Ambrose Burnside facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ambrose Burnside

|

|

|---|---|

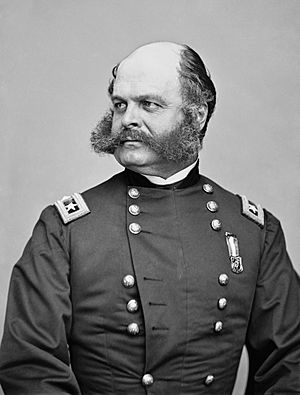

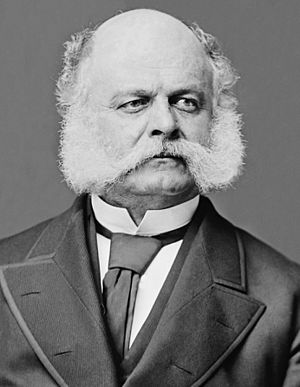

Burnside c. 1880

|

|

| United States Senator from Rhode Island |

|

| In office March 4, 1875 – September 13, 1881 |

|

| Preceded by | William Sprague IV |

| Succeeded by | Nelson W. Aldrich |

| 30th Governor of Rhode Island | |

| In office May 29, 1866 – May 25, 1869 |

|

| Lieutenant | William Greene Pardon Stevens |

| Preceded by | James Y. Smith |

| Succeeded by | Seth Padelford |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Ambrose Everett Burnside

May 23, 1824 Liberty, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | September 13, 1881 (aged 57) Bristol, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Angina |

| Resting place | Swan Point Cemetery Providence, Rhode Island |

| Political party | Democratic (1858–1865) Republican (1866–1881) |

| Spouse |

Mary Richmond Bishop

(m. 1852; |

| Education | United States Military Academy |

| Profession | Soldier, inventor, industrialist |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | Burn |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States (Union) |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1847–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Army of the Potomac Army of the Ohio |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

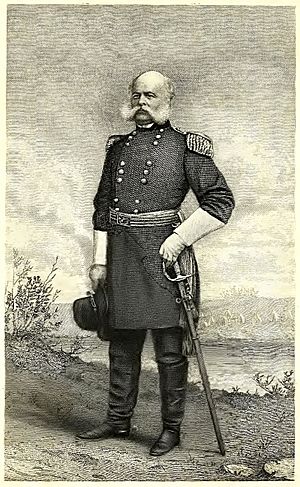

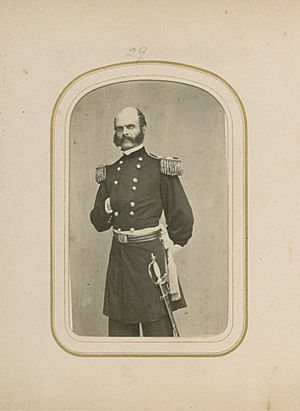

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American soldier and politician. He became a high-ranking general for the Union Army during the American Civil War. After the war, he served three terms as Governor of Rhode Island. He was also a successful inventor and businessman.

Burnside led some early Union victories. However, he was later promoted to roles that were perhaps too big for him. He is mainly remembered for two difficult defeats: at Fredericksburg and the Battle of the Crater near Petersburg. Even though an investigation cleared him for the second battle, he never fully regained trust as an army commander.

Burnside was a humble person who knew his own limits. He was pushed into high command even though he didn't want it. He often faced bad luck, both in battles and in business. For example, he lost the rights to a successful gun he had invented. His unique facial hair style, which connected his sideburns to his mustache, became known as "sideburns." This word came from his last name.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Burnside was born in Liberty, Indiana. He was the fourth of nine children. His family had roots in Ireland and England. His father, Edghill Burnside, freed his slaves when he moved to Indiana. Ambrose went to Liberty Seminary as a boy.

His schooling stopped when his mother died in 1841. He then became an apprentice to a local tailor. Eventually, he became a partner in the tailoring business.

Before the Civil War, Burnside was engaged to Charlotte "Lottie" Moon. She famously left him at the altar. Moon later became known for her work as a spy for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Early Military Career and Inventions

Burnside joined the United States Military Academy in 1843. He graduated in 1847, ranking 18th in his class. He became a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery. He went to Veracruz for the Mexican–American War. However, he arrived after the fighting had ended. He mostly performed guard duty around Mexico City.

After the war, Lieutenant Burnside served two years on the western frontier. He protected mail routes through Nevada to California. In 1849, he was wounded by an arrow during a fight with Apaches in Las Vegas, New Mexico. He was promoted to first lieutenant in 1851.

In 1852, he was stationed in Newport, Rhode Island. He married Mary Richmond Bishop of Providence, Rhode Island. Their marriage lasted until Mary's death in 1876. They did not have any children.

In 1853, Burnside left the regular U.S. Army. He was made commander of the Rhode Island state militia. He held this position for two years.

After leaving the Army, Burnside focused on making a new type of gun. This gun was called the Burnside carbine. The U.S. Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, agreed to buy many of these guns for the Army. Burnside built large factories to make them. However, another gunmaker reportedly bribed Floyd to cancel Burnside's contract.

Burnside ran for Congress in Rhode Island in 1858 as a Democrat. He lost the election by a lot. The costs of his campaign and a fire at his factory led to his financial ruin. He had to give up the rights to his gun patents. He then moved west to find work. He became the treasurer for the Illinois Central Railroad. There, he worked with and became friends with George B. McClellan. McClellan later became one of his commanding officers. Burnside also met Abraham Lincoln, who was a lawyer for the railroad and later became president.

Civil War Service

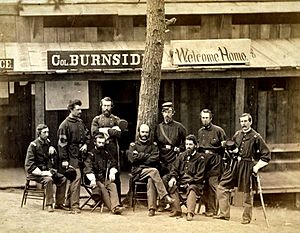

When the Civil War began, Burnside was a colonel in the Rhode Island Militia. He formed the 1st Rhode Island Infantry regiment. He was appointed its colonel in May 1861. Some of his regiment's soldiers used Burnside Carbines.

Within a month, he was given command of a brigade. He led this brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run in July. He then temporarily took over a division when its commander was wounded. His regiment's 90-day service ended in August. He was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers in August. He was then assigned to train new brigades for the Army of the Potomac.

North Carolina Campaign

From September 1861 to July 1862, Burnside led the Coast Division. This force later became the IX Corps. He led a successful water-based campaign in North Carolina. This campaign closed most of the North Carolina coast to Confederate ships for the rest of the war.

One important battle was the Battle of Elizabeth City in February 1862. Union Navy ships fought Confederate ships and a shore battery. The Union won, taking control of Elizabeth City and its waters. The Confederate fleet was captured or destroyed.

Burnside was promoted to major general of volunteers in March 1862. This was because of his victories at Roanoke Island and New Bern. These were the first major Union victories in the Eastern Theater. In July, his troops moved north and became the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

Burnside was offered command of the Army of the Potomac after General McClellan's failure in the Peninsula Campaign. He refused because he was loyal to McClellan. He also knew he lacked enough military experience for such a big role. He sent part of his corps to help General John Pope's army. Burnside again turned down command after Pope's defeat at Second Battle of Bull Run.

Antietam Battle

At the start of the Maryland Campaign, Burnside commanded the Right Wing of the Army of the Potomac. This included two corps. However, at the Battle of Antietam, McClellan split the corps. He placed them on opposite ends of the Union battle line. Burnside was put back in charge of only the IX Corps.

Burnside was slow to attack and cross what is now called Burnside's Bridge. He did not properly scout the area. He also missed easier places to cross the river. His troops had to make repeated attacks across the narrow bridge. Confederate sharpshooters on high ground controlled the bridge.

McClellan became impatient. He sent messengers to urge Burnside to move faster. The IX Corps finally broke through. But the delay allowed Confederate troops to arrive and push back the Union attack. McClellan refused Burnside's requests for more soldiers. The battle ended without a clear winner.

Fredericksburg Disaster

After McClellan failed to chase General Robert E. Lee's army, President Lincoln removed McClellan. On November 7, 1862, Lincoln chose Burnside to take command. Burnside reluctantly accepted. He did so partly because he was told that if he refused, the command would go to General Joseph Hooker, whom Burnside disliked. Burnside took charge of the Army of the Potomac on November 9, 1862.

President Lincoln wanted Burnside to act quickly. Burnside planned to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. This plan led to a terrible Union defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13. His army moved quickly to Fredericksburg. But the attack was delayed because engineers were slow to build floating bridges across the Rappahannock River. This allowed General Lee to gather his forces. Lee's troops easily stopped the Union attacks.

Attacks south of town were also poorly managed. These attacks were supposed to be the main effort. Initial Union breakthroughs were not supported. Burnside was very upset by his plan's failure. He was also distressed by the huge number of soldiers lost in his repeated, useless attacks. He offered to leave the U.S. Army, but his resignation was refused. Burnside's critics called him the "Butcher of Fredericksburg."

In January 1863, Burnside tried another attack against Lee. But it got stuck in winter rains. This event was mockingly called the Mud March. After this, he asked for several disobedient officers to be removed or tried by military court. He also offered to resign again. Lincoln quickly accepted this time. On January 26, Lincoln replaced Burnside with General Joseph Hooker.

East Tennessee Campaign

Burnside offered to resign from the army completely. But Lincoln said no, believing there was still a place for him. So, Burnside was put back in charge of the IX Corps. He was sent to command the Department of the Ohio. This area included Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. It was a quiet region with little fighting.

However, many people in these Western states were against the war. They had strong business ties with the South. Burnside was worried by this. He issued orders against "public sentiments against the war." This led to General Order No. 38. It said that anyone guilty of treason would be tried by a military court. They could be imprisoned or sent to enemy lines.

In May 1863, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham spoke out against the war. Burnside had him arrested for treason. A military court found Vallandigham guilty. He was sentenced to prison. Lincoln later ordered Vallandigham to be sent to Confederate territory instead. Lincoln also ordered a newspaper, the Chicago Times, to be reopened after Burnside had closed it. Lincoln warned generals not to arrest civilians or close newspapers without his permission.

Burnside also dealt with Confederate raiders like John Hunt Morgan.

In the Knoxville Campaign, Burnside moved to Knoxville, Tennessee. He took Knoxville without a fight. He then sent troops back to the Cumberland Gap. Confederate General John W. Frazer refused to surrender there. But Burnside arrived with more troops, forcing Frazer and 2,300 Confederates to surrender.

Confederate General James Longstreet chased Burnside. Burnside skillfully outmaneuvered Longstreet at the Battle of Campbell's Station. He reached his defenses in Knoxville safely. He was briefly surrounded there. But the Confederates were defeated at the Battle of Fort Sanders outside the city. Keeping Longstreet's troops busy at Knoxville helped General Ulysses S. Grant defeat General Braxton Bragg at Chattanooga. Union troops marched to help Burnside, but the siege was already over. Longstreet withdrew and returned to Virginia.

Overland Campaign and The Crater

Burnside's IX Corps was ordered back to the Eastern Theater. He built it up to over 21,000 soldiers. The IX Corps fought in the Overland Campaign in May 1864. It was an independent command at first, reporting directly to Grant. This was because Burnside outranked the Army of the Potomac's commander, General George Meade. This was changed in May. Burnside agreed to serve under Meade's direct command.

Burnside fought at the battles of Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House. He did not perform well, attacking in small groups. He seemed unwilling to fully commit his troops to the frontal assaults. After other battles, he took his place in the siege lines at Petersburg.

During the trench warfare at Petersburg in July 1864, Burnside agreed to a plan. A regiment of former coal miners in his corps suggested digging a tunnel under a Confederate fort. They would then explode it to create a breakthrough. The fort was destroyed on July 30 in the Battle of the Crater.

However, Meade interfered with the plan. Just hours before the attack, Burnside was ordered not to use his division of black soldiers. These troops had been specially trained for the assault. Instead, he had to use untrained white troops. He couldn't decide which division to use. So, his three commanders drew lots.

The division chosen was led by General James H. Ledlie. Ledlie failed to tell his men what to do. During the battle, he was reportedly hiding far behind the lines. Ledlie's men went into the huge crater instead of going around it. They got trapped and faced heavy fire from Confederates. This resulted in many casualties.

Burnside was removed from command on August 14. He was sent on "extended leave" by Grant. He was never called back to duty for the rest of the war. A later investigation blamed Burnside and his officers for the Crater disaster. Burnside finally resigned his commission on April 15, 1865.

The United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War later cleared Burnside. They blamed General Meade for making the specially trained black troops be removed.

After the War

After leaving the army, Burnside worked in many railroad and industrial leadership roles. He was president of several railroads. He also led the Rhode Island Locomotive Works.

He was elected Governor of Rhode Island three times. He served from May 29, 1866, to May 25, 1869. He was nominated by the Republican Party in March 1866. Burnside was elected governor by a large margin in April 1866. This started his political career as a Republican. He had been a Democrat before the war.

Burnside was a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. This was a society for Union officers. He was also commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) veterans' association from 1871 to 1872. In 1871, the National Rifle Association chose him as its first president.

During a trip to Europe in 1870, Burnside tried to help make peace between France and Germany in the Franco-Prussian War.

In 1874, Burnside was elected as a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island. He was re-elected in 1880. He served until his death in 1881. Burnside continued his work with the Republican Party. He played an important role in military matters. He also chaired the Foreign Relations Committee in 1881.

Death and Burial

Burnside died suddenly on September 13, 1881. He passed away from "neuralgia of the heart" (a type of chest pain called Angina pectoris) at his home in Bristol, Rhode Island.

Burnside's body was displayed at City Hall until his funeral on September 16. A procession took his casket to the First Congregational Church for services. Many important people attended. After the services, the procession went to Swan Point Cemetery for burial. Businesses and factories closed for much of the day. Thousands of mourners came from all over the state and nearby areas.

Legacy and "Sideburns"

Personally, Burnside was always very well-liked. He was popular in the army and in politics. He made friends easily, smiled often, and remembered everyone's name. However, his military reputation was not as good. He was known for being stubborn and not very creative. Many felt he was not suited for high command. Grant said he was "unfitted" to command an army. Burnside himself knew this best. He refused command of the Army of the Potomac twice. He only accepted the third time because he was told Joseph Hooker would get the command if he didn't.

Burnside was famous for his unusual beard style. He had strips of hair in front of his ears connected to his mustache, but his chin was clean-shaven. The word burnsides was first used to describe this style. Later, the syllables were switched around to give us the word sideburns.

Honors and Memorials

- In 1866, a township in Michigan was renamed Burnside Township to honor Ambrose Burnside.

- An equestrian statue of Burnside was placed in 1887 in Providence, Rhode Island. It was later moved to City Hall Park, which was renamed Burnside Park.

- Bristol, Rhode Island, has a small street named for Burnside.

- The Burnside Memorial Hall in Bristol, Rhode Island, is a public building. It was dedicated in 1883 by President Chester A. Arthur.

- Burnside, Kentucky, a small town, is named after the former site of Camp Burnside.

- New Burnside, Illinois, a village along a railroad line, was named after him because of his role in founding it.

- Burnside Residence Hall at the University of Rhode Island was opened in 1966.

- Burnside, Wisconsin is also named for the general.

Portrayals in Media

- Ambrose Burnside was played by Alex Hyde-White in the 2003 film Gods and Generals. This movie includes the Battle of Fredericksburg.

See also

In Spanish: Ambrose Burnside para niños

In Spanish: Ambrose Burnside para niños

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)