Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom

|

|

|---|---|

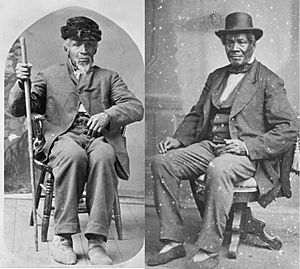

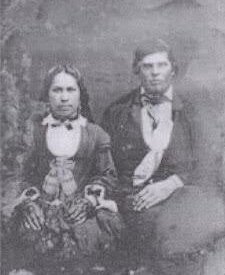

Margaret with Jacob Fahlstrom

|

|

| Born | c.1797 Fond du Lac (Duluth), Lake Superior

|

| Died | February 6, 1880 Afton, Washington County, Minnesota

|

| Nationality | Ojibwe, French African ancestry |

| Other names | Marguerite Bonga Margaret Bungo Margaret Falstrom Margaret Folstrom |

| Spouse(s) | Jacob Fahlstrom (m.1823) |

| Relatives | Pierre Bonga (father) George Bonga (brother) Stephen Bonga (brother) |

Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom (born around 1797 – died February 6, 1880) was an amazing woman from a fur trading family. She had both African and Ojibwe heritage.

In 1823, Margaret married Jacob Fahlstrom, who was the first Swedish settler in Minnesota. They lived on a small farm near Fort Snelling. Margaret was one of the few free Black women in the area. At that time, many Black people were enslaved, like Harriet Robinson Scott, who fought for her freedom.

In 1838, the Fahlstroms became the first people in Minnesota to join the Methodist church. They moved to a farm in Washington County in 1840. Jacob became a famous Methodist preacher, known as "Father Jacob." People said his success came from speaking the Ojibwe language well and from his marriage to Margaret. Margaret and her daughters were also important in early church meetings. They often welcomed traveling Methodist preachers into their home.

A historian named W.H.C. Folsom wrote in 1888 that Margaret had a "fine mind." He said very few people of any age or background could be her equal. Margaret and Jacob were married for 35 years and had nine children. They eventually settled in Afton, Minnesota, where Margaret is buried next to her husband.

Contents

Margaret's Family and Early Life

Margaret Bonga was born around 1797 near Lake Superior. Her parents were Pierre Bonga, a Black fur trader, and his Ojibwe wife, Ojibwayquay. Pierre was baptized as a Catholic in Montreal. The Bonga children grew up speaking French, Ojibwe, and English. This showed their mixed cultural background.

The Bonga Family Story

Margaret's grandparents, Jean and Marie-Jeanne Bonga, ran a popular tavern on Mackinac Island in Michigan. They spoke French. They arrived in Michilimackinac in the early 1780s as enslaved people from the Caribbean. From 1782 to 1787, they were enslaved by Captain Daniel Robertson, a British Army officer. In 1787, Captain Robertson freed Jean, Marie-Jeanne, and their four children. Then he returned to Montreal.

It's not fully clear how the Bonga family came to Mackinac. Some say they were captured during the American Revolutionary War and sold as slaves to Captain Robertson. Others think Robertson brought them to the fort himself.

Pierre Bonga's Fur Trade Career

Pierre Bonga, Margaret's father, became a very successful fur trader. He started as a helper and middleman. Later, he became a voyageur (a traveler who transported furs) and an interpreter. He worked for the North West Company and then the American Fur Company.

Pierre worked with fur trader John Sayer near Fond du Lac as early as 1795. From 1802 to 1806, he worked with Alexander Henry the Younger in the Red River area.

Margaret's Ojibwe Mother

Pierre likely met his wife, Ojibwayquay, while working at Fond du Lac. Her name means "Ojibwe woman." They were married à la façon du pays, which was a traditional way of marrying among fur traders and Native American women. She was from an Ojibwe group near Lake Superior.

Margaret was born at Fond du Lac (Duluth) in 1797. Her Ojibwe name might have been Kahjiji. In 1802, Ojibwayquay traveled with Pierre to a fur trade post. It's not known if their other children went with them or stayed with relatives.

Margaret's Siblings

Margaret's most well-known brothers were George Bonga and Stephen Bonga. They also worked in the fur trade. Stephen and their oldest brother, Jean-Baptiste, started working for fur companies at a young age. Margaret likely had two sisters born between George and Stephen. Their youngest brother, Jack, was born around 1815.

The family stayed in touch with their Bonga relatives who moved to Montreal. Stephen, George, and their sister Blanche were baptized in the Catholic Church in Montreal in 1810 and 1811. George even went to school there.

In 1820, explorer Henry Schoolcraft met Pierre Bonga and his family at Fond du Lac. Schoolcraft wrote that the children were as dark-skinned as their father, with curly hair.

Margaret Marries Jacob Fahlstrom

Margaret Bonga married Jacob Fahlstrom in 1823 at Fond du Lac. Jacob is often called "the first Swede in Minnesota." He had worked in the fur trade for over ten years. He spoke English, French, Ojibwe, Iroquois, and Dakota, besides his native Swedish. The Ojibwe called Jacob "Ozaawindib," meaning "Yellow Head," because of his blond hair.

There isn't much information about their wedding. A Methodist missionary named Alfred Brunson later met the Fahlstroms. He wrote that Jacob married Margaret "in good faith," not just for a short time like some traders.

Jacob Fahlstrom's Background

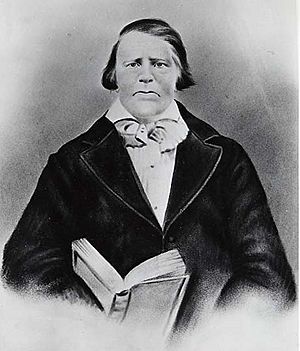

Jacob was born in Stockholm, Sweden, around 1794. He reportedly left Sweden on a ship with his uncle and may have been shipwrecked. In 1811, he joined the Hudson's Bay Company and traveled to Canada. After his training, he briefly worked for the North West Company. Then he joined the American Fur Company.

He worked for the American Fur Company for seven years. From 1819 to 1822, he was a boatman in Duluth. He traveled through Minnesota to trade with tribes. He was at the mouth of the Minnesota River when the U.S. Army arrived in 1819 to build Fort Snelling.

Their Children

Records show that Margaret and Jacob's first child, John, was born around 1823 at Sandy Lake. Their second child, Nancy, was born soon after near Lake Superior. Another daughter, Sarah (Sally), was born at Gull Lake. They also had a daughter named Jane.

They had nine children in total, with African, Ojibwe, and Swedish backgrounds. Two of their children died young. Census records say Cecilia, James, and George were born near Lake Superior in 1835, 1837, and 1844. However, some historians wonder if this is accurate, given how far Margaret would have had to travel from where they lived.

Life Near Fort Snelling

In the 1830s, the Fahlstrom family lived on a small farm near Coldwater Spring. This was less than two miles from Fort Snelling. There were other cabins built there in the 1820s.

Jacob started working for the U.S. government around 1825. He worked as a blacksmith's helper, supplied wood, and carried mail. A map from 1837 shows "Jacob's" home next to a blacksmith's shop.

Slavery Near Fort Snelling

Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom and her brothers were "free Black" people. At the same time, there was a small community of enslaved people at Fort Snelling. Even though slavery was technically illegal in Minnesota, many enslaved African Americans lived and worked there.

The Fahlstroms might have lived near Rachel, an enslaved woman who lived at Fort Snelling from 1830 to 1831. She later successfully sued for her freedom. In 1835, Lawrence Taliaferro, an Indian agent, brought 14-year-old Harriet Robinson to work as a servant. Harriet married Dred Scott, an enslaved man, around 1837. They later became famous for their unsuccessful fight for freedom in the United States Supreme Court.

A historian named Lea VanderVelde noted that Harriet, after marrying Dred Scott, would not have been allowed to have visitors like Margaret Fahlstrom. Margaret also had no reason to go inside the fort.

Native Families at Camp Coldwater

Margaret was one of several Native women living at Camp Coldwater. Most of them had both Native and European backgrounds. Some, like Margaret, were married to blacksmiths or laborers. Others were wives of fur traders. Some women there were refugees from a settlement in Canada.

VanderVelde suggested that Margaret and other free Native women had a "poorer" standard of living compared to Harriet Robinson, who lived as a servant in a wealthy household. Agent Taliaferro himself felt sorry for Jacob Fahlstrom because he was poor and had a large family to support.

Relations with the Ojibwe

Margaret's brothers often visited her at Camp Coldwater. Her brother Stephen often worked as an Ojibwe interpreter for Agent Taliaferro. He might have lived with the Fahlstroms for a while. In 1837, Stephen Bonga signed the Treaty of St. Peters, which was an agreement between the U.S. government and several Ojibwe groups. This treaty gave land to the U.S. and promised money to "mixed-blood" relatives of the Ojibwe.

Keeping the Peace

In 1838, there was a fight between the Dakota and Ojibwe at Coldwater Spring. Agent Taliaferro tried to prevent more conflict. In 1839, he sent Stephen Bonga to tell Ojibwe Chief Hole-in-the-Day not to bring 500 members of his tribe to the St. Peter's Agency. The Chief wanted to complain about having to travel far for payments. Taliaferro wanted to avoid more fighting between the Ojibwe and Dakota.

Chief Hole-in-the-Day refused to turn back. He arrived on June 20 and held a meeting with Dakota leaders. Stephen Bonga was the interpreter. By June 23, 1839, many Ojibwe and Dakota people had gathered. They reportedly spent the day "dancing together, and in foot races." On June 30, Chief Hole-in-the-Day announced he was leaving. On July 1, the Ojibwe and Dakota smoked a peace pipe.

Moving from the Fort Area

After 1837, many new settlers came to the region. Officers at Fort Snelling worried about problems like drunkenness and trees being cut down. In 1837, Jacob Fahlstrom and other residents signed a petition to the President. They were concerned about losing their land rights.

In 1839, the U.S. government ordered all settlers to leave the Fort Snelling military reservation. In 1840, all civilians, including the Fahlstroms, were forced to leave Camp Coldwater. The Fahlstroms moved across the river, but found they were still on reservation land. They were evicted two more times. Finally, they settled in the St. Croix River valley, first in Lakeland, then in Afton.

Life as a Preacher's Wife

For the next 20 years, Jacob Fahlstrom became a famous Methodist missionary. He was called "Father Jacob" and was known as the most effective minister for Native Americans. Jacob's ability to speak Ojibwe and his family ties through Margaret were key to his success. Church writings show Margaret's involvement in Methodist gatherings. They also mention her welcoming traveling preachers into their home. Historians note her strong Christian faith.

Historian W.H.C. Folsom wrote about Margaret's intelligence: "At Lake Superior, in 1823, [Jacob] had been married to Margaret Burgo, a woman of fine mind. With her limited educational privileges, very few of any age or race can be found her equal. Mr. and Mrs. Folstrom were both consistent Christians, and members of the Methodist church for many years."

Becoming Methodists

In 1837, Margaret's brother Stephen Bonga worked as an interpreter for Reverend Alfred Brunson. Brunson started a Methodist mission for the Mdewakanton Dakota people.

In 1838, Brunson met Jacob Fahlstrom and soon converted him to Methodism. Even though Brunson's mission didn't convert many Dakota people, he thought converting the Fahlstrom family was his biggest success. He wrote that their conversion led to their family's education and usefulness in Minnesota.

Several Fahlstrom family members, including Margaret, are listed in a church record. Their oldest daughter, Nancy Fahlstrom, was remembered as a very smart woman. She served as an interpreter during church services for missionaries and the Dakota people.

Moving to Washington County

After being forced to leave Camp Coldwater, the Fahlstroms moved to Washington County. From 1840 to 1850, they lived in the area that became Lakeland. In 1850, they settled on a farm in Afton.

In 1840, Jacob became a licensed "exhorter" in the Methodist Church. He began missionary work as the first lay preacher for areas like Big Sandy Lake and Fond du Lac. He often traveled far from home, covering a large area. He also earned money by carrying mail. Stories about his travels and adventures made him well-known.

While living in Washington County, Margaret and her children often hosted traveling Methodist clergymen.

Each spring, Margaret and her children enjoyed visiting Manitou Island in White Bear Lake. They went there to make maple sugar. Making maple sugar was a long-standing tradition for Ojibwe women at White Bear Lake.

Later Years in Afton

Jacob Fahlstrom died in 1859. Margaret and her oldest daughter Nancy continued to live on the family farm. Margaret's youngest son, George, took over the farm.

Land Grants for Mixed-Blood People

On May 11, 1864, Margaret Folstrom and her daughter Nancy received "half-breed scrip." This was a land grant for 80 acres each from the U.S. government. It was for "mixed-bloods belonging to the Chippewa of Lake Superior," as promised by a treaty from 1854. In 1863, the government decided that mixed-blood people could get these land grants even if they hadn't lived with the Chippewa of Lake Superior at the time of the treaty.

Margaret's Death

Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom died on February 6, 1880. She was buried next to Jacob in the Fahlstrom Cemetery in Afton Township. In 1964, a memorial was placed on their graves by the Minnesota Methodist Historical Society. Her name is engraved as "Margaret Bungo Fahlstrom."

Why Margaret's Story Matters

Recently, people have wondered why Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom was not as well-known as Jacob Fahlstrom. Historian Mattie Harper DeCarlo says that without Margaret, Jacob might not have had the success that made him famous. DeCarlo believes Margaret's story was overlooked because of how history was often told, which sometimes left out the stories of women of African ancestry.

Identity in Fur Trade Society

In early Minnesota, "race" often meant the difference between "white" and "Indian." Many people had mixed backgrounds due to marriages between different groups. People's identities were often based on their culture and lifestyle, not just their skin color. This was a unique time for people of African descent like George Bonga, Margaret's brother.

Mattie Harper also suggests that George Bonga and his brothers were seen as "half breeds" in the fur trade. This meant they were like others of mixed ancestry. Jacob Fahlstrom's choice to marry Margaret Bonga showed the importance of her father Pierre Bonga and his Ojibwe family connections. Margaret also had useful skills for a fur trade family. She was likely seen as culturally "French" within the fur trade community.

Some early Minnesota historians simply called Margaret "a Chippewa." However, in 1888, one historian mentioned Margaret's grandfather, Jean Bonga, as one of the "negroes taken prisoner." He noted that Jean Bonga had many descendants in Minnesota, but didn't name Margaret.

Another historian in 1908 called Margaret "a half-blood Chippewa woman." But when talking about her brother, he called him "George Bonga, the mixed blood Indian and negro."

Women in the Methodist Church

Margaret Fahlstrom is part of a long history of women who supported the Methodist Church's missionary work. The founder of Methodism, John Wesley, encouraged women to play active roles. They led classes, shared their Christian experiences, and gave talks. Wesley even said women could be lay preachers if they had a special calling.

Swedish-American History

In 1879, historian Robert Grönberger wrote that Jacob Fahlstrom married a woman who was part Indian and part Black. Another historian, Eric Norelius, wrote in 1890 that Jacob's wife was part Chippewa and part Black, and that they spoke Chippewa at home.

However, in 1910, Algot E. Strand wrote that Jacob's children denied having any Black ancestry. Strand incorrectly claimed Margaret was the daughter of "Bungo," who he said was a chief.

In 1984, Emeroy Johnson questioned the accuracy of the early accounts. He thought it was unlikely a Black woman would be in northern Wisconsin and married to a Native American in the late 1700s.

More recently, in 2015, historian Elinor Barr wrote that Jacob Fahlstrom married "Margaret Bonga, daughter of an Ojibwa woman and Pierre Bonga, a Black man."

Renewed Interest in the Bonga Family

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the history of the Bonga family, including Margaret Bonga Fahlstrom.

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |