Battle of Bad Axe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bad Axe Massacre |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Black Hawk War | |||||||

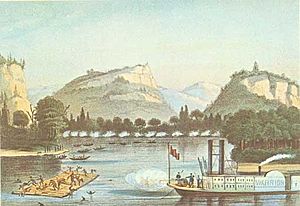

The American steamboat, Warrior at the Battle of Bad Axe attacking fleeing Sauk and Fox Indians trying to escape across the Mississippi River which resulted in a massacre in the last major engagement of the Black Hawk War |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Sauk and Fox affiliated with the British Band | Dakota Sioux | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Black Hawk (Not present on second day) |

Henry Atkinson

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| appx. 500 (including non-combatants) | appx. 1,300 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| at least 150 KIA (including non-combatants) 75 captured |

5 KIA, 19 WIA | ||||||

The Bad Axe Massacre was a terrible event where many Sauk and Fox Native Americans were killed. It happened on August 1–2, 1832, by the United States Army and local soldiers. This event was the final major battle of the Black Hawk War. It took place near a town now called Victory, in Wisconsin.

This sad event ended the war between white settlers and the Sauk and Fox tribes. These tribes were led by a warrior named Black Hawk. The massacre happened after Black Hawk's group was trying to escape. They were being chased by soldiers after the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. The soldiers caught up to them near the Mississippi River. Many historians have called this event a massacre since the 1850s. The fighting lasted two days. A steamboat called the Warrior was involved on both days. By the second day, Black Hawk and most of the Native American leaders had left. But many of their people remained behind. This victory for the United States was very harsh. It opened up a lot of land in Illinois and Wisconsin for new settlers.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

In 1804, a treaty was signed between the governor of Indiana Territory and some leaders of the Sauk and Fox tribes. This treaty gave about 50 million acres of their land to the United States. In return, the tribes received $2,234.50 and $1,000 each year. The treaty also said the Sauk and Fox could stay on their land until it was sold.

However, this treaty was not agreed upon by everyone. Black Hawk, a Sauk war leader, and others said the full tribal councils were not asked. They believed the leaders who signed the treaty did not have the right to give away the land. In the 1820s, lead was found near Galena, Illinois. Miners started moving onto the land that was part of the 1804 treaty. When the Sauk and Fox returned from their winter hunt in 1829, they found their homes taken. They were forced to move west of the Mississippi River.

Black Hawk was very upset about losing his homeland. Between 1830 and 1831, he led his people back into Illinois several times. Each time, he was convinced to return west without fighting. In April 1832, Black Hawk hoped other tribes and the British would help him. He led his group, called the "British Band", into Illinois again. This group included about 1,000 warriors and their families.

He found no allies, so he tried to go back across the Mississippi River to what is now Iowa. But the Illinois soldiers attacked, leading to Black Hawk's surprising win at the Battle of Stillman's Run. After this, more fights happened. Soldiers from Michigan Territory and Illinois were called to find Black Hawk's group. This conflict became known as the Black Hawk War.

Many smaller battles and attacks happened between May and June 1832. These included fights at Buffalo Grove and the Indian Creek massacre. Two important battles, Horseshoe Bend and Waddams Grove, helped change how people saw the soldiers. The Battle of Apple River Fort on June 24 was a 45-minute gunfight. It was between soldiers inside Apple River Fort and Black Hawk's warriors.

After these battles, Black Hawk and his group fled through modern-day Wisconsin. They were trying to escape the soldiers. They passed through places like Beloit and Janesville. They then followed the Rock River towards Horicon Marsh. From there, they went west towards the Four Lakes area, near modern-day Madison. On July 21, 1832, the soldiers caught up with Black Hawk's group. This happened as they tried to cross the Wisconsin River, near Roxbury, Wisconsin. This fight was called the Battle of Wisconsin Heights.

Before the Final Battle

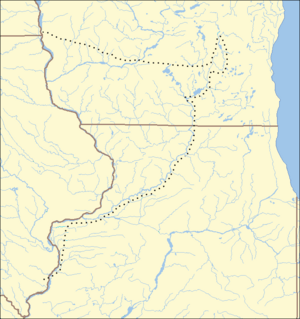

| Map of Black Hawk War sites Symbols are wikilinked to article |

A few hours after midnight on July 22, Black Hawk's group was resting. They were on a hill at the Wisconsin Heights Battlefield. Neapope, one of Black Hawk's main leaders, tried to talk to the soldiers. He wanted to explain that his group just wanted to stop fighting. They wished to go back across the Mississippi River. He spoke loudly in his native Ho-Chunk language. He thought the Ho-Chunk guides with the soldiers would understand. But the U.S. troops did not understand him. Their Sauk allies had already left the battlefield. After this failed attempt at peace, Neapope left and went to a nearby Ho-Chunk village.

The "British Band" had slowly broken apart during the conflict. Most of the Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi who had joined them were gone by the time of the Bad Axe Massacre. Many others, especially children and older people, had died from hunger. This happened as the group fled through the swamps around Lake Koshkonong.

After the fight at Wisconsin Heights, the soldiers decided to wait. They would pursue Black Hawk the next day. They heard Neapope's speech but did not understand it. To their surprise, Black Hawk's group had disappeared by morning. The battle was a military defeat for the British Band. But it allowed many of them to escape across the Wisconsin River. This safety was only temporary for many. A group of Fox women and children tried to escape down the Wisconsin River. They were captured by U.S.-allied tribes or shot by soldiers.

During the night, Black Hawk and the remaining warriors crossed the river. This was near what is now Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin. The non-combatants escaped in canoes. The group then fled west over rough land. They headed towards the Mississippi River. They had about a week's head start on the soldiers.

While Black Hawk's group fled, General Henry Atkinson made his force smaller. He took a few hundred men to join other commanders, Henry Dodge and James D. Henry. They regrouped and got new supplies at Fort Blue Mounds. Under Atkinson's command, about 1,300 men crossed the Wisconsin River. This happened between July 27–28 near Helena, Wisconsin.

The well-fed and rested soldiers found Black Hawk's trail again on July 28. This was near Spring Green, Wisconsin. They quickly caught up to the hungry and tired Native American group. On August 1, Black Hawk and about 500 people arrived at the Mississippi River. They were a few miles downstream from the Bad Axe River. When they arrived, the leaders, including Black Hawk, held a meeting. They discussed what to do next.

The Battle of Bad Axe

First Day of Fighting

On August 1, 1832, near the Bad Axe River, Black Hawk and White Cloud held a council. White Cloud was a Winnebago prophet and a leader in the British Band. They told the group not to waste time building rafts to cross the Mississippi River. They said the U.S. forces were too close. Instead, they urged everyone to flee north and find safety with the Ho-Chunk tribe. However, most of the group chose to try and cross the river.

Some people managed to escape across the Mississippi River that afternoon. But then the steamboat Warrior appeared. It was commanded by Captain Joseph Throckmorton. The steamboat stopped the group's attempt to cross to safety. Black Hawk tried to surrender by waving a white flag. But the soldiers did not understand, just like before. The situation quickly turned into a battle. The warriors who survived the first shots found cover and fired back. A two-hour gunfight followed. The Warrior eventually left the battle because it ran out of fuel. It returned to Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

Newspaper reports at the time said 23 Native Americans were killed. This included a 19-year-old woman who was shot while holding her child. Lieutenant Anderson rescued her child after the battle. The baby's arm was removed, and the child was taken to Prairie du Chien. It is believed the child recovered. This fight convinced Black Hawk that safety was to the north, not across the Mississippi. In one of his last acts as a leader, Black Hawk told his followers to flee north with him. Many did not listen. Late on August 1, Black Hawk, White Cloud, and about three dozen others left the British Band. They fled north. Most of the remaining warriors and their families stayed on the east bank of the Mississippi. The Warrior only had one person injured. A retired soldier was wounded in the knee.

Second Day of Fighting

At 2 a.m. on August 2, the soldiers woke up and started to pack their camp. They set out before sunrise. They had moved only a few miles when they met the scouts of the remaining Sauk and Fox forces. The Sauk scouts tried to lead the enemy away from the main camp. They were successful at first. The U.S. forces got into battle formation. Generals Alexander and Posey were on the right side. Henry was on the left, and Dodge and the regular soldiers were in the middle.

As the Native Americans moved back towards the river, the left side of the soldiers was left behind. When a group of soldiers found the main path to the camp, the scouts could only fight while retreating. They hoped they had given their friends a chance to escape. The Sauk and Fox kept moving back to the river. However, the Warrior steamboat returned. It had gotten more wood in Prairie du Chien. It left about midnight and arrived at Bad Axe around 10 a.m. A terrible slaughter followed, lasting for the next eight hours.

Henry's men, the entire left side, went down a hill. They found themselves among several hundred Sauk and Fox warriors. A desperate fight with bayonets and muskets began. Women and children fled the fight into the river. Many drowned right away. The battle continued for 30 minutes. Then Atkinson arrived with Dodge's middle group. This cut off escape for many of the remaining Native warriors. Some warriors managed to escape to a small island covered in willows. The Warrior fired canister shot and gunfire at this island.

The soldiers killed everyone who tried to run for cover or cross the river. Men, women, and children were all shot dead. More than 150 people were killed right there at the battle site. Many who fought there later called it a massacre. U.S. forces captured another 75 Native Americans. Out of 400–500 Sauk and Fox at Bad Axe on August 2, most were killed. Others escaped across the river. But those who escaped found only temporary safety. Many were captured and killed by Sioux warriors. These Sioux warriors were helping the U.S. Army. The Sioux brought back evidence of their success and 22 prisoners to the U.S. Indian agent Joseph M. Street in the weeks after the battle. The United States had five soldiers die and 19 injured.

Why It's Called a Massacre

On August 3, 1832, the day after the battle, Indian Agent Street wrote a letter. He described the scene at Bad Axe. He said most of the Sauk and Fox were shot in the water or drowned. They were trying to cross the Mississippi to safety. Major John Allen Wakefield wrote a book about the war in 1834. His book said that killing women and children was a mistake:

During the engagement we killed some of the squaws through mistake. It was a great misfortune to those miserable squaws and children, that they did not carry into execution [the plan] they had formed on the morning of the battle -- that was, to come and meet us, and surrender themselves prisoners of war. It was a horrid sight to witness little children, wounded and suffering the most excruciating pain, although they were of the savage enemy, and the common enemy of the country."

Black Hawk himself, even though he wasn't there on the second day, called the event a massacre. Later historical writings also criticized the actions of the white soldiers at Bad Axe. A book from 1887 by Perry A. Armstrong called the steamboat captain's actions "inhuman and dastardly." In 1898, during a ceremony for the battle's 66th anniversary, Reuben Gold Thwaites called the fight a "massacre." He repeated this idea in a collection of essays in 1903.

Today, historians still describe the battle as a complete massacre. Mark Grimsley, a history professor, said in 2005 that the Battle of Bad Axe should be called a massacre. Kerry A. Trask's 2007 book, Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America, used Wakefield's writings. Trask said that soldiers were driven by ideas of bravery and manliness. This led them to enjoy and pursue killing and wiping out the Sauk and Fox. Trask concluded that Wakefield's statement, "I must confess, that it filled my heart with gratitude and joy, to think that I had been instrumental, with many others, in delivering my country of those merciless savages, and restoring those people again to their peaceful homes and firesides," was a common view among the soldiers.

What Happened After

The Black Hawk War of 1832 led to the deaths of at least 70 settlers and soldiers. Hundreds of Black Hawk's people also died. Besides those killed in battle, a group of soldiers under General Winfield Scott also suffered. Many hundreds left the army or died from a disease called cholera. The end of the war at Bad Axe removed the big threat of Native American attacks in northwest Illinois. This allowed more settlers to move into Illinois and what became Iowa and Wisconsin.

The members of the British Band, and other tribes who joined them, suffered many deaths during the war. Some died fighting. Others were hunted down and killed by Sioux, Menominee, Ho-Chunk, and other Native tribes. Still others died from hunger or drowned. This happened during their long journey up the Rock River towards the Bad Axe River. The entire British Band was not wiped out at Bad Axe. Some survivors slowly returned to their villages. This was easier for the Potawatomi and Ho-Chunk members. Many Sauk and Fox found it harder to return home. Some returned safely, but others were held by the army.

Prisoners, some taken at the Battle of Bad Axe, were taken to Fort Armstrong in modern Rock Island, Illinois. About 120 prisoners, including men, women, and children, waited until the end of August. They were then released by General Winfield Scott.

Black Hawk and most of the British Band leaders were not captured right away. On August 20, Sauk and Fox leaders under Keokuk turned over Neapope and several other chiefs to Winfield Scott. Black Hawk, however, remained free. After escaping the battle, Black Hawk went northeast. He was with White Cloud and a small group of warriors. The group camped for a few days. They were eventually told by a group of Ho-Chunk, including White Cloud's brother, to surrender. At first, they did not want to surrender. But the group eventually traveled to the Ho-Chunk village at La Crosse. They prepared to surrender. On August 27, 1832, Black Hawk, White Cloud, and the rest of the British Band surrendered to Joseph M. Street at Prairie du Chien.

Images for kids

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |