Alexander H. Stephens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander H. Stephens

|

|

|---|---|

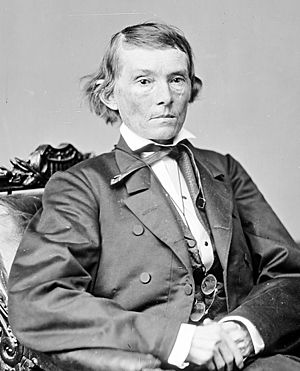

Portrait by Mathew Brady, c. 1860s

|

|

| 50th Governor of Georgia | |

| In office November 4, 1882 – March 4, 1883 |

|

| Preceded by | Alfred H. Colquitt |

| Succeeded by | James S. Boynton |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia |

|

| In office December 1, 1873 – November 4, 1882 |

|

| Preceded by | John James Jones |

| Succeeded by | Seaborn Reese |

| Constituency | 8th district |

| In office October 2, 1843 – March 3, 1859 |

|

| Preceded by | Mark Anthony Cooper |

| Succeeded by | John James Jones |

| Constituency | At-large (1843–1845) 7th district (1845–1853) 8th district (1853–1859) |

| Vice President of the Confederate States | |

| In office February 22, 1862 – May 11, 1865 Acting: February 11, 1861 – February 22, 1862 |

|

| President | Jefferson Davis |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Member of the Confederate States Provisional Congress from Georgia |

|

| In office February 4, 1861 – February 17, 1862 |

|

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Member of the Georgia Senate from the Taliaferro County district |

|

| In office November 7, 1842 – December 27, 1842 |

|

| Preceded by | Singleton Harris |

| Succeeded by | Abner Darden |

| Member of the Georgia House of Representatives from the Taliaferro County district |

|

| In office November 7, 1836 – December 9, 1841 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 11, 1812 Crawfordville, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | March 4, 1883 (aged 71) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | A. H. Stephens State Park, Crawfordville |

| Political party | Whig (1836–1851) Unionist (1851–1860) Constitutional Union (1860–1861) Democratic (1861–1883) |

| Education | University of Georgia (BA) |

| Signature | |

Alexander Hamilton Stephens (February 11, 1812 – March 4, 1883) was an important American politician. He served as the Vice President of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. Later, he became the 50th Governor of Georgia from 1882 until his death. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Georgia in the United States House of Representatives both before and after the Civil War.

Stephens went to Franklin College and became a lawyer in his hometown of Crawfordville, Georgia. After serving in the Georgia state government, he was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1843. He became a key Southern Whig and was against the Mexican–American War. After the war, Stephens supported the Compromise of 1850. He also helped create the Georgia Platform, which was against states leaving the Union.

Stephens supported allowing slavery to expand into new territories. He helped pass the Kansas–Nebraska Act. As the Whig Party faded, Stephens joined the Democratic Party. He worked with President James Buchanan to try and make Kansas a state that allowed slavery, but voters there rejected it.

Stephens chose not to run for re-election in 1858. He continued to speak out against states leaving the Union. However, after Georgia and other Southern states formed the Confederate States of America, Stephens was elected as their Vice President. In his Cornerstone Speech in March 1861, he defended slavery. He explained the Confederacy's reasons for leaving the Union. During the war, he often disagreed with President Jefferson Davis's decisions. He especially disliked the Confederate draft and the suspension of habeas corpus. In February 1865, he met with Abraham Lincoln to discuss peace, but they could not agree.

After the war, Stephens was held in prison until October 1865. The next year, Georgia elected him to the United States Senate. However, the Senate did not allow him to join because of his role in the Civil War. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1873. He served there until 1882, when he became Governor of Georgia. Stephens died in March 1883, just four months after becoming governor.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Alexander Stephens was born on February 11, 1812. His parents were Andrew Baskins Stephens and Margaret Grier. They lived on a farm near Crawfordville, Georgia. Alexander's mother died when he was only three months old. In 1814, his father married Matilda Lindsay.

In May 1826, when Alexander was 14, both his father and stepmother died from pneumonia. This meant Alexander and his siblings had to live with different relatives. He grew up in tough conditions and was poor. Alexander went to live with his mother's brother, General Aaron W. Grier. General Grier had a large library, and Alexander loved to read.

Alexander was often sick but was very smart. He got his education thanks to several helpful people. One was a minister named Alexander Hamilton Webster. Stephens admired him so much that he took Webster's middle name, Hamilton, as his own. Stephens attended Franklin College of Arts and Sciences (now the University of Georgia). He graduated at the top of his class in 1832.

Becoming a Lawyer and Politician

After teaching for a few years, Stephens studied law. He became a lawyer in Georgia in 1834. He had a very successful career in Crawfordville. He was known for defending people who were wrongly accused. None of his clients charged with serious crimes were ever executed. As he became wealthier, Stephens bought land and slaves. By the time of the Civil War, he owned 34 slaves and thousands of acres.

Stephens entered politics in 1836. He was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives and served until 1841. In 1842, he was elected to the Georgia Senate.

Serving in the U.S. Congress

Stephens served in the U.S. House from October 2, 1843, to March 3, 1859. He was first elected as a Whig. He was re-elected several times, sometimes as a Whig, sometimes as a Unionist, and later as a Democrat. As a lawmaker before the Civil War, Stephens was involved in many important debates about the country's divisions. He started as a moderate defender of slavery but later accepted the Southern arguments for it.

Stephens quickly became a leading Southern Whig in the House. He supported adding Texas to the U.S. in 1845. He was strongly against the Mexican–American War. He also opposed the Wilmot Proviso, which would have stopped slavery from spreading into new territories gained from the war.

Stephens and his friend Robert Toombs supported Zachary Taylor for president in 1848. They were upset when Taylor did not fully support their views on the Compromise of 1850. Stephens even called for Taylor to be removed from office. Stephens and Toombs supported the Compromise, which aimed to balance slave and free states. They also helped create the Georgia Platform, which brought together people in the South who wanted to stay in the Union.

Stephens and Toombs were close friends and political allies. Stephens was described as a serious and ambitious young man, while Toombs was wealthy and outgoing. Their friendship lasted throughout their lives.

Stephens left the Whig party because its Northern members often disagreed with Southern interests. In Georgia, Stephens, Toombs, and Howell Cobb formed the Constitutional Union Party. This new party won big in Georgia. Stephens spent a few years as a Constitutional Unionist, acting mostly as an independent.

In 1854, the issue of slavery in new territories came up again. Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed organizing the Nebraska Territory with the Kansas–Nebraska Act. This act allowed settlers to decide on slavery, which angered many in the North. Stephens helped pass this bill in the House, calling it "the greatest glory of my life."

After this, Stephens mostly voted with the Democrats. He strongly opposed the Know-Nothing Party because of their secrecy and their anti-immigrant views. Stephens quickly became important in the Democratic Party. He helped President James Buchanan try to make Kansas a slave state.

Stephens did not run for re-election in 1858. As the country became more divided, Stephens criticized Southern extremists. He remained friends with Stephen A. Douglas, even though many Southerners disliked Douglas. Stephens supported Douglas for president in the 1860 election.

Before the Civil War began, Stephens advised delaying military action against U.S. forts. He wanted the Confederacy to build up its forces and supplies first.

Vice President of the Confederacy

In 1861, Stephens was a delegate to the Georgia Secession Convention. This meeting was to decide Georgia's response to Abraham Lincoln's election. Stephens, known as the sage of Liberty Hall, urged the South to stay loyal to the Union. He argued that Republicans were a minority in Congress and would have to compromise. He voted against secession but said Georgia had the right to leave if Northern states ignored the Fugitive Slave Law.

He was elected to the Confederate Congress and chosen as Vice President of the provisional government. He took office on February 11, 1861, and served until his arrest on May 11, 1865.

In 1862, Stephens began to openly disagree with President Davis. Throughout the war, he spoke out against many of Davis's policies. These included the military draft, suspending the right to a fair trial, and certain financial policies.

In 1863, Davis sent Stephens on a mission to Washington, D.C., to discuss prisoner exchanges. However, after the Union victory at Gettysburg, Lincoln's government refused to meet with him. As the Confederacy's situation worsened, Stephens became more vocal in his opposition to Davis. In March 1864, Stephens gave a speech to the Georgia Legislature. In it, he strongly criticized the Davis Administration and pushed for peace. His relationship with Davis became very strained.

On February 3, 1865, Stephens was one of three Confederate officials who met with Lincoln. They met on a steamboat called the River Queen at the Hampton Roads Conference. This meeting was an attempt to end the war, but it failed. Stephens and Lincoln had been good friends and political allies in the 1840s. Although they didn't reach a peace agreement, Lincoln did agree to find Stephens's nephew, a Confederate soldier, and ordered his release.

Stephens was arrested for his role in the war at his home on May 11, 1865. He was held in Fort Warren in Boston Harbor for five months.

Cornerstone Speech

Stephens's Cornerstone Speech on March 21, 1861, is often mentioned when studying Confederate ideas. He stated that disagreements over the enslavement of African Americans were the "immediate cause" of states leaving the Union. He said the Confederate constitution had solved these issues.

Stephens argued that scientific progress showed that the United States Declaration of Independence's idea that "all men are created equal" was wrong. He criticized the founders of the U.S. Constitution. He said that unlike the United States, the Confederacy was founded on the idea that black people were not equal to white people.

After the Confederacy lost the war, he tried to say he didn't mean what he said in the speech. He claimed the war was about differences in how the Constitution was understood, not slavery. However, most historians disagree with his later explanation.

Later Life

In 1866, Stephens was elected to the United States Senate by the Georgia legislature. But he was not allowed to take his seat because of rules against former Confederates. He wrote a U.S. history book in 1868–1870. In it, he argued that states had the right to leave the Union and that the North was the aggressor. However, the Supreme Court disagreed with his legal argument in 1869.

In 1873, Stephens was elected to the United States House of Representatives again. He served there until November 4, 1882. On that day, he resigned from Congress to become Governor of Georgia. Stephens's time as governor was short. He died on March 4, 1883, just four months after taking office.

Stephens was often sick throughout his life, especially from severe rheumatoid arthritis and a back injury. He was about 5 feet 7 inches tall but often weighed less than 100 pounds. Many of his former slaves continued to work for him, sometimes for little or no pay. This was likely due to limited opportunities for former slaves in the South. These servants were with him when he died.

Personal Life

Alexander Stephens never married and had no known children.

Legacy

- Stephens is shown on the Confederate States $20.00 banknote.

- Stephens County, Georgia, and Stephens County, Texas, are named after him.

- A. H. Stephens State Park, near Crawfordville, includes his home, Liberty Hall.

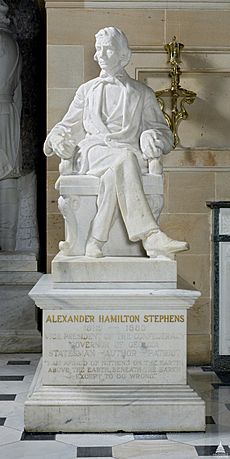

- A statue of Stephens is in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol. It represents one of two figures from Georgia history. There have been calls to replace his statue with one of someone else, like Martin Luther King Jr..

- Stephens was sometimes called "The Little Pale Star from Georgia."

See Also

In Spanish: Alexander H. Stephens para niños

In Spanish: Alexander H. Stephens para niños