Treaty of St. Peters facts for kids

The Treaty of St. Peters refers to two important agreements between the United States and Native American groups. These treaties happened where the Minnesota River meets the Mississippi River. This area is now Mendota, Minnesota.

Contents

1805 Treaty of St. Peters

The 1805 Treaty of St. Peters is also known as Pike's Purchase. It was an agreement between Lieutenant Zebulon Pike for the United States and Chiefs "Le Petit Carbeau" and Way Aga Enogee from the Sioux Nation. This treaty was signed on September 23, 1805.

It involved the purchase of two areas of land. Each area was nine square miles. One was near the St. Croix River, close to what is now Hastings, Minnesota. The other was where the Minnesota River meets the Mississippi River, near today's Mendota, Minnesota. The goal was to build military bases in these spots.

A military base was not built near the St. Croix River. However, Fort Snelling was built on the hills overlooking where the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers meet. Even though the President of the United States never officially announced this treaty, the United States Congress approved it on April 16, 1808.

1837 Treaty of St. Peters

The 1837 Treaty of St. Peters is also called the Treaty with the Chippewa or the White Pine Treaty. This agreement was made between Governor Henry Dodge for the United States and leaders from Ojibwa groups. These groups lived in areas that are now Wisconsin and Minnesota.

The treaty was signed on July 29, 1837, in St. Peters, Wisconsin Territory. This place is known today as Mendota, Minnesota. The tribes who signed this treaty often call it The Treaty of 1837. The treaty became official on June 15, 1838.

Land Cession Terms

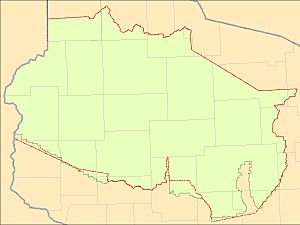

In this treaty, the Ojibwa nations gave a large area of land to the United States. This land stretched from the Mississippi River in east-central Minnesota to the Wisconsin River in northern Wisconsin. The southern border followed a line set by an earlier treaty in 1825. The northern border was the area where water flows into Lake Superior.

The United States wanted this land to get lumber from the Wisconsin Territory. This lumber was needed to build homes for the growing populations in cities like St. Louis, Missouri and Cleveland, Ohio. In return for the land, the United States promised to pay the Ojibwa groups for twenty years. They also made special plans for the Metis people in the area.

The Ojibwa groups who signed the treaty kept their usufructuary rights. This means they could still hunt, fish, and gather resources on the land they had given up.

Signatories

| # | Location | Recorded Name | Name (Translation/"Alias") | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Leech Lake | Aish-ke-bo-ge-koshe | Eshkibagikoonzhe (Flat Mouth) | Chief |

| 02 | Leech Lake | R-che-o-sau-ya | Gichi-osayenh (Elder Brother) | Chief |

| 03 | Leech Lake | Pe-zhe-kins | Bizhikiins (Young Buffalo) | Warrior |

| 04 | Leech Lake | Ma-ghe-ga-bo | Nayaajigaabaw ("la Trappe") | Warrior |

| 05 | Leech Lake | O-be-gwa-dans | (Chief of the Earth) | Warrior |

| 06 | Leech Lake | Wa-bose | Waabooz (Rabbit) | Warrior |

| 07 | Leech Lake | Che-a-na-quod | Chi-aanakwad (Big Cloud) | Warrior |

| 08 | Gull Lake and Swan River | Pa-goo-na-kee-zhig | Bagone-giizhig (Hole in the Day) | Chief |

| 09 | Gull Lake and Swan River | Songa-ko-mig | Zoongakamig (Strong Ground) | Chief |

| 10 | Gull Lake and Swan River | Wa-boo-jig | Waabojiig (White Fisher) | Warrior |

| 11 | Gull Lake and Swan River | Ma-cou-da | Makode' (Bear's Heart) | Warrior |

| 12 | St. Croix River | Pe-zhe-ke | Bizhikiinh (Buffalo) | Chief |

| 13 | St. Croix River | Ka-be-ma-be | Gaa-bimabi (He that sits to the side/"Wet mouth") | Chief |

| 14 | St. Croix River | Pa-ga-we-we-wetung | Bigiiwewewidang (Coming Home Hollering) | Warrior |

| 15 | St. Croix River | Ya-banse | Ayaabens (Young Buck) | Warrior |

| 16 | St. Croix River | Kis-ke-ta-wak | Giishkitawag (Cut Ear) | Warrior |

| 17 | Lac Courte Oreilles Band | Pa-qua-a-mo | Bakwe'aamoo (Woodpecker) | Chief |

| 18 | Lac du Flambeau Band | Pish-ka-ga-ghe | Apishkaagaagi (Magpie/"White Crow") | Chief |

| 19 | Lac du Flambeau Band | Na-wa-ge-wa | (Knee) | Chief |

| 20 | Lac du Flambeau Band | O-ge-ma-ga | Ogimaakaanh (Dandy) | Chief |

| 21 | Lac du Flambeau Band | Pa-se-quam-jis | (Commissioner) | Chief |

| 22 | Lac du Flambeau Band | Wa-be-ne-me | Waabanimikii (White Thunder) | Chief |

| 23 | La Pointe Band | Pe-zhe-ke | Bizhiki (Buffalo) | Chief |

| 24 | La Pointe Band | Ta-qua-ga-na | Dagwagaane (Two Lodges Meet) | Chief |

| 25 | La Pointe Band | Cha-che-que-o | Jechiikwii'o (Snipe) | Chief |

| 26 | Mille Lacs Indians | Wa-shask-ko-kone | Wazhashkokon (Muskrat's Liver) | Chief |

| 27 | Mille Lacs Indians | Wen-ghe-ge-she-guk | Wenji-giizhigak (First Day) | Chief |

| 28 | Mille Lacs Indians | Ada-we-ge-shik | Edawi-giizhig (Both Ends of the Sky) | Warrior |

| 29 | Mille Lacs Indians | Ka-ka-quap | Gekekwab ([Sitting on a] Sparrow[hawk]) | Warrior |

| 30 | Sandy Lake Band | Ka-nan-da-wa-win-zo | Gaa-nandawaawinzo (Ripe-Berry Hunter/"le Brocheux") | Chief |

| 31 | Sandy Lake Band | We-we-shan-shis | Gwiiwizhenzhish (Bad Boy/"Big Mouth") | Chief |

| 32 | Sandy Lake Band | Ke-che-wa-me-te-go | Gichi-wemitigo (Big Frenchman) | Chief |

| 33 | Sandy Lake Band | Na-ta-me-ga-bo | Netamigaabaw (Stands First) | Warrior |

| 34 | Sandy Lake Band | Sa-ga-ta-gun | Zagataagan (Spunk) | Warrior |

| 35 | Snake River | Naudin | Noodin (Wind) | Chief |

| 36 | Snake River | Sha-go-bai | Zhaagobe ("Little" Six) | Chief |

| 37 | Snake River | Pay-ajik | Bayezhig (Lone Man) | Chief |

| 38 | Snake River | Na-qua-na-bie | Negwanebi ([Tallest Quill-]Feather) | Chief |

| 39 | Snake River | Ha-tau-wa | Odaawaa (Trader/"Ottawa") | Warrior |

| 40 | Snake River | Wa-me-te-go-zhins | Wemitigoozhiins (Little Frenchman) | Warrior |

| 41 | Snake River | Sho-ne-a | Zhooniyaa (Silver) | Warrior |

| 42 | Fond du Lac Band | Mang-go-sit | Maangozid (Loon's Foot) | Chief |

| 43 | Fond du Lac Band | Shing-go-be | Zhingobiinh (Spruce) | Chief |

| 44 | Red Cedar Lake | Mont-so-mo | (Murdering Yell) | |

| 45 | Red Lake | Francois Goumean | François Gourneau | half breed |

| 46 | Leech Lake | Sha-wa-ghe-zhig | Zhinawaagiizhig ([Re]sounding Sky) | Warrior |

| 47 | Leech Lake | Wa-zau-ko-ni-a | Wezaawikonaye (Yellow Robe) | Warrior |

The people involved in the treaty included:

- Commissioner: Henry Dodge

- Recording Secretary: Verplanck Van Antwerp

- Indian Agents:

- Lawrence Taliaferro

- Miles M. Vineyard

- Daniel P. Bushnell

- Interpreters:

- John Baptiste DuBay

- Peter Quinn

- Scott Campbell

- Stephen Bonga

- Army:

- Martin Scott, Captain

- Dr. John Emerson, Assistant Surgeon

- Traders:

- Hercules L. Dousman

- Henry Hastings Sibley

- Lyman Marquis Warren

- Special guests:

Establishment of Reservations

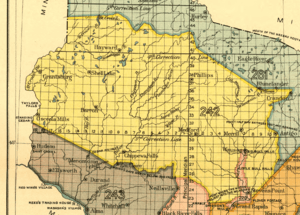

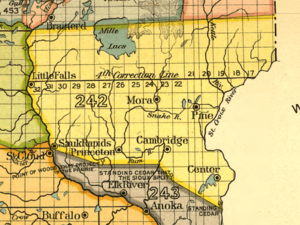

The land given up in the 1837 treaty, along with land from treaties in 1842 and 1854, helped decide where Indian Reservations would be located. This was done in the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe and the 1855 Treaty of Washington.

Charles Royce called this area "Land Cession Area No. 242" in his 1899 report. So, it's often known as "Royce Area 242." This area was planned to have five zones, each with a proposed reservation of about 60,000 acres. These were for Mille Lacs Lake, St. Croix, Lac Courte Oreilles, Lac du Flambeau, and Mole Lake. There were also plans for Fond du Lac, La Pointe, and Lac Vieux Desert.

However, the St. Croix and Sokoagon groups left the talks for the 1854 Treaty of La Pointe. Because of this, they lost their official recognition from the government until 1934. The planned St. Croix and Mole Lake reservations were never created.

For St. Croix, their Chief Ayaabens became ill. The United States would not accept a sub-Chief to negotiate, even if they had the power to do so. So, the St. Croix group had to leave the talks. Their oral history says that if the Chief hadn't been sick, they would have pushed to keep their treaty rights for hunting, fishing, and gathering outside the reservation. Chief Ayaabens died shortly after.

For Mole Lake, their Chief was not allowed at the treaty meeting. The United States believed that the smaller reservations they first offered (about 10,000 acres each) were not good enough compared to a single 60,000-acre reservation. The Mole Lake Chief sent his sub-Chief, who had full power to negotiate. But like St. Croix, the United States would not accept the sub-Chief. This left the Mole Lake group no choice but to leave.

Despite these issues, the Mille Lacs Lake and Lac Courte Oreilles Indian Reservations were created. The Lac du Flambeau Indian Reservation was also created, covering parts of both the 1837 and 1842 treaty lands.

Treaty area boundary adjustments

In Wisconsin, the southern borders of the 1837 treaty area have been changed to follow clear landmarks like roads and streams. However, in Wisconsin, members of the Ojibwa groups can still hunt, fish, and gather on all treaty lands. They need permission from the property owner and a license from their tribe.

In Minnesota, the borders have not been changed. However, hunting is only allowed on public lands within the 1837 treaty area and requires a tribal hunting license. On private lands within the treaty area, state hunting licenses and rules apply. For fishing and gathering in Minnesota's part of the 1837 treaty area, tribal licenses are needed.

1851 Treaty of St. Peters

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |