Angelina Grimké facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

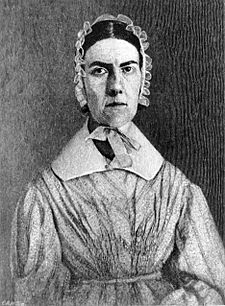

Angelina Emily Grimké

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | February 20, 1805 |

| Died | October 26, 1879 (aged 74) Hyde Park, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Politician, abolitionist, suffragist |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3 |

| Signature | |

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (born February 20, 1805 – died October 26, 1879) was an American hero. She was an abolitionist, which means she worked to end slavery. Angelina was also a political activist and fought for women's rights. She strongly supported the women's suffrage movement, which aimed to give women the right to vote.

Angelina and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were special. They were among the few white women from the Southern United States who became famous abolitionists. The sisters lived together for most of their adult lives. Angelina was married to another important abolitionist leader, Theodore Dwight Weld.

Even though Angelina grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, she and Sarah lived in the North as adults. Angelina became very well-known between 1835 and 1838. In 1835, William Lloyd Garrison published her letter in his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. In May 1838, she gave a powerful speech to abolitionists. Outside, a large, angry crowd threw stones at Pennsylvania Hall.

Angelina's ideas came from several places. She believed in natural rights theory, like those in the United States Declaration of Independence. She also used the U.S. Constitution and her Christian faith. Her own memories of the cruel slavery and racism she saw as a child in the South also shaped her views. Grimké declared that it was wrong to deny freedom to anyone. When people criticized her for speaking in public to mixed groups of men and women in 1837, she and Sarah strongly defended women's right to speak out and be part of political discussions.

In May 1838, Angelina married Theodore Dwight Weld. He was a very important abolitionist. They lived in New Jersey with her sister Sarah. They had three children: Charles Stuart (born 1839), Theodore Grimké (born 1841), and Sarah Grimké Weld (born 1844). To earn money, they ran two schools. The second school was in a special community called Raritan Bay Union. After the Civil War ended, the Grimké–Weld family moved to Hyde Park, Massachusetts. Angelina and Sarah were active members of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association.

Contents

Early Life and Beliefs

Angelina Grimké was born in Charleston, South Carolina. Her parents, John Faucheraud Grimké and Mary Smith, came from rich planter families. Her father was a lawyer, a judge, and a veteran of the Revolutionary War. He was a respected member of Charleston society. Her mother, Mary, was related to a former South Carolina Governor. Angelina's parents owned a plantation and many slaves.

Angelina was the youngest of 14 children. Her father believed that women should follow men's lead. He only provided formal education for his sons. However, the boys shared their lessons with their sisters.

Childhood and Faith

Angelina's parents strongly believed in the traditional values of their wealthy Charleston society. Her mother did not let the girls socialize outside their elite social circles. Her father owned slaves his entire life.

Angelina, nicknamed "Nina," was very close to her older sister Sarah Moore Grimké. When Sarah was 13, she convinced her parents to let her be Angelina's godmother. The two sisters remained close throughout their lives. They lived together for most of their lives, with only a few short times apart.

Even as a child, Angelina was described as very curious and confident. Historian Gerda Lerner wrote that Angelina never thought she should obey her male relatives. She also didn't think anyone could be better than her just because she was a girl. Angelina was naturally inquisitive and spoke her mind. This often upset her traditional family and friends.

When she was 13, Angelina was supposed to be confirmed in the Episcopal Church. But she refused to say the creed of faith. She felt she could not agree with it. In April 1826, at age 21, Angelina became a Presbyterian.

Angelina was an active member of her Presbyterian church. She loved studying the Bible and teaching others. She taught a Sabbath school class. She also held religious services for her family's slaves. Her mother at first did not like this, but later joined in. Grimké became good friends with her pastor, Rev. William McDowell. Both Angelina and McDowell were against slavery. They believed it was wrong and went against Christian law and human rights.

In 1829, Angelina spoke at a church meeting about slavery. She said everyone in the church should openly condemn it. Her audience respected her, but they turned down her idea. By this time, the church had accepted slavery. They found reasons for it in the Bible. They told Christian slaveholders to be kind to their slaves. But Angelina lost faith in the Presbyterian church. In 1829, she was officially removed from the church. With Sarah's help, Angelina joined the Quaker faith. The Quaker community in Charleston was very small. Angelina tried to change her friends and family's views. But her comments often offended people. She decided she could not fight slavery while living in the South. So, she followed her older sister Sarah to Philadelphia.

Becoming an Activist

The Grimké sisters joined a Quaker group in Philadelphia. At first, they didn't know much about political issues. They only read The Friend, a Quaker newspaper. This paper gave little information about current events. So, Angelina was not aware of many important events or people at the time.

Angelina lived with her widowed sister, Anna Grimké Frost, for a while. Angelina noticed that widowed women had few choices. Most had to remarry. Upper-class women usually did not work outside the home. Angelina realized how important education was. She decided to become a teacher.

Over time, she became frustrated. The Quaker community was not doing enough about slavery. She started reading more anti-slavery writings. These included The Emancipator and William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator. Sarah and the traditional Quakers did not like Angelina's interest in radical abolitionism. But Angelina became more and more involved. She started going to anti-slavery meetings and lectures. In 1835, she joined the new Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society.

Speaking Out

In the fall of 1835, violence broke out when abolitionist George Thompson spoke publicly. William Lloyd Garrison wrote an article in The Liberator to calm the angry crowds. Angelina was inspired by Garrison's work. She wrote him a personal letter about abolitionism and mob violence. She also told him how much she admired him.

Garrison was so impressed that he published her letter in The Liberator. He praised her passion and ideas. This letter made Angelina well-known among abolitionists. But it also caused problems with her former Quaker group. They did not like such radical activism, especially from a woman. Sarah Grimké asked her sister to take back the letter. She worried that the publicity would make Angelina an outcast from the Quaker community. Angelina was embarrassed at first, but she refused to take back the letter. It was later printed in other newspapers.

In 1836, Grimké wrote "An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South." In this essay, she urged Southern women to ask their state leaders and church officials to end slavery. The American Anti-Slavery Society published it. Many experts see this as a key moment in Grimké's work.

In the fall of 1836, the Grimké sisters were invited to New York City. They attended a two-week training conference for anti-slavery agents. They were the only women there. They met Theodore Dwight Weld, who was a trainer and a leading agent. Angelina and Theodore later married. That winter, the sisters were asked to speak at women's meetings. They also helped organize women's anti-slavery groups in New York City and New Jersey. In May 1837, they joined other leading women abolitionists. They held the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women. This meeting aimed to spread women's anti-slavery efforts to other states.

After this convention, the sisters went to Massachusetts. People there accused New England abolitionists of exaggerating the truth about slavery. So, the sisters were asked to speak throughout New England. They shared their firsthand knowledge of slavery. Their meetings were open to men from the start. This was done to reach both men and women. It also helped to break down barriers for women speakers. Women were going against social rules by speaking in public. In response, a group of Massachusetts ministers condemned women's public work. They urged churches to close their doors to the Grimkés.

As the sisters spoke in Massachusetts in 1837, the debate grew. It was about women's rights and duties, both in and outside the anti-slavery movement. Angelina wrote "Letters to Catharine Beecher" in response to Catharine Beecher's criticisms. These letters were printed in newspapers and then as a book in 1838. Sarah Grimké also wrote Letters on the Province of Woman. These letters strongly defended women's right to participate equally with men in all such work.

In February 1838, Angelina spoke to a committee of the Massachusetts State Legislature. She was the first woman in the United States to speak to a legislative body. She spoke against slavery. She also defended women's right to petition, both as a moral duty and a political right. One abolitionist, Robert F. Wallcut, said Angelina's calm and powerful speaking held everyone's attention.

On May 17, 1838, two days after her marriage, Angelina spoke at Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia. This was a gathering of abolitionists of all races. As she spoke, an angry crowd outside grew louder. They shouted threats at Angelina and others. Rioters began throwing bricks and stones, breaking the hall's windows. Angelina kept speaking. After her speech, the diverse group of women left the building arm-in-arm. The next day, Pennsylvania Hall was destroyed by arson. Angelina was the last person to speak in the Hall.

Angelina's speeches criticized not only Southern slaveholders. She also criticized Northerners who quietly supported slavery. They bought products made by slaves. They also did business with slave owners in the South. Her speeches faced much opposition. This was because Angelina was a woman and an abolitionist.

Important Writings

Two of Grimké's most famous works were "An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South" and her letters to Catharine Beecher.

"An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South" (1836)

"An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South" was published by the American Anti-Slavery Society. It was special because it was the only appeal written by a Southern woman to other Southern women about ending slavery. Angelina hoped that Southern women would listen to someone from their own region. The essay was very personal and used simple, strong language. Radical abolitionists praised it. However, her former Quaker community criticized it. It was even publicly burned in South Carolina.

"The Appeal" made seven main points:

- Slavery goes against the Declaration of Independence.

- Slavery goes against the first human rights given in the Bible.

- The idea that slavery was predicted does not excuse slaveholders.

- Slavery was never meant to exist under old family laws.

- Slavery never existed under ancient Hebrew Biblical law.

- Slavery in America "turns a person into a thing."

- Slavery goes against the teachings of Jesus Christ.

After explaining these points, Grimké said why she was speaking to Southern women. She knew women could not make laws. But she said women had four duties: to read, to pray, to speak, and to act. Women might not have political power, but they are "the wives and mothers, the sisters and daughters of those who do." She encouraged women to speak out against slavery. She told them to face any difficulties that might come from it. She believed women were strong enough to do this. She saw women as powerful political actors on the issue of slavery.

Grimké also explained what she believed slavery was. She said, "A person cannot rightfully own another person as property." She repeated ideas from the Declaration of Independence about human equality. Grimké argued that "a person is a person, and as a person has rights that cannot be taken away, including the right to personal freedom."

The essay also showed Grimké's strong belief in education for everyone, including women and slaves. Her Appeal stressed that women should educate their slaves or future workers. She wrote, "If they stay with you, teach them, and have them taught basic English education; they have minds and those minds should be improved."

Letters to Catharine Beecher

Grimké's Letters to Catharine Beecher were a series of essays. They were written in response to Beecher's An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism with Reference to the Duty of American Females. Beecher's essay was written directly to Grimké. Angelina wrote her responses with the help of her future husband, Weld. They were published in The Emancipator and The Liberator. Then, they were printed together as a book in 1838.

Beecher's essay argued that women should not be involved in the abolitionist movement. She believed women were meant to be below men. She said, "Men are the right people to make appeals to the rulers they choose... [females] are certainly out of their place trying to do it themselves." Grimké's responses defended both abolitionism and women's rights. Her arguments against slavery were similar to points Weld made in the Lane Seminary debates. Grimké openly criticized the American Colonization Society. She wrote about her respect for people of color. She said, "I love the colored Americans, and I want them to stay in this country. To make it a happy home for them, I am trying to talk down, and write down, and live down this terrible prejudice."

Grimké's Letters are seen as an early argument for feminism. Only two of the letters directly discuss feminism and women's right to vote. Letter XII sounds a bit like the Declaration of Independence. It also shows Grimké's religious values. She argued that all humans are moral beings and should be judged that way, no matter their gender. She said, "Measure her rights and duties by the perfect standard of moral being... and then the truth will be clear: whatever it is morally right for a man to do, it is morally right for a woman to do. I know only human rights—I know nothing of men's rights and women's rights; for in Christ Jesus, there is no male or female. I strongly believe that until this idea of equality is accepted and put into practice, the Church cannot truly change the world."

Grimké directly answered Beecher's traditional view of women's place. She said, "I believe it is a woman's right to have a say in all the laws and rules that govern her, whether in Church or State. And that the current ways society is set up, on these points, are a violation of human rights. They are a clear taking of power, a forceful seizure of what is sacredly and rightfully hers."

American Slavery as It Is

In 1839, Angelina, her husband Theodore Dwight Weld, and her sister Sarah published American Slavery as It Is. This book was like an encyclopedia of how slaves were mistreated. It became the second most important abolitionist book. The most important was Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe, who said she was inspired by American Slavery as It Is.

Personal Life

In 1831, Angelina was courted by Edward Bettle. He was from a well-known Quaker family. Diaries show that Bettle wanted to marry Grimké. Sarah supported this idea. However, in the summer of 1832, a large cholera outbreak happened in Philadelphia. Grimké agreed to take in Bettle's cousin, Elizabeth Walton, who was dying of the disease. Bettle, who visited his cousin often, caught the disease and died soon after. Grimké was heartbroken. She put all her energy into her activism.

Grimké first met Theodore Dwight Weld in October 1836. This was at an abolitionist training meeting in Ohio led by Weld. She was very impressed with his speeches. She wrote to a friend that he was "a man chosen by God and wonderfully able to speak for the oppressed." In the two years before they married, Weld encouraged Grimké's activism. He helped arrange many of her lectures and the publication of her writings. They told each other they loved each other in letters in February 1838. On May 14, 1838, two days before her speech at Pennsylvania Hall, they were married in Philadelphia. A black minister and a white minister performed the ceremony.

After their marriage, Grimké's health declined. She eventually focused more on home life. Sarah lived with the couple in New Jersey. The sisters continued to write to and visit their friends in the abolitionist and women's rights movements. They ran a school in their home. Later, they ran a boarding school at Raritan Bay Union, a special community. At the school, they taught the children of other famous abolitionists, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

After the Civil War, they helped their two mixed-race nephews. These were the sons of their brother Henry W. Grimké and an enslaved woman he owned. The sisters paid for Archibald Henry Grimké and Rev. Francis James Grimké to attend Harvard Law School and Princeton Theological Seminary. Archibald became a lawyer and later an ambassador to Haiti. Francis became a Presbyterian minister. Both became important civil rights activists. Archibald's daughter, Angelina Weld Grimké, became a poet and author.

Legacy

History of Woman Suffrage (1881) is dedicated to the memory of Sarah and Angelina Grimké, among others.

Angelina Grimké, like her sister Sarah, has received more recognition in recent years. Grimké is honored in Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party, a famous art installation.

In 1998, Grimké was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame. She is also remembered on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail.

In November 2019, a newly rebuilt bridge in Hyde Park was named for the Grimké sisters. It is now called the Grimké Sisters Bridge.

In culture

Angelina Grimké Weld is mentioned many times in Ain Gordon's 2013 play If She Stood. The characters Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Weld Grimké talk about her.

Angelina Grimké Weld is also an important character in Sue Monk Kidd's novel The Invention of Wings. This book focuses on the stories of Sarah Moore Grimké and a slave in the Grimké household named Handful.

See also

In Spanish: Angelina Grimké para niños

In Spanish: Angelina Grimké para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |