborne to his home. They talked about the project. Field then thought: what if the cable to Newfoundland could go even further, across the whole Atlantic Ocean?

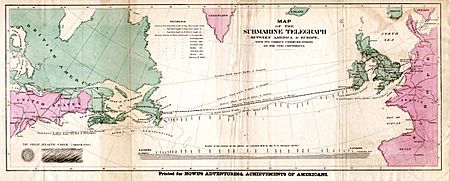

Field did not know much about undersea cables or the deep sea. He asked Morse and Lieutenant Matthew Maury for advice. Maury was an expert on oceanography, the study of oceans. Maury's maps, made from ship measurements, showed a good path across the Atlantic. It seemed perfect for laying a cable. Maury even named it Telegraph Plateau. His maps also showed that a direct route to the US would be too rough and too long.

Field decided to use Gisborne's plan as a first step. He created the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company. Its goal was to build a telegraph line between America and Europe.

The first step was to finish the line between St. John's and Nova Scotia. Gisborne and Field's brother, Matthew, worked on this. In 1855, they tried to lay a cable across the Cabot Strait. A storm hit, and they had to cut the line to save the ship. In 1856, a special steamboat successfully laid the link from Cape Ray, Newfoundland, to Aspy Bay, Nova Scotia. This part of the project cost over $1 million. The transatlantic part would cost much more.

In 1855, Field crossed the Atlantic. He would make 56 such trips for this project! He went to meet John Watkins Brett, a top expert on submarine cables. Brett's company had laid the first ocean cable in 1850 across the English Channel. His other company laid a cable to Ireland in 1853, which was the deepest cable at that time. Field also needed to raise money, as he had not found much support in New York. All the companies that made submarine cables were in Britain.

Field pushed the project forward with great energy. Even before forming a company, he ordered 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km) of cable. The Atlantic Telegraph Company was formed in October 1856. Brett was president, and Field was vice president. Charles Tilston Bright became the chief engineer. Wildman Whitehouse, a doctor who taught himself about electricity, was made chief electrician. Field himself put in a quarter of the money. Other investors, mostly from Brett's company, bought the rest of the shares. A board of directors was formed, including William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin), a respected scientist. Thomson also advised on science. Morse, who owned shares in the Nova Scotia project, was also on the board as an electrical advisor.

The First Transatlantic Cable (1858)

The cable was made of 7 copper wires. Each wire weighed about 26 kg per kilometer. They were covered with three layers of gutta-percha, a rubber-like material. Then, it was wrapped with tarred hemp. Finally, a protective layer of 18 strands of iron wire was wrapped around it. The cable weighed almost 550 kg per kilometer. It was flexible and strong enough to handle many tons of tension.

Two English companies made the cable's outer armor. They were Glass, Elliot & Co. and R.S. Newall and Company. They had to work very fast. Later, they found that the two batches of cable were twisted in opposite directions! This meant they could not be easily joined. They fixed it with a special wooden bracket. But this mistake caused bad publicity for the project.

The British government gave Field money and loaned ships for laying the cable. Field also asked the U.S. government for help. A bill to give money passed the Senate by only one vote. It also passed in the House of Representatives and was signed by President Franklin Pierce.

The first attempt to lay the cable was in 1857, and it failed. The ships were converted warships: HMS Agamemnon from Britain and USS Niagara from the U.S. Both ships were needed because neither could carry all 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km) of cable alone.

They started laying the cable in Ireland on August 5, 1857. It broke on the first day but was found and fixed. It broke again over the deep Telegraph Plateau. The operation was stopped for the year. Three hundred miles of cable were lost. But 1,800 miles (3,300 km) were still enough to finish the job. During this time, Morse and Field had disagreements, and Morse left the project.

The cable kept breaking because it was hard to control the tension as it was laid. A new system was designed and tested in May 1858. On June 10, Agamemnon and Niagara tried again. Ten days later, they hit a severe storm. The ships were heavy with cable and struggled to stay upright. Thomson's electrical cabin was flooded.

The ships met in the middle of the Atlantic on June 25. They joined the cables from both ships. Agamemnon headed east towards Ireland, and Niagara headed west towards Newfoundland. The cable broke after only 3 nautical miles (5.6 km). It broke again after 54 nautical miles (100 km), and a third time after about 200 nautical miles (370 km) from each ship.

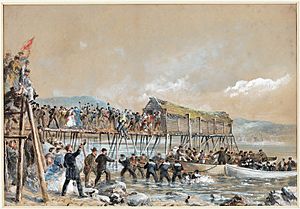

The ships returned to Ireland. Some directors wanted to give up, but Field convinced them to keep trying. The ships set out again on July 17. The middle splice was finished on July 29, 1858. This time, the cable laying went smoothly. Niagara reached Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, on August 4. The next morning, the cable was brought ashore. Agamemnon arrived at Valentia Island on August 5. The cable was brought ashore there too.

First Contact and Celebration

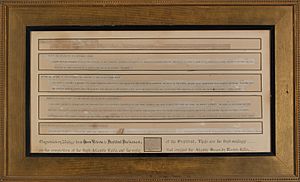

Test messages were sent from Newfoundland starting August 10, 1858. The first one was successfully read in Ireland on August 12. More tests followed until August 16. Then, the first official message was sent:

Directors of Atlantic Telegraph Company, Great Britain, to Directors in America:—Europe and America are united by telegraph. Glory to God in the highest; on earth peace, good will towards men.

Next came a congratulatory telegram from Queen Victoria to President James Buchanan. She hoped the cable would be "an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded on their common interest and reciprocal esteem." The President replied, calling it "a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle."

The messages were hard to understand. Queen Victoria's message of 98 words took 16 hours to send! Still, people were incredibly excited. The next morning, New York City fired 100 guns, hung flags, and rang church bells. At night, the city was lit up. On September 1, there was a parade and fireworks. Bright was made a knight for his work.

Problems with the First Cable

The 1858 cable had problems because of disagreements between Thomson and Whitehouse. Whitehouse, a doctor, had taught himself about electricity. He had no formal training. They argued even before the project began. Whitehouse disagreed with Thomson's ideas about how fast signals would travel. Thomson believed a thicker cable was needed, but Whitehouse supported a thinner, cheaper one.

Another argument was about how to lay the cable. Thomson wanted to start in the middle of the Atlantic. This would cut the laying time in half. Whitehouse wanted both ships to start from Ireland. Whitehouse was supposed to be on the cable-laying ship, but he kept finding excuses not to go. Thomson went in his place.

Thomson's Mirror Galvanometer

After the 1857 trip, Thomson realized they needed a better way to detect the telegraph signal. He invented the mirror galvanometer. This was a very sensitive tool. He asked for money to build more, but only got enough for one prototype. He successfully tested it on 2,700 miles (4,300 km) of cable.

The mirror galvanometer caused more arguments. Whitehouse wanted to use a high-voltage machine that produced thousands of volts. This would power standard printing telegraphs. Thomson's tool had to be read by eye. It could not print messages. Nine years later, Thomson invented the syphon recorder for the second transatlantic attempt.

Because Whitehouse avoided the voyage, Thomson was on board Agamemnon with his equipment. He was only an advisor, but soon all electrical decisions were left to him. Whitehouse stayed in Ireland and was out of contact. The board started to doubt Whitehouse because of his negative attitude and his refusal to do his job on the ship.

Cable Damage and Whitehouse's Dismissal

When Agamemnon reached Ireland on August 5, Thomson handed over to Whitehouse. The project was announced as a success. Thomson had received clear signals. But Whitehouse immediately connected his own equipment. The cable's poor handling and Whitehouse's repeated attempts to send up to 2,000 volts through it damaged the cable's insulation.

Whitehouse tried to hide the poor performance. The Queen's message was expected, and when it did not arrive, the press wondered what was wrong. Whitehouse said it would take weeks for "adjustments." The Queen's message had been received in Newfoundland, but Whitehouse could not read the confirmation copy sent back. Finally, on August 17, he announced he had received it. He did not say that he had to use Thomson's mirror galvanometer to read it. He then pretended it was received by his own printing telegraph.

In September 1858, the cable completely failed. People were shocked. Some even thought the whole thing was a trick. Whitehouse was called back for an investigation. Thomson took over in Ireland. Whitehouse was blamed for the failure and fired. The cable might have failed eventually anyway, but Whitehouse's actions certainly made it happen much sooner. The first hundred miles of cable from Ireland were especially weak. Tests showed that the copper wire inside was off-center in places. This made it easy for the wire to break through the insulation when the cable was laid.

Even though the cable never worked well for public use, a few important messages were sent. A ship collision was reported on August 17. The British government used the cable to cancel an order for two army groups in Canada to return to England. This saved £50,000. In total, 732 messages were sent before the cable broke.

Preparing for a New Attempt

Field was not discouraged by the failure. He wanted to try again, but the public had lost trust. It was not until 1864 that he managed to raise the money needed. With help from Thomas Brassey and John Pender, the Glass, Elliot, and Gutta-Percha Companies joined to form the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company (Telcon). This new company would make and lay the new cable. C. F. Varley replaced Whitehouse as chief electrician.

By this time, long cables had been laid in the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. With this experience, a better cable was designed. The new cable was much stronger and heavier. It weighed almost twice as much as the old one. It was made with very pure copper and covered with many layers of gutta-percha and other protective materials.

The Great Eastern and the Second Cable

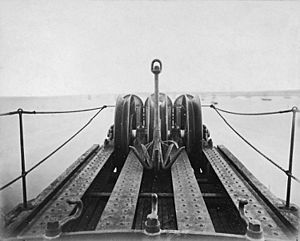

The new cable was laid by the huge ship SS Great Eastern. It had three large tanks to hold 2,300 nautical miles (4,300 km) of cable. On July 15, 1865, the Great Eastern left for Ireland. This attempt failed on August 2. After 1,062 miles (1,968 km) of cable were laid, it snapped near the ship's stern and was lost.

The Great Eastern went back to England. Field formed a new company, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company. Its goal was to lay a new cable and fix the broken one. On July 13, 1866, the Great Eastern started laying cable again. Despite bad weather, on July 27, the ship reached Heart's Content, Newfoundland.

Daniel Gooch, the chief engineer, sent a message to the British Secretary of State. He said, "Perfect communication established between England and America; God grant it will be a lasting source of benefit to our country." The next morning, a message from England quoted The Times newspaper: "It is a great work, a glory to our age and nation, and the men who have achieved it deserve to be honoured among the benefactors of their race." Congratulations poured in, and Queen Victoria and the United States exchanged friendly telegrams again.

In August 1866, several ships, including the Great Eastern, went back to sea. Their goal was to find the lost 1865 cable. They wanted to find its end, connect it to new cable, and finish the line to Newfoundland. Many thought it was impossible to find a cable 2.5 miles (4 km) deep. It was like "looking for a small needle in a large haystack."

However, Robert Halpin, an officer on the Great Eastern, guided the ships to the right spot. A grappling ship called Albany slowly "fished" for the lost cable with a five-pronged grappling hook. On August 10, Albany "caught" the cable and brought it to the surface! It seemed too easy. But during the night, the cable slipped away. They had to start all over again. This happened several times.

Finally, in early September 1866, the cable was retrieved. It took 26 hours to get it safely on board the Great Eastern. The cable was brought to the electrician's room. They confirmed it was connected! Everyone on the ship cheered. The recovered cable was then joined to a fresh cable. It was laid to Heart's Content, Newfoundland, where the ship arrived on September 7. Now, there were two working telegraph lines!

Repairing Broken Cables

When cables broke, fixing them was a complex process. First, they measured the electrical resistance of the broken cable. This helped them guess how far away the break was. Then, a repair ship would go to that location. A special grapple would hook the cable and bring it on board. They would test it to see if electricity could flow through it. Buoys were used to mark the ends of the good cable. Finally, the two good ends were joined together.

Communication Speeds

At first, operators sent messages using Morse code. The reception on the 1858 cable was very bad. It took two minutes to send just one character (a letter or number). This was about 0.1 words per minute. Queen Victoria's first message took 67 minutes to send to Newfoundland. But it took 16 hours for the confirmation copy to be sent back to Whitehouse in Ireland.

For the 1866 cable, the way cables were made and messages were sent had greatly improved. The 1866 cable could send 8 words a minute. This was 80 times faster than the 1858 cable! It was not until the 20th century that messages over transatlantic cables reached speeds of 120 words per minute. London became the world center for telecommunications. Eventually, many cables connected Europe and the world.

Later Cables

More cables were laid between Ireland and Newfoundland in 1873, 1874, 1880, and 1894. By the end of the 1800s, British, French, German, and American companies owned cables that linked Europe and North America. This created a complex network of telegraph communication.

The first cables did not have repeaters. Repeaters are devices that make the signal stronger along the line. This would have greatly sped up communication. But there was no way to power them in an undersea cable at the time. The first transatlantic cable with repeaters was TAT-1 in 1956. This was a telephone cable and used different technology.

Impact of the Cables

A study in 2018 found that the transatlantic telegraph greatly increased trade across the Atlantic. It also helped lower prices. The study estimated that the telegraph made trade 8 percent more efficient.it:Cavo sottomarino

See also

In Spanish: Cable telegráfico transatl%C3%A1ntico para ni%C3%B1os

In Spanish: Cable telegráfico transatl%C3%A1ntico para ni%C3%B1os

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |