Judy Chicago facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Judy Chicago

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Judith Sylvia Cohen

July 20, 1939 Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of California, Los Angeles |

| Known for | |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Movement |

|

| Awards | Tamarind Fellowship (1972), Time magazine's "100 Most Influential People" (2018), Visionary Woman award from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (2019) |

| Patron(s) |

|

Judy Chicago (born Judith Sylvia Cohen; July 20, 1939) is an American feminist artist, teacher, and writer. She is famous for her large art projects. These projects often explore the role of women in history and culture. They also look at themes of birth and creation.

In the 1970s, Judy Chicago started the first feminist art program in the United States. This program was at California State University, Fresno. It helped kickstart feminist art and art education. Her work has been featured in many publications worldwide. This shows her big impact on the global art community. Many of her books have also been published in other countries.

Chicago uses many different art skills. She combines needlework with things like welding and fireworks. Her most famous artwork is The Dinner Party. This piece is now permanently displayed at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum. The Dinner Party celebrates the achievements of women throughout history. It is seen as the first major feminist artwork. Other important projects by Chicago include International Honor Quilt, Birth Project, PowerPlay, and The Holocaust Project. In 2018, Time magazine named her one of the "100 Most Influential People."

Contents

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Growing Up in Chicago

Judy Chicago was born Judith Sylvia Cohen in Chicago, Illinois, in 1939. Her parents were Arthur and May Cohen. Her father came from a long line of rabbis. But he chose to become a labor organizer and a Marxist. He worked at night and took care of Judy during the day. Her mother, May, was a former dancer and worked as a medical secretary.

Arthur's involvement in the American Communist Party and his support for workers' rights shaped Judy's beliefs. During the McCarthy era, her father was investigated. This made it hard for him to find work. It caused a lot of stress for the family. He passed away in 1953. Judy's mother did not talk about his death. Judy struggled with this loss for many years.

Discovering Art

May Cohen loved the arts. She shared this passion with her children. Judy started drawing at age three. She took classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. By age five, Judy knew she wanted to "never do anything but make art." She continued art classes through her childhood. After high school, she went to UCLA on a scholarship.

Education and Early Career

College Years and Personal Changes

At UCLA, Judy became active in politics. She designed posters for the UCLA NAACP chapter. She later became its secretary. In 1959, she met Jerry Gerowitz. She moved in with him and had her own art studio for the first time. They traveled to New York. Then they returned to Los Angeles in 1960 so she could finish her degree.

Judy married Jerry Gerowitz in 1961. She earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1962. Jerry died in a car crash in 1963. This was a very difficult time for Judy. She received her Master of Fine Arts from UCLA in 1964.

Exploring New Artistic Ideas

In graduate school, Chicago created abstract art. These early works were called Bigamy. They explored themes of loss and connection. Her professors, mostly men, were surprised by these pieces. Even though her art used certain forms, Chicago did not focus on gender politics at this time.

In 1965, Chicago had her first solo art show. It was at the Rolf Nelson Gallery in Los Angeles. She was one of only four women artists in the show. In 1968, she was asked why she didn't join a "California Women in the Arts" exhibition. She replied that she would not show in groups defined by labels like "Woman" or "Jewish." She hoped for a future without such labels.

Chicago also experimented with ice sculpture. These sculptures represented "the preciousness of life." This was another way she thought about her husband's death.

In 1969, the Pasadena Art Museum showed her sculptures and drawings. Art in America magazine said her work was leading the conceptual art movement. Chicago described her early art as minimalist. She said she was trying to be "one of the boys." She also tried performance art. She used fireworks to create "atmospheres" with colored smoke outdoors.

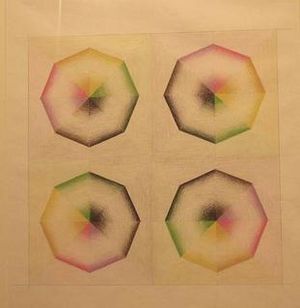

During this time, Chicago also explored personal themes in her art. She created the Pasadena Lifesavers series. These were abstract paintings on Plexiglas. The colors blended to make shapes that seemed to move and change. This series was a major turning point in her art.

Chicago later shared that her early career was very challenging. The art world was not welcoming to women. But she used that time to build her skills. She developed her use of color and her ambition. She had a strong desire to create art and make a difference.

Choosing a New Name

As Judy became a known artist, she felt less connected to her birth name, Cohen. She also felt disconnected from her married name, Gerowitz, after her husband's death. She wanted a name that was independent of men.

In 1965, she married sculptor Lloyd Hamrol. They later divorced in 1979.

Gallery owner Rolf Nelson nicknamed her "Judy Chicago." This was because of her strong personality and Chicago accent. She decided this would be her new name. She legally changed her last name. To celebrate, she posed as a boxer for an exhibition invitation. She wore a sweatshirt with her new name. At her 1970 solo show, she put up a banner. It said she was giving up names given by male dominance. She chose her own name, Judy Chicago. An advertisement with this statement also appeared in Artforum magazine.

Career Highlights

The 1970s and Feminist Art

Judy Chicago is considered one of the "first-generation feminist artists." This group includes artists like Mary Beth Edelson and Suzanne Lacy. They helped develop feminist art in the early 1970s.

In 1970, Chicago began teaching at Fresno State College. She wanted to teach women how to express female perspectives in their art. She started the first women's art class in the fall of 1970. This became the Feminist Art Program in 1971. It was the first program of its kind in the United States. Fifteen students studied with Chicago. They rented an off-campus studio. There, they created art, read, and discussed their life experiences. These discussions influenced their art.

Later, Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro started the Feminist Art Program at California Institute of the Arts. Chicago's image was included in the famous 1972 poster, Some Living American Women Artists.

In 1973, Chicago helped found the Los Angeles Woman's Building. This was an art school and exhibition space. It housed the Feminist Studio Workshop. The founders wanted to create a new kind of art and artist. They wanted art to come from the lives and feelings of women. During this time, Chicago created abstract spray-painted canvases. These works explored the meaning of "feminine."

Her first book, Through the Flower (1975), shared her journey to find her identity as a woman artist.

Womanhouse

Womanhouse was a project by Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. It started in 1971 when Chicago taught at the California Institute of the Arts. In 1972, they chose 21 female students for the Feminist Art Program. They wanted a big group project. It would involve female artists talking about their experiences as women.

The idea for Womanhouse came from discussions about the home. Women were traditionally linked to the home. The artists wanted to show the realities of womanhood within the home. Chicago believed female students often hesitated to push their limits. This was because they were not used to tools or seeing themselves as working artists. The goal of the program was to help women become artists. It aimed to help them create art from their experiences as women.

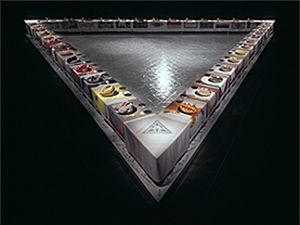

The Dinner Party

Inspired by her studies, Chicago created The Dinner Party. This artwork is now at the Brooklyn Museum. It took her five years to make and cost about $250,000. Chicago designed a large triangular dining table. It measures 48 feet by 43 feet by 36 feet. It has 39 place settings. Each setting honors a historical or mythical female figure. These include artists, goddesses, and activists. Thirteen women are represented on each side of the table. The table runners are embroidered in the style of each woman's time. Many other women's names are carved into the "Heritage Floor" beneath the table.

Over 400 people, mostly women, helped create the project. They volunteered for needlework and sculpture. The Dinner Party was first a traveling exhibition. Chicago's non-profit, Through the Flower, helped cover the costs.

Some art critics did not like the work. But the public loved it. Chicago showed her work in six countries. Over a million people saw her art.

Birth Project and PowerPlay

From 1980 to 1985, Chicago created Birth Project. This artwork used images of childbirth. It celebrated women's role as mothers. Chicago was inspired because there was little art showing birth. She famously said, "If men could give birth, there would be millions of representations of the crowning." The project reimagined the Genesis creation narrative. This story focused on a male god creating a male human without a woman. Chicago saw the piece as revealing a "primordial female self." About 150 needleworkers from different countries helped. They worked on 100 panels using quilting, macrame, and embroidery. The piece is so large that it is rarely shown all at once. Most of the Birth Project pieces are at the Albuquerque Museum.

Chicago herself was not interested in being a mother. She admired women who chose that path. But she felt it was not right for her. She said in 2012, "There was no way on this earth I could have had children and the career I've had."

Around the same time, Chicago started PowerPlay in 1982. This was a series of large paintings, drawings, and reliefs. Both Birth Project and PowerPlay explored subjects rarely shown in Western art. PowerPlay was inspired by Chicago's trip to Italy. She saw famous Renaissance artworks there. She wanted to explore masculinity in a similar grand style.

The titles of the works, like Crippled by the Need to Control or Disfigured by Power, show Chicago's focus on certain male behaviors. But the bright colors and images of faces and bodies also show vulnerability. Chicago's husband, Donald Woodman, posed for some pieces. She wanted to express her feelings about how some men act.

By showing male bodies, Chicago offered a different view. She said she didn't want to keep using the female body to show all emotions. She wondered what feelings the male body could express.

The Holocaust Project

In the mid-1980s, Chicago's focus changed. She began to explore male power and helplessness through the Holocaust. The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985–93) was a collaboration with her husband, photographer Donald Woodman. They married on New Year's Eve 1985. Chicago started to explore her own Jewish heritage after meeting Woodman.

Chicago met poet Harvey Mudd, who wrote a long poem about the Holocaust. Chicago wanted to illustrate it. But she decided to create her own visual and written work instead. She worked with her husband for eight years on the piece. The project shows victims of the Holocaust. It was created during a time of personal loss for Chicago. Her brother and mother both passed away.

Chicago used the Holocaust to explore themes of injustice and human cruelty. To prepare, Chicago and Woodman watched the documentary Shoah. They also looked at photos and writings about the Holocaust. They visited concentration camps and Israel. Chicago also connected other issues to the work, like environmental concerns. She wanted to link modern problems to the moral questions of the Holocaust. This part of the work caused some discussion within the Jewish community.

The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light has sixteen large artworks. They use many different materials. These include tapestry, stained glass, metal, wood, photography, and painting. The exhibit covers 3000 square feet. It ends with a piece showing a Jewish couple at Sabbath. The work was first shown in October 1993 at the Spertus Museum in Chicago. Most of the work is now at the Holocaust Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Later Works and Recognition

In 1994, Chicago started Resolutions: A Stitch in Time. She completed this series over six years. It was shown at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York.

In 1996, Chicago and Woodman moved to the Belen Hotel in Belen, New Mexico. Woodman had spent three years turning it into a home.

In 1999, Chicago received an award from UCLA. She also received honorary degrees from several universities. In 2004, she received a Visionary Woman Award. In 2008, she was honored for Women's History Month.

In 2011, Chicago returned to Los Angeles for an exhibition. She also performed a firework installation at Pomona College. She had done similar performances there in the 1960s. Chicago also gave her collection of feminist art educational materials to Penn State University.

In 2012, Chicago had two solo exhibitions in the United Kingdom. One was in London and another in Liverpool. The Liverpool exhibition included the launch of her book about Virginia Woolf. Writing has become an important part of her career. That year, she also received a Lifetime Achievement Award.

She was interviewed for the 2018 film !Women Art Revolution. In an interview with Gloria Steinem in 2018, Chicago said her goal as an artist is to create images where the female experience leads to universal understanding.

In 2021, she was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame. A major exhibition, Judy Chicago: A Retrospective, was shown at the De Young Museum in San Francisco in 2021. This was her first big retrospective. Her work was also part of the 2021 exhibition Women in Abstraction at the Centre Pompidou.

In 2022, Chicago worked with Nadya Tolokonnikova. They turned her What if Women Ruled the World? series into a project using blockchain. They hoped to create a community focused on gender rights.

Chicago always tries new things in her art. Early in her career, she learned to air-brush at a car-body school. She has also worked with glass. She believes in taking risks. She says she is not driven by career success. She would never just repeat what sold well.

From October 2023 to early March 2024, Chicago's work was featured at the New Museum in New York City. The exhibition was called Judy Chicago: Herstory.

Judy Chicago's art is in many museum collections. These include The British Museum, The Brooklyn Museum, and The National Museum of Women in the Arts. Her personal papers are at the Schlesinger Library. Her collection of women's history books is at the University of New Mexico.

Artistic Style and Collaboration

Chicago found inspiration in the "ordinary" woman. This was a key idea in the early 1970s feminist movement. This influenced her work, especially The Dinner Party. She was fascinated by textile work and crafts. These were often linked to women's culture.

Chicago also taught herself "macho arts." She took classes in auto body work, boat-building, and pyrotechnics. From auto body work, she learned spray painting. This helped her combine color and surface in her later art. Boat building skills helped her sculpture. Pyrotechnics were used for fireworks in her performances. These skills allowed her to use fiberglass and metal in her sculptures. She also learned porcelain painting for The Dinner Party. Chicago added stained glass to her skills for The Holocaust Project. Photography became more important in her work as her relationship with photographer Donald Woodman grew. Since 2003, Chicago has also been working with glass.

Working with others is a big part of Chicago's art. The Dinner Party, Birth Project, and Resolutions were all made with hundreds of volunteers. These volunteers often had skills in "traditional" women's arts, like textile arts. Chicago always makes sure to recognize her assistants as collaborators.

Through the Flower Organization

In 1978, Chicago started Through the Flower. This is a non-profit feminist art organization. Its goal is to teach people about the importance of art. It also shows how art can highlight women's achievements. Through the Flower also takes care of Chicago's artworks. It stored The Dinner Party before it found a permanent home. The organization also kept The Dinner Party Curriculum. This curriculum helps educate people about feminist art ideas. The online part of the curriculum was given to Penn State University in 2011.

Teaching Art to Students

Judy Chicago noticed sexism in art schools and museums in the 1960s. She was studying at UCLA. At first, she tried to fit in with male artists. She used heavy industrial materials and dressed in a "masculine" way. But she grew angry as she saw how society did not see women as professional artists. She used this energy to strengthen her feminist beliefs as a person and teacher.

Most art teachers focused on technique and color. But Chicago focused on the meaning and social importance of art. She especially focused on feminism. She valued art based on research, social views, or experience. She wanted her students to become artists without giving up what womanhood meant to them.

Chicago developed a way of teaching art. She encouraged students to explore "female-centered content." She believed the teacher should guide students. They should help students find their own ideas and turn them into art. She calls her teaching method "participatory art pedagogy."

The art made in the Feminist Art Program and Womanhouse showed new perspectives on women's lives. These topics had often been avoided in society and art. In 1970, Chicago started the Feminist Art Program at California State University, Fresno. She also led other teaching projects that ended with art exhibitions. These included Womanhouse with Miriam Schapiro at CalArts. Many students from Judy Chicago's projects became successful artists. These include Suzanne Lacy, Faith Wilding, and Nancy Youdelman.

In the early 2000s, Chicago organized her teaching style into three parts. These were preparation, process, and art-making. In the preparation phase, students found a personal concern. Then they researched it. In the process phase, students discussed materials and content in a group. Finally, in the art-making phase, students created their art.

In 2022, Judy Chicago and Donald Woodman returned to teaching. This was 50 years after Womanhouse first opened. Wo/Manhouse 2022 was in Belen, New Mexico. It featured 19 artists exploring gender roles and identity. The project was helped by Nancy Youdelman, who was part of the original Womanhouse.

Books by Judy Chicago

- The Dinner Party: A Symbol of our Heritage. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday (1979). ISBN: 0-385-14567-5.

- with Susan Hill. Embroidering Our Heritage: The Dinner Party Needlework. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday (1980). ISBN: 0-385-14569-1.

- The Birth Project. New York: Doubleday (1985). ISBN: 0-385-18710-6.

- Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist. New York: Penguin (1997). ISBN: 0-14-023297-4.

- Kitty City: A Feline Book of Hours. New York: Harper Design (2005). ISBN: 0-06-059581-7.

- Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist. Lincoln: Authors Choice Press (2006). ISBN: 0-595-38046-8.

- with Frances Borzello. Frida Kahlo: Face to Face. New York: Prestel USA (2010). ISBN: 3-7913-4360-2.

- Institutional Time: A Critique of Studio Art Education. New York: The Monacelli Press (2014). ISBN: 9781580933667.

- The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago. Thames & Hudson USA (2021). ISBN: 0500094381

See also

In Spanish: Judy Chicago para niños

In Spanish: Judy Chicago para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |