Wendell Phillips facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wendell Phillips

|

|

|---|---|

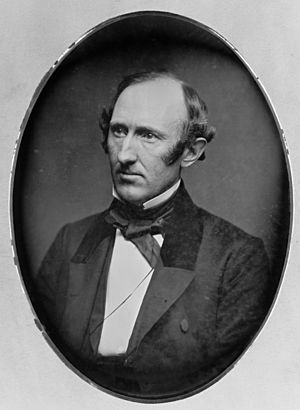

A daguerrotype by Mathew Brady of Wendell Phillips in his forties

|

|

| Born | November 29, 1811 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | February 2, 1884 (aged 72) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Burial place | Milton Cemetery |

| Education | Harvard University (AB, LLB) |

| Occupation | Attorney |

| Known for | Abolitionism, advocacy for Native Americans |

| Parent(s) | Sarah Walley John Phillips |

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an important American leader. He fought to end slavery. He also spoke up for Native Americans. Phillips was a great speaker and a lawyer.

Many Black Americans saw him as a white person who truly treated everyone equally. They believed he had no prejudice based on race. Some even thought he was more important than other abolitionist leaders like William Lloyd Garrison. From 1850 to 1865, he was a top figure in the movement to end slavery.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Wendell Phillips was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on November 29, 1811. His parents were Sarah Walley and John Phillips. His father was a rich lawyer and the first mayor of Boston.

Wendell went to Boston Latin School. He then graduated from Harvard College in 1831. He continued his studies at Harvard Law School, finishing in 1833. In 1834, Phillips became a lawyer in Massachusetts. He opened his own law office in Boston that same year.

His speaking teacher, Edward T. Channing, taught him to speak clearly and simply. Phillips really took this lesson to heart.

Marriage to Ann Terry Greene

In 1836, Phillips was starting to support the fight against slavery. That's when he met Ann Greene. Ann believed that this cause needed full dedication, not just support.

They got engaged that year. Ann said Wendell was her "best three quarters." They were married for 46 years, until Wendell passed away.

Fighting to End Slavery

After meeting William Lloyd Garrison in 1836, Phillips became a strong supporter of ending slavery. He stopped working as a lawyer to focus completely on the movement. Phillips joined the American Anti-Slavery Society. He often gave speeches at their meetings.

People admired his speaking skills so much that they called him "abolition's golden trumpet." Like many others fighting slavery, he avoided buying goods made by enslaved people. This included cane sugar and cotton clothing. He was also part of the Boston Vigilance Committee. This group helped enslaved people who had escaped avoid being caught.

Phillips believed that unfair treatment based on race caused many problems in society. He, like Garrison, criticized the Constitution. They felt it allowed slavery to continue. He thought the country would be better off if the states with slavery were allowed to leave. This way, the rest of the country wouldn't be part of the problem.

On December 8, 1837, Phillips gave a powerful speech in Boston. This speech showed his strong leadership in the anti-slavery movement. His inspiring words led to a close partnership with Garrison. This partnership helped define the abolitionist movement in the 1840s.

Trip to Europe

In 1839, Wendell and Ann traveled to Europe for two years. They spent summers in Great Britain and the rest of the year in mainland Europe. They met important people, including other abolitionists.

In 1840, they went to London for the World Anti-Slavery Convention. Other American delegates were there too. Ann and several other women were delegates. However, the organizers did not expect female delegates. They were not allowed to join the main meeting.

Ann told Phillips not to "shilly-shally," meaning not to hesitate. So, Phillips spoke up for the women. He argued that the invitation was for "friends of the slave" from all nations. He said that in Massachusetts, women were treated equally in anti-slavery groups.

When the call reached America we found that it was an invitation to the friends of the slave of every nation and of every clime. Massachusetts has for several years acted on the principal of admitting women to an equal seat with men, in the deliberative bodies of the anti-slavery societies.... We stand here in consequence of your invitation, and knowing our custom, as it must be presumed you did, we had a right to interpret 'friends of the slave' to include women as well as men.

Phillips and others tried their best. The women were allowed to attend but had to sit separately. They were not allowed to speak. This event is often seen as the start of the women's rights movement.

Before the Civil War

In 1854, Phillips was involved in trying to help Anthony Burns. Burns was an enslaved person who had escaped but was caught in Boston. Phillips was charged for his part in trying to free Burns from jail.

After John Brown was executed in December 1859, Phillips spoke at his funeral. This was at the John Brown Farm State Historic Site in New York. Phillips wanted Brown to be buried in a famous cemetery. He thought this would help the fight against slavery. He gave a powerful speech at the funeral.

At the start of the Civil War, Phillips gave a speech. He first defended the Southern states' right to leave the Union. He said:

A large body of people, sufficient to make a nation, have come to the conclusion that they will have a government of a certain form. Who denies them the right? Standing with the principles of '76 behind us, who can deny them the right? ...I maintain on the principles of '76 that Abraham Lincoln has no right to a soldier in Fort Sumter. ...You can never make such a war popular. ...The North never will endorse such a war."

In 1860 and 1861, many abolitionists were happy about the Confederacy forming. They thought it would weaken the South's power over the U.S. government. However, President Abraham Lincoln wanted to keep the country together.

Twelve days after the attack on Fort Sumter, Phillips changed his mind. He strongly supported the war. He was unhappy with Lincoln's slow actions to end slavery. Because of this, Phillips opposed Lincoln's reelection in 1864. This was different from Garrison, who supported Lincoln.

In 1862, Phillips' nephew, Samuel D. Phillips, died. He had gone to Port Royal, South Carolina. He was helping formerly enslaved people there start their new lives as free individuals.

Women's Rights Activism

Phillips was also an early supporter of women's rights. In 1840, he tried to get American women delegates seated at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. This effort was not successful.

In 1846, he wrote in The Liberator newspaper. He called for women to have rights to their own property and money. He also wanted them to have the right to vote. He believed that controlling their own money would help women develop their character and intelligence. He felt this would also lead to better education for women.

I have always thought that the first right restored to woman would be that of the full and unfettered control of all her property and earnings, whether she were married or unmarried. This, too, is, in one sense, the most important to be secured. The responsibility of such a trust at once develops character and intellect, and goes far to afford the hitherto mission and indispensable motive to education. Next in order of importance and time, comes the ballot. So it has always been with all disfranchised classes; first property—then political influence and rights; the first prepares for, gives weight to, challenges, finally secures the second.

In 1849 and 1850, he helped Lucy Stone with the first campaign for women's voting rights in Massachusetts. He wrote the petition and an appeal for signatures. They repeated this effort for two more years. They sent hundreds of signatures to the state government.

Phillips was a member of the National Woman's Rights Central Committee. This group organized yearly meetings in the 1850s. He was a close advisor to Lucy Stone. He often wrote the statements of principles and goals for these meetings. His speech from the 1851 convention, called "Freedom for Woman," was used for women's rights for many years.

After the Civil War

After the Civil War ended, Phillips focused on the period known as Reconstruction. In 1864, he gave a speech in New York. He argued that formerly enslaved Black men should be allowed to vote. He believed this was necessary for Southern states to rejoin the Union.

Unlike some other white abolitionists, Phillips felt that securing voting rights for freedmen was essential. He argued that without the right to vote, the rights of freedmen would be crushed by white Southerners.

He was disappointed when the Fourteenth Amendment was passed without including voting rights for Black men. He strongly opposed President Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction plans. Phillips supported Ulysses S. Grant and the Republican Party in the 1868 election. The Republicans passed the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. This amendment made Black suffrage (the right to vote) a part of the Constitution. However, the goal of giving land to freedmen was never achieved.

In 1879, Phillips said that Black voting and political involvement during Reconstruction were not failures. He believed the main mistake was not giving land to the freedmen. He praised Black voters and their bravery against attacks from groups like the first Ku Klux Klan.

As Reconstruction ended, Phillips turned his attention to other issues. These included women's rights, the right to vote for everyone, the temperance movement (reducing alcohol use), and the labor movement.

Equal Rights for Native Americans

Phillips also worked hard to gain equal rights for Native Americans. He argued that the Fifteenth Amendment should also grant citizenship to Native Americans. He suggested creating a new government position to protect Native American rights.

Phillips helped create the Massachusetts Indian Commission. He worked with Native American rights activist Helen Hunt Jackson. Although he often criticized President Ulysses S. Grant, he worked with Grant's administration on appointing fair Indian agents. Phillips spoke out against using the military to solve problems with Native Americans in the West. He accused General Philip Sheridan of trying to wipe out Native American groups.

Public opinion turned against Native American supporters after the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. But Phillips continued to support the land claims of the Lakota (Sioux). In the 1870s, Phillips organized public talks for reformer Alfred B. Meacham. He also brought in Native Americans affected by the country's policy of moving them from their lands. These included the Ponca chief Standing Bear and the Omaha writer Susette LaFlesche Tibbles.

Illness and Death

By late January 1884, Phillips was suffering from heart disease. He gave his last public speech on January 26, 1884. His doctor had told him not to speak. Phillips spoke at the unveiling of a statue for Harriet Martineau. At the time, he said he thought it would be his last speech.

Phillips died at his home in Boston on February 2, 1884.

His funeral was held four days later. His body was taken to Faneuil Hall, where people could pay their respects. Phillips was first buried at Granary Burying Ground. In April 1886, his remains were moved and reburied at Milton Cemetery in Milton.

Many people held memorial services for Phillips. Speakers praised him as a friend to all people and a great reformer.

Recognition and Legacy

In 1904, the Chicago Public Schools opened Wendell Phillips High School in his honor.

In July 1915, a monument was put up in Boston Public Garden to remember Phillips. It has his famous words: "Whether in chains or in laurels, liberty knows nothing but victories."

The Phillips Neighborhood of Minneapolis is also named after him.

A quote from his speech on January 20, 1861, is on many courthouses: "I think the first duty of society is justice."

The Wendell Phillips Award was created in 1896. It is given every year to a student at Tufts University. Harvard University also gives the Wendell Phillips Prize to its best speaker in the sophomore class.

The Wendell Phillips School in Washington, D.C., was named for him in 1890.

Images for kids

-

A daguerrotype by Mathew Brady of Wendell Phillips in his forties

-

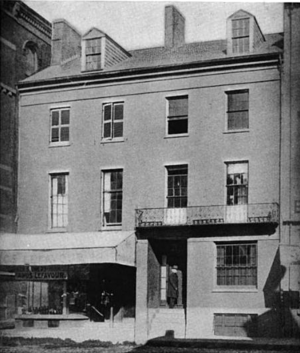

Phillips lived on Essex Street, Boston, 1841–1882

-

Wendell Phillips Memorial at Boston Public Garden.

See also

In Spanish: Wendell Phillips para niños

In Spanish: Wendell Phillips para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |