Samuel Gridley Howe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Samuel Gridley Howe

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 10, 1801 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | January 9, 1876 (aged 74) Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Mount Auburn Cemetery |

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Physician, abolitionist |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

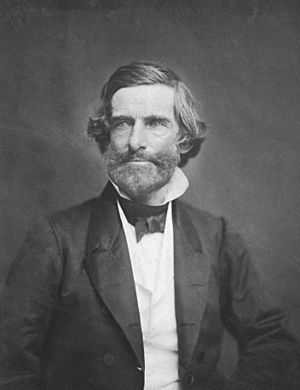

Samuel Gridley Howe (born November 10, 1801 – died January 9, 1876) was an American doctor. He was also an abolitionist, meaning he worked to end slavery. Howe was a strong supporter of education for people who were blind. He helped start and was the first leader of the Perkins Institution.

In 1824, he went to Greece to help in their revolution as a surgeon. He even led troops. He also helped refugees and brought many Greek children to Boston for their education. Later, as an abolitionist, Howe investigated the lives of formerly enslaved people. He helped them transition to freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Samuel Gridley Howe was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on November 10, 1801. His father, Joseph Neals Howe, owned ships and made ropes. His mother, Patty (Gridley) Howe, was known for her beauty. Samuel's grandfather, Edward Compton Howe, was part of the famous Boston Tea Party.

Howe went to Boston Latin School. His daughter later wrote that he didn't have happy memories of school. Boston was a very exciting place for politics back then. His father didn't want him to go to Harvard University because it was full of Federalists. So, in 1818, Howe went to Brown University. He admitted later that he wished he had studied more seriously. After Brown, he went to Harvard Medical School and became a doctor in 1824.

Helping in the Greek Revolution

After becoming a doctor, Howe didn't stay in Massachusetts for long. In 1824, he was very excited about the Greek Revolution. He admired Lord Byron, a famous poet who also helped Greece. Howe sailed to Greece and joined the Greek army as a surgeon.

In Greece, he did more than just surgery. He was brave and a good leader. People called him "the Lafayette of the Greek Revolution." In 1827, Howe came back to the United States. He wanted to raise money and supplies to help with the hunger and hardship in Greece. He collected about $60,000. He used this money for food, clothes, and to set up a place for refugees. He also wrote a book about the revolution called Historical Sketch of the Greek Revolution.

Samuel Gridley Howe brought many Greek children who were refugees back to the United States. He wanted them to get an education. Two of these children became important later on: John Celivergos Zachos, who fought against slavery and for women's rights, and Christophorus P. Castanis. Castanis wrote a book about his experiences. Howe also continued his medical studies in Paris. He even took part in the July Revolution there because he believed in a republican government.

Work for the Blind

In 1831, Howe returned to the United States. A friend, John Dix Fisher, told him about a school for the blind in Paris. A group in Boston asked Howe to help start a similar school there. He was very eager to help. He traveled to Europe to learn more about schools for the blind.

While in Europe, he also helped Polish revolutionaries. He was supposed to give them money. But the Poles had been defeated. Howe went to distribute supplies and funds to Polish officers who didn't want to go home. In Berlin, he was arrested and put in prison. He managed to destroy or hide any letters that could get him in trouble. After five weeks, he was released thanks to the United States Minister in Paris.

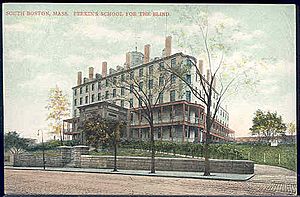

Howe came back to Boston in July 1832. He started teaching a few blind children at his father's house. This was the beginning of the famous Perkins Institution. The school quickly showed great progress. The state government approved funding for it. A wealthy Boston trader, Thomas Handasyd Perkins, donated his mansion for the school. In 1839, the school moved to a new location. It became known as the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts Asylum.

Howe was the main leader and inspiration for the school. He started a printing office to make books for the blind. This was the first time this was done in the United States. He worked tirelessly to promote the school. In 1837, he welcomed Laura Bridgman, a young girl who was deaf and blind. She became famous as the first deaf-blind person in the U.S. to be successfully educated. Howe taught Bridgman himself. She learned the manual alphabet and how to write.

Howe created many new ways to teach. He also improved how books were printed in Braille. He led the Perkins Institution for his whole life. He also helped start many similar schools across the country.

Marriage and Family

On April 23, 1843, when he was 41, Howe married Julia Ward. She was the daughter of a rich New York banker. Julia strongly supported ending slavery. She later worked for women's right to vote. She also wrote the famous song "Battle Hymn of the Republic" during the American Civil War.

Their marriage had strong feelings and disagreements. Julia wanted to have a career outside of being a mother. While Howe was progressive in many ways, he believed a wife's place was in the home. He didn't support Julia having a career.

They had six children:

- Julia Romana Howe (1844–1886)

- Florence Marion Howe (1845–1922), a writer who won a Pulitzer Prize.

- Henry Marion Howe (1848–1922), who studied metals.

- Laura Elizabeth Howe (1850–1943), also a Pulitzer Prize-winning author.

- Maud Howe (1854–1948), another Pulitzer Prize-winning author.

- Samuel Gridley Howe, Jr. (1858–1863), who died young.

Laura and Florence were very close to their father. Florence later became a strong supporter of women's right to vote, like her mother.

Fighting Against Slavery

Howe first publicly joined the fight against slavery in 1846. He was a candidate for Congress but did not win. He helped start an antislavery newspaper called the Boston Daily Commonwealth. He edited it with his wife, Julia Ward Howe. He was also an important member of the Kansas Committee in Massachusetts.

Howe was interested in the plans of John Brown, an abolitionist. Howe funded some of Brown's work. However, he did not agree with Brown's attack on Harpers Ferry. After Brown was arrested, Howe briefly went to Canada to avoid being charged.

Howe strongly opposed the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. This law said that even in free states, people had to help catch enslaved people who had escaped. In May 1854, Howe and other abolitionists tried to free Anthony Burns, an enslaved man who had been captured in Boston. They broke into Faneuil Hall to rescue him. Howe declared, "No man's freedom is safe until all men are free." Federal troops stopped their attempt, and Burns was sent back to Virginia. However, the abolitionists later raised money to buy Burns's freedom.

In October 1854, Howe helped another escaped enslaved man. This man had hidden on a ship coming into Boston Harbor. Howe and others helped him avoid slave-catchers and reach freedom.

In 1863, during the American Civil War, Howe was part of the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission. He traveled to the Deep South and to Canada. He wanted to see how formerly enslaved people were living. He found that their lives in Canada were much better. They could earn a living, marry, and go to school and church without fear. He wrote a report about his findings. This report helped lead to the creation of the Freedmen's Bureau. This bureau was set up to help formerly enslaved people in the South.

Civil War and Reconstruction Efforts

During the Civil War, Howe was a leader in the Sanitary Commission. This group raised money to improve hygiene in Union army camps. They wanted to prevent diseases like dysentery and typhoid. The Commission also provided supplies and medical help to soldiers.

After the Civil War, Howe worked with the Freedmen's Bureau. This continued his work as an abolitionist. The Freedmen's Bureau helped newly freed enslaved people in the South. They provided housing, food, clothes, education, and medical care. They also tried to help families reunite after being separated by slavery.

Helping Others

Howe also worked with Dorothea Dix to start the Massachusetts School for Idiot and Feeble-Minded Youth. This was the oldest publicly funded school in the Western Hemisphere for people with mental disabilities. He started the school in 1848. At that time, "idiot" was a polite term for people with mental and intellectual disabilities. Howe successfully taught these students. However, some people thought these students should stay in such schools forever. Howe disagreed. He believed people with mental disabilities had rights. He argued that separating them from society would be harmful.

In 1866, Howe gave a speech at a new school for the blind in New York. He warned against separating people based on their disabilities. He said, "We should be careful about creating such separate communities... for any children and youth; but especially for those who have natural weaknesses." He believed that people with disabilities should live among others. He felt that blind children should be with those who can see, and mute children with those who can speak.

Howe also founded the State Board of Charities of Massachusetts in 1863. This was the first board of its kind in the United States. He was its chairman until 1874. In 1866, Howe made a final trip to Greece. He brought help to refugees from Crete during the Cretan Revolution.

Later Years and Death

Samuel Howe stayed active in politics and helping others until the end of his life. In 1865, he spoke about a progressive tax system. This meant that wealthier people would pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes. He believed that society could not be truly fair if there was a huge gap between rich and poor. He said that freeing enslaved people and doing charity work alone were not enough.

In 1870, he was part of a group sent by President Grant. They were to see if the United States should take over Santo Domingo. President Grant wanted to annex the island. However, Senator Charles Sumner, a friend of Howe's, was against this. In the end, Howe's committee agreed with Sumner. Grant was very angry and had Sumner removed from his leadership position in the Senate.

Samuel Gridley Howe died on January 9, 1876. He is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Legacy and Honors

A World War II ship, the SS Samuel G. Howe, was named in his honor.

See also

In Spanish: Samuel Gridley Howe para niños

In Spanish: Samuel Gridley Howe para niños

- Jonathan Miller

- John Dennison Russ

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |