Kechewaishke facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kechewaishke (Great Buffalo)

|

|

|---|---|

Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society

|

|

| Born | c.1759 |

| Died | September 7, 1855 La Pointe

|

| Nationality | Ojibwe |

| Other names | Bizhiki (Buffalo) |

Chief Buffalo (in Ojibwe: Ke-che-waish-ke or Peezhickee, meaning "Great-renewer" or "Buffalo") was an important Ojibwe leader. He was born around 1759 in La Pointe, located in the Apostle Islands of Lake Superior, in what is now northern Wisconsin, USA.

Chief Buffalo was the main leader of the Lake Superior Chippewa (Ojibwe) for almost 50 years, until his death in 1855. He helped his people create agreements, called treaties, with the United States Government. He signed treaties in 1825, 1826, 1837, 1842, 1847, and 1854. He played a key role in stopping the U.S. from moving the Ojibwe people to western areas. Thanks to him, his people got permanent reservations near Lake Superior in Wisconsin.

Contents

Chief Buffalo's Early Life and People

The Ojibwe Way of Life

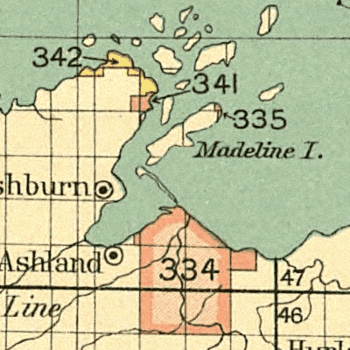

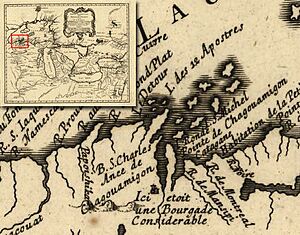

Kechewaishke, also known as Chief Buffalo, was born around 1759. His birthplace was La Pointe on Madeline Island. This area was a major Ojibwe village and a busy trading spot. At that time, New France controlled the area and was fighting Great Britain.

During the 1700s, the Ojibwe people spread out from La Pointe. They moved into lands they had gained from the Dakota people. Many Ojibwe villages were started. The Ojibwe bands in the western Lake Superior and Mississippi River areas saw La Pointe as their "ancient capital." It was also a spiritual and trading hub.

Traditional Ojibwe society was built around family groups called clans. Each clan had a special animal symbol, known as a doodem. Each doodem had a specific role within the tribe. Chief Buffalo belonged to the Loon clan.

The Loon Clan became more important in the mid-1700s. This was thanks to Chief Buffalo's grandfather, Andaigweos. Andaigweos was a skilled speaker and was well-liked by French officials. While the Crane clan traditionally held positions as peace chiefs, by the 1800s, the Loon clan, led by Chief Buffalo, was recognized as the main chiefs at La Pointe.

A chief's power in Ojibwe society came from convincing people and getting everyone to agree. A chief's leadership lasted only as long as the elders and community chose to follow them.

Chief Buffalo's Personal Journey

Not much is known about Chief Buffalo's early life. When he was about 10, his family moved to what is now Buffalo, New York. They lived there for about two years. Later, they moved to the Mackinac Island area before returning to La Pointe. When he was young, Chief Buffalo was known as a great hunter and athlete.

Chief Buffalo was also known by another Ojibwe name, Peshickee, which means "the Buffalo." This caused some confusion in historical records. There were other important leaders with similar names.

Chief Buffalo practiced the Midewiwin religion. He converted to Roman Catholicism just before he died.

Chief Buffalo's Approach to Peace

Chief Buffalo was known for using peaceful methods in his dealings with the United States. He often disagreed with U.S. policies toward Native Americans. He was different from other Ojibwe chiefs who fought wars against the Dakota Sioux.

Some records suggest Chief Buffalo won a big victory against the Dakota in the 1842 Battle of the Brule. However, later historians have questioned this story. In 1842, Chief Buffalo was quoted saying he "never took a scalp in his life." He added that he had taken prisoners whom he "fed and well-treated." He seemed to support peace between the Ojibwe and Dakota.

Chief Buffalo was respected for his speaking skills, which were highly valued in his culture. By the time the Ojibwe of Wisconsin and Minnesota began treaty talks with the U.S. Government, Chief Buffalo was seen as a main spokesperson for all the Ojibwe bands.

Treaties of 1825 and 1826: Setting Boundaries

In 1825, Chief Buffalo was one of 41 Ojibwe leaders to sign the First Treaty of Prairie du Chien. His name was recorded as "Gitspee Waishkee" or La Boeuf. This treaty aimed to end fighting between the Dakota and their neighbors. It asked all Native American tribes in Wisconsin and Iowa to mark their territory boundaries. The U.S. used this information to later gain Native American lands.

A year later, the U.S. and Ojibwe signed the Treaty of Fond du Lac. Chief Buffalo, recorded as Peezhickee, signed as the first chief from La Pointe. This treaty mainly dealt with mineral rights on Ojibwe lands in Michigan. Chief Buffalo did not discuss the copper issue. He praised U.S. officials for controlling their young people. When he was given a silver medal as a symbol of his leadership, Chief Buffalo said his power came from his clan and reputation, not from the U.S. government.

After these treaties, U.S. Indian agent Henry Schoolcraft visited La Pointe. He criticized Chief Buffalo for not stopping the ongoing fights between the Ojibwe and Dakota. Chief Buffalo explained that he could not control all the young men from other Ojibwe bands. He also said the U.S. government had not done enough to keep peace among the tribes.

Treaties of 1837 and 1842: Land and Resources

In the following decades, Americans wanted to use the timber and mineral resources on Ojibwe lands. The U.S. government tried to get control of these lands through new treaties. The Treaties of 1837 and 1842 covered La Pointe and other lands where Chief Buffalo had a lot of influence. In both treaties, Americans recognized him as the main chief of all the Lake Superior Ojibwe.

The "Pine Tree" Treaty of 1837

In the Treaty of St. Peters (1837), the government wanted pine timber from Ojibwe lands. The talks happened near present-day Minneapolis. Other chiefs waited for Chief Buffalo's decision before agreeing to the treaty. Even though the governor was impatient, the talks were delayed for five days until Chief Buffalo arrived.

Chief Buffalo spoke about how mixed-blood traders should be paid. He said, "I am an Indian and do not know the value of money, but the half-breeds do, for which reason we wish you pay them their share in money." He wanted things to be fair for everyone.

Once terms were agreed, Chief Buffalo signed as Pe-zhe-ke, the head of the La Pointe group. He later wrote to Governor Dodge about his concerns. He said, "The Indians acted like children; they tried to cheat each other and got cheated themselves." He also said, "When it comes my turn to sell my land, I do not think I shall give it up as they did."

The "Copper" Treaty of 1842

Five years later, Chief Buffalo faced the Treaty of La Pointe. This treaty covered his lands and aimed to develop the copper industry. There are no official records of the talks. However, accounts from missionaries and traders suggest that U.S. officials used strong tactics to make the Ojibwe accept the terms.

Chief Buffalo signed as Gichi waishkey, the first chief of La Pointe. But three months later, he sent a letter to the government in Washington D.C.. He said he was "ashamed" of how the treaty was handled. He explained that officials refused to listen to the Ojibwe's concerns. He asked to add a rule to ensure permanent Ojibwe reservations in Wisconsin.

The meaning of the 1837 and 1842 treaties is still debated. The U.S. government claimed the Ojibwe gave up ownership of the lands. But the Ojibwe believed they only gave up rights to resources. The Ojibwe did get yearly payments at La Pointe. They also kept the right to hunt, fish, gather, and move across the lands. They were promised they would not be moved across the Mississippi River unless they "misbehaved."

Facing Threats of Removal

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. This law allowed the government to move Native American nations east of the Mississippi River to the west. The Ojibwe were not immediately targeted. However, they watched as other tribes were forced to move west. These included the Odawa and Potawatomi, who were related to the Ojibwe.

In 1848, Wisconsin became a state. This put more pressure on Native American nations to be moved. Corrupt U.S. agents controlled payments to tribes. They sometimes underpaid tribes and let white settlers move onto Ojibwe lands. The Ojibwe complained about this unfair treatment. But politicians often listened more to land speculators who wanted to profit from moving the Ojibwe.

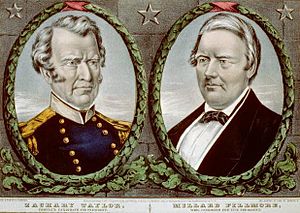

Even with the treaties, Ojibwe leaders worried about being moved. Chief Buffalo stayed in touch with other bands. He sent messengers to report any behavior that could be used as an excuse for removal. No such behavior was reported. But President Zachary Taylor signed a removal order on February 6, 1850. He claimed it was to protect the Ojibwe from "injurious" whites. The Wisconsin government resisted this order. However, the governor of Minnesota and an Indian agent planned to force the Ojibwe to Minnesota anyway.

The Sandy Lake Tragedy

To force the Ojibwe to move, the agent announced that future payments would only be made at Sandy Lake, Minnesota. Previously, payments were made at La Pointe. This change led to the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Hundreds of Ojibwe people starved or died from cold on the journey. The promised supplies were late, spoiled, or not enough.

Chief Buffalo later described the terrible conditions:

And when a message was sent to me by our Indian agent to come and get our pay, I lost no time in arising & complying with my Agents voice and when I reached my point of destination, verily my Agent fed me with very bad flour it resembled green clay. Soon I became sick and many of my fellow chippewas also were taken sick, and soon the results were manifested by the death of over two hundred persons of my tribe, for this calamity, I laid blame to the provisions issued to us...

Back in La Pointe, Chief Buffalo took action to stop the removal. He and other leaders asked the U.S. government for help. They gained sympathy from white people who heard about the disaster at Sandy Lake. Newspapers in the Lake Superior region wrote articles against the removal plan. Chief Buffalo sent two of his sons to St. Paul to get some of the payments still owed.

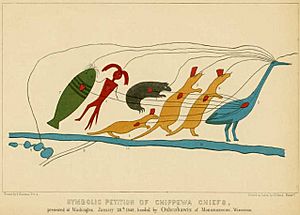

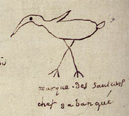

The governor of Minnesota and the agent continued trying to move the Ojibwe. Young Ojibwe men in Wisconsin were very angry. There was a growing threat of violent revolt. Chief Buffalo asked his sub-chief Oshoga and his son-in-law Benjamin G. Armstrong for help. Armstrong was a white interpreter married to Chief Buffalo's daughter. Chief Buffalo created a petition. The 92-year-old Chief Buffalo personally delivered it to the president in Washington.

A Journey to Washington

In the spring of 1852, Chief Buffalo, Oshoga, Armstrong, and four others traveled from La Pointe to Washington, D.C. They went by birchbark canoe. Along the way, they stopped in towns and mining camps. They collected hundreds of signatures supporting their cause.

At Sault Ste. Marie, a U.S. Indian agent tried to stop them. He said no unauthorized Ojibwe groups could go to Washington. But the men explained how urgent their case was. They traveled to Detroit by steamship. Another agent tried to stop them there too. Once allowed to continue, they sailed through Lake Erie to Buffalo, New York, and then to Albany and New York City.

In New York City, the Ojibwe gained public attention and money for their trip. But in Washington, the Bureau of Indian Affairs turned them away. They were told they should not have come. Luckily, they met Congressman Briggs from New York. He had a meeting with President Millard Fillmore the next day. He invited the Ojibwe to come with him.

At the meeting, Chief Buffalo spoke first. He performed a pipe ceremony with a special pipe. Oshoga then spoke for over an hour about the broken treaty promises and the terrible removal attempt. President Fillmore agreed to look into the issues. The next day, he announced that the removal order would be canceled. Payments would return to La Pointe. Also, a new treaty would create permanent reservations for the Ojibwe in Wisconsin.

The group traveled back to Wisconsin by train. They shared the good news with the different Ojibwe bands. Chief Buffalo also announced that all tribal representatives should gather at La Pointe the next summer (1853) for payments. He would then share the details of the agreement.

The 1854 Treaty and Chief Buffalo's Land

As President Fillmore promised, treaty officials arrived in La Pointe in 1854. They came to finalize a new treaty. Ojibwe leaders wanted to control the talks this time. Chief Buffalo insisted that only his adopted son, Armstrong, could be the interpreter. The Ojibwe demanded the right to hunt, fish, and gather on all the lands they were giving up. They also wanted several reservations in northern Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and northeastern Minnesota.

Chief Buffalo was in his mid-nineties and not in good health. He guided the talks but let other chiefs do most of the speaking. He trusted Armstrong with the written details of the agreement.

The reservations created in Wisconsin were the Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservation and Lac du Flambeau Indian Reservation. The La Pointe Band received a reservation at Bad River. This was near their traditional wild rice gathering areas. They also got some land for fishing at Madeline Island. Reservations were also set up in Minnesota and Michigan for other Ojibwe bands.

A small piece of land was also set aside for Chief Buffalo and his family. This was at Buffalo Bay on the mainland, across from Madeline Island. Many Catholic and mixed-blood members of the La Pointe Band chose to settle there with Chief Buffalo. In 1855, this settlement was recognized. It was later expanded into what is now the Red Cliff Indian Reservation.

Death and Lasting Impact

Chief Buffalo was too ill to speak during the annuity payments in the summer of 1855. Tensions continued, with the Ojibwe accusing U.S. officials of corruption. These conflicts made Chief Buffalo's health worse. He died of heart disease on September 7, 1855, in La Pointe. Members of his band blamed his death on the actions of government officials.

Chief Buffalo was described as the "head and the chief of the Chippewa Nation." He was respected for his honesty, wisdom, powerful speeches, and bravery as a warrior. In his final hours, he asked that his tobacco pouch and pipe be taken to Washington, D.C., and given to the government. His funeral was held with military honors.

Chief Buffalo is seen as a hero of the Lake Superior Ojibwe. The people at Red Cliff also remember him as a founder of their community. His life is celebrated during events that remember the treaty signings and the Sandy Lake Tragedy. He is buried in the La Pointe Indian Cemetery, near the deep waters of Lake Superior. His descendants, many with the last name "Buffalo," live in Red Cliff and Bad River today.

Starting in 1983, during conflicts over treaty rights known as the Wisconsin Walleye War, Chief Buffalo's name was often mentioned. He was remembered as someone who refused to give up his homeland and his people's right to govern themselves.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |