Ojibwe facts for kids

Precontact distribution of Ojibwe-speaking people

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 170,742 in United States (2010) 160,000 in Canada (2014) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Canada (Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta) United States (Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, Montana) |

|

| Languages | |

| English, Ojibwe, French | |

| Religion | |

| Midewiwin, Catholicism, Methodism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Assiniboine, other Algonquian peoples Especially other Anishinaabe, Cree, and Métis |

| Person | Ojibwe |

|---|---|

| People | Ojibweg |

| Language | Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Ojibway, Otchipwe, Ojibwemowin, or Anishinaabemowin |

| Country | Ojibwewaki |

The Ojibwe (also called Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux) are an Anishinaabe people. They live in what is now southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and the Northern Plains. They are Indigenous people from the Subarctic and Northeastern Woodlands regions.

The Ojibwe are one of the largest Native American groups in the United States. In Canada, they are the second-largest First Nations group, after the Cree. They are among the most numerous Indigenous Peoples north of the Rio Grande. About 320,000 Ojibwe people live today. Around 170,742 live in the United States (as of 2010), and about 160,000 live in Canada. In the United States, there are 125 Ojibwe bands. In Canada, they live from western Quebec to eastern British Columbia.

The Ojibwe language is called Anishinaabemowin. It is part of the Algonquian language family.

The Ojibwe are part of the Council of Three Fires. This alliance also includes the Odawa and Potawatomi peoples. They are also part of the larger Anishinaabeg group, which includes the Algonquin, Nipissing, and Oji-Cree people. Historically, the Saulteaux branch of the Ojibwe was part of the Iron Confederacy. This group included the Cree, Assiniboine, and Metis.

The Ojibwe are well-known for their birchbark canoes and birchbark scrolls. They also mined and traded copper. They harvested wild rice and made maple syrup. Their Midewiwin Society is respected for keeping detailed scrolls. These scrolls contain history, songs, maps, stories, and knowledge about geometry and math.

Over time, European powers, Canada, and the United States settled on Ojibwe lands. The Ojibwe signed treaties with these settlers. They gave up some land for settlement. In return, they received payments, land reserves, and promises to keep their traditional rights. Many European settlers then moved into the Ojibwe ancestral lands.

Contents

Language

The Ojibwe language is called Anishinaabemowin or Ojibwemowin. Many people still speak it, but the number of fluent speakers has gone down. Today, most fluent speakers are elders (older people). Since the early 2000s, there has been a strong effort to bring the language back. People want it to be a central part of Ojibwe culture again. The language belongs to the Algonquian language group. It comes from Proto-Algonquian. Other languages like Blackfoot, Cree, and Potawatomi are related to it.

Ojibwemowin is the fourth most spoken Native language in North America. Only Navajo, Cree, and Inuktitut are spoken more. For many years, the fur trade with the French made Ojibwemowin an important trade language. It was used in the Great Lakes and northern Great Plains areas.

The famous poem The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1855) helped make Ojibwe culture known. This poem uses many place names that come from Ojibwe words.

History

Early History and Beliefs

According to Ojibwe oral history and birch bark scrolls, the Ojibwe people started near the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River. This is on the Atlantic coast in what is now Quebec. They traded widely across North America for thousands of years. They knew many canoe routes for travel. The Ojibwe people may have become a distinct group after meeting Europeans. Europeans often preferred to deal with organized groups.

Ojibwe oral history tells of seven great miigis (cowrie shells) that appeared to them. These shells taught them the mide way of life. One miigis was too powerful and returned to the ocean. The other six stayed and taught. They helped establish doodem (clans) for people in the east. These clans were symbolized by animals like the Bullhead, Crane, Pintail Duck, Bear, and Moose.

Later, one of these miigis appeared in a vision. It warned that the Anishinaabeg should move west. This was to keep their traditions alive because many new settlers would arrive in the east. Their journey would be marked by small Turtle Islands. The Anishinaabeg slowly moved west along the Saint Lawrence River to the Ottawa River, then to Lake Nipissing, and finally to the Great Lakes.

Their journey had several "stopping places." The first was Mooniyaa (where Montreal is today). The second was near Niagara Falls. At their third stop, near Detroit, Michigan, the Anishinaabeg split into six groups, and the Ojibwe were one of them.

Their fourth main cultural center was on Manidoo Minising (Manitoulin Island). Their fifth political center was at Baawiting (Sault Ste. Marie). As they moved further west, the Ojibwe split into northern and southern groups. These groups eventually met at their sixth stopping place on Spirit Island in the Saint Louis River estuary (near Duluth/Superior). They were guided to a "place where there is food (wild rice) upon the waters." Their seventh major settlement was at Shaugawaumikong (or Zhaagawaamikong, Chequamegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior.

European Contact and Treaties

The first mention of the Ojibwe in history comes from a French report in 1640. The Ojibwe became friends with French fur traders. This friendship helped them get guns and European goods. They used these to become stronger than their enemies, the Lakota and Fox tribes. They pushed the Sioux from the Upper Mississippi region to the Dakotas. They also forced the Fox from northern Wisconsin.

By the late 1700s, the Ojibwe controlled much of Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota. This included the Red River area. They also controlled the northern shores of lakes Huron and Superior in Canada. Their land stretched west to the Turtle Mountains in North Dakota.

The Ojibwe were part of a long-term alliance called the Council of Three Fires. They fought against the Iroquois Confederacy (from New York) and the Sioux (to the west). The Ojibwe stopped the Iroquois from entering their land near Lake Superior in 1662. They then allied with other tribes like the Huron and Odawa. Together, they pushed the Iroquois out of Michigan and southern Ontario. This helped end the Iroquois Confederacy's power. The Ojibwe then expanded eastward, taking over lands along Lake Huron and Georgian Bay.

In 1745, they got guns from the British. They used these to push the Dakota people further south and west from the Lake Superior area. In the 1680s, the Ojibwe defeated the Iroquois. This victory led to a "golden age" where they ruled southern Ontario without challenge.

Many treaties, called "peace and friendship treaties," were made between the Ojibwe and European settlers. These treaties aimed to share resources. However, the United States and Canada saw these treaties as ways to gain land. The Ojibwe had a different understanding of land. They believed land was a shared resource, like air and water. They could not imagine selling or owning land exclusively. Because of these different views, treaty rights are still debated in courts today.

The Ojibwe allied with the French against Great Britain in the Seven Years' War (also called the French and Indian War). After France lost in 1763, Britain took over French lands in Canada and east of the Mississippi River. After Pontiac's War, the Ojibwe allied with the British against the United States in the War of 1812. They hoped a British victory would protect their land from American settlers.

After the war, the U.S. government tried to force all Ojibwe to move to Minnesota, west of the Mississippi River. The Ojibwe resisted, leading to conflicts. In the Sandy Lake Tragedy, hundreds of Ojibwe died because the government failed to deliver promised payments. Thanks to Chief Buffalo and public support, the Ojibwe east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to reservations on their ceded territory.

In British North America (Canada), the Royal Proclamation of 1763 said that land could only be given up by treaty or purchase. Britain later gave much of Upper Canada to the United States. Even with the Jay Treaty, the U.S. did not fully follow it. Britain gave the U.S. lands in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota and North Dakota. This was to set the border with Canada.

In 1807, the Ojibwe joined three other tribes (Odawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot) to sign the Treaty of Detroit. This agreement gave the United States part of southeastern Michigan and a section of Ohio. The tribes kept small areas of land.

The Battle of the Brule in October 1842 was a fight between the La Pointe Band of Ojibwe and the Dakota. The Ojibwe won this battle in northern Wisconsin.

In Canada, many treaties with the Ojibwe allowed them to keep hunting, fishing, and gathering rights on sold lands. Numbered treaties were signed in northwestern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. British Columbia did not sign many treaties until later. Today, governments and First Nations continue to discuss treaty land rights. Courts often re-interpret old treaties because they are unclear in modern times. The Ojibwe Nation helped set the terms for the first numbered treaties.

Ojibwe communities have a strong history of political action. They were allied with the Odawa and Potawatomi in the Council of the Three Fires. From the 1870s to 1938, the Grand General Indian Council of Ontario tried to unite different traditional groups. In the West, 16 Plains Cree and Ojibwe bands formed the Allied Bands of Qu'Appelle in 1910. They wanted the government to keep its promises from Treaty 4.

Culture

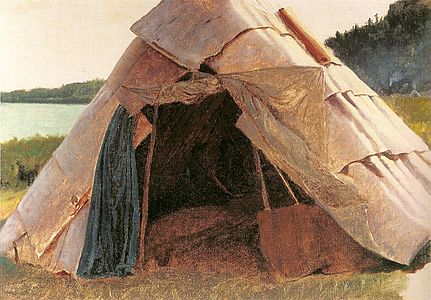

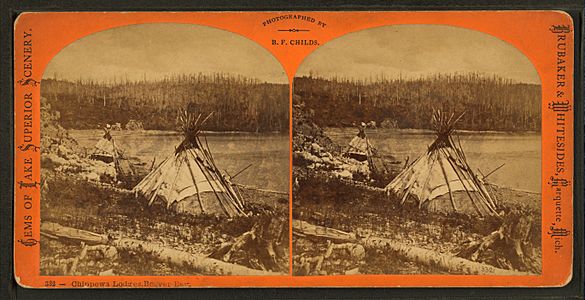

The Ojibwe have traditionally organized themselves into groups called bands. Most Ojibwe, except for those on the Great Plains, lived in one place. They relied on fishing and hunting. They also grew different types of maize (corn) and squash. They harvested manoomin (wild rice) for food. Their traditional homes were wiigiwaam (wigwams). These were dome-shaped or pointed lodges made from birch bark, juniper bark, and willow saplings. Today, most Ojibwe live in modern homes. However, traditional structures are still used for special events.

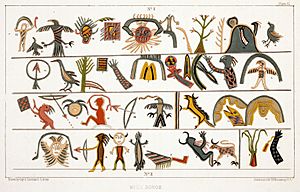

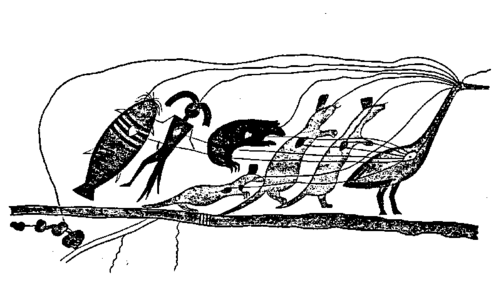

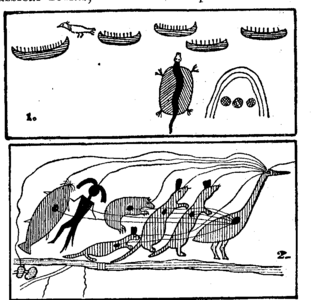

They have a unique way of writing using pictures. This writing was used in the religious ceremonies of the Midewiwin. It was recorded on birch bark scrolls and sometimes on rocks. These complex pictures on sacred scrolls hold historical, geometric, and mathematical knowledge. They also show images from their spiritual beliefs. Petroforms (stone shapes), petroglyphs (rock carvings), and pictographs (rock paintings) were common. Petroforms and medicine wheels taught spiritual ideas, recorded events, and helped remember stories. This picture writing is still used by traditional people and on social media.

Some ceremonies use the miigis shell (cowry shell), which comes from distant coastal areas. This shows that there was a large trade network across North America for a long time. The use and trade of copper also prove a vast trading network that existed for thousands of years. Certain types of rock used for tools were also traded over long distances.

In summer, people attend jiingotamog for spiritual gatherings and niimi'idimaa for social gatherings (powwows). These happen at different reservations in Anishinaabe-Aki (Anishinaabe Country). Many people still follow traditional ways. They harvest wild rice, pick berries, hunt, make medicines, and make maple sugar.

The Ojibwe bury their dead in burial mounds. Many build a jiibegamig or "spirit-house" over each mound. Old burial mounds often had a wooden marker with the deceased's doodem (clan sign). Because of these unique burials, Ojibwe graves were often robbed. In the United States, many Ojibwe communities protect their burial mounds using the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.

Several Ojibwe bands in the U.S. work together in the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission. This group manages treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Lake Superior and Lake Michigan areas. In Michigan, the Chippewa-Ottawa Resource Authority manages hunting, fishing, and gathering rights near Sault Ste. Marie. In Canada, the Grand Council of Treaty No. 3 manages Treaty 3 hunting and fishing rights around Lake of the Woods.

Clothing

Ojibwe clothing was primarily made from materials provided by the natural world, especially animal hides and plant fibers.

- Primary Material: Tanned deer, moose, or elk hide (buckskin). This was soft, durable, and suitable for the northern climate.

- Other Materials: Bear, buffalo (in western regions), and beaver pelts were used for winter robes and blankets. Porcupine quills, moose hair, and later, seeds and shells were used for decoration.

Clothing was designed for mobility and protection in the Great Lakes woodlands—layered for winter, lighter for summer.

Key Garments (Traditional Era)

For Men

- Breechclout (Breechcloth): A long rectangular piece of hide or fabric passed between the legs and fastened over a belt at the waist, with flaps hanging down front and back.

- Leggings: Separate tube-like garments that covered the legs from waist to ankle, tied to the belt. They were essential for protection while traveling through brush.

- Tunic/Shirt: Often made of hide, sometimes sleeveless. In colder weather, a poncho-like shirt or a hide shirt with sleeves was worn.

- Robe or Mantle: A large hide or fur blanket worn over the shoulders in cold weather.

For Women

- Dress: A sleeved, one-piece dress made from two large hide pieces, sewn at the shoulders and sides, often belted at the waist. Styles varied regionally.

- Leggings: Women also wore leggings, but they were typically knee-length and fastened below the knee.

- Robes/Sashes: Similar to men, women used robes for warmth. Woven fiber belts or sashes were common.

Footwear

- Moccasins: Perhaps the most iconic item. Ojibwe moccasins are dsoft-soled, made from a single piece of hide gathered at the top, and often have cuffs. They were often lined with fur in winter.

Outerwear & Winter Gear

- Mittens, Hats, and Hoods: Made from fur or hide.

- Snowshoes: Crucial for winter travel, made from wood and rawhide webbing.

Decoration

Decoration was (and is) profoundly important, carrying artistic, spiritual, and social meaning.

- Porcupine Quillwork: This was the primary decorative art before European contact. Women dyed porcupine quills with natural dyes and intricately sewed them onto hide in geometric patterns (scrolls, flowers, clan symbols). This was a sacred art form.

- Beadwork: After the introduction of glass seed beads by European traders in the mid-19th century, beadwork largely replaced quillwork due to its variety of color and ease of use. Ojibwe floral beadwork is world-renowned—characterized by elegant, flowing floral and vine patterns, often in curves rather than rigid geometry. These designs are not just decorative; they tell stories and represent elements of nature.

Colors and patterns could indicate clan affiliation, regional band, or personal or family symbols.

Modern Context and Cultural Revival

Traditional styles are worn today as regalia for powwows, ceremonies, and other important cultural events. This is a deeply meaningful expression of identity. Ojibwe artists, particularly beadworkers and quillworkers, continue these traditions at the highest level, creating both traditional pieces and contemporary art. Elements like moccasins or beaded jewelry are worn in everyday life, connecting people to their heritage.

Food and Cooking

There is a new interest in healthy eating among the Ojibwe. They are creating more community gardens in areas where healthy food is hard to find. They also have a mobile kitchen to teach about cooking nutritious food. The traditional Native American diet depended on the seasons. It included hunting, fishing, gathering plants, and farming. Today, some modern foods like frybread and "Indian tacos" have replaced traditional meals. Many Ojibwe want to reconnect with their food traditions. This includes using traditional ingredients like wild rice, which is the official state grain of Minnesota. Other main foods were fish, maple sugar, venison (deer meat), and corn. They grew beans, squash, corn, and potatoes. They also gathered blueberries, blackberries, and raspberries. In summer, they hunted animals like deer, beaver, moose, geese, ducks, rabbits, and bears.

One traditional way to make granulated sugar was to boil maple syrup until it was thick. Then, they would pour it into a trough and quickly stir it with wooden paddles to make maple sugar.

Family and Clans

Traditionally, Ojibwe children belonged to their father's clan. This meant that children with French or English fathers were not considered part of an Ojibwe clan unless an Ojibwe man adopted them. They were sometimes called "white" because of their fathers, even if their mothers were Ojibwe.

Ojibwe family relationships are complex. They include immediate and extended family. Siblings and parallel cousins (children of your parent's same-sex sibling) often share the same family terms because they are part of the same clan.

The Ojibwe people were divided into many doodemag (clans). These clans were named mostly after animals and birds, like the Bullhead, Crane, Pintail Duck, Bear, and Moose. The word doodem means "my fellow clansman." The Crane clan was known for speaking out, and the Bear clan was the largest. Each clan had specific duties among the people. People had to marry someone from a different clan.

Each band traditionally had a council. This council included leaders from the community's clans, or odoodemaan. A band was often known by its main doodem. When meeting others, the traditional Ojibwe greeting was, "What is your 'doodem'?" (Aaniin gidoodem? or Awanen gidoodem?). The answer helped people know if they were family, friends, or strangers. Today, the greeting is often shortened to "Aanii" (pronounced "Ah-nee").

Spiritual Beliefs

The Ojibwe have spiritual beliefs passed down through the Midewiwin teachings. These include a creation story and stories about how ceremonies began. Spiritual beliefs and rituals were very important because spirits guided them through life. Birch bark scrolls and petroforms were used to share knowledge and for ceremonies. Pictographs were also used.

The sweatlodge is still used in important ceremonies. During these ceremonies, oral history is shared. Teaching lodges are common today. They teach younger generations about the language and old ways. Traditional ways, ideas, and teachings are kept alive and practiced in these ceremonies.

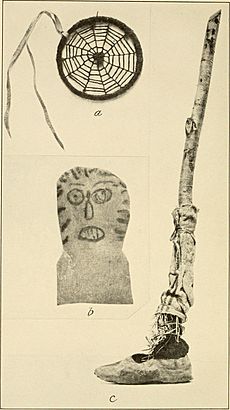

The modern dreamcatcher comes from the Ojibwe "spider web charm." This charm was a hoop with woven string, like a spider's web. It was used to protect babies. According to Ojibwe legend, these charms came from the Spider Woman, Asibikaashi. She cared for children and people. As the Ojibwe Nation spread, it became hard for Asibikaashi to reach all children. So, mothers and grandmothers wove webs for their children. These webs were for protection and were not directly linked to dreams.

Funeral Practices

In Ojibwe tradition, the body is buried quickly, usually the next day. This helps the spirit travel to Gaagige Minawaanigozigiwining, a place of joy and happiness. This journey takes four days. If burial cannot happen right away, guests and medicine men stay with the family. They mourn, sing, and dance through the night. The body is placed with knees to the chest. Food is kept by the grave for four days to feed the spirit. A fire is lit at sunset and kept burning all night. The smoke from the fire guides the spirit. After four days, a feast is held, led by the chief medicine man. He gives away some of the deceased's belongings. Those who receive items give new clothing in return. This new clothing is bundled and given to the closest relative. That person then shares the new clothing with others they believe are worthy.

Today, practices are similar. When someone dies, a fire is lit in the family's home and kept burning for four days. Food and tobacco (a sacred medicine) are offered to the spirit. On the last night, a feast is held, ending with a final smoke or tobacco offering. Modern caskets are used, but birch bark fire starters are buried with the body. These are tools to help light fires to guide the spirit's journey to Gaagige Minawaanigozigiwining.

Plants and Their Uses

The Ojibwe used many plants for food and medicine. For example, they used a plant called Agrimonia gryposepala for urinary problems. They used resin from Pinus strobus (white pine) to treat infections. The roots of Symphyotrichum novae-angliae were smoked to attract game animals. Allium tricoccum (wild leeks) were eaten and used as a quick medicine to cause vomiting. They also used plants for pain relief, to help mothers after childbirth, and for colds. The gum from balsam fir was mixed with bear grease for hair ointment. They also used it to make canoe pitch.

Bands

In his History of the Ojibway People (1855), William W. Warren listed 10 main Ojibwe groups in the United States. He missed some in Michigan, western Minnesota, and all of Canada. When these are added, there are 15 major historical divisions:

| English Name | Ojibwe Name (in double-vowel spelling) |

Location |

|---|---|---|

| Saulteaux | Baawitigowininiwag | Sault Ste. Marie area of Ontario and Michigan |

| Border-Sitters | Biitan-akiing-enabijig | St. Croix-Namekagon River valleys in eastern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin |

| Lake Superior Band | Gichi-gamiwininiwag | south shore of Lake Superior |

| Mississippi River Band | Gichi-ziibiwininiwag | upper Mississippi River in Minnesota |

| Rainy Lake Band | Goojijiwininiwag | Rainy Lake and River, about the northern boundary of Minnesota |

| Ricing-Rails | Manoominikeshiinyag | along headwaters of St. Croix River in Wisconsin and Minnesota |

| Pillagers | Makandwewininiwag | North-central Minnesota and Mississippi River headwaters |

| Mississaugas | Misi-zaagiwininiwag | north of Lake Erie, extending north of Lake Huron about the Mississaugi River |

| Dokis Band (Dokis's and Restoule's bands) | N/A | Along French River (Wemitigoj-Sibi) region (including Little French River (Ziibiins) and Restoule River) in Ontario, near Lake Nipissing |

| Ottawa Lake (Lac Courte Oreilles) Band | Odaawaa-zaaga'iganiwininiwag | Lac Courte Oreilles, Wisconsin |

| Bois Forte Band | Zagaakwaandagowininiwag | north of Lake Superior |

| Lac du Flambeau Band | Waaswaaganiwininiwag | head of Wisconsin River |

| Muskrat Portage Band | Wazhashk-Onigamininiwag | northwest side of Lake Superior at the Canada–US border |

| Nopeming Band | Noopiming Azhe-ininiwag | northeast of Lake Superior and west of Lake Nipissing |

These 15 major divisions led to the Ojibwe Bands and First Nations we see today. Bands are listed under their tribes where possible. See also the listing of Saulteaux communities.

- Aamjiwnaang First Nation

- Aroland First Nation

- Batchewana First Nation of Ojibways

- Bay Mills Indian Community

- Biinjitiwabik Zaaging Anishnabek First Nation

- Burt Lake Band of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians

- Caldwell First Nation

- Chapleau Ojibway First Nation

- Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point

- Chippewas of Lake Simcoe and Huron (Historical)

- Beausoleil First Nation

- Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation

- Chippewas of Rama First Nation (formerly known as Chippewas of Mnjikaning First Nation)

- Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation

- Chippewa of the Thames First Nation

- Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory (Historical)

- Chippewa Cree Tribe of Rocky Boys Indian Reservation

- Curve Lake First Nation

- Cutler First Nation

- Dokis First Nation

- Eabametoong First Nation

- First Nation of Ojibwe California

- Fort William First Nation

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

- Garden River First Nation

- Henvey Inlet First Nation

- Grassy Narrows First Nation (Asabiinyashkosiwagong Nitam-Anishinaabeg)

- Islands in the Trent Waters

- Keeseekoowenin Ojibway First Nation (also known as Riding Mountain Band)

- Koocheching First Nation

- Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation

- Lac La Croix First Nation

- Lac Seul First Nation

- Lake Nipigon Ojibway First Nation

- Lake Superior Chippewa Tribe

- Bad River Chippewa Band

- Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community

- L'Anse Band of Chippewa Indians

- Ontonagon Band of Chippewa Indians

- Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

- Bois Brule River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Chippewa River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

- Removable St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Sokaogon Chippewa Community

- St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians

- Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians

- Magnetawan First Nation

- Minnesota Chippewa Tribe

- Bois Forte Band of Chippewa

- Bois Forte Band of Chippewa

- Lake Vermilion Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Little Forks Band of Rainy River Saulteaux

- Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

- Grand Portage Band of Chippewa

- Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe

- Cass Lake Band of Chippewa

- Lake Winnibigoshish Band of Chippewa

- Leech Lake Band of Pillagers

- Removable Lake Superior Bands of Chippewa of the Chippewa Reservation

- White Oak Point Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Pokegama Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Removable Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe

- Mille Lacs Indians

- Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Rice Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- St. Croix Band of Chippewa Indians of Minnesota

- Kettle River Band of Chippewa Indians

- Snake and Knife Rivers Band of Chippewa Indians

- White Earth Band of Chippewa

- Gull Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Otter Tail Band of Pillagers

- Rabbit Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Removable Mille Lacs Indians

- Rice Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa

- Bois Forte Band of Chippewa

- Mississaugi First Nation

- North Caribou Lake First Nation

- Ojibway Nation of Saugeen First Nation

- Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation

- Osnaburg House Band of Ojibway and Cree (Historical)

- Cat Lake First Nation

- Mishkeegogamang First Nation (formerly known as New Osnaburgh First Nation)

- Slate Falls First Nation

- Pembina Band of Chippewa Indians (Historical)

- Pikangikum First Nation

- Poplar Hill First Nation

- Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians

- Lac des Bois Band of Chippewa Indians

- Rolling River First Nation

- Sagamok Anishnawbek First Nation

- Saginaw Chippewa Tribal Council

- Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians

- Saulteaux First Nation

- Shawanaga First Nation

- Southeast Tribal Council

- Berens River First Nation

- Bloodvein First Nation

- Brokenhead First Nation

- Buffalo Point First Nation (Saulteaux)

- Hollow Water First Nation

- Black River First Nation

- Little Grand Rapids First Nation

- Pauingassi First Nation (Saulteaux)

- Poplar River First Nation

- Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians

- Wabaseemoong Independent Nation

- Wabauskang First Nation

- Wabun Tribal Council

- Beaverhouse First Nation

- Brunswick House First Nation

- Chapleau Ojibwe First Nation

- Matachewan First Nation

- Mattagami First Nation

- Wahgoshig First Nation

- Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation

- Wahnapitae First Nation

- Walpole Island First Nation

- Washagamis Bay First Nation

- Whitefish Bay First Nation

- Whitefish Lake First Nation

- Whitefish River First Nation

- Whitesand First Nation

- Whitewater Lake First Nation

- Wikwemikong Unceded First Nation

Notable Ojibwe People

Here are some notable Ojibwe people. Those from the 20th and 21st centuries are often listed under their specific tribes.

- Taffy Abel (1900-1964), ice hockey player, first Native American in the Winter Olympic Games (1924), first Native American in the National Hockey League (1926), Stanley Cup champion (1929) and (1934)

- Francis Assikinack (1824–1863), historian from Manitoulin Island

- Stephen Bonga, Ojibwe/African-American fur trader and interpreter

- George Bonga (1802–1880), Ojibwe/African-American fur trader and interpreter

- Jeanne L'Strange Cappel (1873–1949), writer, teacher and clubwoman

- Hanging Cloud, 19th c. Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe woman warrior

- George Copway (1818–1869), missionary and writer

- Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom (c.1797–1880), Ojibwe-African American woman in the early Methodist Episcopal Church in Minnesota

- Cara Gee (1983–), Canadian actress

- Fr. Philip B. Gordon (1885–1948), Roman Catholic priest and activist from Gordon, Wisconsin

- Hole in the Day (1825–1868), Chief of the Mississippi Band of the Minnesota Ojibwe

- Michael Hudson (born 1939), economics professor

- Peter Jones (1802–1856), Mississauga missionary and writer

- Kechewaishke (Gichi-Weshkiinh, Buffalo) (ca. 1759–1855), chief

- Edmonia Lewis (ca. 1844–1907), Mississauga Ojibwe/African-American sculptor

- Trixie Mattel (1989–), American drag queen

- Maungwudaus, (1811–1888), performer, interpreter, mission worker, and herbalist

- Medweganoonind, 19th-century Red Lake Ojibwe chief

- T. J. Oshie (1986-), American professional ice hockey player and Stanley Cup champion.

- Ozaawindib (Yellow Head), early 19th c. nonbinary warrior, guide

- Keewaydinoquay Peschel (1919–1999), teacher, ethnobotanist

- Chief Rocky Boy (fl. late 19th c.), chief

- Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (1800–1842), author, wife of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, born in Sault Ste. Marie

- John Smith (ca. 1824–1922, chief, from Cass Lake, Minnesota

- Alfred Michael "Chief" Venne (1879–1971), athletic manager and coach from Leroy, North Dakota

- Waabaanakwad (White Cloud) (ca. 1830–1898), Gull Lake chief

- William Whipple Warren (1825–1853), first historical writer of the Ojibwe people, territorial legislator

- Zheewegonab (fl. 1780–1805), band leader among the northern Ojibwe

Ojibwe Treaties

The Ojibwe have signed many treaties over time. These agreements often dealt with land and rights. Here are some of the important treaties:

- Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority—1836CT fisheries

- Grand Council of Treaty 3—Treaty 3

- Grand Council of Treaty 8—Treaty 8

- Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission—1837CT, 1836CT, 1842CT and 1854CT

- Nishnawbe Aski Nation—Treaty 5 and Treaty 9

- Red Lake Band of Chippewa—1886CT and 1889CT

- Union of Ontario Indians—RS, RH1, RH2, misc. pre-confederation treaties

- La Grande Paix de Montréal (1701)

- Treaty of Fort Niagara (1764)

- Treaty of Fort Niagara (1781)

- Indian Officers' Land Treaty (1783)

- The Crawford Purchases (1783)

- Between the Lakes Purchase (1784)

- Treaty of Peace with Sioux, Chippewa and Winnebago (1787)

- Toronto Purchase (1787)

- Indenture to the Toronto Purchase (1805)

- The McKee Purchase (1790)

- Between the Lakes Purchase (1792)

- Chenail Ecarte (Sombra Township) Purchase (1796)

- London Township Purchase (1796)

- Land for Joseph Brant (1797)

- Penetanguishene Bay Purchase (1798)

- St. Joseph Island (1798)

- Head-of-the-Lake Purchase (1806)

- Lake Simcoe-Lake Huron Purchase (1815)

- Lake Simcoe-Nottawasaga Purchase (1818)

- Ajetance Purchase (1818)

- Rice Lake Purchase (1818)

- The Rideau Purchase (1819)

- Long Woods Purchase (1822)

- Huron Tract Purchase (1827)

- Saugeen Tract Agreement (1836)

- Manitoulin Agreement (1836)

- The Robinson Treaties

- Manitoulin Island Treaty (1862)

- Treaty No. 1 (1871)—Stone Fort Treaty

- Treaty No. 2 (1871)

- Treaty No. 3 (1873)—Northwest Angle Treaty

- Treaty No. 4 (1874)—Qu'Appelle Treaty

- Treaty No. 5 (1875)

- Treaty No. 6 (1876)

- Treaty No. 8 (1899)

- Treaty No. 9 (1905–1906)—James Bay Treaty

- Treaty No. 5, Adhesions (1908–1910)

- The Williams Treaties (1923)

- The Chippewa Indians

- The Mississauga Indians

- Treaty No. 9, Adhesions (1929–1930)

- Treaty of Fort McIntosh (1785)

- Treaty of Fort Harmar (1789)

- Treaty of Greenville (1795)

- Fort Industry (1805)

- Treaty of Detroit (1807)

- Treaty of Brownstown (1808)

- Treaty of Springwells (1815)

- Treaty of St. Louis (1816)—Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi

- Treaty of Miami Rapids (1817)

- Treaty of St. Mary's (1818)

- Treaty of Saginaw (1819)

- Treaty of Saúlt Ste. Marie (1820)

- Treaty of L'Arbre Croche and Michilimackinac (1820)

- Treaty of Chicago (1821)

- First Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825)

- Treaty of Fond du Lac (1826)

- Treaty of Butte des Morts (1827)

- Treaty of Green Bay (1828)

- Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1829)

- Treaty of Chicago (1833)

- Treaty of Washington (1836)—Ottawa & Chippewa

- Treaty of Washington (1836)—Swan Creek & Black River Bands

- Treaty of Detroit (1837)

- Treaty of St. Peters (1837)—White Pine Treaty

- Treaty of Flint River (1837)

- Saganaw Treaties

- Treaty of Saganaw (1838)

- Supplemental Treaty (1839)

- Treaty of La Pointe (1842)—Copper Treaty

- Isle Royale Agreement (1844)

- Treaty of Potawatomi Creek (1846)

- Treaty of Fond du Lac (1847)

- Treaty of Leech Lake (1847)

- Treaty of La Pointe (1854)

- Treaty of Washington (1855)

- Treaty of Detroit (1855)—Ottawa & Chippewa

- Treaty of Detroit (1855)—Sault Ste. Marie Band

- Treaty of Detroit (1855)—Swan Creek & Black River Bands

- Treaty of Sac and Fox Agency (1859)

- Treaty of Washington (1863)

- Treaty of Old Crossing (1863)

- Treaty of Old Crossing (1864)

- Treaty of Washington (1864)

- Treaty of Isabella Reservation (1864)

- Treaty of Washington (1866)

- Treaty of Washington (1867)

Gallery

-

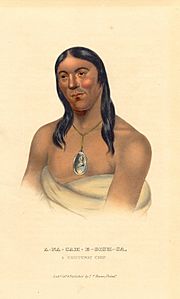

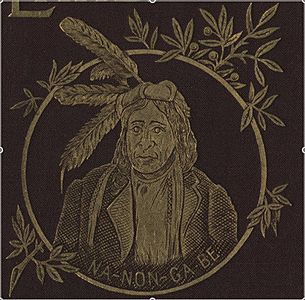

A-na-cam-e-gish-ca (Aanakamigishkaang/"[Traces of] Foot Prints [upon the Ground]"), Ojibwe chief, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

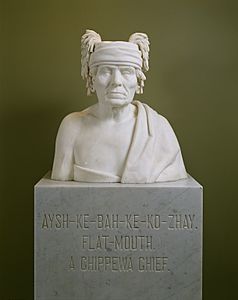

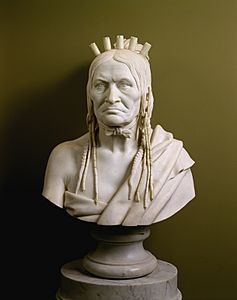

Bust of Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay (Eshkibagikoonzhe or "Flat Mouth"), a Leech Lake Ojibwe chief

-

Chief Beautifying Bird (Nenaa'angebi), by Benjamin Armstrong, 1891

-

Bust of Beshekee, war chief, modeled 1855, carved 1856

-

Caa-tou-see, an Ojibwe, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Hanging Cloud, a female Ojibwe warrior

-

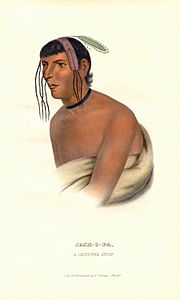

Jack-O-Pa (Zhaagobe/"Six"), a St. Croix Ojibwe chief, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

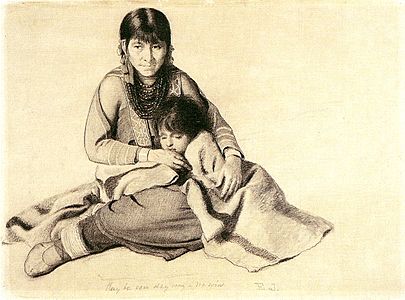

Kay be sen day way We Win, by Eastman Johnson, 1857

-

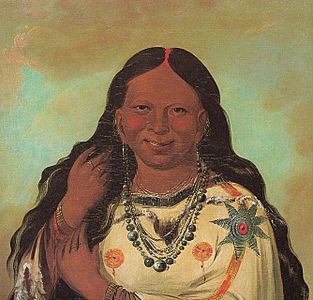

Kei-a-gis-gis, a Plains Ojibwe woman, painted by George Catlin

-

"One Called From A Distance" (Midwewinind) of the White Earth Band, 1894.

-

Pee-Che-Kir, Ojibwe chief, painted by Thomas Loraine McKenney, 1843

-

Ojibwe chief Rocky Boy

-

Ojibwe woman and child, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Tshusick, an Ojibwe woman, from History of the Indian Tribes of North America

-

Wildfire, English name Edmonia Lewis

-

Details of Ojibwe Wigwam at Grand Portage by Eastman Johnson, c. 1906

-

Pictographs on Mazinaw Rock, Bon Echo Provincial Park, Ontario

See also

In Spanish: Ojibwa para niños

In Spanish: Ojibwa para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |