Radical Republicans facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Radical Republicans

|

|

|---|---|

| Leader(s) | • John C. Frémont • Benjamin Wade • Henry Winter Davis • Charles Sumner • Thaddeus Stevens • Hannibal Hamlin • Ulysses S. Grant • Schuyler Colfax |

| Founded | 1854 |

| Dissolved | 1877 |

| Succeeded by | certain factions became the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party |

| Ideology | Radicalism Abolitionism Reconstruction Unconditional unionism Developmentalism Free labor |

| National affiliation | Republican Party |

The Radical Republicans were a group of politicians within the Republican Party from 1854 to 1877. They were active before, during, and after the American Civil War. They called themselves "Radicals" because they wanted to make big, immediate changes. Their main goal was to end slavery completely and permanently.

After the Civil War, the Radicals worked to protect the rights of newly freed African Americans. They wanted to ensure that former slaves had the same rights as other citizens, including the right to vote. They often disagreed with more moderate politicians, including Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, who they felt were not doing enough to help.

The Radical Republicans were a powerful force during the period known as Reconstruction, when the country was rebuilding after the war. They helped pass important laws and constitutional amendments that changed American society.

Contents

Who Were the Radical Republicans?

The Radical Republicans believed that slavery was evil and that the Civil War was a chance to destroy it for good. Many were reformers who were inspired by their religious beliefs. They wanted to create a more equal and just nation.

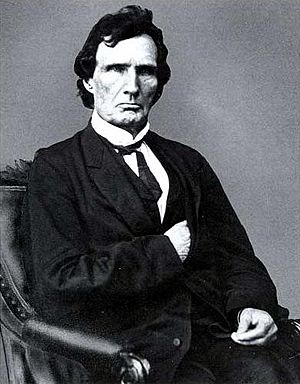

The term "Radical" was used before the Civil War to describe politicians in the North who were strongly against the power of slave owners. The group was never formally organized, but they shared common goals. Their most important leaders were Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts.

The Radicals were often opposed by Moderate Republicans, who wanted slower changes, and by the Democratic Party. However, for a time after the Civil War, the Radicals had enough power in the Congress to lead the effort of rebuilding the country.

The Radicals During the Civil War

During the Civil War, the Radical Republicans often criticized President Abraham Lincoln. They believed he was too slow in freeing the slaves and in allowing African American soldiers to fight for the Union. They pushed for a more aggressive war effort to defeat the Confederacy quickly and completely.

In 1864, the Radicals in Congress passed their own plan for Reconstruction, called the Wade–Davis Bill. This plan was much stricter on the Southern states than Lincoln's plan. Lincoln refused to sign the bill, which was a major disagreement between him and the Radicals. Despite their differences, Lincoln knew he needed the Radicals' support and appointed many of them to important positions in his government.

The Fight for Reconstruction

After the Civil War ended and Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, the country entered the Reconstruction era. This was the period of rebuilding the South and deciding how the defeated states would rejoin the Union. The Radical Republicans had very strong ideas about how this should be done.

Clashing with President Johnson

After Lincoln's death, Vice President Andrew Johnson became president. At first, the Radicals thought Johnson would support their goals. However, he soon became their biggest opponent. Johnson wanted to be lenient with the former Confederate states and did not support efforts to give civil rights to African Americans.

Johnson vetoed (rejected) several bills passed by Congress that were designed to protect the rights of freed slaves. This included the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The Radicals, however, had enough votes in Congress to override his vetoes. This was the first time in U.S. history that Congress passed a major law over a president's veto.

Taking Control of Congress

In the 1866 elections, voters in the North showed strong support for the Radical Republicans. They won a large majority in Congress, giving them the power to pass their own Reconstruction plans.

They passed the Reconstruction Acts, which placed the South under military rule. The new laws required Southern states to write new constitutions that guaranteed voting rights for African American men. Under these laws, former Confederate leaders were not allowed to vote or hold office. As a result, new governments were formed in the South made up of African Americans, white Southerners who supported Reconstruction (scalawags), and Northerners who had moved South (carpetbaggers).

Impeaching the President

The conflict between President Johnson and the Radical Republicans became so intense that the Radicals decided to remove him from office. The process for removing a president is called impeachment.

In 1868, the House of Representatives voted to impeach Johnson. He was accused of breaking the law by firing his Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, who was a supporter of the Radicals. The case then went to the Senate for a trial. The Senate needed a two-thirds vote to remove Johnson from office. In the end, the Radicals failed by just one vote, and Johnson remained president. However, he had lost most of his power.

President Grant and the End of an Era

In 1868, the war hero General Ulysses S. Grant was elected president. As a Republican, Grant generally supported the Radicals' goals for Reconstruction. He used the power of the federal government to protect the rights of African Americans in the South. He signed laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1871, which was used to fight against violent groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

However, by the 1870s, many people in the North were growing tired of Reconstruction. Some Republicans, who called themselves "Liberal Republicans", split from the party in 1872. They felt it was time to end the military presence in the South.

The end of Reconstruction came with the Compromise of 1877. In the very close presidential election of 1876, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was declared the winner. In exchange, he agreed to remove the last federal troops from the South. Without the army's protection, the remaining Republican governments in the South collapsed. This marked the end of the Radical Republican era.

Legacy of the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans had a lasting impact on the United States. Their greatest achievements were their contributions to three major amendments to the U.S. Constitution:

- The Thirteenth Amendment (1865), which abolished slavery.

- The Fourteenth Amendment (1868), which granted citizenship to all people born in the U.S. and guaranteed "equal protection of the laws."

- The Fifteenth Amendment (1870), which gave African American men the right to vote.

Although many of the rights they fought for were taken away from African Americans in the South after Reconstruction ended, these amendments remained part of the Constitution. They became the legal foundation for the Civil Rights Movement nearly a century later.

Key Radical Republican Leaders

- Thaddeus Stevens: A leader in the House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.

- Charles Sumner: A leading senator from Massachusetts.

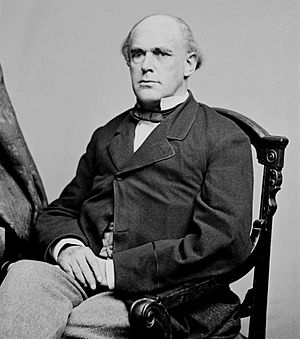

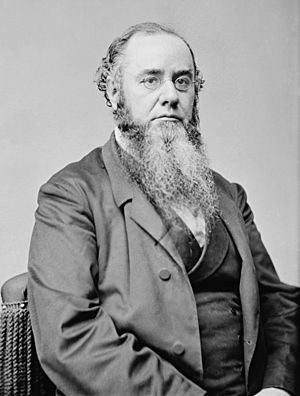

- Benjamin Wade: A senator from Ohio who would have become president if Johnson had been removed from office.

- Ulysses S. Grant: A general and later president who worked with the Radicals.

- Edwin M. Stanton: The Secretary of War under Lincoln and Johnson.

- Salmon P. Chase: The Secretary of the Treasury under Lincoln and later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

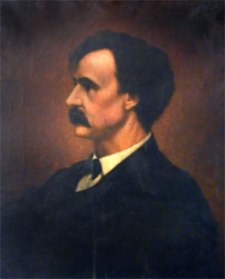

- Henry Winter Davis: A representative from Maryland.

- Benjamin Butler: A congressman from Massachusetts and a former Union general.

- John C. Frémont: An explorer and the first Republican candidate for president in 1856.

Images for kids