Battle of Cold Harbor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Cold Harbor |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

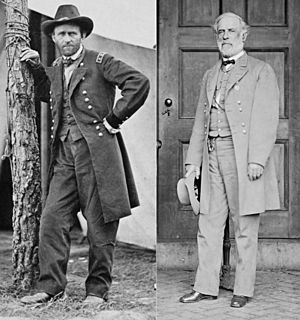

| Ulysses S. Grant George G. Meade |

Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Army of Northern Virginia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 108,000–117,000 | 59,000–62,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 12,738 total 1,845 killed 9,077 wounded 1,816 captured/missing |

5,287 total 788 killed 3,376 wounded 1,123 captured/missing |

||||||

The Battle of Cold Harbor was a major fight during the American Civil War. It happened near Mechanicsville, Virginia, from May 31 to June 12, 1864. The most intense fighting took place on June 3.

This battle was one of the last big fights in Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign. It is known as one of the bloodiest battles in American history. Thousands of Union soldiers were killed or hurt. They attacked strong defenses built by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's army.

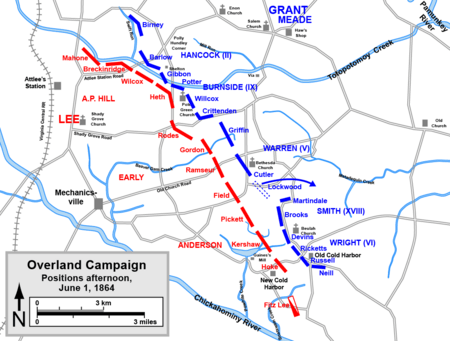

On May 31, Grant's army tried to go around Lee's army. Union cavalry took control of the Old Cold Harbor crossroads. This spot was about 10 miles northeast of Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. The Union cavalry held the crossroads until their main infantry arrived. Both Grant and Lee had lost many soldiers in earlier battles. They both received more troops to help them.

On the evening of June 1, Union troops attacked the Confederate defenses. They had some success. On June 2, the rest of both armies arrived. The Confederates built a long line of strong defenses, about 7 miles long. At dawn on June 3, three Union army groups attacked the southern part of these defenses. They were easily pushed back and lost many soldiers. Later attempts to attack were also unsuccessful.

Grant later said he always regretted the last attack at Cold Harbor. He felt no good came from the heavy losses. The armies stayed in their positions until June 12. Then, Grant moved his army again, heading toward the James River. Lee's army then dug in around Petersburg.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The War So Far

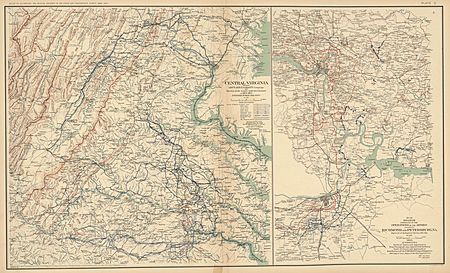

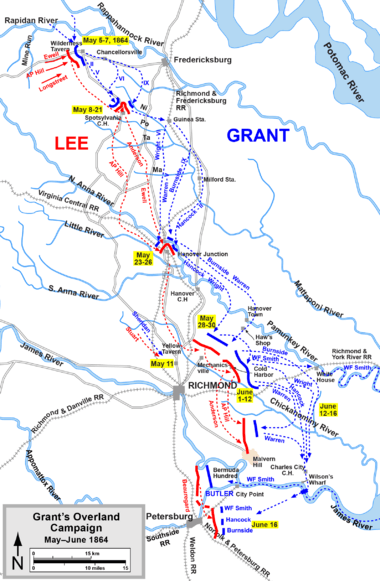

In May 1864, General Grant started a series of attacks against the Confederacy. Only two of these attacks were still moving forward. One was General William T. Sherman's attack on Atlanta. The other was Grant's own Overland Campaign. Grant was with the Army of the Potomac and its commander, General George G. Meade.

Grant's main goal was not to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. Instead, he wanted to destroy Lee's army. President Abraham Lincoln believed that if Lee's army was defeated, Richmond would fall anyway. Grant told Meade, "Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also." Grant hoped for a quick victory. But he was ready for a long war where both sides would lose many soldiers. The Union had more people and supplies to replace its losses.

On May 5, Grant's army crossed the Rapidan River. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia attacked them in a dense forest called the Wilderness. Lee's army was smaller, but they fought hard. After two days, both sides had lost many men. Neither side won a clear victory. Grant then moved his army around Lee's right side. He hoped to force Lee into another battle on better ground.

Lee's army quickly reached Spotsylvania Court House first. They started building trenches, which became very important for the smaller Confederate army. Grant kept trying to break Lee's lines at Spotsylvania. The fighting lasted from May 8 to May 21. It was very costly for both sides. Grant then decided to move his army again, around Lee's right side, toward Richmond.

Grant's next goal was the North Anna River. Lee's army got there first. On May 23, parts of Grant's army crossed the river. Lee then set up his army in a special "V" shape. He hoped to split Grant's army and defeat one part at a time. But Lee became sick and could not lead his attack. Grant realized the danger and ordered his men to stop advancing and build their own defenses.

Grant remained hopeful. He believed Lee's army was getting weaker. He wrote that he felt sure of victory.

Moving to Cold Harbor

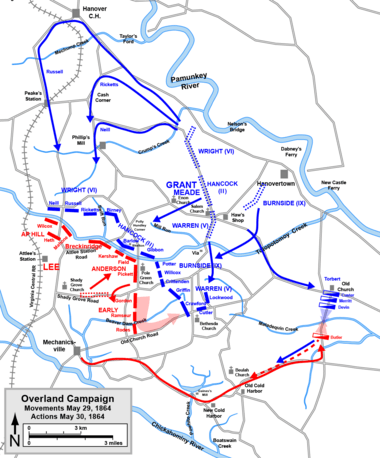

Grant then planned another big move around Lee's side. His army moved east of the Pamunkey River. Lee quickly moved his army to block Grant. He positioned his men behind a stream called Totopotomoy Creek. Lee wasn't sure of Grant's exact plans. He sent his cavalry to find out where Grant's main army was.

On May 28, Confederate cavalry fought Union cavalry at the Battle of Haw's Shop. It was a very bloody cavalry battle. Neither side won, but the Confederates learned where Grant's army was.

On May 30, Lee saw a chance to attack part of Grant's army. Confederate troops pushed back Union soldiers at the Battle of Bethesda Church. On the same day, a small cavalry fight at Matadequin Creek showed Lee that Grant was moving toward the crossroads of Old Cold Harbor. This was a very important spot.

Lee also learned that Grant was getting more soldiers. About 10,000 Union troops were coming from the Army of the James. These soldiers arrived on June 1. Lee also received reinforcements. Confederate President Jefferson Davis sent over 7,000 men from another area.

With these new troops, Lee's army had about 59,000 men. Grant's army had about 108,000 men. Grant's new soldiers were often new recruits. Lee's new soldiers were experienced veterans. They were also building very strong defenses.

Armies in the Battle

Union Forces

Grant's Union forces had about 108,000 soldiers. They included the Army of the Potomac and the XVIII Corps.

The main groups (corps) were led by:

- Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock (II Corps)

- Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren (V Corps)

- Brig. Gen. Horatio Wright (VI Corps)

- Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside (IX Corps)

- Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan (Cavalry Corps)

- Maj. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith (XVIII Corps)

Confederate Forces

Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had about 59,000 soldiers. It was organized into four corps and two other groups.

The main groups (corps) were led by:

- Lt. Gen. Richard H. Anderson (First Corps)

- Lt. Gen. Jubal Early (Second Corps)

- Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill (Third Corps)

- Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton (Cavalry Corps, after May 11)

- Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge (Breckinridge's Division)

- Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke (Hoke's Division)

Battle Location

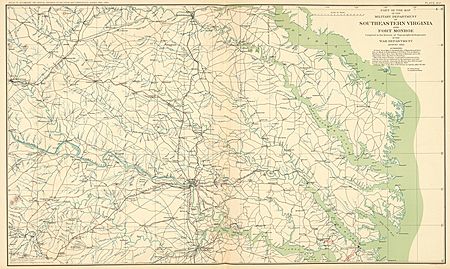

The battle took place in central Virginia. It was on the same ground as the Battle of Gaines's Mill in 1862. Some people call the 1862 battle the First Battle of Cold Harbor. They call the 1864 battle the Second Battle of Cold Harbor. Union soldiers digging trenches found bones from the first battle.

Cold Harbor was not a port city. It was named after two country crossroads. These crossroads had a tavern called the Cold Harbor Tavern. It offered shelter but no hot meals. Old Cold Harbor was two miles east of Gaines's Mill. New Cold Harbor was a mile southeast. Both were about 10 miles northeast of Richmond, the Confederate capital. From these crossroads, the Union army could get supplies and attack Richmond or Lee's army.

The Battle Unfolds

May 31: Cavalry Clash

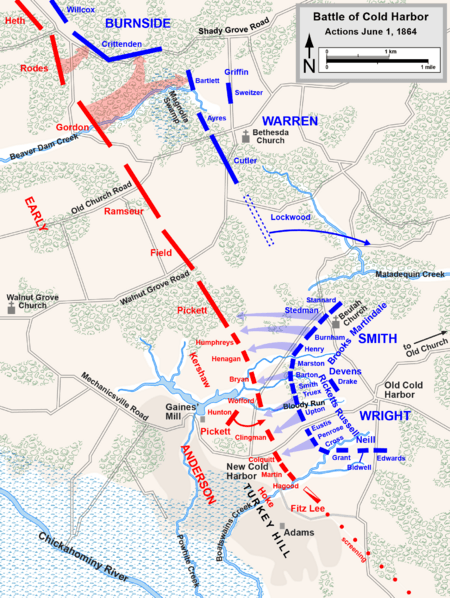

The cavalry forces that fought at Old Church continued to face each other. Lee sent more cavalry to help secure the crossroads at Old Cold Harbor. Union cavalry pushed the Confederates back from the crossroads. They started to dig in. As more Confederate troops arrived, the Union cavalry commander became worried. He ordered his men to pull back.

Grant still wanted Old Cold Harbor. He ordered more Union troops to move there. He told his cavalry to go back and hold the crossroads "at all hazards." The Union cavalry returned and found the Confederates had not noticed they had left.

June 1: First Infantry Attacks

Lee planned to attack the small Union cavalry forces at Old Cold Harbor. But his commanders did not work together well. Union troops were also disorganized. Some Union corps were marching slowly. One corps was sent to the wrong place.

Confederate troops attacked the Union cavalry. The Union cavalry had special repeating rifles. They fired many shots and caused heavy losses. The Confederate attack failed. By 9 a.m., more Union infantry arrived. They started to improve the trenches. Grant wanted them to attack right away. But the soldiers were tired from their long march. They also didn't know how strong the enemy was. The attack was delayed until the afternoon.

At 6:30 p.m., the Union attack finally began. Union troops moved forward. They faced heavy fire and made little progress. One Union officer described the Confederate fire as "A sheet of flame, sudden as lightning, red as blood." Some Union soldiers found a gap in the Confederate line. They charged through it. But they were surrounded and had to pull back. They did capture hundreds of prisoners.

Meanwhile, other Union corps were fighting on a different part of the line. Confederate troops attacked them. After some initial success, the Confederates were pushed back. By dark, the fighting stopped. The Union attack had cost 2,200 casualties. The Confederates lost about 1,800. Some Union generals were angry at Grant for ordering an attack without proper scouting.

June 2: Building Defenses

The Union attacks on June 1 had failed. But General Meade believed an early attack on June 2 could work. He and Grant decided to attack Lee's right side. They thought Lee's men would not have had time to build strong defenses there. If the attack worked, Lee's right flank would be pushed back toward the Chickahominy River.

Meade ordered a Union corps to move to the left of another corps. Once they were in position, Meade planned a big attack with three Union corps. This would be about 35,000 men. Meade also ordered other Union corps to attack Lee's left side. He thought Lee was moving troops from his left to his right.

Hancock's men marched all night. They were too tired to attack right away. Grant agreed to let them rest. He postponed the attack until 4:30 a.m. on June 3. But Grant and Meade did not give clear orders for the attack. They left it up to the corps commanders. No senior commander had checked the enemy's position closely. One Union general said he was "aghast" at the order. He felt it would be "simply an order to slaughter my best troops."

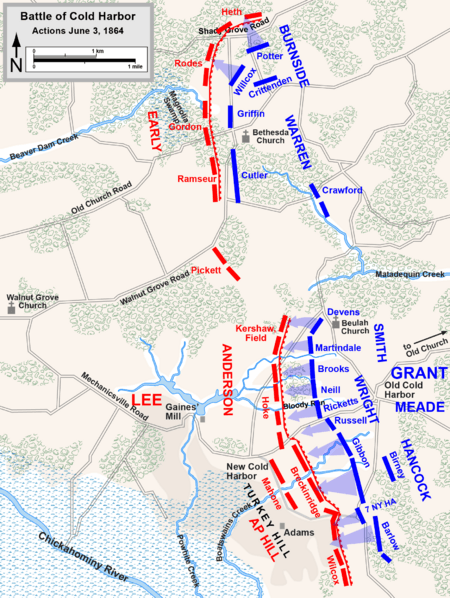

Lee used the Union delays to make his defenses even stronger. He moved more troops to his far right side. He also moved troops from another corps to support them. The result was a curving line of defenses, 7 miles long. It stretched from Totopotomoy Creek to the Chickahominy River. This made it impossible for the Union to go around Lee's army.

Lee's engineers built very clever defenses. They put up barricades of earth and logs. They placed artillery to fire on any approaching enemy. They even put stakes in the ground to help gunners aim. A newspaper writer said the defenses were "a maze and labyrinth of works within works." Confederate skirmishers hid the true strength of their lines.

Union soldiers knew what they were up against. Many had survived similar attacks before. One of Grant's aides said he saw many men writing their names on papers. They pinned these papers inside their uniforms. This was so their bodies could be identified if they were killed.

June 3: The Main Assault

At 4:30 a.m. on June 3, three Union corps began to advance. A thick fog covered the ground. Heavy fire from the Confederate lines quickly caused many casualties. The surviving Union soldiers were pinned down. The Union attack was pushed back. It resulted in some of the worst losses since the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862.

On the Union left, Hancock's corps had some success. They broke through part of the Confederate front line. They fought hand-to-hand and pushed the defenders out. They captured hundreds of prisoners and four cannons. But nearby Confederate artillery fired on them. The captured trenches became a death trap. Confederate reserves counterattacked and drove the Union soldiers back. One Union soldier complained about the lack of scouting. He wrote, "We felt it was murder, not war."

In the center, Wright's corps was pinned down by heavy fire. They made little effort to advance further. They were still recovering from their costly attack on June 1. The Confederate defenders in this area did not even realize a major attack had happened.

On the Union right, Smith's men advanced through difficult land. They were forced into two ravines. When they came out in front of the Confederate line, rifle and artillery fire cut them down. A Union officer wrote, "The men bent down as they pushed forward... and the files of men went down like rows of blocks." A Confederate described the artillery fire as "deadly, bloody work."

The only action on the northern end was by Burnside's corps. They launched a strong attack at 6 a.m. They pushed back the Confederate skirmishers. But Burnside mistakenly thought he had broken through the main defenses. He stopped his corps to regroup.

At 7 a.m., Grant told Meade to push any successful part of the attack. Meade ordered his three corps commanders to attack again. But they had all had enough. Hancock advised against it. Smith refused to attack again, calling it a "wanton waste of life." Wright's men increased their rifle fire but stayed in place. By 12:30 p.m., Grant accepted that his army was done. He wrote to Meade, "The opinion of the corps commanders not being sanguine of success... you may direct a suspension of further advance." Union soldiers still pinned down began digging their own trenches. They used cups and bayonets.

Meade later boasted about being in command. But his performance was poor. He failed to make sure his commanders scouted the ground. He also failed to properly lead the attack. Only about 20,000 of his men attacked. They paid a high price for the poorly planned assault. Estimates for Union casualties that morning range from 3,000 to 7,000. Confederate casualties were no more than 1,500.

Grant later said he always regretted the last attack at Cold Harbor. He felt no advantage was gained for the heavy losses. He noted that the Confederates seemed to regain hope after this attack. But this hope was short-lived.

June 4–12: Trench Warfare

Grant and Meade launched no more attacks on the Confederate defenses. The two armies faced each other for nine days. They fought in trenches, sometimes only yards apart. Sharpshooters constantly fired, killing many. Union artillery fired mortars. Confederates responded with their own artillery. Even without big attacks, the total casualties for the battle were twice as high as from the June 3 assault alone.

The trenches were hot, dusty, and uncomfortable. Conditions were even worse between the lines. Thousands of wounded Union soldiers suffered without food, water, or medical help. Grant did not want to ask for a formal truce. He felt that would be admitting he lost the battle. He and Lee exchanged notes for days. But they could not agree. When Grant finally asked for a two-hour stop to fighting, it was too late for most of the wounded. Grant was criticized for this in the Northern newspapers.

Grant realized he was in a stalemate with Lee again. He knew more attacks would not work. He planned three new actions. First, he hoped Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley would cut off Lee's supplies. This would force Lee to send troops there. Second, on June 7, Grant sent his cavalry to destroy a railroad near Charlottesville. Third, he planned to secretly move his army away from Lee's front. He would cross the James River.

Lee reacted as Grant hoped to the first two actions. He sent troops to the Valley to stop the Union forces. He also sent two of his three cavalry groups after the Union cavalry. However, Lee was surprised when Grant moved his army across the James River. On June 12, the Union army finally left Cold Harbor. They marched southeast to cross the James River and threaten Petersburg. Petersburg was a very important railroad hub south of Richmond.

Aftermath of the Battle

The Battle of Cold Harbor was the last major victory for Lee's army in the war. It was also his most decisive victory in terms of casualties. The Union army lost between 10,000 and 13,000 men over twelve days. This brought the total Union casualties since early May to over 52,000. Lee's army lost about 33,000 men. Even though Grant had huge losses, his larger army ended the campaign with fewer relative casualties than Lee's.

The battle made many people in the Northern states against the war. Grant became known as the "fumbling butcher" because of his bad decisions. It also made his soldiers feel less hopeful. But the campaign served Grant's purpose. Lee had lost the ability to attack. He was forced to focus on defending Richmond and Petersburg. Lee reached Petersburg just before Grant. He spent the rest of the war defending Richmond from behind strong trenches. Southerners knew their situation was serious. But they hoped Lee's strong defense would make Abraham Lincoln lose the 1864 presidential election. They hoped a new president would make peace. But when Atlanta was captured in September, these hopes ended. The end of the Confederacy was then only a matter of time.

Historic Buildings

During the battle, Burnett's tavern was used as a hospital. Union soldiers took everything valuable from it. Only a crystal bowl was saved by Mrs. Burnett. The Garthright House was also used as a field hospital. Its outside is still preserved today.

Battlefield Preservation

In 2008, the Civil War Trust said the Cold Harbor battlefield was one of the ten most endangered battlefields. New buildings were being built in the Richmond area. Only about 300 acres of the battlefield are saved today. The original battlefield was at least 7,500 acres. Part of it is now preserved as the Richmond National Battlefield Park. Hanover County also has a small 50-acre park next to the preserved area. The Trust and its partners have saved 250 acres of the battlefield by late 2021.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Cold Harbor para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Cold Harbor para niños