Wapasha II facts for kids

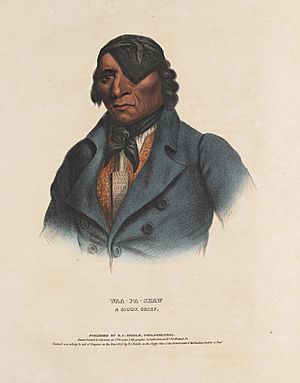

Wabasha II (born around 1773, died 1836) was an important leader of the Mdewakanton Dakota tribe. He was also known as Wapahasha or "The Leaf." He became the head chief after his father in the early 1800s.

Chief Wabasha II led his Dakota people who fought with the British during the War of 1812. Later, he sided with the United States in the Black Hawk War of 1832. He also signed important agreements called the Treaties of Prairie du Chien in 1825 and 1830.

In 1843, a town was named "Wabasha" in Minnesota to honor him. Today, you can see a statue of Chief Wabasha II in Wabasha, Minnesota, near the Mississippi River.

Contents

Life and Changes for the Dakota

In the late 1700s, the Mdewakanton Dakota lived in a very large village called Titankatanni. It was on the lower Minnesota River and had many homes. But by 1805, this big village split up. There wasn't enough game (animals for hunting) nearby for everyone.

Chief Wabasha II led a group called the Kiyuksa (Keoxa) band. In the early 1800s, his band often moved between the upper Iowa River and Lake Pepin. They hunted on both sides of the upper Mississippi River. By 1830, Wabasha's Kiyuksa band became very large, much bigger than other Mdewakanton groups.

Family Connections

Wabasha had family ties to French Canadian fur traders. One was Jean Joseph Rolette, who married Wabasha's niece. Wabasha often helped Rolette when there were problems with hunters. Rolette likely gave Wabasha advice on important matters, like the War of 1812 and dealing with the Americans.

Another fur trader connected to Wabasha was Augustin Rocque. His mother was one of Wabasha's sisters.

Early Meetings with Americans

Pike's Journey

In 1805, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike met with Chief Wabasha near the Iowa River. Pike was on his first journey to explore the area. On September 23, 1805, he talked with seven Mdewakanton chiefs. He wanted to buy a large piece of land (100,000 acres) so the United States could build a fort. Only two chiefs signed this agreement, known as the Treaty of St. Peters.

In April 1806, Pike returned to the Minnesota River. This time, over forty chiefs from different Dakota bands came to a meeting. Pike tried to get the Dakota and Ojibwe to make peace, but it was difficult. He hoped some Dakota leaders would go with him to St. Louis for more talks, but none did.

After the meeting, Pike visited Wabasha's village again on his way back to St. Louis.

Trip to St. Louis

In May 1806, a group of Dakota men, including four chiefs, traveled down the Mississippi River to St. Louis. They went to meet General James Wilkinson. However, General Wilkinson soon left St. Louis because of his involvement in a plot, and other people had to handle relations with the Dakota.

War of 1812

Chief Wabasha II led Dakota fighters who supported the British in the War of 1812. Many Native American tribes, including the Dakota, joined the British against the Americans. Pike's attempts to make them loyal to the US had not worked.

Supporting the British

Before the war started, British fur trader Robert Dickson held a meeting with many tribes. Chiefs Wabasha II and Little Crow I spoke in favor of supporting the British. Wabasha said that English traders had always helped them, while American promises were "not the songs of truth."

The Americans had not built the fort and trading post they promised in 1805. Meanwhile, Robert Dickson had given many goods to the Dakota, who had a very hard winter in 1811–12. The British also suggested creating a permanent Native American nation, closed to settlers, between Canada and the United States.

Leading in Battle

Robert Dickson and other traders became British army officers. Wabasha and Little Crow were named generals of the Native American forces. In July 1812, British forces and over 400 Native Americans quickly captured Fort Mackinac. In the winter of 1812–1813, Chief Wabasha led his Mdewakanton forces west for their winter hunt.

In February 1813, Chief Wabasha was ordered to bring his men to Prairie du Chien. That summer, 97 Dakota warriors fought in battles near Detroit. They took part in attacks on Fort Meigs and Fort Stephenson near Lake Erie in 1813, but these attacks were not successful.

Unhappiness Among Dakota Warriors

The British failing to capture the forts disappointed many Dakota warriors. They also felt they had received very little for their help. In late 1813, Colonel Robert Dickson could not deliver supplies to the west. This tested even Wabasha's patience. When his people complained about not having enough guns or ammunition, Chief Wabasha showed them the medals and flags he had received from the Americans. This showed he could still work with the Americans if needed.

In February 1814, Colonel Dickson finally brought supplies to the upper Mississippi River. Wabasha thanked him, but for many unhappy fighters, it was too late.

During the Siege of Prairie du Chien in the summer of 1814, Wabasha's men supported the British but did not join the fighting. After the Americans gave up Fort Shelby, the Mdewakanton warriors mostly protected the defeated US troops from the Ho-Chunks.

Over the winter of 1814–15, the British kept their fort at Prairie du Chien to make sure the Native Americans stayed neutral. Chief Wabasha continued to support the British openly. However, the British knew he also met with tribes who supported the Americans. Still, the British saw Wabasha as key to controlling the area and kept giving him supplies.

Meeting on Drummond Island

After the United States and the United Kingdom signed the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, Native Americans felt betrayed. They felt the British had "sold them out." Canadian fur traders were also surprised that no new land was gained; the border stayed the same.

In 1816, the British held a meeting with western Native American tribes on Drummond Island. They praised the Sioux for their bravery in the War of 1812 and offered gifts. But Wabasha II and Little Crow I refused the gifts. They gave speeches showing their anger at the British for not protecting Native American interests.

Chief Wabasha told a British officer: "We never knew of this peace. We are told it was made by our Great Father... What is that to us? Will these presents pay for the men we have lost in battle?...Will they make good your promises?”

Because of this, the British officer wrote many letters arguing that Britain should stop the United States from building military forts in Native American territory. The Native Americans had not given permission for these forts.

Mixed Feelings About Americans

While the British met on Drummond Island, American officials met with some eastern Sioux near St. Louis. Over forty Dakota leaders signed an agreement in 1816. They promised peace and agreed to all past deals with the United States, including Pike's 1805 treaty.

On their way back from Drummond Island, Wabasha and Little Crow were stopped by an American general. The general said only Dakota who had made peace with the Americans could camp north of the town. He showed off a gunboat to prove his point. Even though Wabasha's men were unhappy, Wabasha and Little Crow got permission to visit their relatives.

The next morning, Wabasha and Little Crow gave up their British flags and medals. They promised to support "their American father." They then returned to Prairie du Chien with American flags flying from their canoes and were welcomed with a celebration. The American general thought Chief Wabasha, a wise leader, had been won over.

However, a different American official, William Clark, was not so sure. He knew that Robert Dickson was building a fort and suspected his plans. Clark hired Benjamin O'Fallon to watch Dickson's actions.

Other American Explorations

First Long Expedition

In 1816, the United States planned to build military forts in the region. In July 1817, Major Stephen Harriman Long explored the land Pike had bought in 1805. On July 12, 1817, Long reached Wabasha's village in present-day Winona, Minnesota.

The village was mostly empty because people were out hunting. Long wrote about Chief Wabasha: "The name of their chief is Wauppaushaw, or the Leaf... He is considered one of the most honest & honourable of any of the Indians... He was not at home at the time I called & I had no opportunity of seeing him."

Visits with O'Fallon

In late 1817, several Sioux leaders, including Wabasha, visited American agent Benjamin O'Fallon in Prairie du Chien. Chief Wabasha II showed "strong friendship" to the Americans. He said the British had used "lies" to trick them. O'Fallon promised to send American traders to help them.

In spring 1818, O'Fallon visited Mdewakanton villages. At Wabasha's village, he received a mixed welcome. Chief Wabasha greeted him warmly, but ten elders refused to shake hands and left. Wabasha explained that some elders were still not friendly with the Americans. He also pointed out that American loggers had taken wood from their land without permission.

Forsyth Expedition

In summer 1819, Major Thomas Forsyth, an experienced agent, came from St. Louis. He brought supplies for a future fort and gifts for the Native Americans. These gifts were late payment for the land Pike had bought in 1805.

Forsyth first visited Wabasha's village. He met with Chief Wabasha to talk about the benefits of having a fort nearby. He explained that the new fort would be a place for trade and services like blacksmithing. It would also help stop the Ojibwe from attacking the Dakota. In return, Forsyth asked for safe passage for American boats and an end to tribal warfare. He also warned them not to be tricked by the British again.

Forsyth admired Chief Wabasha II, calling him "Leaf." He gave Wabasha a blanket, tobacco, and powder. Forsyth wrote: "This man is no beggar, nor does he drink, and perhaps I may say he is the only man in the Sioux nation of this description."

Second Long Expedition

In 1823, Major Stephen Harriman Long led another scientific trip. On June 29, 1823, Long reached Wabasha's village. He had a short talk with the chief. Long thought Chief Wabasha II was about fifty years old and very smart. He believed Wabasha was one of the most important Dakota leaders, known more for his wisdom than for fighting. Long described him as "a wise and prudent man, a forcible and impressive orator."

Later, other members of Long's group met Chief Wabasha. They were eager to meet him because he was "held in such high esteem." Wabasha came aboard their boat. He talked about many things, including the benefits of farming and new inventions like the steamboat. He was very interested in how the steamboat worked.

Wabasha also spoke about the ongoing conflict between the Ojibwe and the Dakota. He reminded them of past promises, like building a mill.

Treaties

In spring 1824, Chief Wabasha II went on the "first Sioux Indian delegation to Washington." This trip was organized by American agent Lawrence Taliaferro. Other important Dakota leaders, like Little Crow I, also went. They traveled with a group of Ojibwe. Taliaferro hoped this visit would help end fighting between the Sioux, Ojibwe, and other tribes.

The group traveled by boat from Fort Snelling to Prairie du Chien. Some accounts say Wabasha wanted to turn back after hearing warnings from traders. Other accounts suggest he was convinced to continue to Washington.

In Washington, the Native American groups met with the US Secretary of War and President James Monroe. This meeting helped set the stage for future treaty talks at Prairie du Chien.

1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien

On August 19, 1825, leaders from many Native American tribes gathered at Prairie du Chien. These included the Dakota Sioux, Ojibwe, Sauk, Meskwaki (Fox), Menomonee, Iowa, Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), and Odawa. US officials, including Governor William Clark, were also there.

After long talks, the tribes agreed on boundaries between the Dakota and Ojibwe lands. The treaty also stated there would be "firm and perpetual peace" between the Sioux and other tribes.

Chiefs Wabasha II, Little Crow I, and many other Dakota leaders signed the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien.

However, this treaty did not bring lasting peace. Within months, the tribes went back to fighting. They did not follow the new boundaries. But the treaty did make it easier for the US government to buy land from Native American tribes later on.

1830 Treaty of Prairie du Chien

In summer 1830, another meeting of northwestern tribes happened at Prairie du Chien. US officials William Clark and Colonel Willoughby Morgan were there.

The main goal of this treaty was to stop tribes like the Dakota (Sioux) and the Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) from raiding each other's lands. The US army promised to end tribal warfare. In return, the tribes agreed to punish those who broke the peace. However, it was hard for the army to enforce this.

The US also wanted to gain land in the 1830 treaty. The Dakota gave up a twenty-mile-wide strip of land next to the 1825 border. The Sac and Fox gave up a similar strip. This created a "neutral zone," but it actually caused more problems for hunters from both sides.

The tribes did receive payment for the land. The Dakota would get $2,000 a year for ten years, in money, goods, or animals.

Twenty-six Mdewakantons, including Chiefs Wabasha II and Little Crow I, signed the 1830 Treaty of Prairie du Chien.

Later, agent Lawrence Taliaferro used the $2,000 payment to buy goods for the Dakota. This money helped the Mdewakanton leaders. It showed them that the US government could help with their economic problems, especially as hunting became more difficult.

The treaty also promised a blacksmith. This was very helpful for Wabasha's village. At first, Wabasha protested because the blacksmith shop was too far away. But Agent Taliaferro agreed to put the new shop closer to Kiyuksa village.

Finally, the 1830 treaty set aside a large piece of land (320,000 acres) for the "half-breed relations of the Medawa Kanton Sioux." This land, called the "Half-Breed" Tract, was for mixed-race relatives of the Dakota. Chief Wabasha agreed to discuss land only after the US agreed to give this land to their mixed-race friends.

Black Hawk War

Chief Wabasha II and his band were asked by the United States to fight against Chief Black Hawk and his group of Sauks during the Black Hawk War of 1832.

Peace Talks with the Meskwaki

On May 21, 1832, Chief Wabasha held peace talks with the Dubuque Meskwaki (Fox). The Dakota had complained that Sauk and Meskwaki warriors had entered their territory and killed some of their men. The Meskwaki denied this and said they wanted peace. They smoked and danced together before returning home.

Joining the Fight

In late May, after the US declared war on Black Hawk, General Henry Atkinson asked for the Sioux to help fight. Agent Joseph M. Street sent two men to speak with Chief Wabasha. They reached Wabasha's village on June 1. They found the Sioux "ready to go to war against their old enemies." Within six days, nearly 100 Dakota warriors joined the US forces.

Agent Street had some disagreements with Chief Wabasha and other leaders about how to pay the warriors. Wabasha wanted a single payment to divide among his men, but Street wanted to pay each warrior separately.

Battle of Horseshoe Bend

Wabasha's men, led by a soldier named The Bow, joined Colonel William S. Hamilton. On June 16, 1832, they arrived at the battleground after another group of soldiers had already defeated the Kickapoo warriors.

Leaving the Fight

After a short time, most of the Dakota warriors decided to leave the fight. They turned around and went home. Some were held briefly as deserters. Others went to Prairie du Chien, where Agent Street criticized them for their "cowardice."

Street told The Bow and the Sioux: "You have not hearts to look at the Indians who murdered your families and friends. Go home to your squaws and hoe corn, you are not fit to go to war."

The Bow explained that the Sauk were killing many white people. He also said that Colonel Hamilton had not treated the Native American warriors well and had not given them enough food. Their feet were sore, and they missed their families. Street accused The Bow of lying and sent the Dakota warriors home.

Battle of Bad Axe

Even with the desertions, General Atkinson asked for the Dakota's help again. On August 1, 1832, Captain Joseph Throckmorton went to Wabasha's village to tell them the Sauks were near the Mississippi River and to come quickly. On his way back, Captain Throckmorton found Black Hawk's group and began fighting them.

On August 2, Wabasha and his warriors arrived on the west bank of the river. The Sauk had already been largely defeated. General Atkinson ordered the Sioux to chase the remaining Sauks who were fleeing into Iowa. The Dakota quickly caught up to the Sauks, who were too weak to fight. They attacked and killed at least 68 Sauks.

Black Hawk later criticized the Americans for sending the Sioux to attack the Sauks, including women and children who had escaped. After this devastating loss, the Sauks sought revenge, and fighting continued with the Dakota for another ten years.

Death

Chief Wabasha II died in 1836 during a smallpox epidemic. Many people in his band also died from the disease. On September 10, 1836, Wabasha's band signed a treaty with Colonel Zachary Taylor. This treaty gave up any Sioux claim to land in present-day northwest Missouri. The treaty was signed not by Chief Wabasha II, but by his son, who became Chief Wabasha III.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |