Samuel Morse facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Morse

|

|

|---|---|

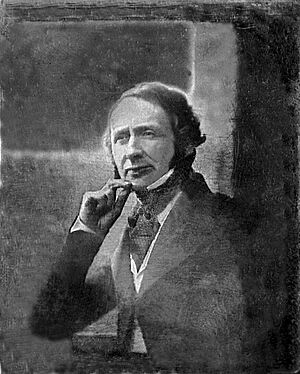

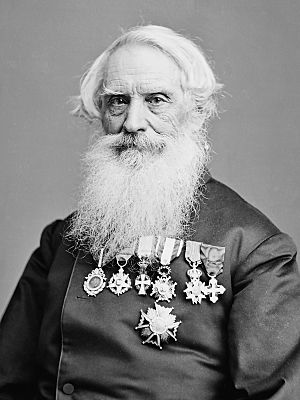

Samuel F. B. Morse, c. 1857

|

|

| Born |

Samuel Finley Breese Morse

April 27, 1791 |

| Died | April 2, 1872 (aged 80) New York City, U.S.

|

| Education | Yale College |

| Occupation | Painter, inventor |

| Known for | The invention and transmission of Morse code |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 7 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Sidney Edwards Morse (brother) |

| Signature | |

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (born April 27, 1791 – died April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and a talented painter. He first became famous as a portrait painter. Later in life, Morse helped invent a single-wire telegraph system. This system was based on earlier European designs. He also helped create Morse code and made the telegraph useful for businesses.

Contents

Samuel Morse's Early Life

Samuel F. B. Morse was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts. He was the first child of Jedidiah Morse, a pastor and geographer, and Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese. His father was a strong believer in education and traditional values.

Samuel went to Phillips Academy and then to Yale College. At Yale, he studied religious ideas, math, and science. He also learned about electricity from professors Benjamin Silliman and Jeremiah Day. To support himself, he painted pictures. In 1810, he graduated from Yale with honors.

Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker on September 29, 1818. She passed away in 1825 after the birth of their third child. Later, he married Sarah Elizabeth Griswold on August 10, 1848. They had four children together.

Morse's Art Career

Morse showed some of his beliefs in his paintings. For example, his painting Landing of the Pilgrims showed people in simple clothes. This painting caught the eye of a famous artist named Washington Allston. Allston invited Morse to go to England to study painting.

Morse sailed to England in 1811. There, he improved his painting skills with Allston's help. He was accepted into the Royal Academy. He loved the art of the Renaissance, especially the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. Morse created his own masterpiece called Dying Hercules.

Some people thought Dying Hercules was a political statement. It seemed to show the strength of the young United States against Britain. At this time, America and Britain were fighting in the War of 1812.

After his studies, Morse returned to the United States in 1815. He began his full-time career as a painter.

Capturing American Life

From 1815 to 1825, Morse's painting skills grew a lot. He wanted to show the spirit of American culture. He painted portraits of important figures like former President John Adams in 1816. He also painted leaders involved in the famous Dartmouth College case.

Morse also found work painting for wealthy people in Charleston, South Carolina. His 1818 painting of Mrs. Emma Quash showed the rich lifestyle of Charleston. However, a financial crisis in 1819 caused fewer people to ask for paintings.

In 1820, Morse was asked to paint President James Monroe. He also painted The House of Representatives in 1821. This painting showed American democracy in action. He traveled to Washington D.C. to draw the new Capitol building. He included eighty people in the painting. Morse chose to show a night scene, using lamplight to highlight the work. He wanted to show that Congress's dedication to democracy never stopped.

The House of Representatives was shown in New York City in 1823. However, it did not attract many visitors. People might have felt that the building in the painting was more important than the people.

Morse was also honored to paint the Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette was a French hero who helped America during the American Revolution. Morse wanted to paint a grand portrait of him. He showed Lafayette against a beautiful sunset. The painting also included busts of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington. A peaceful forest in the background showed America's calm and success.

In 1826, Morse helped start the National Academy of Design in New York City. He was the president of the academy for many years.

From 1830 to 1832, Morse traveled in Europe to improve his painting. He visited Italy, Switzerland, and France. In Paris, he became friends with the writer James Fenimore Cooper. He painted miniature copies of 38 famous paintings from the Louvre museum onto one large canvas. He called this work The Gallery of the Louvre.

In 1832, Morse became a professor of painting and sculpture at the University of the City of New York, now New York University.

In 1839, Morse met Louis Daguerre in Paris. Daguerre had invented the daguerreotype, which was the first practical way to take photographs. Morse was very interested. He wrote a letter describing the invention, which was printed in many American newspapers. This helped people learn about photography. Mathew Brady, a famous early American photographer, studied with Morse. Brady later took many pictures of Morse.

Some of Morse's paintings and sculptures can be seen at his Locust Grove estate in Poughkeepsie, New York.

The Telegraph Invention

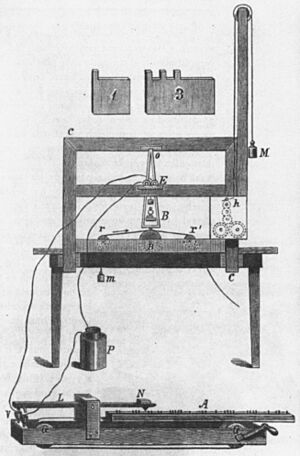

In 1832, while returning from Europe by ship, Morse met Charles Thomas Jackson. Jackson knew a lot about electromagnetism. After seeing Jackson's experiments, Morse thought of a single-wire telegraph system. He put his painting, The Gallery of the Louvre, aside to work on this idea. The first Morse telegraph, used for his patent application, is now at the National Museum of American History. Over time, the Morse code he created became the main language for telegraphs worldwide.

Other inventors were also working on telegraphs. In England, William Cooke and Professor Charles Wheatstone learned about an electromagnetic telegraph from 1833. They were able to launch a commercial telegraph system before Morse. Cooke became interested in electrical telegraphy in 1836. With more money, he built a small electrical telegraph in three weeks. Wheatstone also experimented with telegraphy. He realized that many small batteries worked better than one large one for sending signals over long distances. Cooke and Wheatstone patented their electrical telegraph in May 1837. Soon, they had a 13-mile (21 km) telegraph line for the Great Western Railway. However, Morse's cheaper method would later become more popular.

Making Signals Travel Far

Morse faced a problem: his telegraph signal could only travel a few hundred yards. His big breakthrough came from Professor Leonard Gale, a chemistry teacher at New York University. With Gale's help, Morse added extra circuits, called relays, at regular points. This allowed him to send a message through ten miles (16 km) of wire. This was the important discovery he needed. Morse and Gale were soon joined by Alfred Vail, a skilled young man who also had money to invest.

On January 11, 1838, Morse and Vail showed the electric telegraph to the public for the first time. This happened at the Speedwell Ironworks in Morristown, New Jersey. The telegraph could send messages up to two miles (3.2 km). The first public message sent was, "A patient waiter is no loser."

Morse went to Washington, D.C. in 1838 to ask the government for money to build a telegraph line, but he was not successful. He then went to Europe, but found that Cooke and Wheatstone already had patents there. After returning to the U.S., Morse finally got financial help from a congressman named Francis Ormand Jonathan Smith. This might have been the first time the government supported a private researcher for practical inventions.

Government Support and Success

Morse made his last trip to Washington, D.C., in December 1842. He set up wires between two rooms in the Capitol building. He sent messages back and forth to show how his telegraph worked. In 1843, Congress gave him $30,000 to build an experimental 38-mile (61 km) telegraph line. This line would connect Washington, D.C., and Baltimore.

On May 1, 1844, there was an impressive demonstration. News of the Whig Party's choice for president, Henry Clay, was telegraphed from Baltimore to the Capitol in Washington.

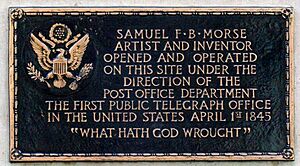

On May 24, 1844, the line officially opened. Morse sent the famous words, "What hath God wrought," from the Supreme Court chamber in Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. Annie Ellsworth chose these words from the Bible. Her father, Henry Leavitt Ellsworth, had supported Morse's invention and helped get the funding. Morse's telegraph could send thirty characters per minute.

In May 1845, the Magnetic Telegraph Company was formed. Its goal was to build telegraph lines from New York City to other major cities. Telegraph lines quickly spread across the United States. By 1850, 12,000 miles of wire had been laid.

Telegraph Patent and Recognition

Morse received a patent for the telegraph in 1847. This patent was given by Sultan Abdülmecid in Istanbul, Turkey. The Sultan even tested the new invention himself.

In the United States, Morse held his telegraph patent for many years. However, people often ignored it or challenged it in court. In 1853, a case called The Telegraph Patent case – O'Reilly v. Morse went to the U.S. Supreme Court. After a long investigation, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney decided that Morse was the first to combine the battery, electromagnetism, the electromagnet, and the right battery setup to make a working telegraph.

The Supreme Court did not agree with all of Morse's claims. However, they did agree that Morse could patent his "repeater" system. This system used a series of relays and batteries. Each relay would close a circuit, causing the next battery to power the next relay. This allowed Morse's signal to travel long distances without getting weaker. This was a very important invention because it meant messages could be sent across vast areas.

International Recognition

With help from the American ambassador in Paris, European governments were asked to recognize Morse's contributions. Many countries were using his invention but had not honored him. In 1858, Morse was given 400,000 French francs (about $80,000 at the time). This money came from the governments of France, Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, Piedmont, Russia, Sweden, Tuscany, and the Ottoman Empire. Each country contributed based on how many Morse telegraphs they used.

In 1851, the Morse telegraph system was officially chosen as the standard for European telegraphy. Only the United Kingdom continued to use a different type of telegraph.

In 1858, Morse brought wired communication to Latin America. He set up a telegraph system in Puerto Rico, which was a Spanish colony then. Morse's oldest daughter, Susan, often visited her uncle in Guayama. She met Edward Lind, a Danish merchant, and they later married. Morse often spent winters at their home in Arroyo. He set up a two-mile telegraph line connecting his son-in-law's farm to their house. The line opened on March 1, 1859.

Later Years and Legacy

Morse supported Cyrus West Field's big plan to build the first telegraph line across the ocean. Morse had experimented with underwater telegraph circuits since 1842. He invested $10,000 in Field's Atlantic Telegraph Company and became an honorary "Electrician." The first two attempts to lay the cable failed. The third attempt succeeded in 1858, and the first transatlantic telegraph messages were sent. However, this cable only worked for three months. A more durable cable was laid in 1866, starting the era of reliable transatlantic telegraph service.

Besides the telegraph, Morse also invented a machine that could carve three-dimensional sculptures from marble or stone. However, he could not patent it because a similar design already existed.

Samuel Morse gave a lot of money to charity. He was also interested in how science and religion connected. He provided money to create lectures on "the relation of the Bible to the Sciences." Even though he did not always get paid for later uses of his inventions, he lived a comfortable life.

He passed away in New York City on April 2, 1872. He was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. At the time of his death, his estate was worth about $500,000.

Honors and Awards

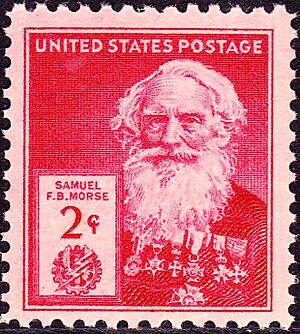

Morse received many honors and financial awards from other countries. However, he did not get much recognition in the U.S. until near the end of his life. On June 10, 1871, a bronze statue of Samuel Morse was revealed in Central Park, New York City. His picture also appeared on the back of the United States two-dollar bill silver certificate in 1896.

A blue plaque was placed at 141 Cleveland Street, London, where he lived from 1812 to 1815.

Morse received many awards from different countries:

- The Atiq Nishan-i-Iftikhar from Sultan Abdülmecid of Turkey (around 1847).

- A "golden snuff box" with the Prussian gold medal for science from the King of Prussia (1851).

- The Great Gold Medal of Arts and Sciences from the King of Württemberg (1852).

- The Great Golden Medal of Science and Arts from Emperor of Austria (1855).

- A cross of Chevalier in the Légion d'honneur from the Emperor of France.

- The Cross of a Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog from the King of Denmark (1856).

- The Cross of Knight Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic from the Queen of Spain.

- The Order of the Tower and Sword from Portugal (1860).

- The insignia of chevalier of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus from Italy (1864).

In 1975, Morse was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

On April 1, 2012, Google released "Gmail Tap," an April Fools' Day joke. It allowed users to send text messages using Morse Code. This joke later became a real product.

Patents

- US Patent 1,647, Improvement in the mode of communicating information by signals by the application of electro-magnetism, June 20, 1840

- US Patent 1,647 (Reissue #79), Improvement in the mode of communicating information by signals by the application of electro-magnetism, January 15, 1846

- US Patent 1,647 (Reissue #117), Improvement in electro-magnetic telegraphs, June 13, 1848

- US Patent 3,316, Method of introducing wire into metallic pipes, October 5, 1843

- US Patent 4,453, Improvement in Electro-magnetic telegraphs, April 11, 1846

- US Patent 4,453 (Reissue #118), Improvement in Electro-magnetic telegraphs, June 13, 1848

- US Patent 6,420, Improvement in electric telegraphs, May 1, 1849

Images for kids

-

Portrait of John Adams

-

The Gallery of the Louvre 1831–33

-

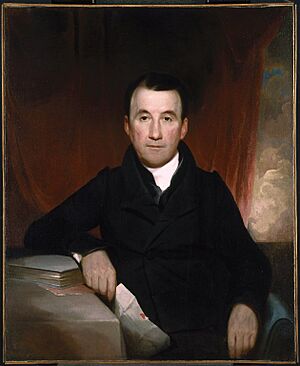

Portrait of James Monroe, 5th President of the United States (c. 1819)

-

Eli Whitney, inventor, 1822. Yale University Art Gallery

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Morse para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Morse para niños

- Daniel Davis Jr.

- Seconds pendulum

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |