Theodore Dwight Weld facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

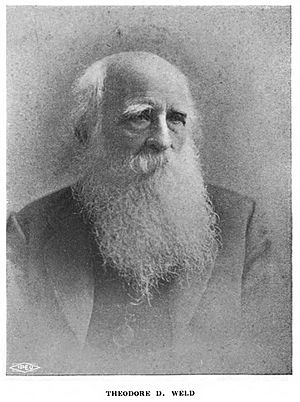

Theodore Dwight Weld

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 23, 1803 |

| Died | February 3, 1895 (aged 91) |

| Alma mater | Hamilton College |

| Occupation | Abolitionist, writer, teacher |

| Employer | Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions (Lewis and Arthur Tappan), American Anti-Slavery Society |

| Known for | One of Charles Grandison Finney's "Holy Band"; leader of Lane Rebels |

|

Notable work

|

American Slavery as It Is |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3 |

| Signature | |

Theodore Dwight Weld (born November 23, 1803 – died February 3, 1895) was a very important leader in the American abolitionist movement. This movement worked to end slavery in the United States. Theodore Weld was a writer, editor, speaker, and organizer from 1830 to 1844.

He is famous for helping to write the book American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses in 1839. This book showed the terrible truth about slavery. Harriet Beecher Stowe used parts of Weld's book when she wrote her famous novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Many people say Weld's book was the second most important book in fighting slavery, after Uncle Tom's Cabin. Weld kept fighting against slavery until it was finally ended by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.

A famous preacher named Lyman Beecher once said that Weld was "as eloquent as an angel, and as powerful as thunder." He meant that Weld spoke beautifully and strongly.

Contents

Early Life and Travels

Theodore Weld was born in Hampton, Connecticut. His father and grandfather were ministers. When he was 14, Weld took over his family's farm to earn money for school. He went to Phillips Academy from 1820 to 1822. He had to leave because his eyesight got bad.

A doctor told him to travel, so he started giving talks about how to improve memory. For three years, he traveled all over the United States, even in the South. This is where he saw slavery firsthand. In 1825, Weld and his family moved to Pompey, New York.

College and Activism

Weld later studied at Hamilton College in Clinton, Oneida County, New York. While there, he met Charles Grandison Finney, a famous preacher. Weld became Finney's follower. In Utica, New York, which was a center for the abolitionist movement, Weld became good friends with Charles Stuart.

Weld then went to the Oneida Institute of Science and Industry in 1827. He often traveled for two weeks at a time, giving talks about hard work, avoiding alcohol, and being a good person. He was known for being able to "hold listeners spellbound for three hours." By 1831, he was a well-known person in his area.

William Lloyd Garrison, a famous abolitionist, wrote that Weld was "destined to be one of the great men not of America merely, but of the world." He believed Weld had a powerful mind and strong moral character.

Working for Education and Change

In 1831, two wealthy brothers, Lewis and Arthur Tappan, asked Weld to work for them in New York. They created a group called the Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions. This group hired Weld to travel and speak about the benefits of combining physical work with studying.

Weld traveled over 4,500 miles in 1832, giving 236 public speeches. He even almost died when a river swept away his coach. During this time, Weld also found the location for Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati. He helped choose the teachers and even enrolled there as a student in 1833.

Fighting for Abolition

Weld saw slavery firsthand during his travels. He also read Garrison's newspaper, The Liberator. These experiences made him a strong abolitionist. He believed slavery should end completely and immediately.

In 1834, Weld convinced other students at Lane Seminary to support immediate abolition. He then invited the public to a series of talks about slavery. These talks, held over 18 evenings, showed the terrible realities of American slavery.

However, the seminary leaders did not like the students' anti-slavery activities. They made rules to stop discussions about slavery. Because of this, almost all the students, including Weld, left the seminary. They became known as the Lane Rebels. Many of them went to Oberlin Collegiate Institute. They insisted that Oberlin allow them to discuss any topic freely and admit Black students.

Weld chose not to become a professor at Oberlin. Instead, he became an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society in Ohio. He took a lower salary to do this important work.

Anti-Slavery Work and Family

Starting in 1834, Weld worked for the American Anti-Slavery Society. He recruited and trained people to fight against slavery. He helped convince important figures like Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher to join the cause. Weld became a key leader, working with the Tappan brothers and the Grimké sisters.

In 1836, Weld lost his voice from too much lecturing. He then became an editor for the American Anti-Slavery Society's books and pamphlets. He also edited a newspaper called The Emancipator from 1836 to 1840.

In 1838, Weld married Angelina Grimké, who was also a strong abolitionist and women's rights supporter. At their wedding, there were two ministers, one white and one Black. Weld publicly said he would not have any power over his wife except through love. Two formerly enslaved people, who had belonged to Angelina's father, were guests at the wedding.

Afterward, Weld, his wife, and her sister co-wrote the very important 1839 book American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses.

In 1840, Weld moved to Washington, D.C. He led a national effort to send anti-slavery petitions to Congress. He even helped John Quincy Adams when Congress tried to stop him from reading these petitions.

After showing how important it was to have an anti-slavery voice in Washington, Weld returned to private life. He and his wife spent the rest of their lives running schools and teaching in New Jersey and Massachusetts.

Schools for All

In 1854, Weld started a school in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. This school welcomed students of all races and genders. In 1864, he moved to Hyde Park, Massachusetts. There, he helped open another school in Lexington, Massachusetts that followed the same principles. At this school, Weld taught subjects like conversation, writing, and English literature.

Family Life

Theodore Weld was the son of Ludovicus Weld and Elizabeth Clark Weld. His brother, Ezra Greenleaf Weld, was a famous photographer who also supported the abolitionist movement.

Theodore Weld died at his home in Hyde Park, Massachusetts, on February 3, 1895.

Writings

- First annual report of the Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions (1833)

- The Power of Congress over the District of Columbia (1838)

- The Bible Against Slavery (1837)

- American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (with the Grimké sisters; 1839)

- Persons held to service, fugitive slaves, &c (1840)

- Slavery and the internal slave trade in the United States of North America (1841)

Legacy

- A student from Lane Seminary, Huntington Lyman, named his son Theodore Weld Lyman (born 1840) after Weld.

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |