Brook Farm facts for kids

|

Brook Farm

|

|

|

|

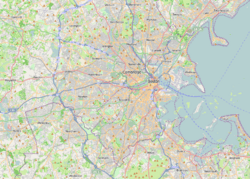

| Location | 670 Baker Street, Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Area | 188 acres (0.76 km2) |

| Built | 1841 |

| Architect | Brook Farm Community |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000141 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | July 23, 1965 |

Brook Farm was a special community in the United States during the 1840s. It was an experiment where people tried to live and work together, sharing everything. This idea is called a communal living or a utopian experiment, meaning they hoped to create a perfect society.

The community was started in 1841 by George Ripley, a former minister, and his wife Sophia Ripley. It was located on a farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, not far from Boston. Their ideas were partly inspired by transcendentalism, a way of thinking popular in New England that focused on individual freedom and the goodness of people and nature.

At Brook Farm, members believed that if everyone shared the work, they would have more time for fun, learning, and thinking. They hoped to balance hard work with plenty of time for reading, art, and discussions.

Life at Brook Farm was all about working together for the good of everyone. Each person could choose the work they liked best, and everyone, including women, was paid the same amount. The community earned money from farming, selling handmade items, and fees from visitors. The main way they made money was through their school, which was run by Mrs. Ripley. This school taught children from preschool to college prep, and even offered classes for adults.

However, Brook Farm always struggled with money. They found it hard to make enough profit from farming. In 1844, they tried a new plan based on the ideas of Charles Fourier, a socialist thinker. They even started building a large new building called the Phalanstery. Sadly, this building burned down before it was finished, and it wasn't insured. This financial disaster led to the community closing down by 1847.

Even though Brook Farm didn't last, many who lived there remembered their time fondly. Famous author Nathaniel Hawthorne was one of the first members. He later wrote about his experiences in his novel The Blithedale Romance (1852).

After Brook Farm closed, the land was used for many years by a Lutheran organization, first as an orphanage and then as a school. Today, much of the original farm is a historic site run by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation. It is recognized as a National Historic Landmark and a Boston Landmark.

Contents

How Brook Farm Began

Planning a New Community

In 1840, George Ripley told his friends in the Transcendental Club about his plan to start a special community. He called it Brook Farm. The main idea was that if people worked together and shared their labor, they would have more time for learning and creative activities.

Ripley believed this experiment would show the world a better way to live. He wanted to create a place with "industry without drudgery," meaning work that wasn't boring or tiring, and "true equality." Brook Farm was one of many similar communities in the United States during the 1840s, but it was the first one that wasn't based on a specific religion.

Starting the Farm

In 1841, George and Sophia Ripley, along with 10 other investors, created a company to buy a dairy farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. They sold shares in the company for $500 each. People who bought shares were promised a small part of any profits.

The farm was about 8 miles (13 km) from Boston. It was described as a beautiful place, close enough to the city but still peaceful. People started moving in by April 1841, and the farm was officially bought in October.

Many people were interested in joining. Famous writer Margaret Fuller often visited, though she never officially became a member. To join fully, people usually had to buy a $500 share in the company.

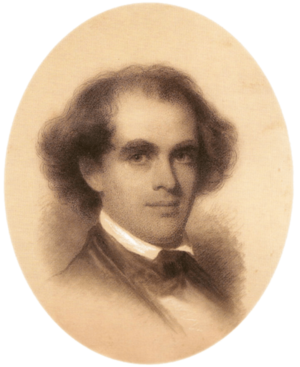

Nathaniel Hawthorne's Time at Brook Farm

One of the first members was the author Nathaniel Hawthorne. He didn't fully agree with the community's ideas. He mostly hoped to earn enough money to start his life with his future wife, Sophia Peabody.

Hawthorne found farm work very hard. He complained that he had "no quiet at all" and that his hands were covered in blisters from raking hay. He left Brook Farm in October 1842. He later wrote that even his old job at the Custom House felt freer than his time at the farm.

Changes and Challenges

New Ideas from Charles Fourier

In the late 1830s, George Ripley became very interested in the ideas of Charles Fourier. Fourier was a French thinker who had detailed plans for how an ideal community, which he called a "Phalanx," should be organized.

Many people, including newspaper editor Horace Greeley, encouraged Brook Farm to follow Fourier's ideas more closely. This happened when the community was already struggling to make enough money.

To follow Fourier's vision, Brook Farm changed its name to the "Brook Farm Association for Industry and Education." They began building a huge new communal building called the Phalanstery in 1844. This building was planned to house many families and single people, and include a large dining hall and lecture rooms.

Publishing The Harbinger

In 1844, Brook Farm members decided to take over two publications that promoted Fourier's ideas. They combined them into a new journal called The Harbinger. The first issue came out in June 1845. It was printed weekly at Brook Farm until 1847, helping the community become leaders in the Fourierism movement.

The End of Brook Farm

After changing to Fourier's system, Brook Farm began to decline quickly. Money problems continued, and they had to make sacrifices, like cutting back on food. In November 1845, there was even an outbreak of smallpox, though no one died.

Then, on March 3, 1846, disaster struck. The large Phalanstery building, which was still under construction, caught fire and burned down completely. The building was not insured, and the loss of $7,000 was a huge financial blow. This fire marked the beginning of the end for Brook Farm.

George Ripley, who started the community, left in May 1846. Many others also began to leave. To pay off debts, Ripley's personal book collection, which had been the farm's library, was sold at auction. By the end, Brook Farm owed over $17,000. Ripley took a job with a newspaper and spent 13 years paying off the community's debts.

What Happened After Brook Farm

In 1849, the land was sold. Later, during the American Civil War, it was used as a training camp for soldiers.

In 1870, a Lutheran organization bought the property. They opened an orphanage there in 1872, which operated until 1943. Later, it became a treatment center and school, closing in 1977. Most of the original buildings from the Transcendentalist era, like the Margaret Fuller Cottage, burned down over the years. The only remaining historic building today, a print shop, was built by the Lutherans around 1890.

In 1988, the State of Massachusetts bought 148 acres (0.6 km2) of the original land. Today, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation manages this part of Brook Farm as a historic site. It is a U.S. National Historic Landmark and a Boston Landmark, recognized for its important place in history.

Community Life

Work and Money

Members of Brook Farm were also shareholders. They were promised a small share of any yearly profits or free schooling for one student. In return, they agreed to work 300 days a year and received free room and board. Everyone, including women, was paid the same wages.

The main idea behind their work was to combine thinking and physical labor. Ripley believed that people should not just do manual work but also have time for intellectual pursuits.

At first, members could choose the work they liked best. However, some felt that not everyone was doing their fair share. So, in 1841, they set work standards: 10 hours a day in summer and 8 hours in winter. When they adopted Fourier's ideas, the work became more organized, with different groups for farming, mechanical tasks, and household duties. This new system actually helped Brook Farm make a profit in 1844, which was a rare achievement.

Typical jobs included chopping wood, milking cows, and other farm chores. Some members also worked as shoemakers or teachers. No matter the job, everyone was considered equal. In exchange for their work, members received medical care, education, and entertainment.

Many visitors came to Brook Farm, paying a fee to see how the community worked. Between 1844 and 1845, they collected over $400 from visitors.

Despite these efforts, the community was almost always in debt. The land was difficult to farm, and they didn't have enough workers. They often spent money before they had it.

Education at Brook Farm

The "Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and Education" was officially started in September 1841. The school was the community's most important source of income. It attracted students from far away, including places like Cuba and the Philippines.

Children under 12 were charged $3.50 per week. Older students paid $4 a week. Adult education was also offered in the evenings, with classes on topics like moral philosophy, German, and European history.

The school had an infant school for young children, a primary school, and a preparatory school for older students getting ready for college. Each younger student was assigned a woman from the community to help with their clothes and habits.

The teachers included graduates from Harvard Divinity School and several women. George Ripley taught English, and another teacher, Charles Dana, taught many languages. Students learned European languages, literature, and fine arts. The primary school used a modern teaching style that focused on the child. Sophia Ripley, George's wife, was very dedicated to the school, teaching history and foreign languages.

Fun and Free Time

Even though Brook Farm members spent a lot of time working and studying, they always made time for fun. They enjoyed music, dancing, card games, plays, costume parties, sledding, and skating. Every week, the community would gather for a dance.

At the end of each day, many members would join hands in a circle for a "symbol of Universal Unity," promising to be true to "God and Humanity."

People at Brook Farm generally stayed positive, even with money troubles. Having free time was a key part of Brook Farm's philosophy. As Elizabeth Palmer Peabody wrote in 1842, the community aimed to be rich "not in the metallic representative of wealth, but in ... leisure to live in all the faculties of the soul."

The Role of Women

At Brook Farm, women had more opportunities than in typical society at the time. Their work was highly valued. While they did traditional tasks like cooking and housekeeping, they also worked in the fields during harvest. Men even helped with laundry in cold weather.

Because the community didn't follow one strict religion, women were free from some of the traditional rules of the time. They could own shares in the company and make their own decisions. Women also helped earn money by making fancy caps, capes, and other items to sell in Boston shops. Others painted screens and lampshades.

Women were encouraged to go to school, and many female writers and performers visited because of Brook Farm's reputation for educating women. Sophia Ripley, who had written a strong essay about women's rights, was highly educated and taught history and foreign languages at the farm.

Brook Farm in Stories

Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the first members, was not happy during his time at Brook Farm. He found it hard to write there. He later used his experiences to create his 1852 novel, The Blithedale Romance.

In the book, a writer like Hawthorne visits a utopian community and finds that hard farm work makes it difficult to be creative. Hawthorne said that his novel was a "faint and not very faithful shadowing of Brook Farm." He also said that the characters in his book were not meant to represent any specific people from Brook Farm.

See also

In Spanish: Brook Farm para niños

In Spanish: Brook Farm para niños

- National Register of Historic Places listings in southern Boston, Massachusetts

- List of American utopian communities

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |