Boston Vigilance Committee facts for kids

The Boston Vigilance Committee was a special group formed in Boston, Massachusetts, between 1841 and 1861. Its main goal was to help enslaved people who had escaped from the South. They wanted to protect these brave individuals from being captured and forced back into slavery.

The Committee helped hundreds of escapees. Most of these people arrived secretly on ships and stayed in Boston for a short time. Then, the Committee helped them travel further to places like Canada or England, where they would be truly free.

Members of the Committee worked with people who donated money and with "conductors" of the Underground Railroad. The Underground Railroad was a secret network of safe houses and routes. The Committee provided money, safe places to stay, medical care, legal help, and transportation. They also watched out for "slave catchers," who were people hired to find and return escaped slaves. When slave catchers came to town, the Committee spread the word quickly. Some members even took part in daring rescue missions.

Contents

History of the Committee

How the Committee Started (1841)

The Boston Vigilance Committee officially began on June 4, 1841. It was started after a public call from Charles Turner Torrey and others. The first meeting was held in a place called Marlboro Chapel in Boston. Many different kinds of people attended, including both white and Black citizens, and people from various religious groups.

At this first meeting, they decided on their purpose:

The goal of this group is to make sure that Black people can enjoy their legal rights. To do this, we will use every legal, peaceful, and Christian method, and no other.

After a while, Charles Torrey left Boston. In 1842, a court ruling made it harder for the Committee to help escaped slaves without breaking the law. Because of this, some Black Bostonians formed a new group called the New England Freedom Association. This group was willing to act outside the law if needed. Eventually, the New England Freedom Association joined with the Boston Vigilance Committee.

In 1842, a lawyer named Samuel E. Sewall helped George Latimer, an escaped slave who was arrested in Boston. When Latimer's case was lost, Sewall and others bought his freedom.

The Committee might have stopped working for a short time around 1847. But it became very active again a few years later.

The Committee Gets Reorganized (1850)

On September 18, 1850, a new law called the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed. This law made it a crime to help escaped slaves and required free states to help capture and return them. This made the Committee's work much more dangerous.

To respond to this new law, the Boston Vigilance Committee held a huge public meeting on October 4, 1850, in Faneuil Hall. Famous abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and Theodore Parker spoke to a very large crowd. Many people who joined the Committee at this time might not have known about its earlier beginnings.

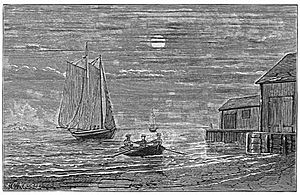

The reorganized Committee had over 200 members. It included both Black and white people. Many wealthy members helped by providing money. Others, like Lewis Hayden, who helped rescue Shadrach Minkins, provided more direct help. John Swett Rock was the Committee's medical officer, and Austin Bearse, a ship captain, secretly brought escaped slaves into and out of Boston.

Several lawyers, such as Richard Henry Dana Jr. and Samuel Edmund Sewall, defended escaped slaves and their helpers in court. Some members, like Theodore Parker and Samuel Gridley Howe, also secretly supported John Brown's efforts to fight slavery.

Even people who were not official members often helped and were paid back by the Committee. For example, the Reverend Leonard Grimes of the Twelfth Baptist Church received money for helping people travel.

While the Committee had members from different races, most of the white members preferred to give legal and financial help. Black Bostonians often did most of the dangerous, hands-on rescue work. They had more at stake and were more willing to use force if needed.

The Boston Vigilance Committee was special because its treasurer kept very detailed records from 1850 to 1861. These records show how risky their work was, as helping escaped slaves was illegal and could lead to jail time and big fines.

The Story of Ellen and William Craft

In 1848, Ellen and William Craft made a daring escape from slavery in Georgia and reached the North. Their story became well-known, which made them targets for slave catchers. In 1850, they were living in Boston. After the Fugitive Slave Act passed, warrants were issued for their arrest.

When two slave catchers from Georgia arrived in Boston, William sent Ellen to hide. He stayed with Lewis Hayden, a key Committee member. Other Committee members worked to bother the slave catchers. They put up posters describing the men and had them arrested many times for small things like slander or smoking in the street. Each time, the slave catchers were bailed out by people who supported slavery.

The Crafts stayed hidden in Boston for several weeks before escaping to England in January 1851. They were married by Theodore Parker in November 1850.

The Story of Shadrach Minkins

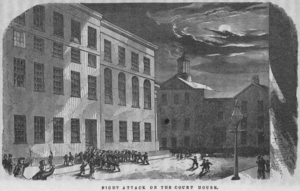

In 1850, Shadrach Minkins escaped from Virginia and became a waiter in Boston. In February 1851, he was arrested by federal officers at work and taken to the courthouse. The Boston Vigilance Committee quickly hired a team of lawyers to defend him. They also put up posters warning people about slave catchers. Many protesters gathered outside the courthouse, demanding Minkins' freedom.

On February 15, 1851, a group of about 20 Black activists, led by Lewis Hayden, stormed the courthouse. They freed Minkins by force. Among them were John J. Smith, a barber who later became a state representative, and John P. Coburn, who led a Black militia group. Minkins was quickly taken away and hidden. With the help of the Underground Railroad, he eventually reached Canada.

Several Committee members, including Lewis Hayden, were arrested for their part in the rescue. The Committee hired lawyers to defend them, and everyone was found not guilty.

The Story of Thomas Sims

Thomas Sims had escaped slavery in Georgia and was living in Boston when he was captured by federal officers in 1851. The Committee hired lawyer John Albion Andrew to help him. Sims was held in a room on the third floor of the federal courthouse. Committee members tried to plan an escape by placing mattresses under his window so he could jump, but the window was barred before they could act.

The government sent U.S. Marines to march Sims through the streets of Boston. He was put on a warship and sent back to Georgia. Sims was sold to a new slaveholder in Mississippi, but he escaped again in 1863 and returned to Boston.

The Story of Anthony Burns

In 1853, Anthony Burns escaped slavery in Virginia and found work in a clothing shop in Boston. In May 1854, he was arrested and held in the courthouse. Lawyer John A. Albion led a team of Vigilance Committee lawyers in an attempt to defend him, but they were not successful. Wendell Phillips and Theodore Parker offered money to buy Burns's freedom, but their offer was refused.

That night, a crowd led by Reverend Thomas Wentworth Higginson attacked the courthouse. They broke down a door and tried to go upstairs, but armed guards stopped them. During the struggle, a marshal was killed. When soldiers arrived, the crowd scattered, and Burns remained trapped.

When it was time for Burns to be sent back to Virginia, many Bostonians protested in the streets. The Vigilance Committee paid for "alarm banners" and "alarm bells" to be used in the protest. They also handed out many anti-slavery pamphlets. They started a petition to remove Judge Edward G. Loring, who had ordered Burns to be returned to slavery. Judge Loring was eventually removed from his job.

Weeks later, Higginson, Phillips, and Parker were accused of causing a riot because of their anti-slavery speeches. The Committee hired lawyers to defend them, and the charges were dropped. Reverend Grimes and other abolitionists raised money to buy Burns's freedom, and he eventually returned to Massachusetts.

When the Committee Ended

The Boston Vigilance Committee stopped its work in April 1861. This was about ten years and seven months after the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed. The start of the American Civil War around this time likely changed the focus of anti-slavery efforts.

Notable members

A more complete list can be found in Austin Bearse's 1880 book, Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston.

- Amos Bronson Alcott

- John A. Andrew

- Edward Atkinson

- John Augustus

- Austin Bearse

- John A. Bolles

- John Botume Jr.

- Thomas Tracy Bouvé

- Henry Ingersoll Bowditch

- William Ingersoll Bowditch

- Anson Burlingame

- Thomas Carew

- William Henry Channing

- John P. Coburn

- Nathaniel Colver

- Richard Henry Dana Jr.

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Timothy Gilbert

- Daniel W. Gooch

- Lewis Hayden

- Thomas Wentworth Higginson

- Richard Hildreth

- John T. Hilton

- Charles F. Hovey

- Samuel Gridley Howe

- Timothy W. Hoxie

- Francis Jackson

- William Jackson

- John P. Jewett

- Joel W. Lewis

- Ellis Gray Loring

- James Russell Lowell

- Bela Marsh

- Samuel May, Jr.

- Robert Morris

- William Cooper Nell

- Theodore Parker

- Wendell Phillips

- Henry Prentiss

- Edmund Quincy

- John Swett Rock

- Samuel E. Sewall

- Joshua Bowen Smith

- Isaac H. Snowden

- John Murray Spear

- Lysander Spooner

- Charles Turner Torrey

- Mark Trafton

- Elizur Wright

See also

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |