Fruitlands (transcendental center) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Fruitlands

|

|

Farmhouse at Fruitlands (photographed in 2015)

|

|

| Location | Harvard, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Built | 1843 |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001761 |

| Added to NRHP | March 19, 1974 |

Fruitlands was a special community started in Harvard, Massachusetts, in the 1840s. It was founded by Amos Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane. They wanted to create a simple farming life based on ideas called transcendentalist principles. This meant focusing on spiritual things and living close to nature.

The people at Fruitlands had very strict rules. They ate no animal products, only drank water, and bathed in cold water. They also believed in not using artificial lights after dark. All property was shared, and they did not use animals for farm work.

This unique community lasted for only seven months. Farming without animals proved to be too hard. Today, the original farmhouse is part of the Fruitlands Museum. This museum also includes other historic buildings from the area.

Contents

The Fruitlands Experiment: A Unique Community

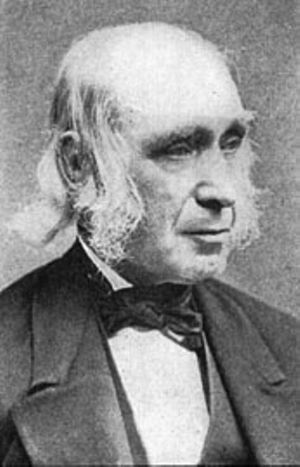

The idea for Fruitlands came from Amos Bronson Alcott in 1841. He was a teacher and believed in peaceful living. In 1842, he traveled to England to find people who shared his vision. There, he met Charles Lane, who joined him on his journey back to the United States in October 1842.

In May 1843, Charles Lane bought a 90-acre farm in Harvard, Massachusetts, for $1800. Alcott had the idea for Fruitlands, but he didn't buy the land. He had lost his money after his school failed. In July, Alcott announced their plans in a newspaper called The Dial. He said they had "liberated" the land from regular ownership. They moved to the farm on June 1 and named it "Fruitlands." This was a hopeful name, even though the property only had ten old apple trees.

The people at Fruitlands believed that land should not be bought or owned by individuals. Lane explained that they saw it as returning the land to "divine uses." About 14 people joined the community, including the Alcott and Lane families. By July, they had planted 8 acres of grains, 1 acre of vegetables, and 1 acre of melons. On July 8, the famous writer Ralph Waldo Emerson visited. He was impressed by the peaceful place and the hard work. However, he wisely noted, "I will not prejudge them successful... We will see them in December."

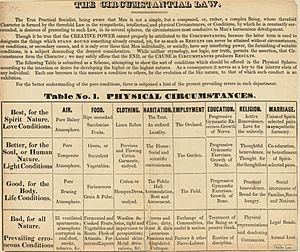

Alcott and Lane wrote an article together called "The Consociate Family Life." It was published in the New York Evening Tribune on September 1. They explained their goal was to improve society by living simply. This included simple diets, plain clothes, pure bathing, and clean homes.

Fruitlands ultimately failed during the winter after it opened. The main reasons were not enough food and disagreements among the residents. The harsh New England winter was too difficult for the community members.

Living by Special Rules: The Fruitlands Philosophy

Many of the ideas at Fruitlands came from Transcendentalism. This way of thinking suggested that God was a spirit found throughout the world, not just in traditional religious views. Alcott believed in a kind of spiritual freedom. He thought people should step away from worldly things to focus on their inner spirit. The Fruitlands members felt that becoming spiritually better was connected to being physically healthy. They believed that "outward abstinence is a sign of inward fullness." While Fruitlands was about working together, it also aimed for each person to improve themselves. Alcott also thought children had a perfect natural understanding. Because of this, he focused a lot on education. He hoped children's innocence would inspire the adults.

How Fruitlands Managed Money

The Fruitlands residents called themselves "the consociate family." They wanted to live apart from the world's economy. This meant they avoided trading, owned no personal property, and did not hire workers. Alcott and Lane thought that true freedom came from avoiding all money-related activities. Alcott especially believed the current economic system was wrong. To achieve their goals, they aimed to be self-sufficient. They planned to grow all their own food and make everything they needed. This way, they wouldn't have to trade or buy things from outside.

At first, Alcott and Lane based their ideas about shared property on the Shakers. Shakers also shared property. However, Shakers still traded handmade goods for items like coffee, tea, meat, and milk. Fruitlands went further. They removed animal products and stimulating drinks from their diets entirely. This meant they didn't need to trade for those supplies.

In the end, the Fruitlands community did not change the outside world's economy. It allowed its residents to live by their ideals, but it didn't force wider changes.

Daily Life and Food Choices

Life at Fruitlands began with a cold-water shower to cleanse the body. Their diet was very simple. It had no stimulating foods or animal products. They were strict vegans, meaning they didn't even eat milk or honey. Lane wrote that "Neither coffee, tea, molasses, nor rice tempts us." He added, "No animal substances neither flesh, butter, cheese, eggs, nor milk pollute our tables." Their meals usually consisted of fruit and water. Many vegetables, like carrots, beets, and potatoes, were not allowed. This was because they grew downwards into the earth, which was seen as less spiritual.

Fruitlands members wore only linen clothes and canvas shoes. Cotton fabric was forbidden because it was linked to slave labor. Wool was also banned because it came from sheep. Alcott and Lane believed animals should not be used for their meat or their work. So, they didn't use animals for farming. This was based on two beliefs. First, they thought humans should protect animals because animals were less intelligent. Second, they felt using animals "tainted" their work and food. This was because animals were not seen as "enlightened" or pure. As winter approached, Alcott and Lane made a small compromise. They allowed one ox and one cow to help.

People Who Lived at Fruitlands

There were no official rules for joining Fruitlands. Also, no formal records of members were kept. Many people stayed for only a short time. Most lists of residents come from the journals of Alcott's wife, Abby May. The residents of Fruitlands were sometimes called "consecrated cranks." They followed strong beliefs in simplicity, honesty, and kindness.

- Amos Bronson Alcott – Born in 1799, he was a well-known educator and Transcendentalist. He believed in new teaching methods. These included no physical punishment, and adding field trips, exercise, art, and music to school lessons.

- Abigail Alcott – Abigail was Bronson Alcott's wife and also a reformer. She was one of only two adult women at Fruitlands. She was mainly in charge of the house, the farm, and raising her four children.

- Louisa May Alcott – She was the Alcotts' second daughter. Her short story Transcendental Wild Oats tells about her experiences at Fruitlands.

- Charles Lane – Lane met Bronson Alcott in England in 1841. He lived at the Alcott House school there. His very strict ideas about living a "pure" life contributed to the community's end. His son also lived at Fruitlands.

- Joseph Palmer – Palmer joined Fruitlands in August 1843. He stayed until the community ended. Later, he bought the farm and started another unique society there. He was known for wearing a full beard, which was unusual at the time. He even went to prison for defending his right to wear it.

- Isaac Hecker – Hecker started as a baker in New York City. He then explored many religious and spiritual paths. He lived at Brook Farm, another Transcendentalist community, before coming to Fruitlands. He sought a "deeper" spiritual life at Fruitlands but only stayed for two months. He later became a Roman Catholic priest.

- Samuel Larned – Like Hecker, Larned briefly lived at Brook Farm before Fruitlands. He was known for using strong language. He believed that swears, if said with a pure heart, could inspire listeners.

- Abraham Everett – Also known as Abraham Woods, he changed his name to Wood Abram when he arrived at Fruitlands. He had faced personal challenges before joining Fruitlands.

- Samuel Bower – Bower lived at Fruitlands for only a few months.

- Ann Page – Besides Abby May Alcott, Page was the only other adult woman at Fruitlands. She and Mrs. Alcott did most of the household chores. They often had to work on the farm too. Page was eventually asked to leave Fruitlands. It is said this happened because she ate a piece of fish, which was forbidden.

Why Fruitlands Ended and Its Lasting Story

Farming was the biggest problem at Fruitlands. The community arrived at the farm a month late for planting. Only about 11 acres of land were suitable for growing crops. The decision not to use animals for farm work was a major reason for the community's failure. Also, many of the men spent their days teaching or discussing ideas instead of working in the fields. Using only their hands, the Fruitlands residents could not grow enough food to last through the winter.

Fruitlands also struggled because of its strict structure. Alcott and Lane had almost complete power. They set very strict rules for living. Alcott's wife, Abby May, wrote that she felt "almost suffocated in this atmosphere of restriction."

The Fruitlands experiment ended just seven months after it began. According to Bronson Alcott, the residents left in January 1844. His daughter, Louisa May, wrote that they left in December 1843, which is thought to be more accurate. Alcott was very sad about Fruitlands failing. He moved his family to live with a nearby farmer and refused to eat for several days. Later, Ralph Waldo Emerson helped the family buy a home in Concord.

Fruitlands had only a short time to influence America and the Transcendentalist movement. After it closed, one of its former members, Joseph Palmer, bought the land. For 20 years, he used the site as a safe place for other reformers. In 1910, Clara Endicott Sears bought the property. She opened the farmhouse to the public in 1914 as a museum. Today, the Fruitlands Museum also has a museum about Shaker life. It includes an art gallery with 19th-century paintings and a museum of Native American art and crafts.

See Also

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |