Jefferson Davis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jefferson Davis

|

|

|---|---|

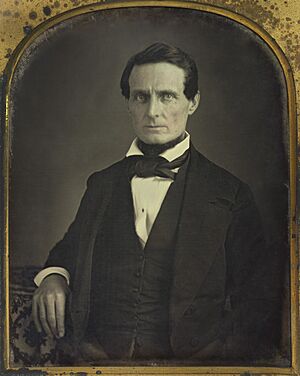

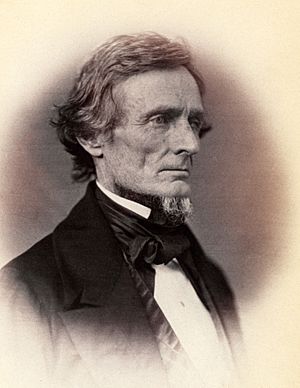

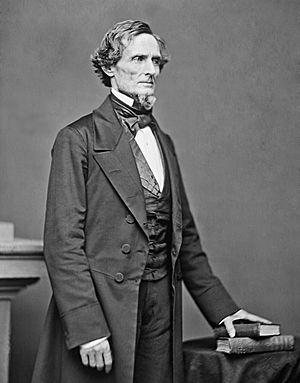

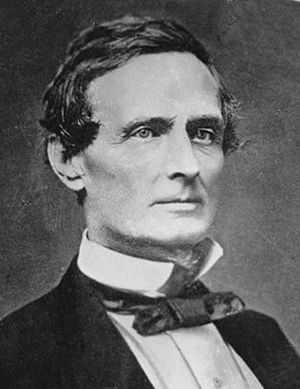

Portrait c. 1859

|

|

| President of the Confederate States | |

| In office February 22, 1862 – May 5, 1865 Provisional: February 18, 1861 – February 22, 1862 |

|

| Vice President | Alexander H. Stephens |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| United States Senator from Mississippi |

|

| In office March 4, 1857 – January 21, 1861 |

|

| Preceded by | Stephen Adams |

| Succeeded by | Adelbert Ames (1870) |

| In office August 10, 1847 – September 23, 1851 |

|

| Preceded by | Jesse Speight |

| Succeeded by | John J. McRae |

| 23rd United States Secretary of War | |

| In office March 7, 1853 – March 4, 1857 |

|

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Charles Conrad |

| Succeeded by | John B. Floyd |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Mississippi's at-large district |

|

| In office December 8, 1845 – October 28, 1846 Seat D |

|

| Preceded by | Tilghman Tucker |

| Succeeded by | Henry T. Ellett |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Jefferson F. Davis

June 3, 1808 Fairview, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | December 6, 1889 (aged 81) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hollywood Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations |

Southern Rights |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 6, including Varina |

| Education | United States Military Academy |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States Mississippi |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Unit | 1st U.S. Dragoons |

| Commands | 1st Mississippi Rifles |

| Battles/wars | |

Jefferson F. Davis (born June 3, 1808 – died December 6, 1889) was a key figure in American history. He served as the only president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. Before this, he represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives. He was also the 23rd Secretary of War for the United States.

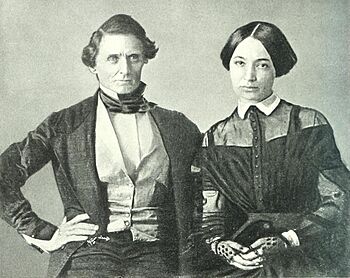

Davis was born in Fairview, Kentucky, and grew up in Mississippi. He attended the United States Military Academy at West Point and served as an officer in the United States Army. After leaving the army, he became a cotton planter and owned enslaved people. He married Sarah Knox Taylor, who sadly passed away shortly after their wedding. Later, he married Varina Howell.

He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and fought in the Mexican–American War. He then served in the U.S. Senate and as Secretary of War. In 1861, Mississippi left the United States, and Davis resigned from the Senate.

During the American Civil War, Davis led the Confederacy. After the Confederacy was defeated in 1865, he was captured and held in prison. He was released after two years without a trial. For many years, especially in the Southern United States, he was seen as a hero. However, in recent times, his role as a leader of the Confederacy and his support for slavery have led to much criticism. Many monuments dedicated to him have been removed.

Contents

- Jefferson Davis: A Leader in a Divided Nation

- Early Life and Education

- Life as a Planter and First Marriage

- Early Steps in Politics and Second Marriage

- Serving in the Mexican-American War

- Senator and Secretary of War

- President of the Confederate States

- After the War: Imprisonment and Release

- Later Years and Writings

- Death and Legacy

- Views on Slavery

- How He Led as Commander-in-Chief

- Books

- See also

Jefferson Davis: A Leader in a Divided Nation

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Mississippi

Jefferson F. Davis was the youngest of ten children born to Jane and Samuel Emory Davis. His family had roots in Wales and Scotland. His father, Samuel, fought in the American Revolutionary War. Jefferson was born on June 3, 1808, in Fairview, Kentucky. He was named after President Thomas Jefferson.

When Jefferson was young, his family moved to a farm near Woodville, Mississippi. There, his father grew cotton and owned enslaved people. Jefferson started school locally and later attended a Catholic preparatory school in Kentucky. He also studied at Jefferson College and Wilkinson Academy in Mississippi. In 1823, he went to Transylvania University in Kentucky. His father passed away in 1824, and his older brother, Joseph, became like a father figure to him.

Military Training at West Point

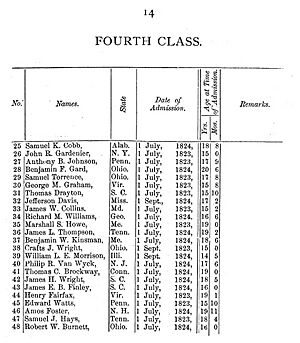

In 1824, his brother Joseph helped Jefferson get into the United States Military Academy at West Point. There, he became friends with future generals Albert Sidney Johnston and Leonidas Polk. Davis sometimes got into trouble for breaking academy rules. He graduated 23rd in his class.

After graduating, Davis became a Second Lieutenant in the United States Army. He served at different forts, including under Colonel Zachary Taylor, who would later become a U.S. President. Davis often faced health problems, especially during cold winters. He participated in the Black Hawk War and was known for treating the captured leader, Black Hawk, with kindness.

Davis fell in love with Colonel Taylor's daughter, Sarah. Colonel Taylor did not approve of their marriage. In 1835, Davis resigned from the army.

Life as a Planter and First Marriage

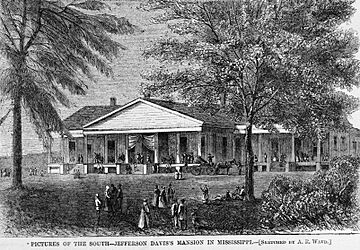

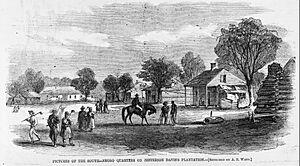

Davis decided to become a cotton planter in Mississippi. His brother Joseph helped him start Brierfield Plantation. Davis bought enslaved people to work on his land. By 1860, he owned 113 enslaved individuals.

He and Sarah Taylor married on June 17, 1835. Sadly, just three months later, Sarah became very ill with malaria and passed away at age 21.

For several years after Sarah's death, Davis focused on developing his plantation. He continued to learn about politics, law, and economics by reading books from his brother's large library. During this time, he became more involved in politics, with his brother's guidance.

Early Steps in Politics and Second Marriage

Davis became active in the Democratic Party in Mississippi in the early 1840s. In 1844, he met Varina Banks Howell, who was 18 years old. They became engaged quickly, despite her parents' concerns about their age difference and his political views.

Davis campaigned for the Democratic Party, supporting Southern interests like adding Texas to the United States. He and Varina married on February 26, 1845. They had six children, though four of them passed away at a young age.

In July 1845, Davis was elected to the United States House of Representatives. He believed in a strict interpretation of the Constitution and supported states' rights. He voted for the war with Mexico in May 1846.

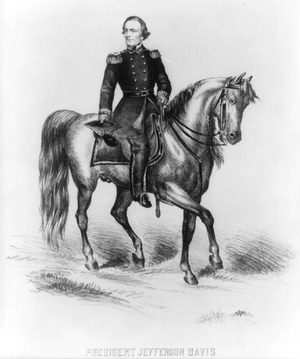

Serving in the Mexican-American War

When the Mexican-American War began, Davis joined a volunteer unit from Mississippi, the First Mississippi Regiment. He was chosen as its colonel. He made sure his regiment was equipped with new, advanced rifles, which became known as the "Mississippi rifle".

Davis's regiment served under his former father-in-law, Zachary Taylor. Davis showed bravery in battles like the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846. He resigned from the House of Representatives during this time. He also fought in the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, where he was wounded. President Polk offered him a promotion to general, but Davis declined. Instead, he accepted an appointment to fill a vacant seat in the U.S. Senate.

Senator and Secretary of War

Representing Mississippi in the Senate

Davis took his seat in the Senate in December 1847. He quickly became a strong supporter of allowing slavery to expand into new U.S. territories. He argued that slave owners should have the same right to settle in these territories as any other citizens. He opposed the Compromise of 1850, believing it would put Southern states at a disadvantage.

In 1851, Davis ran for governor of Mississippi but lost the election. He then spent some time at his plantation, remaining active in politics.

Leading the War Department

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce appointed Davis as his Secretary of War. In this role, Davis supported building a transcontinental railroad to the Pacific Ocean. He also promoted the Gadsden Purchase of land from Mexico, partly to help with a southern route for the railroad. He worked to improve the U.S. Army, increasing its size and pay, and shifting weapon production from muskets to rifles.

Davis helped pass the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854. This law allowed residents of the new Kansas and Nebraska territories to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. This decision led to increased conflict and violence in Kansas.

After President Pierce's term ended in 1857, Davis returned to the Senate. In the same year, the United States Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott case that slavery could not be banned from any U.S. territory.

Return to the Senate and Secession

Back in the Senate, Davis supported the Lecompton Constitution, which would have allowed Kansas to enter the Union as a slave state. However, it was not approved.

In 1858, Davis gave speeches in the North, talking about the shared history of Americans and the importance of the Constitution. He also stated that if an anti-slavery president were elected, Southern states might need to leave the Union to protect their way of life.

In February 1860, Davis proposed resolutions stating that Americans had a constitutional right to bring enslaved people into U.S. territories. The Democratic Party split over these issues, leading to Abraham Lincoln winning the 1860 presidential election. Davis advised caution, but South Carolina left the Union in December 1860. Mississippi followed on January 9, 1861. Davis resigned from the Senate, calling it "the saddest day of my life."

President of the Confederate States

Becoming President of the Confederacy

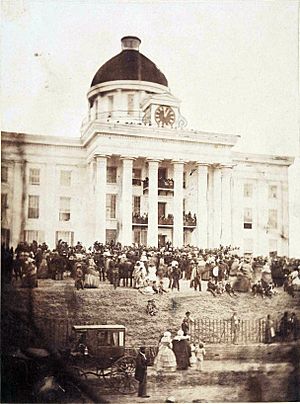

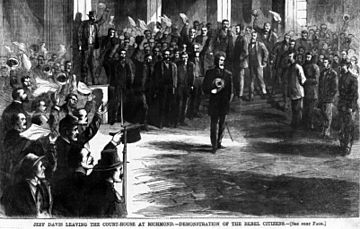

After Mississippi left the Union, Davis was appointed a major general in Mississippi's army. On February 9, 1861, he was unanimously elected as the provisional president of the Confederacy by a convention in Montgomery, Alabama. He was chosen for his political experience and military background. Davis had hoped for a military command, but he fully accepted his new role. He was inaugurated on February 18.

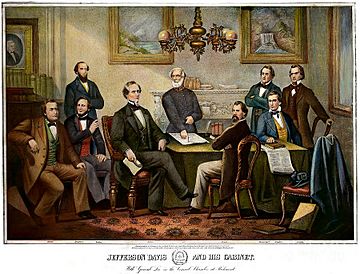

Davis formed his cabinet with members from different Confederate states. On November 6, 1861, he was elected president for a six-year term and took office on February 22, 1862.

Leading During the Civil War (1861-1865)

The Start of the War (1861)

As Southern states left the Union, they took control of most federal facilities. However, some forts, like Fort Sumter in South Carolina, remained under Union control. Davis wanted to avoid conflict to give the Confederacy time to prepare. When President Lincoln announced plans to resupply Fort Sumter, Davis ordered its surrender or attack. The fort's commander refused, and the attack on Fort Sumter began on April 12. After a long bombardment, the fort surrendered.

Lincoln then called for soldiers to put down the rebellion, which led four more states—Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas—to join the Confederacy. The Civil War had officially begun.

Davis was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate military. Major fighting began in Virginia in July 1861, where Confederate forces won the Battle of Manassas. In the West, a Confederate general violated Kentucky's neutrality, causing the state to seek help from the Union. This was a loss for the Confederacy.

Key Battles and Challenges (1862)

In February 1862, Union forces captured important forts in the West, leading to the loss of Kentucky, Nashville, and Memphis for the Confederacy. Davis focused on gathering troops for an offensive. Confederate forces attacked Union troops at the Battle of Shiloh in April, but the attack failed, and a key Confederate general was killed.

On February 22, Davis was formally inaugurated as president. He appointed General Robert E. Lee as his military advisor, and they developed a close working relationship. In the East, Union troops advanced toward the Confederate capital of Richmond. Lee took command of the Confederate army and pushed the Union forces back in the Seven Days Battles. Lee also won the Battle of Second Manassas in August. He then invaded Maryland but retreated after a difficult battle at Antietam in September.

In the West, Confederate General Bragg launched an offensive into Kentucky, but it failed due to a lack of coordination. Bragg was later defeated at the Battle of Stones River. Davis reorganized the command in the West, placing Joseph Johnston in overall charge.

Turning Points (1863)

On January 1, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared many enslaved people in Confederate states to be free. Davis saw this as an attempt to destroy the South.

In May, Lee won the Battle of Chancellorsville and then invaded Pennsylvania. Davis approved, hoping a victory in Union territory would help the Confederacy gain independence. However, Lee's army was defeated at the Battle of Gettysburg in July.

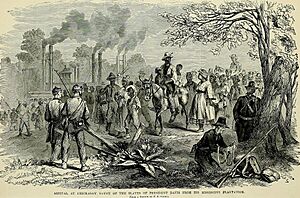

In April, Union forces attacked Vicksburg, Mississippi. After a long siege, the city surrendered on July 4. This loss gave the Union control of the Mississippi River. Davis's own plantation, Brierfield, was occupied, and his enslaved people gained their freedom.

Confederate General Bragg's army was pushed out of Chattanooga, Tennessee, but later won the Battle of Chickamauga. However, Union forces counterattacked and Bragg's army retreated. Davis replaced Bragg with Joseph Johnston.

During this time, people in Confederate cities faced food shortages and high prices, leading to protests. Davis traveled across the South to encourage people and military leaders.

The Final Years of the War (1864-1865)

In 1864, Davis's strategy was to exhaust the Union's will to fight, hoping they would elect a president who would make peace. Union armies advanced toward Atlanta, Georgia. Davis replaced General Johnston with General John B. Hood, but Hood's efforts did not stop the Union army, and Atlanta fell in September. Union forces then marched to Savannah and into South Carolina.

In Virginia, Lee's army fought a strong defense but eventually settled into trench warfare around Petersburg for nine months. In February 1865, Davis made Lee the general-in-chief of all Confederate armies. Davis also sent envoys for peace talks, but Lincoln would not consider an independent Confederacy.

Davis also considered allowing African Americans to earn their freedom by serving in the military. Congress passed a law supporting this, but it came too late to affect the war's outcome.

End of the Confederacy and Capture

In late March 1865, Union forces broke through Confederate lines, forcing Lee to abandon Richmond. Davis and his cabinet escaped by train. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9. Davis still wanted to continue the fight, but his generals told him they no longer had enough forces.

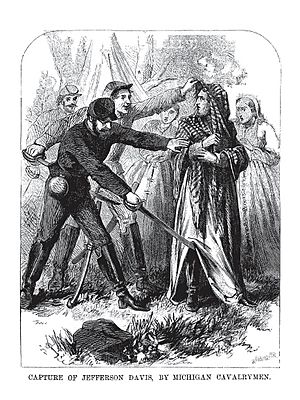

After President Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, the Union government believed Davis was involved and offered a reward for his capture. On May 5, Davis officially dissolved the Confederate government. On May 9, Union soldiers found and captured Davis near Irwinville, Georgia.

Confederate Policies During the War

National Decisions

Davis's main goal during the war was to achieve independence for the Confederacy. The Confederate government had to quickly create an army, navy, treasury, and other government structures.

Although Davis supported states' rights, he believed the Confederate Constitution allowed him to centralize power to fight the war. He worked with Congress to bring state military facilities under Confederate control. When soldiers were unwilling to re-enlist, Davis started the first conscription (draft) in American history. He also had the power to suspend certain legal protections when needed. These policies sometimes made him unpopular with state leaders who felt he was creating a government similar to the one they had left.

International Relations

Davis's foreign policy aimed to gain recognition from other countries. He hoped this would lead to international loans, trade, and possibly military alliances. Davis believed that European countries, which depended on Southern cotton, would quickly support the Confederacy.

However, despite the high demand for cotton, European nations did not officially recognize the Confederate States. They found new sources for cotton, and by the end of the war, no foreign country had recognized the Confederacy.

Managing Money During Wartime

Davis did not focus much on creating the financial system for the Confederacy, leaving most of it to his Secretary of the Treasury. The government struggled to raise money, partly because it could not collect export taxes on cotton due to the Union blockade.

Congress avoided unpopular taxes on land and enslaved people, which made up most of the South's wealth. Instead, the government printed a lot of money to fund the war, which caused the value of Confederate currency to drop dramatically. By 1865, the government relied on taking supplies from people to support the military.

After the War: Imprisonment and Release

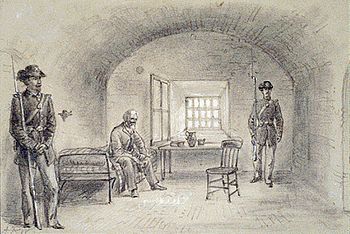

On May 22, 1865, Davis was imprisoned at Fort Monroe, Virginia. Initially, he was kept in a small room, had guards constantly watching him, and was not allowed contact with his family. Over time, his treatment improved. After public concern, his restraints were removed, and he was allowed to read and exercise. His wife, Varina, was later allowed to visit him regularly.

President Andrew Johnson's cabinet considered trying Davis for serious accusations related to the war, like being involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln or how prisoners were treated. However, they could not find enough reliable evidence to link him directly to these claims. They decided it would be best to try him for disloyalty to the country in a civil court case.

After two years in prison, Davis was released on May 13, 1867, after prominent citizens paid his bail. He then moved to Canada and later to England with his family. Davis remained accused of disloyalty until President Johnson issued a pardon for all participants in the rebellion in December 1868. Davis's case never went to trial.

Later Years and Writings

Finding a New Path

After his release, Davis faced financial difficulties. He turned down some job offers, not wanting to harm institutions while he was still under accusation. He traveled to Britain and France looking for business opportunities but found none. In 1869, he became president of the Carolina Life Insurance Company in Tennessee.

Davis often received invitations to speak. In 1870, he gave a speech honoring Robert E. Lee. He also became a member of the Southern Historical Society, which focused on explaining the Civil War from the Southern perspective.

The company he led faced problems, and Davis resigned in 1873. He continued to look for ways to earn a living, including investments in railroads and other businesses. He also worked to reclaim his Brierfield Plantation, eventually regaining legal ownership in 1881.

Sharing His Story

In 1877, author Sarah Dorsey invited Davis to live at her estate, Beauvoir, in Mississippi, and begin writing his memoirs. His wife, Varina, later joined him and helped with his writing. Dorsey passed away in 1879 and left Beauvoir to Davis.

Davis's first book, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, was published in 1881. It aimed to explain his actions during the war and argue for the right of states to leave the Union. He also wrote A Short History of the Confederate States of America.

In 1886, Davis toured the South, attending events and giving speeches. Large crowds came to see him, solidifying his image as an important figure in the South. His last tour was in 1887, where he met with Confederate veterans.

Death and Legacy

His Final Days

In November 1889, Davis became ill during a steamboat trip to his plantation. He was diagnosed with acute bronchitis and malaria. He passed away on December 6, 1889, in New Orleans, at the age of 81, surrounded by family and friends.

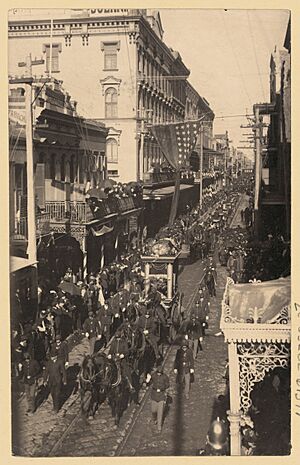

Remembering Jefferson Davis

Davis's funeral was one of the largest ever held in the South, with over 200,000 mourners attending. He was buried in New Orleans, but his wife later decided he should be reburied in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, alongside other Confederate figures. His remains were moved in 1893, with many stops along the way where people paid their respects.

Although Davis served the United States in various roles, his legacy is mainly defined by his leadership of the Confederacy. After the Civil War, some blamed him for the Confederacy's defeat. However, after his release from prison, he became a respected figure in the white South. His birthday became a legal holiday in several Southern states, and many monuments were dedicated to him.

In 1978, Davis's U.S. citizenship was restored after the Senate passed a resolution. President Jimmy Carter described this as an act of reconciliation. However, Davis's legacy continues to be debated. In the 21st century, many historians view his role in the Confederacy as an act of disloyalty to the United States. His memorials have been criticized for supporting beliefs that one race is superior to others, and many have been removed, including statues in Texas, New Orleans, Memphis, and Kentucky. Following events related to racial justice in May 2020, protesters removed Davis's statue in Richmond, Virginia. The city council later funded the removal of its pedestal.

Views on Slavery

During his time as a senator, Davis strongly supported the right of Southern states to have slavery. He argued that the Constitution recognized the right of states to allow citizens to own enslaved people as property. He believed the federal government should protect this right.

In his speeches, Davis stated that enslaved people should be allowed in federal territories. He claimed that slavery was supported by religion and history. He also argued that it brought economic and social benefits to everyone.

After Mississippi left the Union, Davis's speeches acknowledged the connection between the Confederacy and slavery. In his resignation speech from the Senate, he mentioned that the idea of "all men are created free and equal" was being used to attack the South's social institutions. In his inaugural speech as provisional president, he said the Confederate Constitution, which protected slavery, was a return to the original intentions of the nation's founders. He later stated that the war was caused by Northerners who wanted to end slavery, which would destroy millions of dollars worth of Southern property. In 1863, he criticized the Emancipation Proclamation, calling it an attempt to abolish slavery and harm African Americans.

How He Led as Commander-in-Chief

Davis felt confident in his military skills because he had graduated from West Point and served in the army. He actively managed the Confederacy's military policies, working long hours on organization, finances, and logistics for the armies.

Some historians believe Davis's personality contributed to the Confederacy's defeat. They suggest he focused too much on small military details and struggled to delegate tasks. He has also been criticized for sometimes choosing generals who did not meet expectations or for keeping generals in command for too long. His desire to always be seen as right may have created problems with politicians and generals he relied on.

However, other historians point out his strengths. Davis quickly organized the Confederacy despite its focus on states' rights, and he remained focused on gaining independence. He was a skilled speaker who tried to promote national unity. His policies helped the Confederate armies continue fighting for a long time, keeping Southern hopes alive and challenging the North's will to continue the war. Some historians argue that Davis was one of the best leaders available for the role and that his strategies helped the Confederacy last as long as it did.

Books

- The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government [2 Volumes]

- A Short History of the Confederate States of America

- The Papers of Jefferson Davis

See also

In Spanish: Jefferson Davis para niños

In Spanish: Jefferson Davis para niños