Harriet Robinson Scott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harriet Robinson Scott

|

|

|---|---|

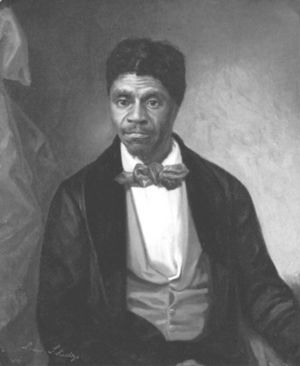

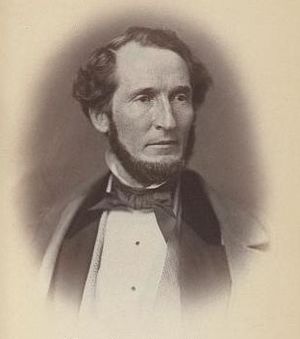

Scott in 1857

|

|

| Born | c. 1820 |

| Died | June 17, 1876 (aged c. 56) |

| Resting place | Greenwood Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Laundress |

| Known for | Dred Scott v. Sandford Harriet v. Irene Emerson |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Eliza Scott Lizzie Scott |

Harriet Robinson Scott (born around 1820 – died June 17, 1876) was an African American woman. She bravely fought for her freedom for eleven years. Her husband, Dred Scott, joined her in this long legal battle. Their fight ended with a famous decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857. This case was called Dred Scott v. Sandford.

On April 6, 1846, their lawyer, Francis B. Murdoch, started a case for Harriet. It was called Harriet v. Irene Emerson. This made the Scotts the only married couple to file separate freedom lawsuits at the same time.

Harriet was born into slavery in Virginia. She lived for a short time in Pennsylvania, which was a free state. Then, she was taken to the Northwest Territory. This area is now Minnesota. She was brought there by Lawrence Taliaferro, who owned slaves and worked as an Indian agent.

Around 1836 or 1837, Harriet married Dred. He was also enslaved and had been brought to Fort Snelling by Dr. John Emerson. Dr. Emerson was a military doctor. Their wedding was a civil ceremony led by Taliaferro. He was a justice of the peace. Taliaferro never actually sold Harriet to Dr. Emerson, because slavery was against the law in that territory.

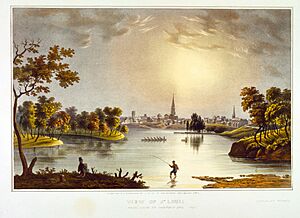

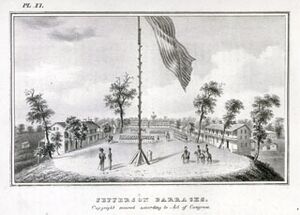

In 1838, Harriet gave birth to their first child. Her name was Eliza. She was born on a steamboat called Gipsey. The boat was traveling north on the Mississippi River. This was in free territory. In 1840, the Scott family moved to St. Louis in Missouri. Missouri was a slave state. They lived with Irene Emerson, Dr. Emerson's wife. She later hired them out to her brother-in-law, Captain Henry Bainbridge. This was at Jefferson Barracks.

After Dr. Emerson died in 1843, Dred went with Captain Bainbridge to Louisiana and Texas. Harriet and their two daughters stayed in St. Louis. Harriet was hired out to Adeline Russell. She was the wife of a grocery owner. Harriet most likely worked as a laundress.

In 1846, Dred Scott returned to St. Louis. He tried to buy his freedom from Mrs. Emerson, but she said no. The Scotts then decided to go to court to win their freedom. Harriet was a member of the Second African Baptist Church. She knew that many enslaved women in St. Louis had won their freedom lawsuits.

The Scotts had a strong case. It was based on earlier court decisions like Winny v. Whitesides (1824) and Rachel v. Walker (1836). They should have won easily. They lost their first trial in 1847 because of a small mistake. But they were given a new trial. While their cases were waiting, Mrs. Emerson ordered the sheriff to take them. The sheriff then hired them out.

Dred Scott won his second trial in 1850. This briefly made his family free. But Mrs. Emerson appealed the decision. Lawyers for both sides agreed to focus only on Dred's case. They thought the result would apply to Harriet's case too. Some historians believe this was a mistake. Harriet's claim to freedom was stronger than Dred's. Also, the legal status of children was decided by their mother's status. As their case went through different courts, it became clear that the courts would no longer follow past decisions.

On March 6, 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court made its ruling. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney led the court. The court said the Scotts were not American citizens because of their race. This meant they had no legal rights. The court also said that the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the Missouri Compromise were against the Constitution.

The Scotts did not win their freedom in court. But they were finally freed on May 26, 1857. Their high-profile loss was covered by news across the country. This caused embarrassment for Calvin C. Chaffee. He was a Congressman from Massachusetts and an abolitionist. He had married Irene Sanford Emerson.

The Supreme Court's ruling caused a big problem for the country. It made abolitionists even stronger. It also helped lead to the American Civil War. This war ended slavery. It also led to the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Dred Scott died in 1858. But Harriet lived through the Civil War. She spent her later years with her two daughters and grandchildren. Her grandchildren were born free.

The Harriet Scott Memorial Pavilion is at Greenwood Cemetery in Hillsdale, Missouri. It honors her memory. The Dred and Harriet Scott Statue is at the Old Courthouse in St. Louis. It marks where they began their fight for freedom.

Contents

Harriet's Early Life

Harriet Robinson was born into slavery around 1820. This happened in Virginia. After that, she lived briefly in Pennsylvania. We do not know much about her early life.

Her first known slaveholder was Major Lawrence Taliaferro. He was from Virginia. It was said that Taliaferro "inherited" Harriet. He did not buy her. The name Robinson might have come from the family who enslaved her mother. A Robinson family lived near where Lawrence Taliaferro grew up. This was in King George County, Virginia. But there is no record connecting them to Harriet.

Another idea is that Harriet was given to Taliaferro and his wife. Her name was Elizabeth Dillon. This might have been part of a wedding gift when they married in 1828. Elizabeth was known as Eliza. She was the daughter of Humphrey Dillon. He owned an inn in Bedford, Pennsylvania. Her father had registered three children as slaves in the 1820s. These included two daughters and one son. Their mother was an enslaved servant named Eliza Diggs.

Pennsylvania law freed all children of slaves born in the state. It also freed any enslaved person kept there for more than six months. But local custom allowed slaveholders to register children of enslaved mothers. They could be slaves until age 28.

While in Pennsylvania, Harriet likely learned to be a laundress or chambermaid. This was at the inn owned by the Dillon family. Her own mother might have taught her. Harriet never learned to read or write.

Moving to Minnesota Territory

In 1835, Lawrence Taliaferro moved his whole household. They joined him at St. Peter's Indian Agency. This was near Fort Snelling in what is now Minnesota. He had worked there since 1820. He was an Indian agent for the Dakota and Ojibwe tribes. President Andrew Jackson had reappointed him for another term.

Fourteen-year-old Harriet went along as a servant. She worked at the Taliaferros' agency house. Harriet likely made the six-week trip from Bedford, Pennsylvania. She traveled with Lawrence, his wife Eliza, and his brother-in-law Horatio Dillon. An 18-year-old servant named Eliza and a few enslaved men also came. They traveled from western Pennsylvania to St. Louis, Missouri. From there, they took the steamboat Warrior up the Upper Mississippi River. They went to St. Peter's Agency.

Slavery at Fort Snelling

Agent Taliaferro had brought black servants to Minnesota as slaves since 1825. Over the years, he became the biggest slaveholder in the area. He enslaved at least 21 black servants during his life. Taliaferro often hired them out to officers at Fort Snelling. He kept a few servants in the agency house. This house was about half a mile outside the fort walls.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had banned slavery north of the Ohio River. But slavery continued in the region for many years. Also, slave labor on U.S. military bases was often allowed. Sometimes it was even encouraged before the Civil War. At Fort Snelling, U.S. Army officers got money for servants. But they often used enslaved labor instead. They kept the extra money for themselves. In the 1820s and 1830s, about 15 to 30 enslaved people worked at Fort Snelling at any time.

Life at St. Peter's Agency

While living at the Indian agency house, Harriet Robinson and Eliza worked as maid servants. They helped Mrs. Taliaferro with her hair and clothes each day. They also did household chores. Each night, they slept in the basement kitchen. They slept on a pallet of rags in front of the open fire. At dawn, they started the fire to warm the house.

During winters, Harriet likely built and tended fires all day. The winters were so cold that laundry would "simply freeze stiff." This meant Harriet was free from laundry for most of the winter. During the rest of the year, the community saw clean clothes and bathing as a sign of their "superiority" over local Native American tribes.

At dinner, the servant women served food in the Taliaferros' dining room. They carried it from the basement, up stairs, outside, and into the main house through the back door. Mrs. Taliaferro received many compliments from guests. They liked her elegant table settings and how well she ran her household.

Important Guests

In a book called Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery's Frontier (2009), Lea VanderVelde suggests Harriet served dinner to several important visitors. This was at the St. Peter's Agency house between 1835 and 1836. These guests included fur trader Joseph Renville and painter George Catlin. British geologist George William Featherstonhaugh also visited. Explorer Joseph Nicollet stayed with the Taliaferros in the winter of 1836. He became very close to Mrs. Taliaferro.

Harriet probably opened the front door for Dakota and Ojibwe visitors. She likely knew many of them by name. Henry Hastings Sibley, a new manager for the American Fur Company, also visited often.

Marriage to Dred Scott

On May 8, 1836, Dred Scott arrived at Fort Snelling. He came by steamboat. He was one of at least five enslaved men who arrived that day. They came with 140 members of the 5th Infantry Regiment. At that time, he was known as "Etheldred." He was a personal servant to John Emerson. Dr. Emerson was a military surgeon. He had bought Dred as a slave in St. Louis, Missouri. Then he took him to Fort Armstrong in Illinois. Illinois was supposed to be a free state.

In the next few months, Dr. Emerson and Agent Taliaferro worked well together. In late June 1836, they vaccinated nearly 1,000 Dakota people against smallpox. Etheldred probably helped them. Emerson visited Taliaferro at the agency house for the first time on July 3.

Historian Lea VanderVelde thinks Harriet and Dred met before this. Maybe Harriet was working in the agency garden. Dred might have been on the prairie looking after Dr. Emerson's horse. They would also have seen each other at the sutler's store. This was inside the fort gate.

Their Wedding

Harriet Robinson and Dred Scott were married in a civil ceremony. Lawrence Taliaferro, as a justice of the peace, performed the wedding. This happened in 1836 or 1837. Harriet was about seventeen. Dred was about forty years old. This was Dred's second marriage.

The exact date of the wedding is not known. Taliaferro had no journal entries for 1837. He reportedly ran out of paper. Their marriage was the last one Taliaferro performed. He did many weddings as an Indian agent in Minnesota.

Civil wedding ceremonies were not common for enslaved couples then. As an Indian agent, Taliaferro believed in Western-style marriages. He thought they helped families on the "frontier." This included Native Americans, fur traders, soldiers, and other settlers.

Moving to Fort Snelling

After they married, Harriet left St. Peter's Agency. She went to live with Dred at Fort Snelling. Officers at the fort called her "Har.Etheldred" or "H.Dread" in their records.

By September 14, 1837, Harriet was already married to Dred. John Emerson now owned her. That day, Dr. Emerson hired Harriet out. She worked for Lieutenant James L. Thompson and his wife Catherine. Catherine later testified in the Scotts' trial. She was a witness to their time at Fort Snelling.

That fall, Harriet was the only servant woman left at Fort Snelling. Her housekeeping skills were in high demand. She was hired out to three officers. Then, in November, she was hired only by Major Joseph Plympton. He was the post commandant. Taliaferro had previously hired his servant Eliza to Plympton. Now Plympton paid Dr. Emerson for Harriet's work.

Dr. Emerson Leaves

Around this time, Dr. Emerson was given a new assignment to St. Louis. He had asked for this move. But he had to wait for his replacement to arrive. He could not leave until October 20, 1837. Freezing conditions on the Mississippi meant he had to travel by canoe. He left most of his belongings behind. Emerson left Harriet and Dred at Fort Snelling for the winter. He hired them out to other officers and collected their pay. After reaching St. Louis, Emerson was quickly moved again. This time he went to Fort Jesup in Louisiana.

Legal Questions

Harriet said in her 1846 lawsuit that Taliaferro "sold" her to Emerson. But there is no record of an actual sale. Legal historian Walter Ehrlich writes that Harriet and Dred agreed to be legally married. Taliaferro then informally gave his ownership of Harriet to Emerson. In his 1864 autobiography, Taliaferro wrote that he performed the "union of Dred Scott with Harriet Robinson – my servant girl which I gave him."

Taliaferro might have been unsure about Harriet's true status when he married her to Dred. Around the time his autobiography was published, Taliaferro gave a newspaper interview. He said he "married the two and gave the girl her freedom." Even if that was his plan, he did not write down her manumission. In reality, the Scotts remained enslaved by Emerson.

Rachel v. Walker (1836)

In June 1836, before Harriet and Dred married, an important freedom suit was decided. It was Rachel v. Walker. This case was in the Missouri Supreme Court. Rachel was an enslaved woman. Colonel J. B. W. Stockton had bought her in St. Louis. He took her to Fort Snelling, where she lived from 1830 to 1831. Stockton then took Rachel to Fort Crawford in Michigan. The Missouri Supreme Court agreed that Rachel should be free. They ruled that she became free when the army officer took her to live in free territory.

Eliza's Birth

In the fall of 1838, Harriet Scott gave birth to her first child. It was a baby girl named Eliza. She was born on a steamboat. The boat was heading north up the Mississippi River. It was going from St. Louis back to Fort Snelling. Eliza Scott was born north of Missouri. This meant she was born in free territory. This was according to the Missouri Compromise. The details of Eliza's birth came about because Dr. John Emerson kept changing his mind about where to live.

Called to Louisiana

On November 22, 1837, Dr. Emerson went to Fort Jesup in Louisiana. He immediately started complaining about the climate. He sent many requests for another assignment. He wanted to be closer to Illinois. He hoped to secure his land claims near Fort Armstrong there. In Louisiana, John Emerson met Eliza Irene Sanford. She was visiting from St. Louis. She was the sister-in-law of Captain Henry Bainbridge, also from St. Louis. On February 6, 1838, John and Irene married in Louisiana.

Soon after, Dr. Emerson sent for the Scotts. He wanted them to join him and his new wife in Louisiana, a slave state. Harriet and Dred left Fort Snelling in April 1838. They likely took the first steamboat after the spring thaw. Harriet was in the early stages of pregnancy.

We know little about Harriet and Dred's trip south. In the summer of 1838, Emerson wrote a letter. He said, "Even one of my negroes in St. Louis has sued me for his freedom." There is no record of a lawsuit at this time. But VanderVelde suggests that when they reached St. Louis, the Scotts might have had doubts. They may have not wanted to continue to Louisiana. They might have told Dr. Emerson this.

Journey Back to Fort Snelling

After months of complaining, Dr. Emerson got a transfer back to Fort Snelling. On September 26, 1838, Harriet and Dred Scott were on the steamboat Gipsey. Dr. and Mrs. Emerson were also on board. The boat left St. Louis.

Harriet was very pregnant by then. She was probably very uncomfortable. The Gipsey was a small, cramped steamer. It was "more of a tugboat than a pleasure ship." Small boats like the Gipsey were known for extreme heat. This came from their wood furnaces and steam engines. The sternwheeler had no private cabins. It had only two group cabins, one for ladies and one for gentlemen. Harriet may have gone below deck. She might have found "a secluded corner" to give birth. This could have been "behind the barrels of cargo and bales of blankets destined for the Indians."

In Dred Scott v. Sandford, Eliza Scott's birthplace was described. It was "on board the Steamboat Gipsy north of the north line of the State of Missouri & upon the River Mississippi." The place of her birth became very important in their freedom lawsuit. Dred and Harriet would call the ship's captain as a witness. Methodist missionary Reverend Alfred Brunson was also on the Gipsey. He later mentioned Eliza's birth in his autobiography.

The trip was very slow. This was because of low water levels on the Mississippi River. The Gipsey finally reached Fort Snelling on October 21, 1838.

Naming the Baby

Many people thought Eliza Scott was named after Eliza Irene Sanford Emerson. But Mrs. Emerson went by her middle name, Irene. Eliza was also the first name of Eliza Dillon Taliaferro. And it was the name of Harriet's friend and fellow servant, Eliza. Historian VanderVelde suggests Harriet named her daughter after her friend.

Life as a New Mother

Dr. Emerson stayed at Fort Snelling from October 1838 to May 1840. During this time, the Scott family likely lived in the basement of the fort hospital again. They settled back into life at the fort. Harriet and Dred continued to work for Dr. and Mrs. Emerson. They also worked for other officers. By the time they returned to Fort Snelling, many of Harriet's old friends had left. There were very few ladies and domestic servants at the fort during baby Eliza's first winter.

Life at the fort had also become harder. Officers struggled to keep military order. This was due to widespread drunkenness and many soldiers leaving without permission. In 1839, Emerson argued with Lieutenant McPhail. McPhail was the Fort Snelling quartermaster. He agreed to give the Emersons a stove. But he refused to give a second stove for the Scott family. Lieutenant McPhail punched Dr. Emerson in the nose and broke his glasses. Emerson then challenged McPhail to a duel. Emerson was briefly arrested but not punished. He seems to have won. Records show Emerson was charged for two stoves. VanderVelde notes that stoves were usually only for officers and married enlisted men. The fact that Dr. Emerson fought for a stove for the Scott family suggests he tried to protect and provide for them.

Moving to Missouri

On May 29, 1840, Harriet, Dred, and eighteen-month-old Eliza left Fort Snelling. They traveled by steamboat with John and Irene Emerson. Dr. Emerson left the Scott family in St. Louis, Missouri, with his wife Irene. He then went to Cedar Keys, Florida, alone. He stayed in Florida for two and a half years. He served as a medical officer in the Second Seminole War.

Many have wondered why Harriet and Dred moved to Missouri, a slave state. They could have tried to stay in Iowa Territory. There, they might have lived in freedom. Historian Lea VanderVelde argues that the Scotts had no other good choice. On May 6, 1840, the civilian settlement near Fort Snelling was burned down. A U.S. marshal forced almost everyone out. Unlike freedman Jim Thompson, who built houses for refugees, the Scotts lacked skills. They did not know hunting, fishing, or the Dakota language. These were important for surviving in Minnesota's harsh climate.

As long as Dr. Emerson was alive, the Scotts had some protection as a family. His long absences also gave Harriet and Dred some freedom in their lives. Even if they depended on him financially.

Life on the Sanford Farm

Irene Sanford Emerson went to live with her father, Colonel Alexander Sanford. He had a 380-acre farm in north St. Louis County, Missouri. Her brother, John F. A. Sanford, had bought the farm for their father. Colonel Sanford enslaved four farmhands. They lived in separate slave quarters. The Scott family likely stayed there.

At first, Harriet and Dred probably kept working as house servants for Mrs. Emerson. They did not have experience with heavy farm work. Later, they were "rented out" to friends and acquaintances of Mrs. Emerson and Colonel Sanford in St. Louis. Laundresses were in high demand there.

Hired Out in St. Louis

Dr. Emerson was discharged from the Army Medical Corps in 1842. This was after the Seminole War ended. He was disappointed. He returned to St. Louis. He bought a 19-acre plot of land outside the city. But he had little money. He tried to get back into the Army but failed.

Dr. Emerson did not have a steady income. He seemed to rely on money from "hiring out" Harriet and Dred. They worked for other families in St. Louis. Selling the Scotts in the St. Louis slave market was not an option. By then, potential buyers knew that enslaved people who had lived in the North could sue for freedom.

In the summer of 1843, Dr. Emerson settled in Davenport, Iowa. He had claimed land there before. He tried to start his own doctor's practice. Meanwhile, Harriet probably stayed in St. Louis. Dred had started working for Irene's brother-in-law, Captain Henry Bainbridge. This was at Jefferson Barracks in March 1843.

Dr. Emerson's Death

John Emerson died suddenly on December 29, 1843. He was forty years old. He quickly wrote a will before he died. He mentioned his wife and infant daughter Henrietta. But he said nothing about Dred or Harriet. An inventory of his property in Missouri also did not mention slaves. Mrs. Emerson was now a thirty-year-old widow. She was shocked by his death. She moved back in with her father. She had a baby daughter who lost her father. She also had a new house being built in Iowa that she no longer needed. The Scott family's future was likely not on Irene Emerson's mind right after her husband died.

Lizzie's Birth

In 1844, Harriet gave birth to her second daughter, Lizzie. This happened at Jefferson Barracks in Missouri. Lizzie was born in a slave state. But by law, children inherited their mother's status. So, if Harriet won her freedom, Lizzie would also be free. Harriet likely named this baby after another Taliaferro servant named Lizzie. Besides Eliza and Lizzie, Harriet had two sons who died as infants.

Dred Leaves with the Army

On April 27, 1844, Dred Scott left with Captain Henry Bainbridge. The whole Third Infantry Regiment went on a steamship to Louisiana. They joined the "Army of Observation" led by General Zachary Taylor. Dred worked as Bainbridge's personal valet. He went with him as far as Corpus Christi, Texas in March 1845. Bainbridge finally sent Dred home to St. Louis in March 1846. This was when troops were called up for the Mexican–American War.

Dred was away for two years. During this time, Harriet might have been hired out to Samuel Russell. He was a rich grocery merchant in St. Louis. Mrs. Russell later said that Colonel Sanford brought both Harriet and Dred to her home in a wagon. VanderVelde suggests Harriet most likely worked as a laundress for the Russells. She and her daughters were probably living at the Russell family home when Dred returned.

Second African Baptist Church

Harriet became a member of the Second African Baptist Church in St. Louis. Reverend John R. Anderson led this church. Anderson may have connected the Scotts to their first lawyer, Francis B. Murdoch. Murdoch started their freedom lawsuits. Murdoch had been a prosecutor in Alton, Illinois. There, an abolitionist newspaper editor, Elijah Parish Lovejoy, was killed by a mob in 1837. Anderson had been Lovejoy's typesetter. He moved back to St. Louis soon after the incident. Both men spent much time helping enslaved people in St. Louis sue for freedom.

The Freedom Lawsuits

Harriet and Dred were reunited in St. Louis in March 1846. He had returned from Texas. Since Dr. Emerson's death in December 1843, they were worried about their family's future. They were especially afraid of losing Eliza and Lizzie. Eliza was eight years old. This was an age when slave owners often separated children from their families. They would either hire them out or sell them. The Scotts also feared being sold as slaves in the plantation South.

At the same time, Harriet knew about many freedom suits. Enslaved women in Missouri had won these cases. She knew this through her church. She also likely knew from the community of black washerwomen in St. Louis. Many of them had successfully sued for freedom. Since Winny v. Whitesides in 1824, a legal rule had been set. It said that enslaved people taken to live in a free state or territory could not be re-enslaved. This was true even if they returned to Missouri. From 1824 to 1844, the Missouri Supreme Court often ruled for slaves suing for freedom. This time became known as the "golden age" of freedom suits in Missouri.

On April 6, 1846, Harriet and Dred Scott each filed separate lawsuits for freedom. Based on Missouri law, they had strong cases. They should have won easily. They could not have known they would start an eleven-year struggle. This fight would take their case from the circuit court of St. Louis County all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Mrs. Emerson Refuses

In March 1846, Dred Scott returned to St. Louis. Soon after, he asked Irene Emerson if he could buy his freedom. But she refused. Dred was in his fifties. He was probably sick with tuberculosis. He was no longer seen as a valuable asset. So, Mrs. Emerson's refusal was likely not because she wanted to keep Dred. He was nearing retirement age and would soon cost more than he earned.

Instead, her refusal probably came down to Harriet, Eliza, and Lizzie. They were worth much more as "human property." This was true for wages from "hiring out" and their potential selling price. Harriet was younger and healthier than Dred. Mrs. Emerson and her father, Colonel Sanford, had been collecting Harriet's monthly earnings for some time.

Even if Mrs. Emerson thought about freeing the Scotts, she might have realized something. Missouri law at the time tried to stop slave owners from "abandoning" their old, sick, and young slaves. It forced them to sell other property to support freed slaves. In the end, Colonel Sanford might have made the final decision. He was Irene's proslavery father. Alexander Sanford was a leader in the Anti-Abolitionist Society in St. Louis. As a woman, Mrs. Emerson could not give Dred the legal papers he needed to prove his freedom. She would need two white men to swear oaths confirming her signature.

Separate Lawsuits

Harriet and Dred filed separate requests in the St. Louis Circuit Court. This was on April 6, 1846. They quickly got permission to sue Irene Emerson. They did this later that day. By doing so, they became the first married couple to file freedom lawsuits together. One of their great-great-granddaughters, Lynne Jackson, later said Harriet filed a separate suit. This was "because, as a woman and as the mother, if for any reason Dred did not win his case but she did, then their daughters would be free." They did not file separate lawsuits for Eliza and Lizzie. Legally, the mother's status decided the children's status.

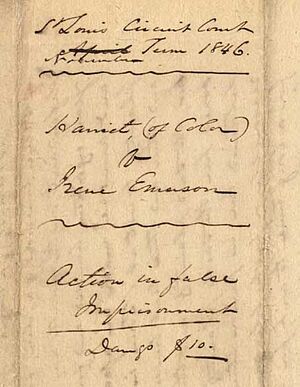

Harriet v. Irene Emerson (1847)

Harriet's case was filed as "Harriet of color vs. Irene Emerson." Her married name "Scott" was not used. This was because Missouri slave law did not allow enslaved people to enter legal contracts, including marriages. However, Dred's case was called "Dred Scott, slave vs. Irene Emerson." Harriet's case did not call her enslaved. This suggests her legal status was different from her husband's.

In Harriet's case, there was no proof that Lawrence Taliaferro sold her to John Emerson. Even if there had been a sale, it would not have been valid in Wisconsin Territory, a free territory. Also, Harriet had lived in the Taliaferro household in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania was a supposedly free state. Under Pennsylvania's laws, Harriet could have claimed her freedom when she turned 28.

Harriet's claim to freedom was likely stronger than Dred's. But it was also more complex and harder to prove. In the end, the Scotts' lawyer decided to use Missouri law for both Harriet and Dred. This was because the rule of "once free, always free" had often been upheld by the courts.

The Scotts' first lawyer, Francis B. Murdoch, filed many freedom suits. He filed one-third of all St. Louis freedom suits from 1840 to 1847. He always represented the enslaved people. Murdoch knew Pennsylvania law well. He had studied law in Bedford, Pennsylvania. He probably even knew Harriet's owner, Lawrence Taliaferro. Legal historian Lea VanderVelde argues that Murdoch understood the differences in Harriet and Dred's claims. Their later lawyers would not have this understanding.

Sadly for the Scotts, Murdoch suddenly left St. Louis. His mortgage was taken away. By spring 1847, he was off the case. In the months and years that followed, the Scotts had many different lawyers. But none were as dedicated to freedom suits as F. B. Murdoch.

Verdict for the Defendant

Dred's case did not go to trial until June 30, 1847. This was because of a busy court schedule. The jury decided in favor of Irene Emerson. This was due to a technicality. During questioning, witness Samuel Russell admitted something. He had not arranged to hire Harriet and Dred from Irene Emerson himself. His wife, Adeline, had handled it. He had simply paid for their work. Because of this, Russell's testimony was not allowed. The jury found that the Scotts had not proven Irene Emerson enslaved them. The Scotts' third attorney, Samuel M. Bay, asked for a new trial. He was granted one.

Harriet's Case Added Later

In December 1847, Judge Alexander Hamilton was checking the St. Louis Circuit Court records. He noticed he had forgotten Harriet's case. Only Dred's case had been formally given to jurors in June. The judge wrote that he meant to try Harriet's case at the same time. According to VanderVelde: "For correction, he simply recopied the entries of Dred’s case in Harriet’s name, down to the names of the jurors, as if her case had been placed before them six months before. From the judge’s viewpoint, overlooking Harriet was a harmless error as long as he granted her a new trial too. It seems that Harriet had been denied even this initial day in court – probably denied even this moment of the jury’s attention. As Dred’s wife, she was treated as just an appendage to her husband, much as history would treat her, swept along for the ride."

Irene Emerson v. Harriet (1848)

On December 4, 1847, Mrs. Emerson's lawyer, George Goode, objected to a new trial. He filed an appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court. Irene Emerson v. Harriet was considered on April 3, 1848. The Scotts' new lawyers, Alexander P. Field and David N. Hall, argued that Goode made a mistake. He brought the case to the state supreme court incorrectly. On June 30, 1848, the Missouri Supreme Court decided to dismiss Emerson's appeal. Judge William Scott ruled for Harriet. He noted that her husband's case was "in all respects similar...a similar disposition is made of it." It took two more years for the Scotts' cases to be heard again.

Taken by the Sheriff

On March 17, 1848, Judge Hamilton made an order. This was after a request from Irene Emerson's lawyer. The sheriff of St. Louis County was to take Harriet and Dred. He was to hire them out while the lawsuit continued. People in freedom suits were often jailed and hired out this way. Anyone hiring them had to promise the Scotts would not be taken out of the court's area. The money they earned would be held by the sheriff. It would later be paid to the side that won the lawsuit.

Mrs. Emerson's request was strange. Her lawyer had argued that the Scotts had not proven she owned them. She may have acted due to money problems. Her father, Colonel Alexander Sanford, died in February 1848. This arrangement allowed Mrs. Emerson to keep ownership. She could collect the Scotts' wages later. But she would not be responsible for them during that time.

For the next nine years, Harriet and Dred stayed with the sheriff. Or they were hired out by him. This lasted until March 18, 1857. We do not know where they were from 1848 to 1849. The Scotts likely spent some time in jail. Eliza and Lizzie were with them for part of the time. Dred was hired out to one of his lawyers, David N. Hall. This was for two years, from 1849 to 1851. Hall then died suddenly. Historian VanderVelde suggests that during a cholera outbreak, Dred and Harriet also worked for two St. Louis doctors. They were Dr. S. F. Watts and Dr. R. M Jennings. Both were called as witnesses when the court case finally happened in 1850.

From 1851 on, Harriet and Dred were hired out to another lawyer. His name was Charles Edmund LaBeaume. He was the brother-in-law of Peter Ethelrod Blow. Dred had worked for the Blow family as a servant for many years. They sold him to Dr. John Emerson when they had money problems. Many years later, at least seven members of the Blow family helped the Scotts. They supported them as they fought for freedom in court.

Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson (1850)

The Scotts' case finally went to court again. This was at the St. Louis County circuit court. It happened on January 12, 1850. The new trial was delayed for many reasons. These included the St. Louis fire of 1849 and a cholera epidemic after the fire. Judge Hamilton was in charge again. The Scotts were now represented by Alexander Pope Field and David N. Hall. Field was a well-known lawyer. Hall was a young lawyer who also worked on freedom suits.

The second trial was similar to the first. But this time, Field and Hall read Adeline Russell's testimony. She had said in a statement that she hired the Scotts from Irene Emerson. This proved Mrs. Emerson was their owner. Her husband, Samuel Russell, then testified in person again. He said he and his wife hired the Scotts and he paid their wages. The defense lawyers could no longer deny that Mrs. Emerson owned the Scotts. Instead, they argued she had the right to hire out Dred Scott. This was because Dr. Emerson was under military rule when he took Dred to Fort Armstrong and Fort Snelling. In doing so, they ignored the rule set by Rachel v. Walker in 1836. That case said military officers lost their slaves if they took them to a place where slavery was banned. Also, Scott's lawyers pointed out that Dr. Emerson chose to leave the Scotts at Fort Snelling. They worked for others when he first left for Fort Jesup.

Verdict for the Plaintiff

The jury quickly made their decision. They found Mrs. Emerson guilty of holding Dred Scott as a slave against his will in Missouri. Judge Hamilton then ordered that "the plaintiff recover his freedom against said defendant and all persons claiming under her by title derived since the commencement of this suit." Dred was found to have been free since 1833. This was when he went to Fort Armstrong. Harriet, Eliza, and Lizzie were also declared free. Their new freedom did not last long. Mrs. Emerson's lawyers appealed.

Combining the Cases

Irene Emerson's lawyers, Hugh A. Garland and Lyman D. Norris, first asked for a new trial. But they were denied. They then filed an appeal with the Missouri Supreme Court.

At this time, lawyers for both sides agreed. The result of Dred's case would apply to Harriet's too. They saw their cases as "identical." But they were not. Harriet had lived in Pennsylvania. She had not been "sold" to Dr. Emerson. However, proving she did not belong to anyone was hard for presumed slaves like Harriet. Since they had just won in the lower court, the Scotts' lawyer, David N. Hall, might have felt sure they could win again. This would be based on the Rachael v. Walker rule. He might not have gone into details about their different situations. By putting Harriet's case under Dred's, their daughters' legal status was now tied to Scott v. Emerson.

Scott v. Emerson (1852)

Lawyers filed papers in March 1850. But the Missouri Supreme Court delayed the case until October that year. David N. Hall wrote the paper for Dred Scott. But he died in March 1851. This left Alexander P. Field to continue alone as lawyer. Before Judge William Barclay Napton could finish writing the court's opinion, the Missouri judges faced their first supreme court election in August 1851. The case then had to be heard again by the newly elected court.

Decision for the Defendant

On March 22, 1852, Judge Scott announced the decision. The Missouri Supreme Court reversed the lower court's decision. This made Dred Scott enslaved again. In doing so, the court also reversed its own rule of "once free, always free."

Trying to Get Slaves Back

On March 23, 1852, the state supreme court decision was announced. The next day, lawyers for Irene Emerson Chaffee filed a notice. They asked the St. Louis County circuit court for the bonds signed by the Blow family. These covered the Scotts' court costs. They also asked for the wages Harriet and Dred earned since 1848. This included "six percent interest, allowed by law." And they asked for custody of the re-enslaved Scott family.

It was unclear what Mrs. Chaffee planned to do with the Scotts. By this time, Mrs. Chaffee had remarried. She moved to Massachusetts, a free state. She likely did not plan to move them there. Her brother, John F. A. Sanford, lived in New York, a free state. He often returned to St. Louis. But he probably had no use for slaves. He had already sold their late fathers' slaves. Historian Kenneth C. Kaufman suggests Mrs. Chaffee planned to sell Dred and his family. To protect them, Harriet and Dred sent their daughters into hiding. On June 29, 1852, Judge Hamilton denied the request. He would not transfer the Scotts and their earnings to Mrs. Chaffee.

Federal Court Case

The Missouri Supreme Court ruling affected the Scott family. It also affected the wider black community in St. Louis. Others who wanted freedom through Missouri courts now found that path closed. But Harriet and Dred did not give up. The only legal way left was to sue in federal courts.

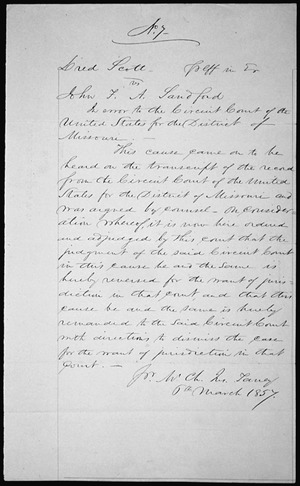

Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sanford (1854)

On November 2, 1853, a lawsuit was filed for Dred Scott. It was in the United States circuit court for the district of Missouri. Their new lawyer was Roswell M. Field. He was from Vermont and practiced real estate law. Field was a friend of Judge Hamilton and Justice Gamble. Lawyer C. Edmund LeBeaume had approached him. LeBeaume had hired Harriet and Dred from the sheriff. He had supported them since 1851. Roswell Field was said to have "strong antislavery sentiments." But his main interest was to fix the wrong use of Missouri law. This happened after the Missouri Supreme Court ignored past decisions. Many historians say the Scott family's freedom was less important to Field.

A more direct way would have been to appeal Scott v. Emerson directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. But doing so would likely fail. It would probably be dismissed. Just two years before, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear Strader v. Graham. In that case, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney said it was up to Kentucky, a slave state, to decide the status of a slave returning from Ohio, a free state. The laws of Ohio could not change this. So, the Supreme Court would not decide.

This time, Field chose to sue John F. A. Sanford. He was the brother of Irene Emerson Chaffee. He was also an executor of Dr. Emerson's estate. Sanford lived in New York. This allowed the suit to be brought to federal court. But he often returned to St. Louis for business. He was served with legal papers in St. Louis. This was likely when he visited his mentor, Pierre Chouteau Jr.. Irene Chaffee later said the Chouteau family convinced her brother to fight the Scott case to the end. Pierre Chouteau Jr. was the richest man in St. Louis. He was probably the largest slaveholder there. Over the years, the Chouteau family had many freedom suits against them. They fought hard to keep their slaves.

For the first time, the initial filing named Harriet as "Harriet Scott, then and still the wife of the plaintiff." Both children were named in the federal action as "Eliza Scott" and "Lizzy Scott." Biographer Kaufman writes, "If Roswell Field, as attorney for the Scotts, did nothing else for Dred and Harriet Scott, he restored to them at least in the court records the dignity of a family name, recognizing their lawful marriage and the two children born of that marriage." Another difference was that the federal filing asked for $9,000 in damages for Dred and Harriet. This was much more than the $10 asked for before.

In April 1854, John F. A. Sanford and his lawyer Hugh A. Garland filed a request to stop the case. They said the court had no right to hear it. They argued that Dred Scott did not have the right to be a citizen in Missouri. Their reason was "he is a negro of African descent – his ancestors were of pure African blood and were brought into this country and sold as negro slaves." This was the first time in the Dred Scott case that a black person's right to be a U.S. citizen was questioned.

Judge Wells agreed with Field's objection to this argument. He said a free black man would be "enough of a citizen" under the rule for different states. Sanford then pleaded not guilty. Field submitted an "Agreed Statement of Facts." It outlined Dred's travels with Dr. John Emerson. This statement had some mistakes. It later confused many historians. But it served its purpose at the time.

Verdict for the Defendant

On May 15, 1854, the case finally went to trial in federal court. Judge Robert W. Wells was in charge. Judge Wells told the jury that the laws in this case did not give Dred Scott his freedom. He explained that taking a slave to free Illinois only stopped his enslavement for a short time. This lasted until he returned to Missouri. This was the reason given by the Missouri Supreme Court in Scott v. Emerson in 1852. Judge Wells said, "The U.S. courts follow the State courts in regards to the interpretation of their own law."

Based on this, the jury decided for John Sanford. They found him not guilty of assault, trespass, and false imprisonment. They said Dred Scott, Harriet Scott, and their daughters were "negro slaves the lawful property of the defendant." Historian VanderVelde writes: "The Scotts had lost before, but their spirits must have sunk again to hear the foreman declare that the jury had sided against them. Given the verdict, Harriet and Dred probably sought, at this time, to change the girls’ hiding place before someone moved in to seize them." Field's request for a new trial was denied. He then filed an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

On May 30, 1854, President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas–Nebraska Act into law. This Act ended the Missouri Compromise. It allowed states to decide for themselves if they would allow slavery.

Montgomery Blair, a former St. Louis judge, moved to Washington, D.C.. Roswell Field asked him to represent the Scotts. On December 30, 1854, Blair finally wrote to Field. He agreed to take the case for free. This was after Gamaliel Bailey, editor of an antislavery newspaper, agreed to cover expenses. Blair likely never met the Scotts in person.

Meanwhile, Sanford's lawyer Hugh A. Garland had died. In his place, Reverdy Johnson and Missouri Senator Henry S. Geyer agreed to represent John F. A. Sanford.

From February 11 to 14, 1856, the Supreme Court heard the first arguments. Blair argued that an enslaved person freed in a free state stayed free. This was true even after returning to a slave state. He also argued that a free black person could sue as a citizen in federal courts.

Geyer and Johnson argued that Dred Scott was never free. They said Congress could not ban slavery in territories. Only individual states could decide that. This was the first time the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise was part of the Dred Scott case. They agreed Dred might have been free in Illinois. But they said he gave up his freedom when he returned to Missouri willingly.

After many discussions, the Supreme Court announced something on May 12, 1856. They ordered the lawyers to argue the case again next term. That summer, tensions between abolitionists and proslavery groups became violent. In the election on November 4, 1856, James Buchanan was elected president.

Illnesses

That year, Harriet had to care for Dred. He became very sick with tuberculosis. At one point, people thought Dred would die. His death would have stopped the Supreme Court case. But by fall 1856, Dred had recovered enough. He went back to sweeping Roswell Field's offices.

In December 1856, John F. A. Sanford had a nervous breakdown. He was moved to a mental hospital. He stayed there until he died the next year. Pierre Chouteau Jr. thought Sanford was stressed from money problems.

Presidential Inauguration

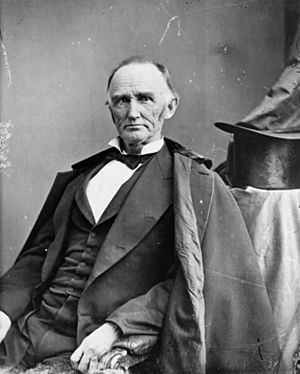

Lawyers for both sides filed printed papers. The second round of arguments happened from December 15 to 18, 1856. The Dred Scott case now got attention from news across the country and in Congress. On February 3, President-elect James Buchanan wrote to Justice John Catron. He asked if the Supreme Court could announce its decision before his inauguration in March. Catron later replied. He encouraged Buchanan to contact Justice Robert Cooper Grier. Grier was from the North. Buchanan hoped to influence Grier's decision on the Missouri Compromise.

The Supreme Court justices met many times in February and March. In his speech on March 4, 1857, President James Buchanan spoke about Dred Scott v. Sandford: "A difference of opinion has arisen in regard to the point of time when the people of a Territory shall decide this question for themselves. This is, happily, a matter of but little practical importance. Besides, it is a judicial question, which legitimately belongs to the Supreme Court of the United States, before whom it is now pending, and will, it is understood, be speedily and finally settled. To their decision, in common with all good citizens, I shall cheerfully submit, whatever this may be."

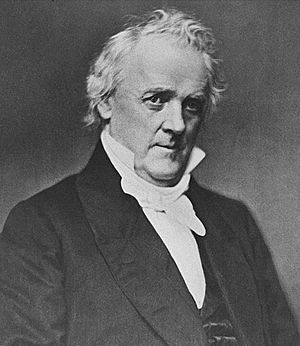

Supreme Court Decision

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney finally read the court's decision. The majority opinion stopped the Scotts from suing for freedom in several ways. The most debated ruling was that people of African descent could not be U.S. citizens. This was because of their race. Because of this, the Scotts and all African Americans could no longer sue in federal courts. Also, the Supreme Court did something new. It said two acts of Congress were against the Constitution. These were the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

At the end of his opinion, Justice Taney ruled that the U.S. Circuit Court in St. Louis should close the case. This was due to a lack of authority. However, the Supreme Court never actually sent the order. This was because the court costs for John F. A. Sanford were never paid. To this day, the federal court records have not changed. Still, on March 18, 1857, the state circuit court in St. Louis County closed their case. This was where the Scott family's legal battles began in 1846. Eleven years later, Harriet, Dred, Eliza, and Lizzie Scott were still enslaved.

Life After the Legal Battle

After their big loss in the U.S. Supreme Court, the Scott family became famous. In St. Louis, Dred Scott became a local celebrity. One newspaper called him "the best known colored person in the world." Dred gave interviews. He laughed about all the "fuss" made about him. But he was tired from the case. He said he would not do it all again. He was offered $1,000 to travel North and tell his story. He said no. Harriet reportedly did not like these offers. She was afraid he would be kidnapped.

Harriet was very careful about all the publicity. In spring 1857, many newspapers said Eliza and Lizzie were still in hiding. One article in the Missouri Republican said Mrs. Chaffee sent a "policeman" to "hunt them down."

Congressman Chaffee

Meanwhile, the national attention on the Dred Scott case was very embarrassing. This was for Republican Congressman Calvin C. Chaffee. He was a strong abolitionist from Massachusetts. He had married Irene Sanford Emerson in 1850. This was before he was elected to office in 1854. Newspapers across the country asked, "Who owned Dred Scott?" Mrs. Chaffee was shown to be the owner. Her husband was heavily criticized for being a hypocrite. Chaffee first said that only John Sanford had power in the lawsuit. He claimed that "neither myself nor any member of my family were consulted in relation to, or even knew of the existence of the suit till after it was noticed for trial, when we learned it in an accidental way.”

That claim was questioned again on May 5, 1857. John F. A. Sanford died in the mental hospital where he had been since December. Chaffee then quickly moved to transfer ownership of the Scotts. He wanted to give them to someone who could free them. Only a Missouri resident could free them, since they lived in Missouri. Taylor Blow stepped in to help. Congressman Chaffee said he would not profit from the Dred Scott case. But Irene Chaffee insisted on collecting the wages Harriet and Dred earned during the legal battle. These funds were reportedly $1,000. Mrs. Chaffee's lawyer collected them. They seem to have been given to her by the Chouteau family.

Free at Last

On May 26, 1857, the Scotts were officially freed. Harriet and Dred Scott appeared in the St. Louis Circuit Court. Taylor Blow was with them. The court records state: "Taylor Blow, who is personally Known to the Court, and acknowledges the execution by him of a Deed of Emancipation to his slaves, Dred Scott, aged about forty eight years, of full negro blood and color, and Harriet Scott wife of said Dred, aged thirty nine years, also of full negro blood and color, and Eliza Scott a daughter of said Dred and Harriet, aged nineteen years of full negro color, and Lizzy Scott, also a daughter of said Dred and Harriet, aged ten years likewise of full negro blood and color." Once their freedom papers were secured, Eliza, age 19, and Lizzie, age 14, finally came out of hiding. They looked much younger than their age. This might have been from not getting enough food.

Harriet took in laundry to earn money. Eliza and Lizzie helped her with ironing. Dred was offered a job as a doorman at Barnum's Hotel in St. Louis. It was one of the "widely known hotels in the West." Theron Barnum, a cousin of P. T. Barnum, ran the hotel. Dred was too old to carry heavy bags himself. He served as a celebrity greeter to hotel guests. Many were curious about his story. Dred accepted tips. He also delivered clean laundry that Harriet had washed.

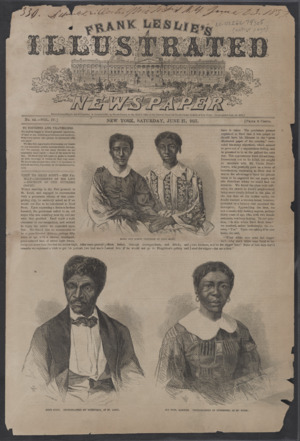

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

One day in June 1857, two journalists visited the Scott family. This was at their house in an alley off Carr Street. Harriet greeted them at the door. She was very protective of Dred. She was also suspicious of their reasons. Harriet first asked them to leave her family alone. But the journalists showed a letter from the Scotts' lawyer. Harriet recognized the signature. The reporters finally convinced Harriet to let her family pose for portraits. This was at photographer Fitzgibbon's studio the next day. Harriet agreed. But she said the family must also get their own copies of their daguerreotype portraits. The engraved portraits of Eliza and Lizzie Scott sitting together were famous. The individual portraits of Dred and Harriet were also famous. They were on the front page of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper on June 27, 1857.

Dred's Death

Dred Scott died at home on September 17, 1858. This was fifteen months after his family was freed. He died of tuberculosis. The New York Times published a long obituary. It said that "Few men who have achieved greatness have won it so effectually as this black champion." Dred's fame grew after his death. But his grave in St. Louis remained unmarked. He was first buried at Wesleyan Cemetery in St. Louis. He was later reburied at Cavalry Cemetery.

Grandchildren

Harriet Scott lived for almost 20 more years in freedom in St. Louis. She saw the Civil War and the end of slavery in the U.S. She was listed in St. Louis directories from 1859 to 1876. One entry listed her as "Scott, Harriet, widow of Dred, (colored), alley near Carr between 6th and 7th."

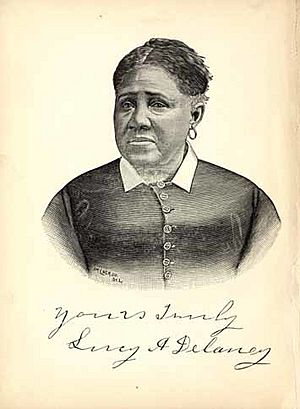

Over the years, she continued to work as a washerwoman. One of her daughters married Wilson Madison of St. Louis. The other remained unmarried. Harriet had two grandchildren who lived to be adults: Harry Madison and John Alexander Madison. On June 17, 1876, Harriet Scott died at her daughter and son-in-law's home. Three days later, she was buried at Greenwood Cemetery in St. Louis County. Her grave was also unmarked.

Historians have been confused about which daughter was the mother of her grandsons. Recently, genealogist Ruth Ann Hager explained. She said that "Eliza Scott Madison and her husband died at a young age, leaving their two teenage sons to be raised by her sister Lizzie." Based on family stories and public records, Hager argues that Lizzie later used a different name, Lizzie Marshall. She lived to be 99 years old. Relatives knew her as "Aunt Lizzie." She helped Scott family descendants with childcare and housework, even into her eighties.

Harriet's Legacy

The Dred Scott Heritage Foundation was started in June 2006. Its first project was to plan the 150th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision. The foundation has worked to make sure Harriet Scott's legacy is remembered alongside Dred's.

Harriet Scott Memorial Pavilion

The Harriet Scott Memorial Pavilion is in the Greenwood Cemetery. It is dedicated to her memory. The location of her unmarked grave was forgotten for many years. Etta Daniels found it in 2006. She was from the Greenwood Cemetery Preservation Association. In 2009, a headstone was finally placed to honor Harriet Scott. The pavilion was dedicated in 2010. There are no plans to move Harriet and Dred to the same cemetery. This is according to Lynne Jackson, their great-great granddaughter and president of the foundation.

Greenwood Cemetery was founded in 1874. It was the first burial ground for African Americans in St. Louis County, Missouri. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. About 50,000 people are buried there. But there are only 6,000 headstones. The pavilion allows people to buy memorial pavers. These honor people whose graves may never be found.

Old Courthouse

A painting of Harriet and Dred Scott hangs in the Old Courthouse in St. Louis. Also, in 2012, a bronze statue of Dred and Harriet Scott was dedicated. It is on the south lawn of the Old Courthouse. The Dred Scott Heritage Foundation ordered the statue. It shows them standing close, holding hands, with their heads held high. The statue marks where the Scotts' long legal battle began. It represents "a fight for liberty and dignity, through grace and perseverance."