Thomas Sims facts for kids

Thomas Sims was an African American man who escaped from slavery in Georgia. He fled to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1851. However, he was arrested that same year under a strict law called the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. After a court hearing, he was forced to return to slavery.

Years later, in 1863, Sims escaped again and made it back to Boston. He later achieved an important position in the U.S. Department of Justice in 1877. Thomas Sims was one of the first people to be forcibly returned from Boston under the Fugitive Slave Act. His case was a big setback for people who wanted to end slavery, known as abolitionists. It showed how much power slavery had in American society and government. His story was one of many events that led to the American Civil War.

Contents

Early Life

Thomas Sims was born in Georgia around 1828. His parents, James Sims and Minda Campbell, were both enslaved by a rice planter named James Potter. Thomas had several brothers and sisters, including James M. Simms, who also became a well-known African American. Before he escaped, Thomas Sims worked as a bricklayer for Mr. Potter. He also married a free African American woman and had children with her.

Escaping Slavery

Sims made his escape on February 21, 1851, when he was 23 years old. He hid on a ship called the M. & J.C. Gilmore. On March 6, just before the ship arrived in Boston, the crew found Sims. He tried to convince them he was a free man from Florida, but they didn't believe him and locked him in a cabin.

Sims managed to escape from the cabin before authorities arrived. From then until his arrest in April, he stayed at 153 Ann Street. This was a boarding house for African American sailors. Newspaper reports from that time said he "made no effort to conceal himself" while living there. However, he was caught after he sent his address to his wife, asking her for money.

Arrest and Hearing

When James Potter, Sims's owner, found out where Sims was, he sent his agent, John B. Bacon, to capture him. Bacon worked with Seth J. Thomas and Boston authorities, including U.S. Commissioner George T. Curtis. On April 3, 1851, Sims was arrested. There was a struggle during his arrest.

The hearing for Sims took place three days after his arrest. It attracted a lot of attention from abolitionists and people in the North. Extra security was put in place at the Court House. Between 100 and 200 police officers were there, and chains were placed around the courthouse. This was to stop crowds from rushing the building.

However, these chains accidentally became a symbol of how much power slavery had, even in the North. People who needed to enter the Court House had to bend down and go under the chains. The poet Henry Longfellow wrote that it was a "Shame that the great Republic... should stoop so low as to become the Hunter of Slaves." Chief Justice Wells was one of the few who refused to bend down. He felt it lowered his dignity and the dignity of Boston.

The "trial" (Commissioner Curtis was not a judge) was about whether a person's freedom or an owner's right to property was more important. Each side tried to explain why their view was stronger. The side trying to send Sims back showed papers proving he was a former slave and brought witnesses. Sims's defense team had a harder time because the Fugitive Slave Act made it easier to send people back. This law said that escaped slaves on trial could not speak for themselves as evidence. Also, the law required a quick hearing, so the defense didn't have much time to find their own witnesses.

Sims's lawyer, Robert Rantoul Jr., argued that the Constitution didn't allow people to be sent back without full proof. He also questioned if the Commissioner, who wasn't a judge, had the right to send Sims back. Commissioner Curtis gave them the weekend to prepare more, wanting to be fair. Rantoul later argued that Sims's rights to life, liberty, and property were being taken away, which went against the 5th Amendment. He also tried to challenge if the Fugitive Slave Act itself was legal.

The Boston Vigilance Committee tried to find ways to help Sims outside the courtroom. They tried to get a writ of replevin (a legal order to get property back) and to ask for habeas corpus (a legal order to bring a person before a court). But neither attempt worked.

At the end of the hearing, the court decided that Sims would be sent back to the South. Commissioner Curtis said he would have preferred a real judge to make the decision, but none were available. Sims was officially declared the property of James Potter.

Sent Back to Slavery

After the court hearing, Sims was sent back to Georgia, despite strong protests from abolitionists. The Boston Vigilance Committee, which had helped another escaped slave named Shadrach Minkins get away, became desperate. They came up with several plans to free Sims. One idea was to put mattresses under Sims's cell window so he could jump out and escape in a horse and carriage. However, the sheriff blocked the window before they could act.

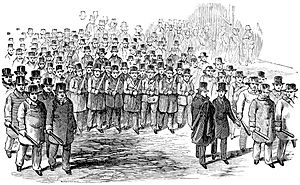

On April 13, Sims was marched to a ship and returned to Georgia with military protection. Sims cried out that he would rather be killed and asked for a knife many times. Many people marched with Sims to the dock to show their support. When he arrived back in Savannah, Sims was punished and sold in a slave auction to a new owner in Mississippi.

Later Life

Later, Charles Devens, the U.S. Marshal who had been ordered to return Sims to Georgia, tried to buy Sims's freedom, but he was not successful. However, Sims managed to escape again. He returned to Boston in 1863 during the Civil War.

Devens did not forget about Sims. When Devens became the U.S. Attorney General in 1877, he appointed Sims to a position in the U.S. Department of Justice.

How People Reacted

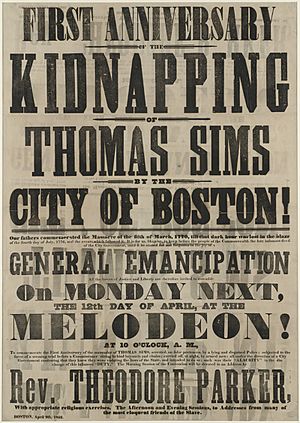

The "Sims Tragedy" caused a lot of anger among abolitionists in Massachusetts and gained sympathy from many others. The next year, in 1852, his arrest and hearing were remembered in a church ceremony.

Three years after Sims's arrest, Judge Edward G. Loring ordered another escaped slave, Anthony Burns, back to slavery in Virginia. Sims's and Burns's cases are often compared. Like Sims, Burns was escorted by U.S. Marines to a ship going to Virginia. By the time Burns was sent away, his story was so famous that 50,000 people watched federal officers take him to the dock. Within two years, Burns was back in Boston after abolitionists raised $1,300 to buy his freedom.

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |