Horace Greeley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Horace Greeley

|

|

|---|---|

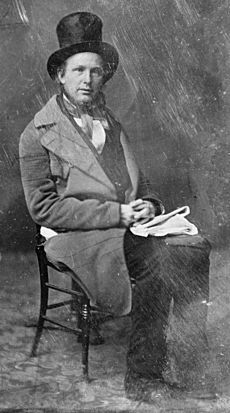

Greeley, c. 1860s

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 6th district |

|

| In office December 4, 1848 – March 3, 1849 |

|

| Preceded by | David S. Jackson |

| Succeeded by | James Brooks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 3, 1811 Amherst, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | November 29, 1872 (aged 61) Pleasantville, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Green-Wood Cemetery |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Mary Cheney

(m. 1836; died 1872) |

| Signature | |

Horace Greeley (born February 3, 1811 – died November 29, 1872) was a famous American newspaper editor and publisher. He started and edited the New-York Tribune newspaper.

Greeley was very active in politics. He served a short time as a congressman for New York. In 1872, he ran for president with the new Liberal Republican Party. However, he lost badly to the current president, Ulysses S. Grant.

Horace Greeley was born into a poor family in Amherst, New Hampshire. He became a printer's apprentice in Vermont. In 1831, he moved to New York City to start his career. He wrote for and edited several publications. He also got involved in the Whig Party. He played a big part in William Henry Harrison's successful presidential campaign in 1840.

The next year, Greeley started the Tribune. It became one of the most widely read newspapers in the country. This was thanks to its weekly editions sent by mail. He encouraged people to move to the American Old West. He saw it as a place full of chances for young and jobless people. He made the famous saying, "Go West, young man, and grow up with the country." He also supported many social reforms like socialism, vegetarianism, and temperance. He hired the best writers he could find for his newspaper.

Greeley's political friends helped him serve three months in the House of Representatives. There, he made many people angry by investigating Congress in his newspaper. In 1854, he helped create the Republican Party. Newspapers across the country often reprinted his articles. During the Civil War, he mostly supported President Abraham Lincoln. However, he wanted Lincoln to end slavery sooner than Lincoln was ready to.

After Lincoln's death, Greeley supported the Radical Republicans. They were against President Andrew Johnson. Later, Greeley disagreed with the Radicals and President Ulysses Grant. He felt there was too much corruption. He also believed that Reconstruction policies were no longer needed.

In 1872, Greeley became the presidential candidate for the new Liberal Republican Party. He lost by a lot, even with support from the Democratic Party. His wife died five days before the election, which greatly saddened him. He passed away a month later, before the Electoral College could officially vote.

Contents

Horace Greeley's Early Life

Horace Greeley was born on February 3, 1811, on a farm near Amherst, New Hampshire. He was a very smart student in school. Some neighbors offered to pay for him to go to a good school. But his family was too proud to accept help.

In 1820, his father lost money and moved the family to Vermont. They had to leave New Hampshire to avoid being jailed for debt. Even though his father struggled, Horace read every book he could find. In 1822, Horace tried to become a printer's apprentice. But he was told he was too young.

In 1826, at age 15, Greeley became a printer's apprentice. He worked for Amos Bliss, who edited the Northern Spectator newspaper in East Poultney, Vermont. He learned how to print and became known for knowing a lot. He read all the books in the local library. When the newspaper closed in 1830, he went to join his family in Pennsylvania. He worked briefly for the Erie Gazette before moving to New York City.

Starting His Own Publications

In late 1831, Greeley moved to New York City. He hoped to find success there. Many young printers were in the city, so he only found short jobs. In 1832, he worked for a publication called Spirit of the Times. He saved money and opened his own print shop that year.

In 1833, he tried to edit a daily newspaper, the New York Morning Post. But it did not do well and he lost money. Despite this, Greeley published the Constitutionalist three times a week. This paper mostly printed lottery results.

On March 22, 1834, he launched The New-Yorker with Jonas Winchester. It was cheaper than other magazines and included both poems and political comments. It became quite popular, but it was not managed well. It eventually failed because of a money crisis in 1837. Greeley also published a newspaper for the new Whig Party in New York. He came to believe in their ideas, like free markets and government help for national growth.

Greeley met Mary Young Cheney soon after moving to New York City. They both lived in a boarding house that followed a special diet. They avoided meat, alcohol, coffee, tea, and spices. Mary Cheney was a schoolteacher. They got married in Warrenton, North Carolina, on July 5, 1836. Greeley did not take a honeymoon. He went straight back to work, and his wife found a teaching job in New York City.

The New-Yorker suggested that jobless city people should move to the American West. In the 1830s, the "West" meant today's Midwestern states. A harsh winter and money problems in 1836–1837 left many New Yorkers homeless. Greeley wrote in his journal that new immigrants should buy guidebooks about the West. He also wanted Congress to make public lands cheap for settlers. He told his readers, "Go to the West: there your capabilities are sure to be appreciated and your energy and industry rewarded."

In 1838, Greeley met Thurlow Weed, an editor from Albany. Weed hired Greeley to edit the state Whig newspaper, the Jeffersonian. This paper helped elect the Whig candidate for governor, William H. Seward. In 1839, Greeley worked for several journals. He also took a month-long trip as far west as Detroit.

Greeley was very involved in the 1840 presidential campaign for William Henry Harrison. He published the main Whig newspaper, the Log Cabin. He also wrote many pro-Harrison songs that were sung at large meetings. These meetings were often organized by Greeley. His songs helped get Whig voters excited. Harrison and his running mate John Tyler won easily.

Editor of the Tribune

Starting the Newspaper (1841–1848)

After the 1840 campaign, the Log Cabin had 80,000 readers. Greeley decided to start a daily newspaper, the New-York Tribune. At that time, New York had many newspapers. James Gordon Bennett's New York Herald was the biggest.

Greeley borrowed money from friends to start his paper. The first issue of the Tribune came out on April 10, 1841. This was the day of a parade for President Harrison, who had died. In the first issue, Greeley promised his paper would be a "new morning Journal of Politics, Literature, and General Intelligence." At first, New Yorkers were not very interested. The paper cost one cent. It started with 600 subscribers and sold 5,000 copies of the first issue.

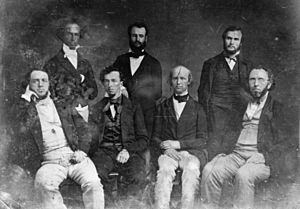

In the early days, Henry J. Raymond was Greeley's main helper. Raymond later started The New York Times. To make the Tribune financially strong, Greeley sold half of it to attorney Thomas McElrath. McElrath became the publisher and handled the business side. The Tribune supported Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky. Clay wanted to develop the country with his "American System."

Greeley was one of the first editors to have a full-time reporter in Washington, D.C. This helped make the Tribune a national newspaper. The Weekly Tribune was also important. It started in September 1841 when the Log Cabin and The New-Yorker combined. It cost $2 a year and was sent by mail across the United States. It was very popular in the Midwest.

Greeley opposed slavery as early as the late 1830s. He was against adding the slaveholding Republic of Texas to the U.S. In the 1840s, he spoke out more and more against slavery spreading.

Greeley hired Margaret Fuller in 1844 as the Tribune's first literary editor. She wrote over 200 articles for the paper. He also helped promote the work of writers like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Greeley was very excited about other social movements. He supported the ideas of Charles Fourier, a French thinker. Fourier suggested creating communities called "phalanxes." These communities would have people from different backgrounds working together. Greeley promoted Fourierism in the Tribune. He was even involved with two such communities, but they both failed.

Serving in Congress (1848–1849)

In November 1848, Congressman David S. Jackson was removed from office for election fraud. Greeley was chosen to run in the special election for the rest of Jackson's term. He easily won and took his seat in Congress in December 1848.

As a congressman for three months, Greeley tried to pass a "homestead act." This act would let settlers buy land cheaply if they improved it. He quickly became known for criticizing Congress. He pointed out which congressmen missed votes. He also questioned the job of the House Chaplain. This made him unpopular.

He angered his colleagues even more on December 22, 1848. The Tribune published proof that many congressmen were paid too much for travel. Greeley tried to pass a bill to fix this, but it failed. He felt so disliked that he wrote to a friend, saying he had "divided the House into two parties." One party wanted him gone, and the other wanted to help make it happen.

Greeley also tried to end flogging (whipping) in the Navy. He wanted to ban alcohol from Navy ships. He tried to change the name of the United States to "Columbia." He also wanted to end slavery in Washington, D.C., and raise taxes on imported goods. All these ideas failed. One important thing from his time in Congress was his friendship with Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln was also a Whig serving his only term in the House. Greeley's term ended on March 3, 1849. He went back to New York and the Tribune.

Growing Influence (1849–1860)

By the late 1840s, Greeley's Tribune was very successful in New York. Its weekly edition was also very important across the country. It was read in rural areas and small towns. One journalist said its influence in the Midwest was second only to the Bible. The Tribune could shape public opinion more effectively than the president.

The Tribune remained a Whig paper, but Greeley often took his own path. In 1848, he was slow to support the Whig presidential candidate, General Zachary Taylor. Taylor was from Louisiana and a hero of the Mexican–American War. Greeley was against the war and against slavery spreading into new lands. He worried Taylor would support slavery expansion.

In 1853, the Whig party was divided over slavery. Greeley printed an article saying the paper was no longer Whig and was nonpartisan. He was sure the paper would not lose readers. When Senator Stephen A. Douglas introduced his Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854, Greeley strongly fought against it. This act would let people in each territory decide if it would be slave or free. After it passed, fighting broke out in Kansas. Greeley helped send free-state settlers there and armed them.

By 1858, the Tribune had 300,000 subscribers through its weekly edition. It remained a leading American newspaper through the Civil War.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act helped destroy the Whig Party. But a new party, against the spread of slavery, had been discussed for years. Starting in 1853, Greeley helped found the Republican Party. He might have even given it its name. Greeley attended the first New York state Republican Convention in 1854. He was disappointed not to be nominated for governor.

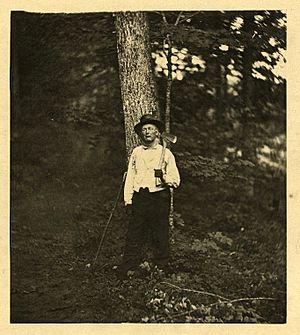

In 1853, Greeley bought a farm in Chappaqua, New York. He tried out new farming methods there. In 1856, he built Rehoboth, one of the first concrete buildings in the U.S.

The Tribune printed many different kinds of articles. In 1851, its managing editor, Charles A. Dana, hired Karl Marx as a foreign reporter in London. Marx wrote over 500 articles for the Tribune over ten years. Greeley also supported many reforms, like peace and women's rights. He especially promoted the idea of hard-working free laborers.

In 1859, Greeley traveled across the country to see the West. He wrote about it for the Tribune. He also spoke about the need for a transcontinental railroad. He visited Lawrence, Kansas, and then took a stagecoach to Denver. He sent reports back to the Tribune. He reached Salt Lake City and interviewed the Mormon leader Brigham Young. This was the first newspaper interview Young had given. Greeley met Native Americans and felt sympathy for them.

The 1860 Presidential Election

Greeley did not support Senator Seward for the Republican presidential nomination. Instead, he pushed for Edward Bates, a former Missouri representative. Bates was against the spread of slavery and had freed his own slaves. Greeley promoted Bates in his newspaper and speeches.

However, Abraham Lincoln came to New York to give a speech. Greeley encouraged his readers to go hear Lincoln speak. Greeley thought Lincoln might be a good candidate for vice president.

Greeley attended the Republican convention in Chicago. He promoted Bates but felt Seward would win. He told other delegates that Seward could not win important states like Pennsylvania. On the third vote, Lincoln was nominated. Greeley was seen smiling among the Oregon delegates.

Seward's supporters were angry at Greeley for Seward's loss. Greeley responded to attacks in his newspaper. He started a campaign against corruption in the New York Legislature. He hoped voters would elect new lawmakers who would then choose him for the Senate. (Before 1913, senators were chosen by state legislatures.) But his main goal in 1860 was to support Lincoln and criticize other candidates. He made it clear that a Republican government would not interfere with slavery where it already existed. He also said Lincoln was not in favor of voting rights for African Americans. Lincoln was elected in November.

Lincoln soon announced that Seward would be Secretary of State. This meant Seward would not run for re-election to the Senate. Greeley's supporters tried to get him elected to the Senate. But they did not have enough votes to win.

The Civil War Years

War Begins

After Lincoln was elected, some Southern states talked about leaving the Union. At first, the Tribune supported a peaceful separation. It suggested the South could become a separate nation.

But by January 1861, the Tribune changed its mind. Its articles took a strong stand against the South. They opposed any deals. Greeley briefly thought peaceful separation might be better than civil war. This idea was later used against him when he ran for president in 1872.

Before Lincoln's inauguration, the Tribune printed in large letters every day: "No compromise! No concession to traitors! The Constitution as it is!" Greeley attended the inauguration. When Southern forces attacked Fort Sumter, the Tribune was sad to lose the fort. But it was happy that war would now happen to stop the rebels, who formed the Confederate States of America. The paper criticized Lincoln for not acting quickly.

Through the spring and summer of 1861, Greeley and the Tribune pushed for a Union attack. "On to Richmond" became the newspaper's slogan. Greeley wanted the rebel capital of Richmond to be taken before the Confederate Congress met on July 20. Because of public pressure, Lincoln sent the Union Army into battle. They fought at the First Battle of Manassas in mid-July. The army was badly defeated. This defeat made Greeley very sad, and he might have had a nervous breakdown.

"The Prayer of Twenty Millions"

After two weeks at his farm, Greeley felt better. He returned to the Tribune and generally supported the Lincoln administration. He even said nice things about Secretary Seward, his old rival. He remained supportive even during the army's defeats in the first year of the war.

By early 1862, Greeley sometimes criticized the government again. He was frustrated by the lack of big military wins. He was also upset that Lincoln was slow to free the slaves once the Confederacy was defeated. The Tribune was pushing for this in its articles. This was a change for Greeley. After the First Battle of Manassas, he wanted the war to end slavery, not just save the Union.

Greeley's urging of Lincoln led to a letter on August 19, 1862. It was printed the next day in the Tribune as "The Prayer of Twenty Millions." By this time, Lincoln had already told his Cabinet about the Emancipation Proclamation he had written. Greeley was told about it the same day his "prayer" was printed. In his letter, Greeley demanded action on freeing slaves. He wanted strict enforcement of the Confiscation Acts.

Lincoln's reply became very famous. "My main goal in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery." Lincoln's statement angered those who wanted to end slavery. Greeley felt Lincoln had not truly answered him. But he said, "I'll forgive him everything if he'll issue the proclamation." When Lincoln did, on September 22, Greeley called the Emancipation Proclamation a "great gift of Freedom."

Draft Riots and Peace Efforts

After the Union victory at Gettysburg in July 1863, the Tribune wrote that the rebellion would soon be crushed. A week later, the New York City draft riots broke out. Greeley and the Tribune generally supported conscription (the draft). But they felt rich people should not be able to avoid it by hiring others to take their place.

Supporting the draft made them targets of the angry crowd. The Tribune Building was surrounded and even invaded. Greeley got weapons from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and 150 soldiers protected the building. Greeley's family was safe at their farm.

In August 1863, Greeley was asked to write a history of the war. He agreed and wrote a 600-page book called The American Conflict. It was very successful, selling 225,000 copies by 1870.

Throughout the war, Greeley thought about how to end it. In July 1864, he heard there were Confederate officials in Canada who wanted to talk peace. Lincoln asked Greeley to go to Niagara Falls, Canada. Lincoln was willing to consider any deal that included reuniting the country and freeing slaves. But the Confederates had no real power to make a deal. Greeley returned to New York, and the event embarrassed the government. Lincoln did not trust Greeley as much after this.

Greeley did not initially support Lincoln for re-election in 1864. He wrote that Lincoln could not win a second term. But no one else seriously challenged Lincoln. After Atlanta was captured by Union forces on September 3, Greeley became a strong supporter of Lincoln. He was happy about Lincoln's re-election and continued Union victories.

Reconstruction Era

As the war ended in April 1865, Greeley and the Tribune urged kindness towards the defeated Confederates. They argued that punishing Confederate leaders would only create more rebels. This talk of kindness stopped when Lincoln was killed. Many thought Lincoln's death was a final rebel plot. The new president, Andrew Johnson, offered a reward for the capture of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. After Davis was caught, Greeley first said he should be punished fairly.

By 1866, Greeley wrote that Davis, who was held at Fortress Monroe, should either be freed or put on trial. Davis's wife asked Greeley to help free her husband. In May 1867, a judge set bail for Davis at $100,000. Greeley was one of the people who signed the bail bond. This act made many people in the North angry at Greeley. Sales of his history book dropped sharply. Subscriptions to the Tribune also went down, but they recovered later.

Greeley first supported Andrew Johnson's easy Reconstruction policies. But he soon became disappointed. Johnson's plan allowed states to form new governments quickly without giving voting rights to freed slaves. When Congress took control of Reconstruction, Greeley generally supported them. Radical Republicans pushed for all men to have the right to vote and for civil rights for freed slaves. Greeley ran for Congress in 1866 but lost badly. He also ran for Senate in 1867 but lost.

Greeley remained strongly against President Johnson. When Johnson was impeached (accused of wrongdoing) in March 1868, Greeley and the Tribune strongly supported his removal. They called Johnson "an aching tooth in the national jaw." But the Senate found Johnson not guilty, which disappointed Greeley. In 1868, Greeley also tried to get the Republican nomination for governor but failed. He supported the successful Republican presidential candidate, General Ulysses S. Grant, in the 1868 election.

The Grant Years

In 1868, Whitelaw Reid joined the Tribune's staff as managing editor. Greeley found Reid to be a very reliable helper. Other famous writers like Mark Twain and John Hay also worked for the Tribune in the late 1860s. Greeley said Hay was the most brilliant writer for the Tribune.

Greeley remained interested in associationism. In 1869, he was involved in trying to start the Union Colony of Colorado. This was a planned community on the prairie, led by Nathan Meeker. The new town of Greeley, Colorado Territory was named after him. He helped fund the colony. In 1871, Greeley published a book called What I Know About Farming. It was based on his childhood and his experiences at his farm in Chappaqua.

Greeley kept trying to win political office. He ran for state comptroller in 1869 and for the House of Representatives in 1870, losing both times. In 1870, President Grant offered Greeley the job of minister to Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), but he said no.

Running for President in 1872

As was common in the 1800s, political parties often formed and disappeared. In September 1871, Senator Carl Schurz started the Liberal Republican Party. This party was against President Grant and corruption. They supported civil service reform, lower taxes, and land reform. The party needed a candidate for the upcoming presidential election. Greeley was one of the most famous Americans and often ran for office. He wanted to be president, either as a Republican or a Liberal Republican.

The Liberal Republican convention met in Cincinnati in May 1872. Greeley was considered a possible candidate. On the sixth vote, Greeley won the nomination, with Benjamin Gratz Brown as his running mate for vice president.

President Grant said about Greeley, "He is a genius without common sense."

The Democrats met in Baltimore in July. They had a tough choice: nominate Greeley, who had often been against them, or split the vote and lose to Grant. They chose Greeley and even adopted the Liberal Republican platform. This platform called for equal rights for African Americans.

Greeley quit as editor of the Tribune for the campaign. He went on a speaking tour to share his message, which was unusual for candidates at that time. He was criticized for actively campaigning. Greeley campaigned for peace between the North and South. He argued that the war was over and slavery was settled. It was time to return to normal and end the military presence in the South.

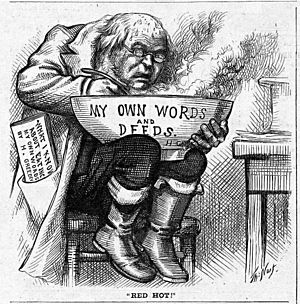

The Republicans ran a strong campaign against Greeley. They accused him of many things, from treason to supporting the Ku Klux Klan. The anti-Greeley campaign was famous for the cartoons by Thomas Nast. Nast's cartoons showed Greeley helping Jefferson Davis get bail. They also showed him throwing mud at Grant.

Greeley's wife Mary became very ill in October. He stopped campaigning after October 12 to be with her. She died on October 30, a week before the election. This made him very sad. The election results showed he would lose. He received 2,834,125 votes, while Grant got 3,597,132 votes. Grant won 286 electoral votes, and Greeley won 66. Greeley only won six states: Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee, and Texas.

Greeley's Final Month and Death

Greeley went back to editing the Tribune. But he soon learned there was a plan to remove him. He could not sleep. After his last visit to the Tribune on November 13 (a week after the election), he stayed under medical care. He was sent to a special house for care in Pleasantville, New York. He continued to get worse and died on November 29. His two daughters and Whitelaw Reid were with him.

His death happened before the Electoral College officially voted. His 66 electoral votes were split among four other people.

Greeley had asked for a simple funeral. But his daughters ignored his wishes. They arranged a grand funeral at the Church of the Divine Paternity, where Greeley was a member. He is buried in Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery. Many people attended, including old friends, Tribune employees, other journalists, and politicians like President Grant.

Horace Greeley's Legacy

Even though he was strongly criticized during the presidential campaign, many people were sad when Greeley died. Harper's Weekly wrote that his death was deeply regretted. Henry Ward Beecher wrote that "unjust and hard judgment of him died also." Harriet Beecher Stowe mentioned Greeley's unusual way of dressing. She said his "poor white hat" covered "much strength, much real kindness and benevolence."

Greeley supported policies that helped the growing western regions. He famously told people to "Go West, young man." He hired Karl Marx to cover working-class issues. He spoke out against monopolies (when one company controls everything). He also opposed giving land grants to railroads. He believed that industry would make everyone rich and supported high taxes on imported goods. He supported vegetarianism, was against alcohol, and paid attention to many different social ideas.

Greeley believed that everyone should have the chance to improve their lives.

However, Greeley's ability to bring about change was sometimes limited by his unique personality. He often looked like a farmer who had just come to town. He wore an old linen coat. He was also sometimes unaware of his own weaknesses.

The Tribune newspaper kept its name until 1924. Then it merged with the New York Herald to become the New York Herald-Tribune. This paper was published until 1966. The name lived on until 2013.

The town of Greeley, Colorado, is named after Horace Greeley.

There is a statue of Greeley in City Hall Park in New York. It was given by the Tribune Association. Another statue of Greeley is in Greeley Square in Midtown Manhattan. Greeley Square was named after him by the New York City Council after his death.

Books by Horace Greeley

- The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States of America, 1860–64 (Volume I: 1864, Volume II: 1866)

- Essays Designed to Elucidate The Science of Political Economy, While Serving To Explain and Defend The Policy of Protection to Home Industry, As a System of National Cooperation For True Elevation of Labor (1870)

- Recollections of a Busy Life (1868)

- Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859 (1860)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Horace Greeley para niños

In Spanish: Horace Greeley para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |