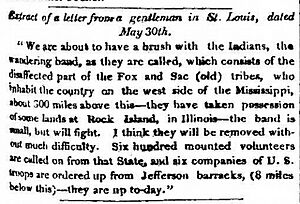

Black Hawk War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Black Hawk War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

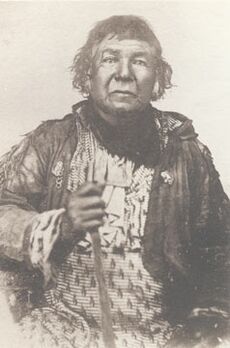

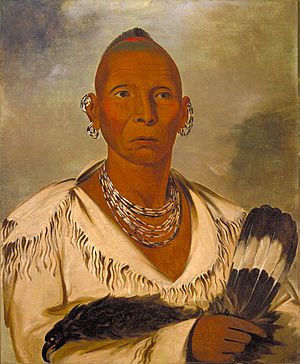

Black Hawk, the Sauk war chief and namesake of the Black Hawk War in 1832 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Ho-Chunk Menominee Dakota and Potawatomi allies |

Black Hawk's British Band with Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi allies | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

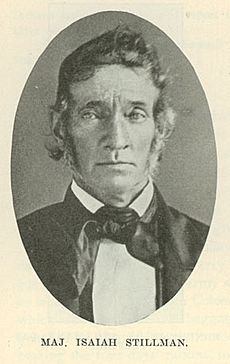

| Henry Atkinson Edmund P. Gaines Henry Dodge Isaiah Stillman Jefferson Davis Winfield Scott Robert C. Buchanan |

Black Hawk Neapope Wabokieshiek |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,000+ militiamen 630 Army regulars 700+ Native Americans |

500 warriors 600 non-combatants |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 77 killed (including non-combatants) | 450–600 killed (including non-combatants) | ||||||

The Black Hawk War was a conflict in 1832 between the United States and a group of Native Americans. This group was led by Black Hawk, a respected leader of the Sauk tribe. The war began when Black Hawk and his followers, known as the "British Band", crossed the Mississippi River into Illinois. They hoped to reclaim lands they believed were unfairly taken by the U.S. in a disputed treaty from 1804.

U.S. officials saw Black Hawk's return as a threat. They sent a local militia to confront them. On May 14, 1832, fighting broke out, and Black Hawk's warriors won an early victory at the Battle of Stillman's Run. Black Hawk then moved his people to a safer area in what is now southern Wisconsin. U.S. forces pursued them. During this time, some other Native American groups joined in raids, while many tried to stay out of the conflict. Some tribes, like the Menominee and Dakota, even supported the United States against Black Hawk's group.

U.S. forces, led by General Henry Atkinson, eventually found Black Hawk's band. On July 21, they fought at the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. Black Hawk's group, weakened by hunger and losses, retreated towards the Mississippi River. On August 2, U.S. soldiers attacked the remaining members of the British Band at the Battle of Bad Axe. Many Native Americans were killed or captured. Black Hawk and other leaders surrendered later and were held for about a year.

Many famous Americans, including future President Abraham Lincoln, participated in this war. The Black Hawk War also influenced the U.S. policy of Indian removal. This policy encouraged Native American tribes to sell their lands and move west of the Mississippi River.

Contents

Understanding the Conflict's Roots

In the 1700s, the Sauk and Meskwaki (also called Fox) tribes lived near the Mississippi River in what are now parts of Illinois and Iowa. They cherished this land for its rich soil, good hunting, and access to water for trade. These two tribes became close after moving from the Great Lakes due to earlier conflicts. By 1832, about 6,000 people lived in these combined tribes.

The Disputed Land Treaty

As the United States expanded westward, government officials wanted to buy Native American lands. In 1804, Governor William Henry Harrison made a treaty in St. Louis. A group of Sauk and Meskwaki leaders supposedly sold their lands east of the Mississippi River. They received goods and yearly payments in return.

However, this treaty became very controversial. Many Native leaders said they were not authorized to sell such large amounts of land. Historians believe the chiefs might not have understood they were giving up ownership forever. They also think the Native Americans wouldn't have sold so much valuable land for such a small price. It seems the Americans included more territory in the written treaty than the Native leaders realized. The Sauks and Meskwakis only learned the full extent of the land sale years later.

The 1804 treaty allowed the tribes to keep using the land until it was sold to American settlers. For over 20 years, the Sauks lived in Saukenuk, their main village. It was located where the Mississippi and Rock Rivers meet. In 1828, the U.S. government began surveying this land for new settlers. An Indian agent named Thomas Forsyth told the Sauks they needed to leave Saukenuk and their other homes.

Sauk Tribe Divides Over Land

The Sauk people had different ideas about what to do regarding the 1804 treaty. Most Sauks decided to move west of the Mississippi River to avoid conflict. Their leader was Keokuk. He was a skilled speaker and often represented the Sauk chiefs. Keokuk believed the 1804 treaty was unfair. However, after seeing the large American cities, he felt the Sauks could not win a war against the United States.

American officials knew Keokuk wanted peace. They gave him many gifts, hoping he would convince his people to move to Iowa. This plan worked, and Keokuk and most of the tribe decided to leave. But about 800 Sauks, roughly one-sixth of the tribe, chose to resist. Black Hawk, a respected war captain in his 60s, became their leader in 1829. He had fought against the U.S. in the War of 1812.

Black Hawk had signed a treaty in 1816 that confirmed the 1804 land sale. But he claimed the written words were different from what was discussed. He believed "whites were in the habit of saying one thing to the Indians and putting another thing down on paper." Black Hawk was determined to keep Saukenuk, his birthplace and home village.

When the Sauks returned to Saukenuk in 1829 after their winter hunt, they found settlers had moved in. After months of disagreements, the Sauks left for their next winter hunt. Keokuk hoped to avoid more trouble and told officials his followers would not return to Saukenuk.

Against Keokuk's advice, Black Hawk's group returned to Saukenuk in the spring of 1830. They were joined by over 200 Kickapoos, who were often allies. Black Hawk's followers became known as the "British Band". They sometimes flew a British flag to show they did not accept U.S. control. They also hoped for support from the British in Canada.

In 1831, the British Band returned to Saukenuk again. Black Hawk's group had grown to about 1,500 people, including some Potawatomis. American officials decided to force them out of Illinois. General Edmund P. Gaines gathered troops to try and intimidate Black Hawk. Illinois Governor John Reynolds called for about 1,500 militia volunteers. Meanwhile, Keokuk convinced many of Black Hawk's followers to leave Illinois.

On June 25, 1831, U.S. troops approached Saukenuk. Black Hawk and his followers abandoned the village and crossed back over the Mississippi. On June 30, Black Hawk and other Sauk leaders met with General Gaines. They signed an agreement promising to stay west of the Mississippi and not contact the British in Canada.

Black Hawk's Return to Illinois

In late 1831, a Sauk chief named Neapope returned from Canada. He told Black Hawk that the British and other tribes in Illinois would support the Sauks against the United States. It's unclear why Neapope said this, as his claims turned out to be false. Historians believe he might have been overly hopeful. Black Hawk was glad to hear this news, though he later blamed Neapope for misleading him. Black Hawk spent the winter trying to get more allies from other tribes, but he wasn't successful.

Neapope also reported that Wabokieshiek ("White Cloud"), a spiritual leader known as the "Winnebago Prophet," said other tribes were ready to help. Wabokieshiek's village, Prophetstown, was about 35 miles from Saukenuk. It was home to about 200 people from different tribes who were unhappy with American expansion. While some Americans later blamed Wabokieshiek for starting the war, he actually encouraged his followers to avoid fighting.

On April 5, 1832, the British Band, with about 500 warriors and 600 non-combatants (women, children, and elderly), crossed into Illinois again. They moved north from the Iowa River. Black Hawk's exact plans for re-entering Illinois are not fully clear. Some thought they wanted to reoccupy Saukenuk, while others believed they were heading to Prophetstown. Historians suggest Black Hawk himself might not have been certain of their destination.

As the British Band moved, American officials asked Wabokieshiek to tell Black Hawk to turn back. Wabokieshiek had previously encouraged Black Hawk to come to Prophetstown. He argued that the 1831 agreement only stopped them from returning to Saukenuk, not from moving to Prophetstown. Now, Wabokieshiek told Black Hawk that if his band remained peaceful, the Americans would have to let them settle. He also mentioned the hoped-for support from the British and other tribes. Black Hawk likely hoped to avoid war. The presence of women, children, and the elderly showed they were not just a war party.

Intertribal Relations and U.S. Policy

U.S. officials were worried about Black Hawk's return. They were also concerned about possible wars between different Native American tribes in the region. Many stories about the Black Hawk War focus on the conflict between Black Hawk and the U.S. But some historians point out that it also involved long-standing disagreements between Native American tribes. Tribes along the Upper Mississippi had fought for years over hunting grounds. The Black Hawk War gave some Native Americans a chance to continue these older conflicts.

After the War of 1812, the United States became the main power in the region. It tried to act as a mediator in tribal disputes. Before the Black Hawk War, the U.S. discouraged intertribal warfare. This was partly to help acquire Native American land and move tribes westward. This policy was known as Indian removal, and it became a major goal by the late 1820s. The U.S. held treaty councils to draw tribal boundaries. However, some Native Americans, especially young warriors, disliked this mediation. Warfare was an important way for them to gain respect and status.

The situation was made more complex by changes in American government jobs. After Andrew Jackson became U.S. president in 1829, many experienced Indian agents were replaced. Less qualified people, loyal to Jackson, took their places. Some historians believe the Black Hawk War might have been avoided if experienced agents like Thomas Forsyth had remained.

In 1830, violence threatened to undo American efforts for peace. Dakotas (Santee Sioux) and Menominees killed 15 Meskwakis at a treaty meeting. In response, Meskwakis and Sauks killed 26 Menominees. American officials tried to stop the Menominees from seeking revenge. But western Menominee groups formed an alliance with the Dakotas to fight the Sauks and Meskwakis.

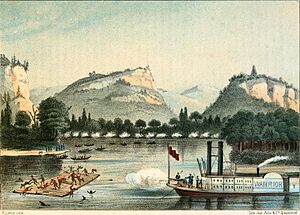

To prevent a larger war, American officials ordered the U.S. Army to arrest the Meskwakis involved in the killings. General Henry Atkinson was given this task. Atkinson was an experienced officer in administration and diplomacy, but he had never been in combat. On April 8, he traveled up the Mississippi River by steamboat with about 220 soldiers. By chance, his boats passed Black Hawk's band, who had just crossed into Illinois.

When Atkinson arrived at Fort Armstrong on April 12, he learned Black Hawk's band was in Illinois. He also found that most of the Meskwakis he wanted to arrest were with Black Hawk. Atkinson, like other American officials, believed the British Band intended to start a war. With few troops, he asked for help from the Illinois state militia. He wrote to Governor Reynolds on April 13, possibly exaggerating the threat. Governor Reynolds, who wanted to drive Native Americans out of the state, called for militia volunteers. About 2,100 men volunteered and formed a brigade. Among them was 23-year-old Abraham Lincoln, who was elected captain of his company.

Early Attempts at Peace

After General Atkinson arrived at Rock Island on April 12, 1832, he, Keokuk, and Meskwaki chief Wapello sent messages to the British Band. Black Hawk rejected these messages asking him to turn back. Colonel Zachary Taylor, an army officer under Atkinson, later said Atkinson should have tried to stop the British Band by force. Some historians agree, believing Atkinson could have prevented the war with stronger action. Others argue Atkinson was right to wait for more troops. At this point, leaders on both sides had little chance of avoiding conflict, as some militiamen and Black Hawk's warriors were eager to fight.

Meanwhile, Black Hawk learned that the Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi tribes were less supportive than he expected. Different groups within these tribes often had different goals. Ho-Chunks living along the Rock River, who had family ties to the Sauks, cautiously supported the British Band. They tried not to anger the Americans. Ho-Chunks in Wisconsin were more divided. Some remembered their loss to the Americans in the 1827 Winnebago War and stayed out of the conflict. Other Ho-Chunks, allied with the Dakotas and Menominees, wanted to fight against the British Band.

Most Potawatomis wanted to remain neutral. However, many settlers distrusted them, remembering the Fort Dearborn massacre of 1812. Potawatomi leaders worried their tribe would be punished if any members helped Black Hawk. At a meeting near Chicago on May 1, 1832, Potawatomi leaders declared that any Potawatomi supporting Black Hawk would be considered a traitor. In mid-May, chiefs Shabonna and Waubonsie told Black Hawk that neither they nor the British would help him.

Without British supplies, enough food, or Native allies, Black Hawk realized his band was in serious trouble. Some reports say he was ready to negotiate with Atkinson to end the crisis. But an unfortunate encounter with Illinois militiamen ended any chance for a peaceful solution.

The Battle of Stillman's Run

General Samuel Whiteside's militia brigade joined federal service under General Atkinson in late April. Atkinson allowed Governor Reynolds, Whiteside, and the militiamen to go up the Rock River. He told them to "move upon the Indians should they be within striking distance without waiting for my arrival." Governor Reynolds joined the expedition.

On May 10, the militia reached Prophetstown while pursuing the British Band. They burned the empty village and continued to Dixon's Ferry, waiting for Atkinson. On May 12, eager militiamen led by Major Isaiah Stillman left Whiteside's camp. They made another camp about 25 miles away. Seeing a small group of Native Americans with a red flag, some men pursued them. They killed one Native American before returning to camp.

Near dusk on May 14, Black Hawk and his warriors attacked Stillman's party. This became known as the Battle of Stillman's Run. Black Hawk later said he sent three men with a white flag to talk, but the Americans captured them. He claimed they then fired on a second group of messengers. Some militiamen said they never saw a white flag. All accounts agree that Black Hawk's warriors attacked the camp at dusk. The much larger militia force was defeated, and survivors fled back to Whiteside's camp. Black Hawk's 40 warriors killed 12 Illinois militiamen, suffering only three losses.

The Battle of Stillman's Run was a turning point. Before this, Black Hawk had not fully committed to war. Now, he wanted revenge. American leaders, including President Jackson, refused to consider peace after this defeat. They wanted a clear victory over Black Hawk to discourage other Native American uprisings.

Early Raids and Attacks

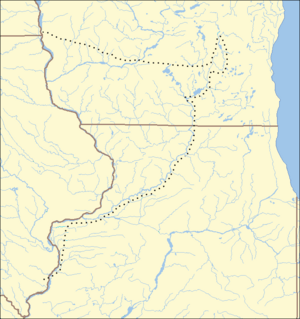

| Map of Black Hawk War sites Symbols are wikilinked to article |

With fighting now underway, Black Hawk sought a safe place for the women, children, and elderly in his band. They accepted an offer from the Rock River Ho-Chunks and camped in an isolated spot at Lake Koshkonong in the Michigan Territory. With the non-combatants secure, members of the British Band, along with some Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi allies, began raiding settlers. Not all Native Americans supported these actions. Potawatomi chief Shabonna rode through settlements, warning people of upcoming attacks.

The first attacks were mainly by Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi warriors. On May 19, 1832, Ho-Chunks ambushed six men near Buffalo Grove, killing one man. Days later, Indian agent Felix St. Vrain and three other men were killed near Kellogg's Grove.

Some Ho-Chunks and Potawatomis who joined the war had their own reasons for fighting. One example was the Indian Creek massacre. Potawatomis living along Indian Creek were upset because a settler had built a dam, stopping fish from reaching their village. The settler ignored their complaints and attacked a Potawatomi man. The Black Hawk War gave these Potawatomis a chance for revenge. On May 21, about 50 Potawatomis and three Sauks attacked the settlement. They killed 15 people and kidnapped two teenagers. A Ho-Chunk chief later helped negotiate their release. This chief, like others, tried to calm the Americans while secretly helping the British Band.

American Forces Reorganize

News of Stillman's defeat and the attacks caused panic among settlers. Many fled to Chicago, which was then a small town. It became crowded with refugees. Many Potawatomis also fled to Chicago, wanting to avoid the conflict and not be mistaken for enemies. Throughout the region, settlers quickly formed militia units and built small forts.

After Stillman's defeat on May 14, the regular army and militia continued up the Rock River to find Black Hawk. The militiamen became discouraged when they couldn't find the British Band. When they heard about the raids, many left to defend their families. Morale dropped, and Governor Reynolds asked his officers if they should continue the campaign. General Whiteside, unhappy with his men, voted to disband the force. Most of Whiteside's brigade disbanded on May 28. About 300 men, including Abraham Lincoln, agreed to stay for 20 more days until a new militia could be organized.

In June 1832, General Atkinson formed a new force called the "Army of the Frontier." It included 629 regular army soldiers and 3,196 mounted militia volunteers. The militia was divided into three brigades. Many men were assigned to local patrols, so Atkinson had about 450 regulars and 2,100 militiamen for campaigning. Many more militiamen served in other units. Abraham Lincoln, for example, re-enlisted as a private. Henry Dodge, a Michigan militia colonel, led a battalion of 250 mounted volunteers and became one of the best commanders in the war. The total number of militiamen who fought is not fully known, but estimates for Illinois alone are between six and seven thousand.

Atkinson also began recruiting Native American allies, changing the previous U.S. policy of preventing intertribal warfare. Menominees, Dakotas, and some Ho-Chunk bands were eager to fight the British Band. By June 6, about 225 Native Americans had gathered. This force included about 80 Dakotas, 40 Menominees, and several Ho-Chunk bands. Atkinson placed them under the command of William S. Hamilton, a militia colonel. However, Hamilton proved to be a poor leader. The Native warriors became frustrated and many eventually left to fight on their own terms.

June Raids and Battles

In June 1832, after hearing Atkinson was forming a new army, Black Hawk began sending out raiding parties. He might have hoped to draw the Americans away from his camp at Lake Koshkonong. The first major attack happened on June 14 near South Wayne, Wisconsin. A group of about 30 warriors attacked farmers, killing four.

In response, militia Colonel Henry Dodge gathered 29 mounted volunteers. On June 16, Dodge and his men cornered about 11 raiders at a bend in the Pecatonica River. In a short battle, the Americans killed all the Native Americans. The Battle of Horseshoe Bend (or Battle of Pecatonica) was the first real American victory. It helped restore public confidence in the militia.

On the same day, another skirmish took place at Kellogg's Grove in Stephenson County, Illinois. American forces were there to stop raiding parties. In the First Battle of Kellogg's Grove, militia led by Adam W. Snyder pursued about 30 British Band warriors. Three Illinois militiamen and six Native warriors died. Two days later, on June 18, militia under James W. Stephenson fought what was likely the same group near Yellow Creek. The Battle of Waddams Grove was a tough, hand-to-hand fight. Three militiamen and five or six Native Americans were killed.

On June 6, a miner was killed near Blue Mounds in the Michigan Territory. Residents feared the Rock River Ho-Chunks were joining the war. On June 20, a Ho-Chunk raiding party, estimated at 100 warriors, attacked the settler fort at Blue Mounds. Two militiamen were killed, one of whom was badly injured.

On June 24, 1832, Black Hawk and about 200 warriors attacked the Apple River Fort, near Elizabeth, Illinois. Settlers had taken refuge in the fort, defended by 20 to 35 militiamen. The Battle of Apple River Fort lasted about 45 minutes. Women and girls inside the fort helped by loading muskets and making bullets. After losing several men, Black Hawk ended the siege, looted nearby homes, and returned to his camp.

The next day, June 25, Black Hawk's party met a militia battalion. In the Second Battle of Kellogg's Grove, Black Hawk's warriors pushed the militiamen into their fort and began a two-hour siege. After losing nine warriors and killing five militiamen, Black Hawk ended the siege and returned to his main camp. This was Black Hawk's last military success. With his band running low on food, he decided to lead them back across the Mississippi.

The Final Campaign

On June 15, 1832, President Andrew Jackson appointed General Winfield Scott to take command. Scott gathered about 950 troops from eastern army posts. However, a cholera pandemic had spread, and many of Scott's men became sick and died as they traveled. By the time Scott reached Chicago, he had only about 350 healthy soldiers left. On July 29, Scott hurried west, hoping to take command of the war's final campaign, but he arrived too late for any fighting.

General Atkinson, learning Scott would take over, hoped to end the war before Scott arrived. The Americans had trouble finding the British Band, partly due to misleading information from some Native Americans. Potawatomis and Ho-Chunks in Illinois, many of whom wanted to stay neutral, decided to cooperate with the Americans. Tribal leaders knew some of their warriors had helped the British Band. They hoped a clear show of support for the Americans would prevent punishment after the war. Wearing white headbands to show they were allies, Ho-Chunks and Potawatomis guided Atkinson's army. However, some Ho-Chunks sympathetic to Black Hawk's people misled Atkinson. They made him think the British Band was still at Lake Koshkonong. While Atkinson's men struggled through swamps, the British Band had moved miles north.

In mid-July, Colonel Dodge learned from a trader that the British Band was camped near the Rock River rapids. Dodge and James D. Henry set out in pursuit on July 15. The British Band, reduced to fewer than 600 people due to deaths and desertions, headed for the Mississippi River as the militia approached. The Americans pursued them, killing several Native Americans who lagged behind.

Battle of Wisconsin Heights

On July 21, 1832, the militiamen caught up with the British Band near Sauk City, Wisconsin. To give the non-combatants time to cross the Wisconsin River, Black Hawk and Neapope fought the Americans in a rear-guard action. This became known as the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. Black Hawk was greatly outnumbered, leading about 50 Sauks and 60 to 70 Kickapoos against 750 militiamen. The battle was a clear victory for the militiamen, who lost only one man while killing as many as 68 of Black Hawk's warriors. Despite the losses, the battle allowed most of the British Band, including many women and children, to escape across the river. Black Hawk's ability to hold off a larger force impressed some U.S. Army officers.

The Battle of Wisconsin Heights was a victory for the militia; no regular U.S. Army soldiers were present. Atkinson and the regulars joined the volunteers several days later. With about 400 regulars and 900 militiamen, the Americans crossed the Wisconsin River on July 27. They continued pursuing the British Band. Black Hawk's group moved slowly, burdened by wounded warriors and people dying of starvation.

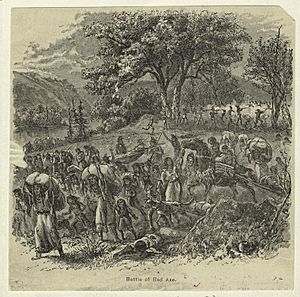

The Battle of Bad Axe

After the Battle of Wisconsin Heights, a messenger from Black Hawk shouted to the militiamen that the starving British Band was going back across the Mississippi and would fight no more. However, no one in the American camp understood the message because their Ho-Chunk guides were not there to interpret. Black Hawk may have believed the Americans understood and would let his band cross the Mississippi peacefully.

The Americans, however, had no intention of letting the British Band escape. The Warrior, a steamboat with an artillery piece, patrolled the Mississippi River. American-allied Dakotas, Menominees, and Ho-Chunks watched the riverbanks. On August 1, the Warrior arrived at the mouth of the Bad Axe River. The Dakotas told the Americans they would find Black Hawk's people there. Black Hawk raised a white flag to surrender, but his intentions might have been misunderstood. The Americans, not wanting to accept a surrender, thought it was a trick for an ambush. When they confirmed the Native Americans on land were the British Band, they opened fire. Twenty-three Native Americans were killed, while only one soldier on the Warrior was injured.

After the Warrior left, Black Hawk decided to seek safety with the Ojibwes to the north. Only about 50 people, including Wabokieshiek, went with him. The others stayed, determined to cross the Mississippi and return to Sauk territory. The next morning, August 2, Black Hawk was heading north when he learned the American army had surrounded the British Band trying to cross the Mississippi. He tried to rejoin them, but after a skirmish with American troops, he gave up. Sauk chief Weesheet later criticized Black Hawk and Wabokieshiek for leaving their people during the final battle.

The Battle of Bad Axe began around 9:00 am on August 2. The Americans caught up with the remaining British Band members a few miles downstream from the Bad Axe River. The British Band had about 500 people, including 150 warriors. The warriors fought the Americans while the Native non-combatants desperately tried to cross the river. Many reached nearby islands, but the steamboat Warrior returned at noon, carrying regulars and Menominees. They forced the Native Americans off the islands.

The battle was another one-sided victory for the Americans, who lost only 14 men. At least 260 members of the British Band were killed, including about 110 who drowned trying to cross the river.

Menominees from Green Bay, who had mobilized nearly 300 men, arrived too late for the battle. They were disappointed to have missed fighting their old enemies. On August 10, General Scott sent 100 of them after a group of the British Band that had escaped. The Menominees tracked down about ten Sauks, killing two warriors.

The Dakotas, who had volunteered 150 warriors, also arrived too late for the Battle of Bad Axe. But they pursued British Band members who crossed the Mississippi into Iowa. Around August 9, in the final engagement of the war, they attacked the remaining British Band along the Cedar River. They killed 68 and took 22 prisoners.

Aftermath and Legacy

The Black Hawk War resulted in the deaths of 77 settlers, militiamen, and regular soldiers. This number does not include the many deaths from cholera among General Winfield Scott's relief force. Estimates for the British Band's losses range from 450 to 600 people. This means about half of the 1,100 people who entered Illinois with Black Hawk in 1832 died during the conflict.

Many American men who later became famous participated in the Black Hawk War. At least seven future U.S. Senators fought, as did four future Illinois governors. Future governors of Michigan, Nebraska, and the Wisconsin Territory also took part. Two future U.S. presidents, Taylor and Lincoln, were involved. The war showed American officials the need for mounted troops to fight against enemies on horseback. After the war, Congress created the Mounted Ranger Battalion, which later became the 1st Cavalry Regiment in 1833.

Black Hawk's Imprisonment and Symbolism

After the Battle of Bad Axe, Black Hawk, Wabokieshiek, and their followers traveled northeast to seek safety with the Ojibwes. American officials offered a reward for Black Hawk's capture. While camping near Tomah, Wisconsin, Black Hawk's group was seen by a Ho-Chunk man. He alerted his village chief, who convinced Black Hawk to surrender to the Americans. On August 27, 1832, Black Hawk and Wabokieshiek surrendered at Prairie du Chien. Colonel Zachary Taylor took custody of the prisoners. They were sent by steamboat to Jefferson Barracks, escorted by Lieutenants Jefferson Davis and Robert Anderson.

By the end of the war, Black Hawk and 19 other leaders were held at Jefferson Barracks. Most prisoners were released in the following months. But in April 1833, Black Hawk, Wabokieshiek, Neapope, and three others were moved to Fort Monroe in Virginia. The American public was eager to see the captured Native Americans. Large crowds gathered in Louisville and Cincinnati to watch them pass. On April 26, the prisoners briefly met President Jackson in Washington, D.C., before going to Fort Monroe. Even in prison, they were treated like celebrities. They posed for portraits by artists and attended a dinner in their honor.

American officials decided to release the prisoners after a few weeks. First, however, the Native Americans had to visit several large U.S. cities on the East Coast. This was a common tactic to show Native American leaders the size and power of the United States. It was hoped this would discourage future resistance. Starting on June 4, 1833, Black Hawk and his companions toured Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. They attended dinners and plays, saw a battleship, public buildings, and a military parade. Huge crowds gathered to see them. Black Hawk's handsome son, Nasheweskaska (Whirling Thunder), was especially popular. However, reactions in the west were less welcoming.

Historians note that Black Hawk became a symbol of resistance for Native Americans. He also became a figure admired by some Americans in the East. Many memorials were later built in his honor. This helped shape how people remembered the Black Hawk War.

Treaties and Native American Relocation

The Black Hawk War marked the end of armed Native American resistance to U.S. expansion in the Old Northwest. The war gave American officials like Andrew Jackson and Lewis Cass a reason to push Native American tribes to sell their lands east of the Mississippi River. This was part of the Indian removal policy. After the war, many treaties were made to buy the remaining Native American land claims in the Old Northwest. The Dakotas and Menominees, who helped the Americans, largely avoided immediate pressure to move.

After the war, American officials learned that some Ho-Chunks had helped Black Hawk more than previously known. Eight Ho-Chunks were briefly imprisoned, but charges were dropped due to lack of witnesses. In September 1832, General Scott and Governor Reynolds made a treaty with the Ho-Chunks. The Ho-Chunks gave up all their land south of the Wisconsin River. In return, they received a strip of land in Iowa and yearly payments. This land in Iowa was called the "Neutral Ground." It was meant to be a buffer zone between the Dakotas and their enemies, the Sauks and Meskwakis. Scott hoped this would help keep the peace. Ho-Chunks remaining in Wisconsin were later pressured to sign another removal treaty in 1837. General Atkinson was assigned to use the army to forcibly relocate those Ho-Chunks who refused to move to Iowa.

Following the Ho-Chunk treaty, Scott and Reynolds made another treaty with the Sauks and Meskwakis. Keokuk and Wapello were the main representatives. Scott told the chiefs that if one part of a nation went to war, the whole nation was responsible. The tribes sold about 6 million acres of land in eastern Iowa to the United States. They received yearly payments and other provisions. Keokuk was given a reservation within the ceded land and recognized as the main chief. The tribes sold this reservation in 1836 and more land in Iowa the next year. Their last lands in Iowa were sold in 1842, and most Native Americans moved to a reservation in Kansas.

Because Potawatomi leaders helped the U.S. during the war, American officials did not take their tribal land as punishment. Only three individuals accused of leading the Indian Creek massacre were tried, but they were found not guilty. Nevertheless, efforts to buy Potawatomi land west of the Mississippi began in October 1832. Commissioners bought a large amount of Potawatomi land, even though not all bands were represented. The tribe was forced to sell their remaining land in a treaty held in Chicago in September 1833.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de Halcón Negro para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de Halcón Negro para niños

- Second Black Hawk War

- Sixty Years' War

- Indigenous response to colonialism