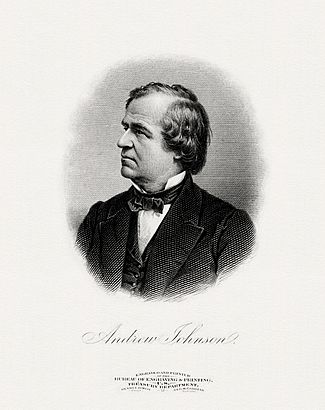

Edwin M. Stanton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

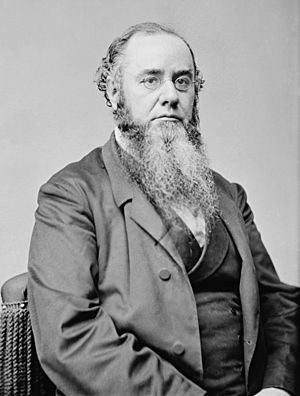

Edwin Stanton

|

|

|---|---|

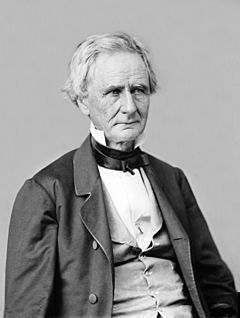

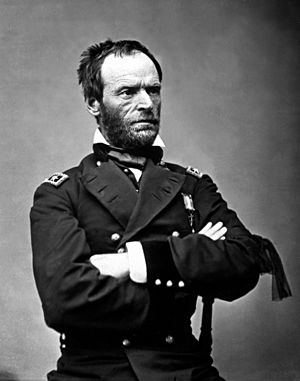

Photograph c. 1866-1869

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States-Designate | |

| In office Died before assuming office |

|

| Nominated by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | Robert Cooper Grier |

| Succeeded by | William Strong |

| 27th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office January 20, 1862 – May 28, 1868 |

|

| President | Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Simon Cameron |

| Succeeded by | John Schofield |

| 25th United States Attorney General | |

| In office December 20, 1860 – March 4, 1861 |

|

| President | James Buchanan |

| Preceded by | Jeremiah Black |

| Succeeded by | Edward Bates |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Edwin McMasters Stanton

December 19, 1814 Steubenville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | December 24, 1869 (aged 55) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Hill Cemetery, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1862) Republican (1862–1869) |

| Spouses |

Mary Lamson

(m. 1836–1844)Ellen Hutchison

(m. 1856) |

| Parents |

|

| Education | Kenyon College |

| Signature | |

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814 – December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician. He is best known for serving as the U.S. Secretary of War for President Abraham Lincoln during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's strong leadership helped organize the Union Army's huge resources. This guidance helped the North win the war. However, some generals thought he was too careful and tried to control too many small details. He also led the search for Lincoln's killer, John Wilkes Booth.

After Lincoln was assassinated, Stanton stayed on as Secretary of War under the new president, Andrew Johnson. This was during the first years of the Reconstruction Era. Stanton did not agree with Johnson's kind policies toward the former Confederate States. Johnson tried to fire Stanton, which eventually led to Johnson being impeached by the Radical Republicans in Congress. After leaving his role, Stanton returned to practicing law. In 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant nominated him to be a judge on the Supreme Court. Sadly, Stanton died just four days after the Senate approved his nomination. He is the only person approved for the Supreme Court who died before he could serve.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Growing Up in Ohio

Edwin McMasters Stanton was born on December 19, 1814, in Steubenville, Ohio. He was the first of four children born to David and Lucy Stanton. From a young age, Edwin loved books and poetry. He couldn't play many sports because he suffered from asthma, a breathing problem that bothered him his whole life.

When Edwin was 13, his father, a doctor, suddenly died. This left his family without much money. Edwin's mother opened a store to sell medical supplies and books. Edwin had to leave school and work at a local bookstore to help his family.

College and Law School

In 1831, Stanton started college at Kenyon College. He was very active in debates and discussions there. He had to leave college early because his family couldn't afford it anymore. After college, he worked in a bookstore in Columbus, Ohio, hoping to save money to finish his studies. When that didn't work out, he went back to Steubenville to study law.

In 1835, Stanton became a lawyer. He started working at a law firm in Cadiz, Ohio. He quickly became known for his skills in court.

First Marriage and Family Life

At 18, Stanton met Mary Ann Lamson. They married on December 31, 1836. His mother and sisters came to live with him and Mary in Cadiz. Stanton became an important person in the community. He worked with an anti-slavery group and wrote for a local newspaper. In 1837, he was elected the prosecutor for Harrison County.

Stanton and Mary had two children. Their daughter, Lucy Lamson, was born in 1840 but sadly died in 1841, just after her second birthday. Their son, Edwin Lamson, was born in 1842. In 1844, Mary Stanton became very sick and died. Stanton was heartbroken by her death.

After a time of deep sadness, Stanton focused on his legal cases. He became famous across the country for successfully defending a politician accused of stealing money. This case showed everyone how skilled he was as a lawyer. His law practice grew, and he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1847.

A Rising Lawyer (1839–1860)

Big Cases in Pittsburgh

In Pittsburgh, Stanton worked with other well-known lawyers. He handled several important cases. One famous case was about the Wheeling Suspension Bridge. This bridge was the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time. It connected the National Road but was too low for some ships to pass underneath. This caused problems for trade. Stanton argued in the United States Supreme Court that the bridge was blocking river traffic. He even showed how a ship's smokestack hit the bridge. The Supreme Court agreed and ordered the bridge to be raised. However, Congress later passed a law that allowed the bridge to stay as it was, which upset Stanton.

The McCormick Reaper Case

Stanton's success led him to another major case: McCormick v. Manny. This case was about the McCormick Reaper, a machine that harvested crops. Inventor Cyrus McCormick sued John Henry Manny, claiming Manny had copied his invention. Stanton joined Manny's legal team. The case was very important because it involved new technology and a lot of money. Stanton helped gather information and prepare the legal arguments. The court eventually ruled in favor of John Manny. This case further boosted Stanton's reputation as a top lawyer.

New Beginnings in Washington

In 1856, Stanton married Ellen Hutchinson. She came from a well-known family. They moved to Washington, D.C., where Stanton expected to do important legal work with the Supreme Court.

Stanton's friend, Jeremiah S. Black, became the United States Attorney General for President James Buchanan. Black asked Stanton to help with a huge land claim case in California. A man named Joseph Limantour claimed to own a large part of California, including much of San Francisco. The U.S. government believed his claims were fake.

Stanton agreed to take the case, even though his wife Ellen was not happy about him being so far away. He traveled to California with his young son, Eddie. Stanton worked for months, digging through old records from when California was part of Mexico. He found evidence that Limantour's claims were based on fake documents. In late 1858, Limantour's claims were denied, and he was arrested. Stanton's work saved a lot of land for the U.S. government. He returned home in early 1859, having proven himself a valuable lawyer for the government.

Joining President Buchanan's Cabinet (1860–1862)

A Nation Divided

In late 1860, the country was deeply divided over slavery and states' rights. Southern states were threatening to leave the Union. President Buchanan asked his Attorney General, Jeremiah Black, for advice on whether states could legally secede. Black, with Stanton's help, said that leaving the Union was illegal.

As states began to secede, Buchanan's cabinet was in chaos. Some members resigned because they thought the President was too weak. On December 20, 1860, Stanton was sworn in as Buchanan's new Attorney General. He found a cabinet that disagreed strongly on how to handle the crisis.

Stanton believed the Union must be defended. He and other cabinet members threatened to resign if President Buchanan ordered federal troops to leave Fort Sumter in South Carolina. Buchanan listened to them, and the troops stayed. However, South Carolina soon declared itself independent. By February 1861, six more Southern states had seceded.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln became president. Stanton, who had worked to keep Fort Sumter defended, felt a small hope that Lincoln would be strong against the South. Lincoln's speech said he would not allow states to leave the Union. Stanton was no longer Attorney General after Lincoln chose his own cabinet.

Advising the War Department

In July 1861, the North and South had their first big battle at Bull Run. The Union Army lost and retreated. Many Northerners realized the war would be much harder than they thought. The government needed more supplies for its growing army, but the War Department, led by Simon Cameron, was not handling things well. States were selling bad supplies at high prices.

Cameron asked Stanton to advise him on legal matters. Cameron was criticized for how he managed the department. He also caused controversy by suggesting that enslaved people should be armed to fight for the Union. Lincoln disagreed with this idea and ordered it removed from Cameron's official report.

Lincoln decided to replace Cameron. He nominated Stanton to be the new Secretary of War on January 13, 1862. The Senate approved him two days later.

Lincoln's Secretary of War (1862–1865)

Taking Charge

When Stanton became Secretary of War on January 20, 1862, the War Department was disorganized. Soldiers and government officials didn't respect it much. Stanton immediately started to fix things. He worked with Congress to remove people suspected of supporting the Confederacy. He also made big changes to how the department was run. He stopped the old system where military promotions were given based on favors, and instead, promotions were given based on merit.

Stanton also ordered that all military supplies must be bought from companies within the United States. This was a bold move, as it could have upset countries like Britain and France, who were looking for reasons to support the Confederacy. But Stanton insisted, and the order stayed.

He also created a better transportation and communication system for the North. He worked to control the railroads and telegraph lines, making sure the government could use them for war efforts. He moved the military's telegraph operations to his department, giving him more control over communications. He also controlled what information the press could report, to prevent leaks.

Stanton also took charge of the government's internal security. He continued the practice of arresting and holding people who were suspected of disloyalty, which was a controversial but necessary step during wartime.

Leading the Army

President Lincoln was frustrated with General George B. McClellan's slow actions. In March 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan as the overall commander of the Union Army, leaving him in charge only of the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln then gave Stanton more power over military decisions. This caused tension between Stanton and McClellan.

McClellan began his Peninsula Campaign to capture the Confederate capital, Richmond. Stanton wanted McClellan to attack quickly, but McClellan chose to lay siege to towns, which took a long time. Stanton also had to send some of McClellan's troops to defend Washington, D.C.

The campaign lasted for months. When Confederate General Robert E. Lee attacked, McClellan's army was pushed back. Stanton was blamed for McClellan's defeat by the public and the press. He had stopped military recruiting earlier, thinking the war would end quickly. When more soldiers were needed, he restarted recruiting, but the damage was done. Despite the criticism, Stanton stayed in his job at Lincoln's request.

Lincoln and Stanton decided the army needed a new overall commander. They chose General Henry W. Halleck. Later, after more Union defeats, Lincoln replaced McClellan with General Ambrose Burnside, and then with General Joseph Hooker. Stanton didn't like Hooker, but Lincoln chose him because he was known as a fighter.

Turning the Tide

In August 1862, General Lee defeated Union forces again at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Lee then moved his army into Maryland. Lincoln, without telling Stanton, put McClellan back in charge of a larger army. McClellan won a bloody victory at the Battle of Antietam, pushing Lee back into Virginia. McClellan then demanded more power and for Stanton to be removed, but Lincoln eventually fired him again.

The war continued with many battles. In 1863, General Hooker lost the Battle of Chancellorsville. Stanton tried to boost morale and improve discipline in the army. When Lee again pushed into the North, Hooker resigned. Lincoln and Stanton chose General George Meade to replace him.

Meade and Lee met at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. The Union won a great victory! Soon after, news came of General Ulysses S. Grant's victory at Vicksburg in the West. People in the North were overjoyed. Stanton even gave a rare speech to a cheering crowd.

In the West, Union forces faced a desperate situation at Chattanooga, Tennessee. Stanton secretly organized the transportation of thousands of Union troops by train to help. Lincoln and Stanton made General Grant the commander of almost all forces in the West. Grant, along with other generals, broke the Confederate siege at Chattanooga.

The War Ends

In 1864, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and became the overall commander of the Union Army. He began his push toward Richmond, clashing with Lee's army in fierce battles like the Battle of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania. Grant kept pushing forward, even with heavy losses. He then began the Siege of Petersburg, trapping Lee's army.

In the 1864 presidential election, Lincoln and his new Vice President, Andrew Johnson, won. Stanton played a big part in this victory. He ordered soldiers from key states to return home to vote. He also made sure Republican voters were not bothered at the polls.

On March 3, 1865, Grant told Washington that Lee wanted to discuss peace. Stanton insisted that only the President could make peace, not military generals. He told Grant to only discuss military surrender. Days later, Lincoln visited Grant. On April 1, General Philip Sheridan defeated Lee's army, forcing them to leave Petersburg. Stanton was thrilled and ordered flags to be put out.

News of Richmond's fall on April 3 caused huge celebrations in the North. Stanton was overjoyed, decorating the War Department with flags and giving an emotional speech. Lee's army finally surrendered on April 9, ending the war. Stanton immediately stopped conscription and army purchases.

Lincoln's Assassination

On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln invited Stanton and Grant to the theater, but they couldn't go. That night, Lincoln was shot at Ford's Theatre. Stanton quickly went to the scene. He found the dying President across the street at the Petersen House. While others were in shock, Stanton remained calm and took charge. He ordered guards for all cabinet members and the Vice President. He also ordered a lockdown of Washington, D.C., and called Grant back to the capital.

Andrew Johnson was sworn in as president the next day. Stanton, who had planned to retire, was now in control of the government because Johnson was new and unsure. Stanton ordered a search for the assassin, John Wilkes Booth, and his accomplices. He worked with the New York Police Department and War Department detectives. The conspirators were captured and tried. Booth was found and killed in Virginia. Stanton ordered Booth's body to be buried secretly to prevent him from becoming a hero to some.

Johnson Administration (1865–1868)

Sherman's Truce

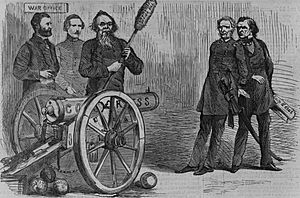

After the war, General William Tecumseh Sherman made a peace deal with a Confederate commander in North Carolina. However, Sherman was only allowed to discuss military matters, not political ones. His deal included recognizing Southern governments, restoring property rights, and pardoning rebels. This went far beyond his authority.

When Stanton heard the news, he was very upset. He called an emergency meeting of President Johnson's cabinet. Everyone agreed that Sherman's deal had to be rejected. Johnson ordered Stanton to tell Sherman that the deal was off and that fighting would restart if necessary. Grant was sent to take command of the troops in the South.

Stanton also told the press about Sherman's unauthorized deal. He explained why it was rejected and even suggested that Sherman had carelessly allowed Confederate leader Jefferson Davis to escape. This made Sherman furious. He felt Stanton had unfairly called him disloyal. Sherman refused to shake Stanton's hand at a big army parade in Washington, D.C., showing his anger publicly. Stanton considered resigning but stayed at the request of President Johnson and others.

Reconstruction and Conflict with Johnson

After the war, Stanton had the big job of reorganizing the U.S. military for peacetime. He also focused on rebuilding the Southern states. Stanton supported Lincoln's plans for Reconstruction, which included military governments to keep order in the South.

However, President Johnson and the Republican-controlled Congress had very different ideas about Reconstruction. Johnson wanted to be more lenient with the South, allowing states to rejoin the Union easily if they accepted the Thirteenth Amendment (which ended slavery). Radical Republicans in Congress, including Stanton, wanted stronger protections for African Americans, like voting rights. They also wanted to punish former Confederate leaders.

The conflict grew. Congress passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867. This law was designed to protect Stanton, making it illegal for the President to fire certain cabinet members without Senate approval. Johnson vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode his veto.

With this protection, Stanton openly opposed Johnson's policies. Johnson became very frustrated and wanted to remove Stanton. In August 1867, Johnson suspended Stanton from his position and gave the job to General Grant. Stanton reluctantly agreed.

Impeachment of President Johnson

On January 13, 1868, the Senate voted to put Stanton back in his job. Grant, fearing legal trouble, immediately gave the office back to Stanton. Stanton returned to the War Department, happy about the support he received for opposing Johnson.

Johnson, however, was determined to remove Stanton. On February 21, Johnson told Congress he was firing Stanton and appointing someone else temporarily. Stanton, encouraged by Republicans, refused to leave his office. Republicans in the Senate quickly declared Johnson's action illegal. In the House of Representatives, a motion was made to impeach Johnson. On February 24, Johnson was impeached (accused of wrongdoing) by the House.

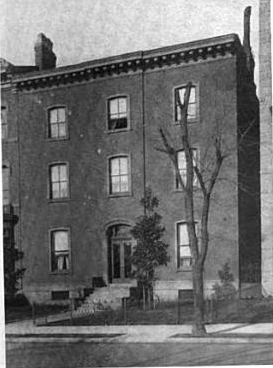

Johnson's trial began in the Senate in March. Many thought he would be removed from office because Republicans had a majority. Stanton stayed in the War Department headquarters for weeks. However, some senators began to hesitate. When the vote came, 35 senators voted to convict Johnson, and 19 voted to acquit him. This was one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed to remove him. Johnson was acquitted. On May 26, after Johnson was cleared of all charges, Stanton resigned.

Later Life and Legacy

After leaving office, Stanton continued to suffer from health problems, especially his asthma. He died on December 24, 1869, at his home in Washington, D.C. He was just 55 years old.

President Grant wanted a big state funeral for Stanton, but his wife, Ellen, preferred a simpler ceremony. Still, Grant ordered all public offices closed, and flags were lowered across the country. Many important officials, including President Grant, attended Stanton's funeral. He was buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Honors and Memorials

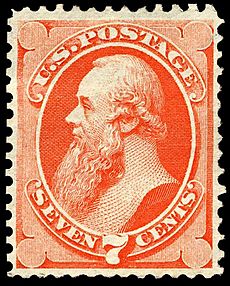

Edwin Stanton was one of the first Americans, other than a U.S. president, to appear on a U.S. postage stamp. His 7-cent stamp was issued on March 6, 1871.

His portrait also appeared on U.S. paper money in 1890 and 1891. These "treasury notes" are now rare and highly valued by collectors.

Many places are named after Edwin Stanton, including:

- Stanton Park in Washington, D.C.

- Stanton College Preparatory School in Jacksonville, Florida.

- Stanton County, Nebraska.

- Stanton Middle School in Hammondsville, Ohio.

- A neighborhood in Pittsburgh called Stanton Heights, with Stanton Avenue.

- Fort Stanton in Washington, D.C.

- Edwin Stanton Elementary School in Philadelphia.

- Stanton Street in Trenton, New Jersey.

- Edwin L. Stanton Elementary School in Washington, D.C., named for his son.

See also

In Spanish: Edwin M. Stanton para niños

In Spanish: Edwin M. Stanton para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |