Morse code facts for kids

Morse code is a special way to send messages using sounds, lights, or electrical signals. It turns letters and numbers into short and long signals, called dots and dashes. Imagine a secret language where every letter has its own pattern of beeps!

This code is named after Samuel Morse, who helped create the first electric telegraph. An engineer named Alfred Vail improved Morse's first ideas. Later, Friedrich Clemens Gerke made it even simpler, leading to the international version we know today.

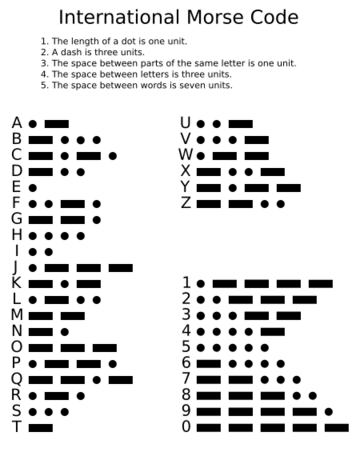

International Morse code uses 26 basic letters (A to Z), numbers (0 to 9), and some punctuation marks. There are no capital or small letters in Morse code. Each letter or number is a unique sequence of dots and dashes. A dash is three times longer than a dot. After each dot or dash, there's a short silence. Letters in a word are separated by a slightly longer silence, and words are separated by an even longer silence.

People who know Morse code can understand these patterns just by hearing them or seeing them flash. It's like listening to a song! Morse code is often sent by turning an electric current, radio waves, or a light on and off.

To make sending messages faster, the most common letters in English, like 'E', have the shortest codes. This makes the code very efficient. The speed of Morse code is measured in "words per minute."

Contents

The Story of Morse Code

Early Ways to Send Messages

Long ago, in the early 1800s, people in Europe started experimenting with sending messages using electricity. These early ideas helped create the first telegraph systems.

After Hans Christian Ørsted discovered electromagnetism in 1820, and William Sturgeon invented the electromagnet in 1824, new ways to send messages over long distances quickly developed. Electric pulses traveled along wires to a receiving machine. Some early telegraphs used a single needle that moved left or right to show parts of a message. This was slow because operators had to watch the needle and write down each part.

In Britain, William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone created an electric telegraph in 1837. It was the first commercial telegraph and was used on a railway line.

Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail's Invention

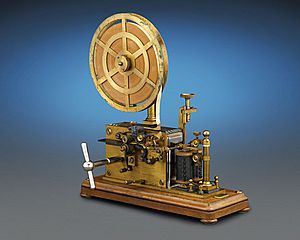

The American artist Samuel Morse, with help from Joseph Henry and Alfred Vail, developed an electric telegraph system. They needed a simple way to send language using just electrical pulses and silences. Around 1837, Morse came up with an early version of the code.

Morse's first telegraph machine made marks on a paper tape. When electricity flowed, a stylus pressed onto the tape, making an indentation. When the electricity stopped, the stylus lifted. At first, Morse only planned to send numbers and use a codebook to look up words. But in 1840, Alfred Vail expanded the code to include letters and special characters. Vail even counted the letters in a local newspaper to see which ones were used most often. The most common letters got the shortest codes. This code, first used in 1844, became known as American Morse code.

From Clicks to Sounds

Operators soon realized they could understand the clicks made by the telegraph machine without needing the paper tape. They learned to translate the clicks directly into dots and dashes by ear. When Morse code was used for radio communication, dots and dashes became short and long beeps.

Operators started calling dots "dits" and dashes "dahs" because that's how they sounded. If a dot wasn't the last part of a letter, they'd say "di." For example, the letter 'L' (dot-dash-dot-dot) was spoken as "di-dah-di-dit."

Gerke's Improvements for Everyone

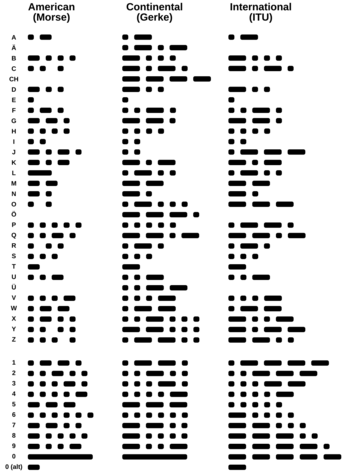

The Morse code we use today, called International Morse Code, came from improvements made by Friedrich Gerke in 1848. His version was known as the "Hamburg alphabet." Gerke changed many codes and removed the different dash lengths and spaces that were in American Morse. He made it simpler, using only dots and dashes.

Gerke's code was adopted in Germany and Austria in 1851. This led to the International Morse code being standardized in 1865. Most of Gerke's codes were kept, with a few changes for other letters and all the numbers. Only a few letters, like 'E', 'H', 'K', and 'N', kept their original Morse codes.

Morse Code in the Air and at Sea

In the 1890s, Morse code became very important for early radio communication, before people could send voices over the radio. For many years, most international messages sent over telegraph lines, undersea cables, and radio used Morse code.

During World War I, airships and military planes used radio telegraphy. By the mid-1920s, Morse code was regularly used in aviation. For example, in 1928, when the Southern Cross made the first airplane flight from California to Australia, a radio operator on board used Morse code to talk to ground stations.

From the 1930s, pilots needed to know Morse code. They used it for early communication systems and to identify navigation beacons. These beacons sent out short Morse code signals to tell pilots where they were.

Morse code was also vital during World War II. Warships used it to send secret, encrypted messages to naval bases. Long-range patrol planes used it to scout for enemy ships.

Morse code was the international standard for sending SOS distress signals at sea until 1999. On January 31, 1997, the French Navy sent its final Morse code message: "Calling all. This is our last call before our eternal silence."

The End of Commercial Morse Code

In the United States, the last commercial Morse code message was sent on July 12, 1999. It signed off with Samuel Morse's original 1844 message: WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT.

Even today, the United States Air Force still trains a small number of people in Morse code. The United States Coast Guard no longer uses Morse code on the radio, but some amateur radio enthusiasts keep old Morse stations active.

Becoming a Morse Code Expert

The speed of Morse code is measured in words per minute (WPM). Because letters and words have different lengths in dots and dashes, a standard word like PARIS or CODEX is used to measure speed.

Very skilled operators can understand Morse code at speeds over 40 WPM. Some have even reached over 100 WPM! At these speeds, they are "hearing" whole phrases, not just individual letters.

There are still contests for copying Morse code. In 1939, Theodore Roosevelt McElroy set a record by copying 75.2 WPM.

Today, many amateur radio groups recognize high-speed Morse code skills. The American Radio Relay League offers certificates for copying code at speeds from 10 WPM up to 40 WPM. Even Boy Scouts of America can earn a Morse interpreter's strip for translating code at 5 WPM.

For many years, you needed to pass a Morse code test to get an amateur radio license in the U.S. However, since February 23, 2007, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) no longer requires Morse code for amateur radio licenses.

Morse Code Around the World

Morse Code in Aviation

Pilots use radio navigation aids to help them fly. These stations send out identification letters in Morse code so pilots can make sure they are using the correct station. For example, a station might send "UCL" in Morse code.

During maintenance, a station might send the signal TEST or stop sending its identification. This tells pilots not to use that station. In Canada, the identification is removed completely if the navigation aid should not be used.

In aviation, Morse code is usually sent very slowly, about 5 words per minute. Pilots don't always need to know Morse code by heart because the dot/dash sequence is often written next to the station's symbol on their maps. Some modern navigation systems can even translate the code into letters for them.

Amateur Radio Fun

International Morse code is very popular among amateur radio operators, often called "hams." They use it for a type of communication called "continuous wave" or "CW."

Early amateur radio operators used Morse code all the time because voice radio transmitters were not common until the 1920s. Morse code is great for long-distance communication because it uses less radio bandwidth than voice. This means it can cut through noise and interference better, making it easier to hear weak signals from far away.

Amateur radio operators use many abbreviations to speed up Morse code conversations. For example, CQ means "seek you" (I want to talk to anyone who can hear me). OM means "old man," and YL means "young lady." These abbreviations help people communicate even if they speak different languages.

While some hams still use traditional telegraph keys, many use electronic devices called "keyers" or computer software to send and decode Morse code.

Other Uses for Morse Code

Warships, like those in the U.S. Navy, still use signal lamps to send messages in Morse code. This allows them to communicate without using radio, which helps them stay hidden.

Some amateur radio repeaters, which are used for voice communication, also identify themselves using Morse code.

Sending an SOS

One of the most important uses of Morse code is sending the SOS distress signal: ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ . This signal is not sent as three separate letters, but as one continuous pattern. It means "This is an emergency message, everyone else be quiet!" You can send SOS in many ways, like flashing a light, beeping a horn, or even pulling on a rope.

Morse Code as a Helping Hand

Morse code has also been used as an assistive technology to help people with disabilities communicate. For example, some Android phones let users type using Morse code instead of a keyboard.

People with severe movement difficulties can use Morse code if they have even a little bit of control. They might use a "sip-and-puff" device, where they blow or suck on a tube to make dots and dashes. Once learned, Morse code can be faster than other communication methods and doesn't always require looking at a screen.

There are stories of people using Morse code in amazing ways. In 1966, a prisoner of war named Jeremiah Denton blinked the word TORTURE in Morse code during a TV interview, letting the world know what was happening.

How Morse Code Signals Work

International Morse code uses five main parts:

- A short mark, called a dot or dit: This is one unit of time.

- A long mark, called a dash or dah: This is three units of time.

- A tiny silence between dots and dashes within a letter: This is one unit of time.

- A short silence between letters: This is three units of time.

- A medium silence between words: This is seven units of time.

Sending Messages

Morse code can be sent in many ways. It started as electrical pulses on a wire. Later, it was sent as audio tones, radio signals, or even flashing lights using devices like an Aldis lamp or a flashlight. Some mine rescues have used rope pulls: a short pull for a dot, a long pull for a dash.

Messages are usually sent by hand using a telegraph key. The skill of the sender can affect how clear the message is. Experienced operators can send and receive messages very quickly. Each operator has a unique style, called their "fist." A "good fist" means the code is clear and easy to understand.

Timing the Signals

Here's how the word MORSE CODE would look with exact timing, where ▓˽

-

M O R S E C O D E ▓▓▓˽▓▓▓ ˽˽˽ ▓▓▓˽▓▓▓˽▓▓▓ ˽˽˽ ▓˽▓▓▓˽▓ ˽˽˽ ▓˽▓˽▓ ˽˽˽ ▓ ˽˽˽˽˽˽˽ ▓▓▓˽▓˽▓▓▓˽▓ ˽˽˽ ▓▓▓˽▓▓▓˽▓▓▓ ˽˽˽ ▓▓▓˽▓˽▓ ˽˽˽ ▓ ↑ ↑↑↑↑ symbol dahditletterword space spacespace

Saying Morse Code Sounds

When people talk about Morse code, they often say "dah" for dashes, "dit" for dots at the end of a letter, and "di" for dots inside a letter. So, the word MORSE CODE would be spoken like this:

-

dah dah dah dah dah di dah dit di di dit dit dah di dah dit dah dah dah dah di dit dit M O R S E C O D E

When learning Morse code for radio, it's best to learn the actual sounds of each letter and symbol, not just how they look written down.

Farnsworth Speed for Learning

When learning Morse code, sometimes two different speeds are used: a character speed and a text speed. The character speed is how fast each letter is sent. The text speed is how fast the whole message is sent. For example, individual letters might be sent quickly, but the pauses between letters and words are made longer. This "Farnsworth method" helps learners recognize the sound of each character before speeding up the whole message.

Learning Morse Code

There are a few popular ways to learn Morse code. The Farnsworth method teaches you to send and receive letters at their full speed, but with longer pauses between characters and words. This gives you more time to think and recognize the unique "sound shape" of each letter. As you get better, the pauses become shorter.

Another method is the Koch method. It starts with the full target speed right away but begins with only two characters. Once you can copy those two characters with high accuracy, another character is added, and so on, until you know all of them.

Many people have learned Morse code by listening to practice broadcasts from stations like W1AW, the headquarters of the American Radio Relay League.

Memory Tricks (Mnemonics)

People have created memory tricks, called mnemonics, to help learn Morse code. These often use words or phrases that have the same rhythm as a Morse character. For example, the Morse code for Q (dah-dah-di-dah) can be remembered with the phrase "God Save the Queen." The Morse for F (di-di-dah-dit) can be remembered as "Did she like it?"

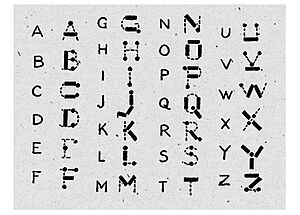

Letters, Numbers, and Punctuation

Here are the International Morse codes for common letters, numbers, and some punctuation.

| Category | Character | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Letters | A, a | ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | B, b | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Letters | C, c | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Letters | D, d | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Letters | E, e | ▄ |

| Letters | F, f | ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Letters | G, g | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Letters | H, h | ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Letters | I, i | ▄ ▄ |

| Letters | J, j | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | K, k (Also a signal for "invite to transmit") |

▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | L, l | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Letters | M, m | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | N, n | ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Letters | O, o | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | P, p | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Letters | Q, q | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | R, r | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Letters | S, s | ▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Letters | T, t | ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | U, u | ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | V, v | ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | W, w | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | X, x | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | Y, y | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Letters | Z, z | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Numbers | 0 | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Numbers | 1 | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Numbers | 2 | ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Numbers | 3 | ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Numbers | 4 | ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Numbers | 5 | ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Numbers | 6 | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Numbers | 7 | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Numbers | 8 | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Numbers | 9 | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Punctuation | Period [ . ] | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Punctuation | Comma [ , ] | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Punctuation | Question mark [ ? ] | ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Punctuation | Slash [ / ] | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Punctuation | Open parenthesis [ ( ] | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Punctuation | Close parenthesis [ ) ] | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Punctuation | Equal sign [ = ] (Also a signal for "new section") |

▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Punctuation | Hyphen or Minus sign [ - ] | ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Punctuation | Quotation mark [ " ] | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Punctuation | At sign [ @ ] | ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ |

| Other Letters | Ñ, ñ | ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Prosigns | End of work ( SK ) |

▄ ▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄▄▄ |

| Prosigns | Error ( HH ) |

▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ |

| Prosigns | Wait ( AS ) |

▄ ▄▄▄ ▄ ▄ ▄ |

Special Signals (Prosigns)

Prosigns are special Morse code signals that tell you something about the message itself, like when a message starts or ends. For example, the signal for 'K' (dash-dot-dash) can also mean "I invite you to transmit" or "over." The signal for '=' (dash-dot-dot-dot-dash) can mean "new section" or "new paragraph."

Other Languages and Symbols

Many languages have their own Morse codes for letters not found in the basic Latin alphabet. For example, the Spanish letter Ñ has its own unique Morse code. Other languages like Greek, Russian, and Ukrainian also have Morse codes that match their alphabets.

In 2004, the @ symbol was officially added to International Morse code. This made it easier to send email addresses using Morse code.

Decoding Morse Code with Computers

Today, there's software that can help decode Morse code. Some radio receivers can automatically translate Morse signals into text. There are even smartphone apps that can help you learn and decode Morse code!

See also

In Spanish: Código morse para niños

In Spanish: Código morse para niños

- Alfred Vail

- Amateur radio

- Guglielmo Marconi

- Morse code abbreviations

- Morse code mnemonics

- NATO phonetic alphabet

- Telegraph key

- Wireless telegraphy

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |