Amos Bronson Alcott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

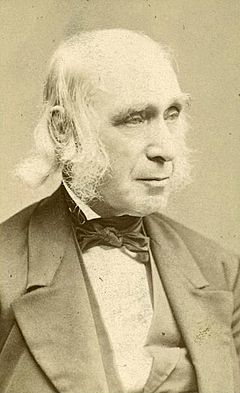

Amos Bronson Alcott

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Amos Bronson Alcox

November 29, 1799 Wolcott, Connecticut, U.S.

|

| Died | March 4, 1888 (aged 88) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Resting place | Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S.A. |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

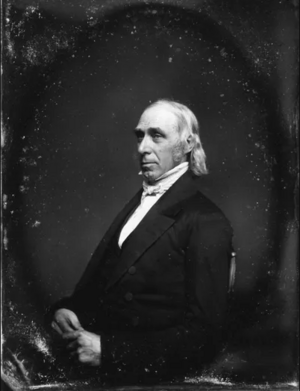

Amos Bronson Alcott (November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. He was known for his new ways of teaching young students. He liked to talk with students instead of just lecturing them. He also avoided traditional punishments.

Alcott believed in making people better. He supported a plant-based diet and was against slavery. He also fought for women's rights. He was born in Wolcott, Connecticut in 1799. He had little formal schooling himself. He first tried to be a traveling salesman. But he soon felt this job was not good for his spirit. So, he became a teacher.

His teaching ideas were often new and sometimes caused arguments. This meant he rarely stayed in one place for long. His most famous school was the Temple School in Boston. His experiences there led to two books. These were Records of a School and Conversations with Children on the Gospels.

Alcott became friends with Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was an important figure in transcendentalism. This was a philosophical movement. However, his writings for this movement were often hard to understand. Based on his ideas for human perfection, Alcott started Fruitlands. This was an experiment in community living. But the project failed after only seven months.

Alcott and his family often struggled with money. Still, he kept working on educational projects. He opened a new school in 1879, late in his life. He died in 1888. Alcott married Abby May in 1830. They had four daughters who survived. Their second daughter was Louisa May Alcott. She wrote about her family experiences in her famous novel Little Women in 1868.

Contents

Alcott's Life and Work

Growing Up in New England

Amos Bronson Alcott was born in Wolcott, Connecticut. This was on November 29, 1799. His parents were Joseph Chatfield Alcott and Anna Bronson Alcott. The family lived in an area called Spindle Hill. Bronson was the oldest of eight children. He later changed the family name spelling to "Alcott." He also dropped his first name, Amos.

Bronson started school at age six in a one-room schoolhouse. But his mother taught him to read at home. He left school at age 10. At 13, his uncle invited him to prepare for college. But Bronson left after only a month. He taught himself from then on. He was not very social. His closest friend was his cousin, William Alcott. They shared books and ideas.

When he was 15, he worked for a clockmaker named Seth Thomas. At 17, he passed a teaching exam. But he could not find a teaching job. So, he became a traveling salesman in the American South. He sold books and other goods. He hoped to earn money for his parents. But he soon spent most of his earnings. He worried about his spiritual well-being in this job. He later wrote about this time in his book, New Connecticut.

Early Career and Marriage

By 1823, Alcott returned to Connecticut. He was in debt. His father helped him out. He then got a job as a schoolteacher in Cheshire. His uncle helped him find this job. He quickly began to change the school. He added backs to benches and improved lighting. He also gave each student their own slate. He was influenced by the Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. Alcott even renamed his school "The Cheshire Pestalozzi School."

His new teaching style caught the eye of Samuel Joseph May. May introduced Alcott to his sister, Abby May. Abby thought Alcott was "an intelligent, philosophic, modest man." She liked his ideas about education. But local people in Cheshire did not like his methods. Many students left his school.

In 1827, Alcott started teaching in Bristol, Connecticut. He used the same methods. But again, people in the community were against him. He lost his job by March 1828. He moved to Boston in April 1828. He was very impressed with the city. He opened the Salem Street Infant School in June. Abby May applied to be his assistant. Instead, they got engaged and married on May 22, 1830. He was 30, and she was 29.

Around this time, Alcott also spoke out against slavery. In November 1830, he and William Lloyd Garrison started an early anti-slavery group. Alcott also joined the Boston Vigilance Committee. This group helped runaway slaves.

His school in Boston was losing students. A wealthy Quaker, Reuben Haines III, suggested a new school in Pennsylvania. Alcott accepted. He and his pregnant wife moved there. Their first child, Anna Bronson Alcott, was born on March 16, 1831. Their second daughter, Louisa May Alcott, was born on November 29, 1832. This was on her father's birthday.

The school in Germantown did not do well. Their helper, Haines, died. The family faced money problems again. In 1833, they moved to Philadelphia. Alcott ran a day school there. His methods were still controversial. He began to think Boston was the best place for his ideas. He got support from important people like William Ellery Channing.

Innovative Teaching Methods

On September 22, 1834, Alcott opened the Temple School. It had about 30 students, mostly from rich families. Classes were held at the Masonic Temple in Boston. His assistants included Elizabeth Palmer Peabody and later Margaret Fuller.

The school became famous, then infamous. This was because Alcott taught by "conversation" instead of textbooks. He also questioned the Bible. And he allowed a Black girl to join his classes. This was very unusual at the time.

Before 1830, writing lessons were mostly about memorizing rules. But Alcott and other reformers wanted students to write about their own experiences. They believed students should learn by expressing their personal thoughts.

Alcott wanted to teach students to think for themselves. He focused on talking and asking questions. He also gave lessons in "spiritual culture." This included discussing the Gospels. He decorated his classroom to inspire learning. He used paintings, books, and busts of thinkers like Plato and Jesus.

On June 24, 1835, another daughter was born. She was named Elizabeth Peabody Alcott. Later, her mother changed her name to Elizabeth Sewall Alcott.

In 1835, Elizabeth Peabody wrote a book about the Temple School. It was called Record of a School. Alcott also published Conversations with Children on the Gospels. Many people did not like his methods. They found his discussions on the Gospels almost disrespectful. The book did not sell well.

The Temple School was criticized in newspapers. By 1837, Alcott had only 11 students left. The school closed. Alcott faced more money problems. He continued his progressive teaching. He even admitted an African American child to a later school. He refused to expel her despite protests.

A Transcendental Thinker

Starting in 1836, Alcott joined the Transcendental Club. This group included thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson. They were liberal thinkers who met to discuss ideas. Alcott called their meetings "Symposiums."

In 1840, Alcott moved to Concord. Emerson encouraged him. He rented a home called Dove Cottage. Emerson, who supported Alcott's ideas, tried to help him with his writing. But Alcott's writing was often hard to understand.

Alcott wrote "Orphic Sayings" for a journal called The Dial. Many people found them silly and unclear. For example, one saying was: "Nature is quick with spirit."

With Emerson's help, Alcott visited England in 1842. He met people who admired his teaching methods. Two of them, Charles Lane and Henry C. Wright, came back to the United States with him. Lane and his son even moved in with the Alcotts.

Alcott was against slavery. He refused to pay his poll tax in protest. This was because President Tyler wanted to add Texas as a slave territory. Alcott's protest inspired Henry David Thoreau. Thoreau's similar protest led to his famous essay "Civil Disobedience."

The Fruitlands Experiment

Alcott and Charles Lane wanted to create a Utopian community. Alcott was in debt, so Lane bought a farm in Harvard, Massachusetts. They moved to the farm on June 1, 1843. They named it "Fruitlands." They hoped to live in harmony with nature and each other.

They tried to live without money as much as possible. They called themselves a "consociate family." They avoided using animal labor at first. But they later had to use some cattle. They did not drink coffee, tea, or alcohol. They also avoided milk and warm baths. Their clothes were made without animal products.

Alcott had high hopes for Fruitlands. But he was often away, trying to find more members. The community was never successful. Much of the land was not good for farming. Alcott admitted they were not ready for such a life. The project failed after seven months. Only 13 people joined, including the Alcotts and Lanes.

Lane left the project. He moved to a nearby Shaker community. After Lane left, Alcott became very sad. Abby May believed Lane had tried to break up her family. The Alcotts had to leave Fruitlands.

The Fruitlands experience was hard for the family. Louisa May Alcott, who was ten at the time, later wrote about it. She described how the "band of brothers" quickly lost their excitement for farm work.

Back in Concord

In 1844, Alcott moved his family to Still River. Then, in 1845, they returned to Concord. They lived in a home they called "The Hillside." This home was later renamed "The Wayside" by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Emerson and Sam May helped the Alcotts get the house.

Louisa May Alcott started writing seriously while living there. She later said these were the happiest years of her life. Many parts of her novel Little Women are based on this time. Alcott fixed up the house and cared for the land.

The Alcotts often had visitors at The Hillside. They secretly hosted runaway slaves. This was part of the Underground Railroad. Alcott was also against the Mexican–American War. He saw it as a way to expand slavery.

In 1848, Abby May wanted to leave Concord. She felt it was "cold" and "soulless." The family rented out The Hillside and moved to Boston. There, Bronson Alcott gave a series of talks. He charged people to attend these "Conversations." In 1853, he was invited to teach a course at Harvard Divinity School.

The Alcotts moved back to Concord after 1857. They lived in the Orchard House until 1877. In 1860, Alcott became the superintendent of Concord Schools.

Civil War and Later Years

Alcott voted in a presidential election for the first time in 1860. He voted for Abraham Lincoln. Alcott was a strong abolitionist. He tried to help runaway slaves. He even tried to storm a courthouse to free a slave named Thomas Sims. He also protested the trial of Anthony Burns.

In 1862, Louisa May Alcott went to Washington, D.C. to be a nurse. In 1863, she became sick. Bronson went to bring her home. He briefly met Abraham Lincoln there. Louisa wrote about her experiences in Hospital Sketches.

Many of Alcott's friends died around this time. Henry David Thoreau died in 1862. Alcott helped arrange his funeral. Two years later, Nathaniel Hawthorne died. Alcott was a pallbearer. He worried that few of the important Concord people were left. In 1865, Lincoln was assassinated. Alcott called it "appalling news."

In 1868, Alcott met a publisher named Thomas Niles. Niles liked Hospital Sketches. Alcott asked him to publish a book of short stories by Louisa. Instead, Niles suggested she write a book about girls. Louisa was not interested at first. But she agreed to try. The result was Little Women. This book told a fictional story of the Alcott family. The father figure in the book was a chaplain away at war.

Alcott often gave talks across the United States. He called these "conversations." He talked about spiritual and practical topics. He shared the ideas of the American Transcendentalists. He often discussed Plato's philosophy. He spoke about connecting with nature and living a simple life.

Alcott's Final Years

Alcott published several books late in his life. These included Tablets (1868) and Concord Days (1872). Louisa May took care of her father in his last years. She bought a house for her sister Anna. Louisa and her parents moved in with Anna.

After his wife Abby May died in 1877, Alcott never returned to Orchard House. He was too heartbroken. He and Louisa May tried to write a memoir about Abby. But it was too painful. Louisa burned many of her mother's papers.

In 1879, Alcott and Franklin Benjamin Sanborn started a new school. It was called the Concord School of Philosophy. It held its first sessions in Alcott's study. In 1880, the school moved to the Hillside Chapel. Alcott held conversations there. He invited others to give lectures on philosophy and religion. This school was one of the first adult education centers in America. It continued for nine years.

In 1882, Alcott's friend Ralph Waldo Emerson died. Alcott visited him shortly before. Alcott himself moved to Boston in 1885. He was bedridden at the end of his life. Louisa May visited him on March 1, 1888. He died three days later, on March 4. Louisa May died only two days after her father.

Alcott's Beliefs and Impact

Teaching Without Punishment

Alcott was strongly against physical punishment for students. At the Temple School, he had a student superintendent each day. This student would report rule-breaking. The class would then discuss the punishment. Sometimes, Alcott would offer his own hand for a student to strike. He said any mistake was the teacher's fault. He believed this method caused shame and guilt. He thought this was better than fear from physical punishment.

His ideas on education are detailed in his essay, "Observations on the Principles and Methods of Infant Instruction." Alcott believed early education should bring out a child's natural thoughts. He thought infancy should focus on enjoyment. Learning, he said, was not about facts. It was about developing a thoughtful mind.

Alcott's teaching ideas were controversial. Some critics wondered if he thought children already knew everything. Even so, his ideas helped start adult education centers. They also laid the groundwork for future progressive education. Many of Alcott's teaching methods are still used today. These include encouraging students, art and music education, and learning through experience.

The Concord School of Philosophy closed after Alcott's death. But it reopened in the 1970s. It still holds summer talks in its original building. This building is now part of the Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association.

Modern Connections

Many of Alcott's ideas were seen as radical. But they are common themes in society today. These include vegetarian/veganism, sustainable living, and self-control. Alcott called his diet "Pythagorean." This meant he did not eat meat, eggs, butter, cheese, or milk. He only drank well water.

Alcott believed diet was key to human perfection. He linked physical health to mental improvement. He also saw a connection between nature and spirit. He spoke out against pollution. He encouraged people to help protect the environment. In a way, he predicted modern environmentalism.

Criticism and Legacy

Alcott's philosophical ideas were sometimes seen as unclear. He did not create a formal system of philosophy. He was influenced by Plato and German mysticism. Margaret Fuller called him "a philosopher of the balmy times of ancient Greece." She said people in Boston were as scared of him as Athenians were of Socrates.

Like Emerson, Alcott was always hopeful and individualistic. Writer James Russell Lowell called him "an angel with clipped wings." Emerson noted that Alcott was brilliant in conversation. But his writing was not as good. Emerson said, "When he sits down to write... he gives you the shells and throws away the kernel." His "Orphic Sayings" were often made fun of. People found them dense and meaningless.

Some modern critics say Alcott struggled to support his family. He himself worried about his future. He once wrote that he was "still at my old trade—hoping." Alcott often put his beliefs before his family's financial well-being. For example, he refused a high-paying teaching job. He did not agree with the school's beliefs.

However, the Alcotts created a home that produced two famous daughters. This was at a time when women were not usually encouraged to have independent careers.

Works by Alcott

- Observations on the Principles and Methods of Infant Instruction (1830)

- Conversations with Children on the Gospels (Volume I, 1836)

- Conversations with Children on the Gospels (Volume II, 1837)

- Concord Days (1872)

- Table-Talk (1877)

- Sonnets and Canzonets (1882)

- The Journals of Bronson Alcott (1966)

See also

In Spanish: Amos Bronson Alcott para niños

In Spanish: Amos Bronson Alcott para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |