Joseph Henry facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joseph Henry

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 1st Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution | |

| In office 1846–1878 |

|

| Succeeded by | Spencer Fullerton Baird |

| 2nd President of the National Academy of Sciences | |

| In office 1868–1879 |

|

| Preceded by | Alexander Dallas Bache |

| Succeeded by | William Barton Rogers |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 17, 1797 Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Died | May 13, 1878 (aged 80) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse | Harriet Henry (née Alexander) |

| Children | William Alexander (1832–1862) Mary Anna (1834–1903) Helen Louisa (1836–1912) Caroline (1839–1920) |

| Alma mater | The Albany Academy |

| Known for | Electromagnetic induction, Inventor of a precursor to the electric doorbell and electric relay |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | The Albany Academy The College of New Jersey Smithsonian Institution Columbian College |

Joseph Henry (December 17, 1797 – May 13, 1878) was an amazing American scientist. He was the very first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, a famous museum and research center. People really looked up to him during his life.

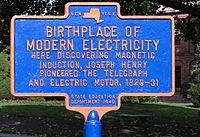

Henry made big discoveries while working with electromagnets. He found out about a special electric effect called self-inductance. He also discovered mutual inductance, which Michael Faraday found around the same time. Faraday published his findings first. Henry also made the electromagnet a useful tool. He even invented an early version of the electric doorbell in 1831 and the electric relay in 1835. The unit for inductance, called the Henry, is named after him! His work on the electric relay was super important for inventing the electrical telegraph, which was later developed by Samuel F. B. Morse and Sir Charles Wheatstone.

Contents

Biography of Joseph Henry

Early Life and Education

Joseph Henry was born in Albany, New York. His parents, Ann Alexander Henry and William Henry, were immigrants from Scotland. His family was not wealthy, and his father passed away when Joseph was young. He then lived with his grandmother in Galway (village), New York. He went to a school that was later named "Joseph Henry Elementary School" in his honor.

After school, he worked in a general store. By age thirteen, he became an apprentice watchmaker and silversmith. Joseph first loved theater and almost became an actor! But his interest in science began at age sixteen. He read a book called Popular Lectures on Experimental Philosophy, which was full of scientific ideas.

In 1819, he started at The Albany Academy. He got free tuition there, but he was still so poor that he had to teach and tutor others to support himself. He first planned to study medicine. However, in 1824, he became an assistant engineer for a road survey between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. This experience inspired him to pursue a career in civil or mechanical engineering.

Discoveries in Electromagnetism

Joseph Henry was excellent at his studies. He often helped his teachers with science lessons! In 1826, he became a Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy at The Albany Academy. Many of his most important discoveries happened during this time.

He was curious about Earth's magnetism. This led him to experiment with magnetism in general. He was the first to tightly coil insulated wire around an iron core. This made a much more powerful electromagnet than earlier designs. Using this method, he built the strongest electromagnet of his time for Yale.

He also showed how to make electromagnets work best. If you use two electrodes with one battery, it's best to wind many coils of wire side-by-side. But if you use multiple batteries, one long coil works best. This last idea was key to making the telegraph possible! Some historians think Henry made discoveries before Faraday and Hertz. However, Henry didn't publish his work, so he isn't officially credited.

In 1831, Henry used his new electromagnetic ideas to create one of the first machines that used electromagnetism for motion. This was an early version of a modern DC motor. It didn't spin, but it was an electromagnet rocking back and forth on a pole. This rocking motion happened as the magnet's leads touched different parts of the battery, changing its magnetic direction.

This machine helped Henry understand self inductance. British scientist Michael Faraday also discovered this property around the same time. Since Faraday published his findings first, he is officially known as the discoverer.

Work at Princeton University

From 1832 to 1846, Henry was the first Chair of Natural History at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). He taught many subjects, including natural history, chemistry, and architecture. He also ran a laboratory on campus. Years later, Henry wrote that he did "several thousand original investigations on electricity, magnetism, and electro-magnetism" at Princeton.

Henry had a very important research assistant named Sam Parker. Parker was an African American man hired by Princeton to help Henry. In a letter from 1841, Henry wrote that Parker was "indispensable" and helped him with all the "dirty work of the laboratory." Parker provided materials, fixed equipment, and was crucial to Henry's experiments. When Parker became ill in 1842, Henry's experiments stopped until he recovered. This shows how important Parker was to his work.

Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

Joseph Henry became the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1846. He held this important position until 1878. In 1848, he worked with Professor Stephen Alexander to study the temperatures of different parts of the sun. They used a special tool called a thermopile to find that sunspots were cooler than the areas around them.

During the American Civil War (1861-1862), Henry arranged for famous speakers to give lectures at the Smithsonian. These speakers included important figures like Wendell Phillips, Horace Greeley, Henry Ward Beecher, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. However, Henry made a decision not to allow the famous orator and former enslaved person, Frederick Douglass, to speak at the Smithsonian.

In 2014, a book called The Civil War Out My Window: Diary of Mary Henry was released. It shared the diary of Henry's daughter, Mary, from 1855 to 1878. Her diary often mentioned her father, showing how much she cared for him.

Aeronautics and the Civil War

Professor Henry met Professor Thaddeus Lowe, a balloonist. Lowe was interested in lighter-than-air gases and weather, especially the high winds we now call the Jet stream. Lowe wanted to cross the Atlantic Ocean in a huge gas balloon. Henry was very interested in Lowe's plans and helped him connect with important scientists.

In June 1860, Lowe successfully tested his giant balloon, first called the City of New York and later The Great Western. He flew from Philadelphia to Medford, New York. Lowe couldn't try his transatlantic flight until 1861. So, Henry convinced him to fly his balloon west and then back east. This would keep his investors interested.

In March 1861, Lowe took smaller balloons to Cincinnati, Ohio. On April 19, he launched a flight that landed him in Confederate South Carolina. With the Southern States leaving the Union and the American Civil War starting, Lowe stopped his transatlantic plans. With Henry's support, Lowe went to Washington, D.C. He offered his skills as an aeronaut to the U.S. government. Henry wrote a letter to the Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, supporting Lowe.

Henry's letter explained that Lowe's balloon could:

- Stay inflated for several days.

- Be moved easily by a few people on calm days.

- Rise high enough to see twenty miles around, even at night to spot enemy camps.

- Send telegrams easily between the balloon and the commanding officer.

- Potentially float over enemy camps and return by rising to higher winds.

Henry was sure that Lowe's balloon could provide important information about the land and enemy movements. He also noted that while inflating the balloon far from a city would need special equipment, the results would be worth it.

Based on Henry's recommendation, Lowe went on to create the Union Army Balloon Corps. He served for two years with the Army of the Potomac as a Civil War "Aeronaut."

Later Years and Legacy

As a famous scientist and the head of the Smithsonian, Joseph Henry often had other scientists and inventors visit him for advice. He was known for being patient, kind, and having a gentle sense of humor.

One visitor was Alexander Graham Bell, who came to Henry on March 1, 1875. Henry was interested in Bell's experimental devices. Bell returned the next day to show them. Bell then told Henry about his idea to send human speech electrically using a "harp apparatus." Henry told Bell that he had "the germ of a great invention." Henry advised Bell not to publish his ideas until he had perfected the invention. When Bell said he didn't have enough knowledge, Henry firmly told him: "Get it!"

On June 25, 1876, Bell's experimental telephone was shown at an exhibition in Philadelphia. Henry was one of the judges for the electrical exhibits. On January 13, 1877, Bell showed his instruments to Henry again at the Smithsonian. Henry then invited Bell to show them that night at the Washington Philosophical Society. Henry praised "the value and astonishing character of Mr. Bell's discovery and invention."

Joseph Henry passed away on May 13, 1878. He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C. The famous composer John Philip Sousa wrote the Transit of Venus March for the unveiling of Joseph Henry's statue in front of the Smithsonian Castle.

Honors and Memorials

Henry was a member of the United States Lighthouse Board from 1852 until his death. He became chairman in 1871 and was the only civilian to hold that position. The United States Coast Guard honored Henry for his work on lighthouses and fog signals. They named a ship after him, the Joseph Henry, launched in 1880.

In 1915, Henry was added to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in Bronx, New York.

Bronze statues of Henry and Isaac Newton represent science at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.. They are two of 16 historical figures shown in the main reading room.

In 1872, John Wesley Powell named a mountain range in southeastern Utah after Henry. The Henry Mountains were the last mountain range to be added to the map of the 48 connected U.S. states.

At Princeton, the Joseph Henry Laboratories and the Joseph Henry House are named for him.

After The Albany Academy moved in the 1930s, its old building was renamed Joseph Henry Memorial. There is a statue of him outside. It is now the main office for the Albany City School District.

Key Milestones

- 1826: Became Professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at The Albany Academy, New York.

- 1832: Became Chair of Natural History at Princeton University (then the College of New Jersey) until 1846.

- 1835: Invented the electromechanical relay.

- 1846: Became the first secretary of the Smithsonian Institution until 1878.

- 1848: Edited Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, the Smithsonian's first publication.

- 1852: Appointed to the Lighthouse Board.

- 1871: Appointed chairman of the Lighthouse Board.

Other Recognitions

- Elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1835.

- Elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1851.

- A school in Washington, D.C., built in 1878–80, was named the Joseph Henry School.

- The Henry Mountains in Utah were named in his honor by geologist Almon Harris Thompson.

- Mount Henry in California is also named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Henry para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Henry para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |