Elijah Parish Lovejoy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elijah Parish Lovejoy

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 9, 1802 Albion, Maine, U.S.

|

| Died | November 7, 1837 (aged 34) Alton, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Resting place | Alton Cemetery |

| Education | Waterville College |

| Spouse(s) |

Celia Ann French

(m. 1835) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Owen Lovejoy (brother) Nathan A. Farwell (cousin) |

| Signature | |

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (born November 9, 1802 – died November 7, 1837) was an American Presbyterian minister, journalist, and newspaper editor. He was also a strong supporter of ending slavery. After he was killed by a group of people, he became a hero for the cause of ending slavery. He is also remembered as a champion of free speech and freedom of the press.

Lovejoy grew up in New England and went to what is now Colby College. He wasn't happy as a teacher, so he became a journalist and moved west. In 1827, he arrived in St. Louis, Missouri. Missouri was a slave state because of the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Lovejoy edited a newspaper there.

He later went back east to study to become a minister at Princeton University. When he returned to St. Louis, he started the St. Louis Observer newspaper. In this paper, he wrote more and more against slavery and the powerful people who supported it. Because of threats and attacks, Lovejoy decided to move his newspaper across the river to Alton in Illinois, which was a free state. However, Alton was also connected to the Mississippi River economy. People from Missouri who disliked Lovejoy could easily reach Alton. The town was also divided between those who supported slavery and those who wanted to end it.

In Alton, Lovejoy was shot and killed during an attack by a mob that supported slavery. The mob wanted to destroy a warehouse that held Lovejoy's printing press and materials against slavery. After his death, many people across the country were shocked and angry. His murder inspired John Brown, another famous abolitionist, to dedicate his life to ending slavery. Lovejoy is often seen as a hero for the cause of ending slavery and for a free press. A monument was built in Alton in 1897 to honor him.

Contents

Elijah Lovejoy's Early Life and Education

Elijah Parish Lovejoy was born on November 9, 1802, in a farmhouse near Albion, Maine. At that time, Maine was part of Massachusetts. He was the oldest of nine children. His father was a Congregational preacher and farmer. His mother was a homemaker and a very religious Christian. Elijah's father wanted his sons to get a good education, and Elijah learned to read the Bible early from his mother.

After attending public schools, Lovejoy went to private academies. He learned Latin and mathematics. In 1823, he started at Waterville College (now Colby College). He received help to pay for his studies. From 1824 until he graduated in 1826, he also led the Latin School, a high school connected to Colby. In September 1826, Lovejoy graduated with honors and was the top student in his class.

Moving Westward

After college, Lovejoy taught at an academy in Maine. But he wasn't happy teaching. He thought about moving to the South or west to the Northwest Territory. His old teachers told him he could best serve God in the West, which is now called the American Midwest.

In May 1827, he went to Boston to earn money for his trip. He wanted to go to Illinois, a free state. He couldn't find work in Boston, so he started walking towards Illinois. He stopped in New York City and eventually found a job selling newspaper subscriptions. After struggling with money, his old college president sent him the funds he needed. Before he left for the West, Lovejoy wrote a poem that seemed to predict his death:

| I go to tread |

| The Western vales, whose gloomy cypress tree |

| Shall haply, soon be enwreathed upon my bier; |

| Land of my birth! My natal soil, Farewell |

| —Elijah P. Lovejoy |

Lovejoy's Career in Missouri

In 1827, Lovejoy arrived in St. Louis, Missouri. St. Louis was a big port city in a slave state. However, it was also seen as the "gateway to the West." It shared a long border with Illinois, which was a free state.

Lovejoy first ran a private school in St. Louis with a friend. But he became more interested in journalism when local newspapers started publishing his poems.

Working at the St. Louis Times

In 1829, Lovejoy became an editor at the St. Louis Times newspaper. This newspaper supported Henry Clay for president. Working at the Times helped him meet important community leaders. Many of them were part of the American Colonization Society. This group supported sending freed Black Americans to Africa. However, people like Frederick Douglass disagreed, saying that most African Americans were born in the U.S. and belonged there. Lovejoy also met lawyers and slaveholders like Edward Bates and Hamilton R. Gamble.

Lovejoy sometimes hired enslaved people to work at the newspaper. One of them was William Wells Brown. Brown later wrote that Lovejoy was "a very good man." He said Lovejoy helped him learn to read and write while he was enslaved.

Becoming a Minister

Lovejoy was always interested in religion. In 1832, he was influenced by meetings led by abolitionist David Nelson. Lovejoy decided to become a preacher. He sold his share of the Times newspaper and went back East to study at Princeton Theological Seminary. While there, he debated slavery. Even though he had been against abolitionism in the debate, he later asked his debate opponent to write articles for his new newspaper.

After graduating, he went to Philadelphia. He became an ordained minister of the Presbyterian Church on April 18, 1833.

St. Louis Observer Newspaper

In 1833, a group of Protestants in St. Louis offered to pay for a religious newspaper if Lovejoy would edit it. Lovejoy agreed. On November 22, 1833, he published the first issue of the St. Louis Observer. His articles criticized both the Catholic Church and slavery.

From 1833 to 1836, Lovejoy often published articles criticizing the Catholic Church. He argued that it went against American democracy. Local Catholics and clergy were upset and wrote their own articles in their newspaper, The Shepherd of the Times.

In 1834, the St. Louis Observer started writing more about slavery. This was a very sensitive topic. At first, Lovejoy didn't want to call himself an abolitionist. He didn't like the idea that abolitionism caused trouble. He called himself an "emancipationist" instead. In 1835, another newspaper suggested gradually ending slavery in Missouri. Lovejoy supported this idea in the Observer. But both newspapers soon found that even talking about ending slavery slowly caused strong disagreements.

Over time, Lovejoy became bolder in his views against slavery. He started calling for all enslaved people to be freed for religious and moral reasons. Lovejoy said that slavery was "demonstrably an evil." He wrote that it "sucks away the life-blood of society."

Threats and Violence

Lovejoy's strong views on slavery led to complaints and threats. People who supported slavery said that anti-slavery articles were against the interests of slaveholding states. Lovejoy was threatened with violence if he kept publishing anti-slavery content.

By October 1835, there were rumors that a mob would attack The Observer. A group of important people in St. Louis, including some of Lovejoy's friends, asked him to stop writing about slavery. Lovejoy was away at the time. The publishers said they would not print any more articles on slavery until he returned. Lovejoy disagreed with this. As tensions grew, Lovejoy refused to change his beliefs. He felt he might become a hero for the cause. He was asked to resign as editor, and he agreed. But then the new owners of the newspaper asked him to stay on as editor.

Lovejoy's Family Life

Lovejoy also worked as a traveling preacher. During his travels, he met Celia Ann French in St. Charles. She was the daughter of a lawyer. Elijah and Celia were married on March 4, 1835. Their son, Edward P. Lovejoy, was born in 1836. Their second child was born after Elijah's death but died as a baby. Elijah wrote to his mother about Celia: "My dear wife is a perfect heroine... never has she by a single word attempted to turn me from the scene of warfare and danger."

Moving to Illinois

In the summer of 1836, Lovejoy went to a church meeting in Pittsburgh. There, he met people who followed Theodore Dwight Weld, another abolitionist. Lovejoy was upset that the church was slow to fully support ending slavery. By this time, he fully accepted being called an "abolitionist."

Because of all the negative attention and two break-ins at his office in May 1836, Lovejoy decided to move his newspaper, The Observer, across the Mississippi River to Alton, Illinois. Alton was a large and successful town then. Even though Illinois was a free state, Alton was a place where slave catchers and pro-slavery groups were active. Many enslaved people tried to escape across the Mississippi River from Missouri into Illinois. Some people in Alton who supported slavery didn't want the town to become a safe place for escaped slaves.

On July 21, 1836, Lovejoy published a strong article criticizing how a judge handled a murder trial. He said the judge's actions seemed to excuse the murder. He also announced that his next newspaper issue would be printed in Alton. Before he could move his printing press, a mob broke into The Observer office and damaged it. Only one city official tried to stop them, and no police helped. Lovejoy packed what was left of his office to send to Alton. The printing press was left unguarded by the river overnight. Vandals destroyed it and threw the pieces into the Mississippi River.

The Alton Observer

Lovejoy became a pastor at Upper Alton Presbyterian Church. In 1837, he started a new newspaper called the Alton Observer. This paper also supported ending slavery. Lovejoy's views on slavery became even stronger. He called for a meeting to create an Illinois chapter of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Many people in Alton began to wonder if they should let Lovejoy keep printing his newspaper in their town. After an economic crisis in March 1837, some Alton citizens thought Lovejoy's views might be hurting their town's business. They worried that Southern states or even St. Louis might not want to trade with Alton if it had such a strong abolitionist.

Lovejoy held the Illinois Antislavery Congress at the Presbyterian church in Upper Alton on October 26, 1837. Two people who supported slavery, John Hogan and Illinois Attorney General Usher F. Linder, surprised supporters by showing up. Lovejoy's supporters were not happy, but the meeting was open to everyone.

On November 2, 1837, Lovejoy responded to threats in a speech. He said:

As long as I am an American citizen, and as long as American blood runs in these veins, I shall hold myself at liberty to speak, to write and to publisher whatever I please, being amenable to the laws of my country for the same.

Mob Attack and Death

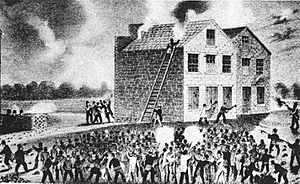

Lovejoy had bought a fourth printing press. He hid it in a warehouse owned by Winthrop Sargent Gilman and Gilford, who were local grocers. A mob, mostly from Missouri, attacked the building on the evening of November 6, 1837. People who supported slavery came to the warehouse where Lovejoy's press was hidden. The fight continued. According to the Alton Observer, the mob shot into the warehouse. When Lovejoy and his men shot back, they hit several people in the crowd, killing one man. After the attackers seemed to leave, Lovejoy opened the door. He was immediately hit by five bullets and died within minutes.

Elijah Lovejoy was buried in Alton Cemetery. His grave was not marked to prevent people from damaging it. The burial was kept small. In 1864, Thomas Dimmock found Lovejoy's grave. He arranged for a gravestone and helped start a group to create a monument for the editor. Dimmock gave the main speech when the monument was dedicated in 1897.

The Chicago Tribune newspaper wrote about the grave marking:

For many years Lovejoy's grave was unmarked and in danger of utter oblivion, until one who had known him in life, Thomas Dimmock of St. Louis, . . . marked the grave with the simple stone bearing he inscription: "Hic jacet Lovejoy. Jam parce depulto." "Here lies Lovejoy: now spare his grave." It was largely through the efforts of Mr. Dimmock that ten years ago the Lovejoy Monument Association was formed . . . .

Alton Riot Trial

Francis B. Murdoch, the district attorney of Alton, brought charges related to the riot in January 1838. He charged both the attackers and the people who defended the warehouse. He asked the Illinois Attorney General, Usher F. Linder, to help him.

Murdoch first charged Gilman, the warehouse owner, and eleven other defenders. They were accused of "unlawful defence" because their actions were "violently and tumultuously done." Gilman asked to be tried separately. The court agreed. The jury found Gilman "Not Guilty." The next morning, the charges against the other eleven defenders were dropped.

A new jury was chosen to hear the case against the attackers of the warehouse. Their trial started on January 19, 1838. The jury decided it was not possible to figure out who was responsible among all the suspects. They gave a verdict of "not guilty." The foreman of this jury had been part of the mob and was even hurt in the attack. The judge in the case also acted as a witness. These conflicts of interest are believed to have led to the "not guilty" verdict.

Lovejoy's Legacy and Honors

- Lovejoy was seen as a martyr by the movement to end slavery. His brother, Owen Lovejoy, became a leader of the Illinois abolitionists. Owen and his brother Joseph wrote a book about Elijah in 1838. It was shared widely among abolitionists. Because his death showed the growing tensions in the country, Lovejoy is sometimes called the "first casualty of the Civil War."

- Abraham Lincoln mentioned Lovejoy's murder in a speech in January 1838.

- John Brown was inspired by Lovejoy's death. He publicly declared, "Here, before God... from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery."

- A book about Lovejoy, Tide Without Turning: Elijah P. Lovejoy and Freedom of the Press, was published in 1958.

- Awards and scholarships:

- The Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award was created by Colby College in his honor. It is given each year to a journalist who has made important contributions to journalism. A building at Colby is also named after Lovejoy.

- In 2003, Reed College started the Elijah Parish and Owen Lovejoy Scholarship.

- Memorials and plaques:

- In 1897, the 110-foot tall Elijah P. Lovejoy Monument was built at Alton's City Cemetery.

- A plaque honoring Lovejoy is on a wall at Princeton Theological Seminary, his old school.

- He is the first person listed in the "Journalists Memorial" at the Newseum in Washington, D.C.

- Elijah Lovejoy has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

- Many places and institutions are named after him:

- The village of Brooklyn, Illinois, which is mostly African-American, is often called 'Lovejoy' in his honor.

- The Giddings-Lovejoy Presbytery of the Presbyterian Church (USA) was formed in 1985.

- Lovejoy Health Center in Albion, Maine, where he was born.

- The Lovejoy School in Washington, D.C., was named after him in 1870.

- Lovejoy Elementary School in Alton, Illinois.

- LoveJoy United Presbyterian Church in Wood River, Illinois.

- Lovejoy Library at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

Images for kids

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |