Carrie Chapman Catt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Carrie Chapman Catt

|

|

|---|---|

Catt around 1913

|

|

| Born |

Carrie Clinton Lane

January 9, 1859 Ripon, Wisconsin, US

|

| Died | March 9, 1947 (aged 88) |

| Education | Iowa State University (1880) |

| Spouse(s) |

Leo Chapman

(m. 1885; George Catt

(m. 1890; |

| Partner(s) | Mary Garrett Hay |

| Signature | |

Carrie Chapman Catt (born Carrie Clinton Lane; January 9, 1859 – March 9, 1947) was an important American leader. She worked hard to get women the right to vote. This right was given by the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920.

Catt was the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) twice. She led this group from 1900 to 1904 and again from 1915 to 1920. After women won the right to vote, she started the League of Women Voters in 1920. She also founded the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1904. This group is now called the International Alliance of Women. Catt was a very well-known woman in the United States during the early 1900s.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Carrie Clinton Lane was born on January 9, 1859, in Ripon, Wisconsin. Her parents were Maria Louisa and Lucius Lane. When Carrie was seven, her family moved to Charles City, Iowa. As a child, she loved science and dreamed of becoming a doctor.

After finishing high school in 1877, she went to Iowa Agricultural College. This school is now called Iowa State University. Her father did not want her to go to college at first. But he eventually agreed, though he only paid for some of her costs.

To pay for school, Carrie worked hard. She washed dishes, worked in the school library, and taught at country schools during breaks. In her first year, there were 27 students, and only six were girls. Carrie joined a student group called the Crescent Literary Society. This group helped students improve their speaking skills.

At first, only men were allowed to speak freely in meetings. But Carrie demanded to speak too. This led to a big discussion, and soon, women in the group gained the right to speak. Carrie was also part of Pi Beta Phi, a sorority. She started a debate club just for girls. She also pushed for women to be part of military training.

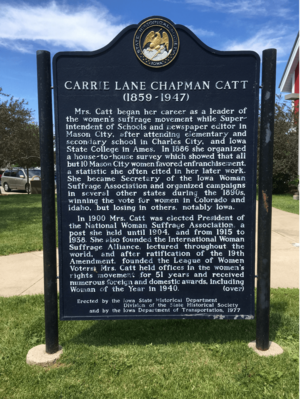

Carrie graduated on November 10, 1880, with a science degree. She was the only woman in her graduating class. After college, she worked as a law clerk. Then she became a teacher. In 1885, she became the superintendent of schools in Mason City, Iowa. She was the first woman to hold this job in the district.

In February 1885, Carrie married Leo Chapman, a newspaper editor. She stayed on her family farm in Iowa while Leo went to California to find work. Carrie got a telegram saying Leo was sick with typhoid fever. She traveled to California, but learned he had died in August 1886. She stayed in San Francisco for a while, writing articles and selling newspaper ads. But she returned to Iowa in 1887.

In 1890, she married George Catt, a rich engineer and a fellow graduate from Iowa State University. George encouraged her to get involved in the women's suffrage movement. Their marriage allowed her to travel a lot each year to campaign for women's right to vote.

Leading the Fight for Women's Vote

National American Woman Suffrage Association

Early Work for Suffrage

In 1887, Carrie returned to Charles City, Iowa. She joined the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association. From 1890 to 1892, she helped organize the Iowa group. During this time, she also started working with the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). She spoke at their meeting in Washington D.C. in 1890.

In 1892, Susan B. Anthony, a famous suffrage leader, asked Carrie to speak to Congress. Carrie spoke about the idea of a new law to give women the right to vote.

Carrie worked on her first suffrage campaign in South Dakota in 1890, but it failed. Then, she was asked to lead the campaign in Colorado. She arrived in Denver in September 1893. For two months, she traveled over a thousand miles across Colorado. She visited 29 counties. In November 1893, Colorado passed women's suffrage. It was the second state to let women vote. It was the first state where women won the right to vote by a popular vote of the people.

By 1895, Carrie suggested big changes for NAWSA. She said the group needed better organization. She then led a new "Organization Committee." This committee had a large budget and became very important for women's suffrage in the United States.

In 1896, NAWSA had a big discussion about Elizabeth Cady Stanton's book, The Woman's Bible. This book questioned old religious ideas that women were not as good as men. Many NAWSA members worried the book would hurt the suffrage movement. Carrie and Susan B. Anthony tried to talk to Stanton before the book came out. But Stanton did not change her mind. Carrie supported a statement saying NAWSA had no official link to the book.

At the 1898 NAWSA meeting, Mary Church Terrell, an African American activist, was a great speaker. She and Carrie became friends and stayed friends for life.

First Time as President (1900–1904)

In 1900, Carrie Catt became the president of NAWSA. Susan B. Anthony chose her as her replacement. Anthony knew Carrie had the skills to lead the movement. Her election was almost unanimous. Carrie served as president until 1904. She then stepped down to care for her sick husband, George Catt, who died in 1905.

In her first year as president, she led a group to the 1900 Republican Party meeting. The suffragists were allowed to speak for 10 minutes. The Democrats did not listen to them at all. That year, a second campaign for women's suffrage failed in Oregon. In 1902–1903, Carrie worked on a campaign in New Hampshire. It was very cold, and they lost the vote.

In 1902, Carrie called for an international meeting of women. This meeting happened at the same time as the NAWSA meeting. Seven of the eight countries where women could vote sent people. People from Chile, Hungary, Russia, Turkey, and Switzerland also came. Carrie and two other women wrote a "Declaration of Principles." Everyone signed it. It said: "Men and women are born equally free and independent... equally entitled to the free exercise of their individual rights and liberty." This meeting started the International Woman Suffrage Alliance. This group is still active today.

At the NAWSA meeting in New Orleans in 1903, Carrie and Anthony were criticized. The newspapers attacked them for allowing Black members in NAWSA. Southern members gave speeches saying only white women should vote. Carrie replied that the problem of race was for the whole country to solve together. She said, "Let us try to get nearer together and to understand each other's ideas on the race question and solve it together."

Second Time as President (1915–1920)

Carrie Catt was elected president of NAWSA again in 1915. Under her leadership, the group grew bigger and stronger. In 1916, at a meeting in Atlantic City, New Jersey, she shared her "Winning Plan." This plan aimed to get a national law for women's suffrage. It also planned for states to work towards this goal.

Carrie's plan had four parts. First, states where women could vote for president would ask their lawmakers to support a national law. Second, women in other states would try to get suffrage through state laws. Third, suffragists in most states would push for presidential voting rights. Fourth, Southern states would work for primary election voting rights.

Under Carrie's leadership, the movement focused on New York state first. Before 1917, only western states had given women the right to vote. A campaign in New York failed in 1915. But Carrie worked even harder. In 1917, New York state approved women's suffrage. Even though Carrie could now vote fully in New York, she kept working for a national law.

Also in 1917, Woodrow Wilson, the President, asked Congress to declare war on Germany. Both the Senate and House agreed to enter World War I. Carrie made a difficult choice to support the war effort. This changed how the public saw suffragists. People now saw them as patriotic. President Wilson supported the suffrage movement in January 1918.

On January 10, 1918, the House voted on the suffrage law. It passed by just one more vote than needed. The next day, Carrie asked all state suffrage leaders to start working to win over U.S. Senators. The Senate finally voted on October 1, 1918. The proposed law lost by two votes. World War I ended on November 11, 1918.

During a second vote in the Senate on February 10, 1919, the women's suffrage law lost by one vote again. But in the 1918 election, more suffrage supporters were elected to Congress. The suffrage question came up again in the House on May 21, 1919. This time, it passed with 304 votes for and 89 against. The law then went to the Senate. It passed on June 4 by just two votes more than needed.

Carrie led the fight to get the 19th Amendment approved. This needed 36 state legislatures to agree. She told supporters not to let it be voted on in their state unless they were sure it would pass. But opponents introduced the bill in Southern states. Georgia, Alabama, Virginia, Maryland, South Carolina, Delaware, Florida, North Carolina, Louisiana, and Mississippi all voted it down. The governors of Connecticut and Vermont refused to call their lawmakers to vote. One more state loss, and the law would be defeated.

The final battle happened in Tennessee. Carrie was there to lead the campaign in Nashville in the hot summer of 1920. She wrote that there was a "force for evil" working against suffrage there. The vote was very close. The proposed law easily passed the Tennessee Senate. But in the House, after many delays, it passed by just one vote.

At her welcome home party in New York City, Carrie said: "Now that we have the vote let us remember we are no longer petitioners. We are not wards of the nation, but free and equal citizens." After much hard work by Carrie and NAWSA, the 19th Amendment was finally approved on August 26, 1920. This law gave 27 million women the right to vote. It was the biggest expansion of voting rights in American history.

Carrie retired from her national suffrage work after the 19th Amendment was approved. Before she retired, she started the League of Women Voters on February 14, 1920. This group was created to encourage women to use their new right to vote. In 1923, she published a book about the suffrage movement.

Global Women's Suffrage Movement

Carrie was also a leader in the global women's suffrage movement. She helped start the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) in 1902. This group eventually included organizations from 32 countries. She was its president from 1904 to 1923.

After George Catt died in 1905, Carrie spent many years promoting equal voting rights worldwide. Even after she retired from NAWSA, she kept helping women around the world. The IWSA is still active today, now called the International Alliance of Women.

Carrie first thought of an international women's suffrage group in 1900. By 1902, she decided to hold a meeting with women from many countries. The first IWSA meeting was in Berlin, Germany, with 33 people. Carrie was elected president. Mary Church Terrell, an African American suffragist, was one of the U.S. representatives. She spoke at the meeting in three languages.

Each international meeting was held in a different city. More people joined, and successes in women's rights were shared. The meeting in Budapest in 1913 was the largest ever. It had 500 representatives. The world's newspapers sent 230 reporters. And 2,800 visitors came to listen and learn.

From 1906 to 1913, Carrie worked on international suffrage. On one trip around the world from 1911 to 1912, Carrie spoke and helped start women's suffrage groups. She visited places like South Africa, Egypt, India, China, Japan, and Hawaii.

Because of World War I, the IWSA meetings stopped for some years. Three days after the war ended in 1918, Carrie planned to start the meetings again. The 1920 meeting was in Geneva. More than 400 women met, including people from Germany, France, Japan, China, India, and the United States. The group asked women from countries where they could vote to help women in countries where they could not.

The United States was asked to help in Jamaica, Cuba, and South America. South America was the only continent where no women could vote. In 1922, Carrie helped organize the Pan-American Association for the Advancement of Women. This group worked for women's education, equal rights for parents, and the right to vote.

The next year, Carrie traveled to Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, and Panama. She said, "I never did a piece of work which has so interested and stimulated my desires to help as this." In Peru in March 1923, Carrie started the National Council of Women in Action. This group worked for women's suffrage in Peru until they succeeded in 1956. Even though Carrie retired as IWSA president in 1923, she kept going to its meetings around the world.

Carrie and the League of Women Voters

Carrie Catt founded the League of Women Voters on February 14, 1920. This was six months before the 19th Amendment was approved. She started it during the annual meeting of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in Chicago. But she had talked about the group's purpose a year earlier in St. Louis.

In her speech on March 24, 1919, Carrie said: "Let us raise up a League of Women Voters... a League that shall be non-partisan and non-sectarian... and that shall be consecrated to three chief aims:

- To help women in every state in our own Republic get the right to vote. And to reach out across the seas to help women in every land.

- To remove unfair laws against women in states. This is so future women will not face these problems.

- To make our democracy safe for the Nation and the world. So every citizen feels secure and America is seen as a worthy leader."

In fall 1919, Carrie promoted the 19th Amendment. She also explained the purpose of the League of Women Voters on a "Wake Up America" tour. She spoke at 14 meetings in 13 western and Midwestern states in eight weeks. Her group also met with women and state leaders. By the time of NAWSA's "victory convention" in February 1920, 31 of the 36 needed states had approved the 19th Amendment. The 1920 meeting marked the end of NAWSA's main work and the start of the League of Women Voters.

At the 1920 meeting, Carrie honored the pioneers of the movement. This included past NAWSA presidents like Anna Howard Shaw and Susan B. Anthony. She praised their "hope" and "courage." She also wanted the meeting to "express the joy of the present." She asked what political parties wanted from women and what women wanted from parties.

In an inspiring speech, Carrie explained the League's plan. She said its goal was not to gain power. Instead, it was to "foster education in citizenship and to support legislation." Every woman was encouraged to register to vote and work within her chosen political party. But she stressed that the League "shall be allied with and support no party." Carrie said the League "must be nonpartisan and all partisan" in leading the way to educate for citizenship and pass laws.

At the 1920 meeting, the League's rules were approved. Carrie said she did not want to lead the new work. She felt it was for "younger and fresher women." Maud Wood Park was elected president of the League of Women Voters. Carrie accepted the title of "honorary chairman." The delegates also surprised Carrie with a special brooch. It had a large sapphire surrounded by diamonds. This was for her "distinguished service." Thousands of people, even schoolchildren, gave small amounts of money for this gift.

Besides the national League, women's suffrage groups in states also became state leagues of women voters in 1920. In 2020, the League of Women Voters has a national group and over 700 state and local groups. They are in all 50 states and other places. The League works to register new voters. They also hold community discussions and debates. They give voters the information they need for elections. They work on laws at local and state levels.

Role During the World Wars

Carrie Catt was active in groups that worked for peace in the 1920s and 1930s. When World War I started in 1915, some women in the United States wanted to form a group to help end the war. On January 10, 1915, over 3,000 women met in Washington, DC. Carrie and Jane Addams called this meeting. They formed the Women's Peace Party. Jane Addams was chosen as chairman, and Carrie as honorary chairman.

On February 25, 1917, NAWSA, with Carrie as president, offered women's help to the U.S. government. They pledged the support of their over two million members if needed. NAWSA made it clear that their work for suffrage would continue. On April 2, 1917, President Wilson asked Congress to declare war. Carrie's decision to support the war led to her leaving the Women's Peace Party. This also caused some bad feelings between her and the peace activists.

After the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was approved, Carrie returned to the peace movement. She did not want to join any existing group. So, Carrie and leaders from nine national women's groups started their own. It was called the National Committee on the Cause and Cure of War (NCCCW). The group first met in spring 1924. They chose Carrie to be their leader.

The group divided the reasons for war into four types: psychological, economic, political, and social. They believed it was women's job to end wars. They saw women as morally brave.

The NCCCW held its first meeting in Washington, DC, in January 1925. There were 450 people there. Eleanor Roosevelt attended. Carrie told the group that white races would eventually have to share their wealth. She said, "We stole land—whole continents... We must leave the door open... in order that justice can be done to all the races on all the continents."

In 1932, Carrie resigned as head of the NCCCW. But she kept going to meetings, giving speeches, and supporting peace. However, she saw that another war would soon start. By 1941, when it was clear the U.S. would enter World War II, the NCCCW broke apart. In spring 1943, the NCCCW was officially closed. A new group, the Women’s Action Committee for Victory and Lasting Peace, took its place. This new group supported the idea of the United Nations.

In 1933, when Adolf Hitler came to power, Carrie organized a group. It was called the Protest Committee of Non-Jewish Women Against the Persecution of Jews in Germany. In August 1933, the group sent a letter of protest to Hitler. It was signed by 9,000 non-Jewish American women. It spoke out against violence and unfair laws against German Jews. Carrie pushed the U.S. government to make immigration laws easier. This would help Jews find safety in America. For her work, she received the American Hebrew Medal. In 1938, Carrie helped start a group to protest anti-Jewish acts in the U.S.

Women's rights leaders abroad knew about her reputation. In 1938, she was asked to sign a paper to help Hungarian feminists Eugénia Miskolczy Meller and Sarolta Steinberger move to the USA. Carrie had given money to a fund that supported the Hungarian Feminist Association. She declined the request, saying she was old and had taken on many responsibilities.

The last event she helped organize was the Women's Centennial Congress in New York in 1940. This celebrated the feminist movement in the United States.

Carrie's Views on Race

Carrie Catt's ideas about race and immigration changed over her long life. Early in her career, she sometimes showed feelings against immigrants. In the 1880s, she gave speeches like "America for Americans." These speeches reflected common anti-immigrant feelings of the time.

In the 1890s, before she became president of NAWSA, Carrie gave speeches. She talked about the "ignorant foreign vote." She also mentioned Native American men not knowing about government. Later, Carrie said that the votes of men who could not read in the South could be "bought."

In these speeches, Carrie blamed political corruption or lack of education for these groups' voting problems. Her solutions were education and reform, not taking away their right to vote. Even when she spoke against the "ignorant foreign vote," Carrie also mentioned "citizens of foreign birth who desire good government." She said their lives were threatened by political machines.

One historian noted that Carrie's early views might seem unfair today. But they were popular at the time. Women were frustrated that immigrant men could vote after only six months, while women could not. Carrie dreamed of a country where all voters, men and women, were educated. Her doubts about immigrants began to fade when she started working internationally.

During the final weeks of the vote in Tennessee, opponents falsely accused Carrie of supporting mixed-race marriage. This was illegal in Tennessee and many other states. Carrie denied saying this. She said mixed-race marriage was "an absolute crime against nature." A historian, Elaine Weiss, said Carrie was right that this topic was dangerous. The accusation was a lie made up by opponents.

Carrie also used an argument from 1867 to counter claims that women's suffrage would hurt white power in the South. She said that "white supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened by women's suffrage." She used census data to argue that white voters (men and women) would outnumber Black voters in most Southern states. However, Carrie also said this argument was "ridiculous." She stated that "all people must be included."

In September 1917, the NAWSA Board, led by Carrie, passed a resolution. It said they believed in "broad American democracy." This democracy "knows no bias on the ground of race, color, creed or sex." It aimed for all Americans to be united, not divided by their backgrounds. In November 1917, Carrie called for suffrage for all women in the NAACP’s newsletter. She said, "the struggle for woman suffrage is not white woman's struggle but every woman's struggle." She added, "there will never be a true democracy until every responsible and law-abiding adult in it, without regard to race, sex, color or creed has his or her own inalienable and unpurchasable voice in the government."

As NAWSA President, Carrie did not want to change the 19th Amendment. She opposed adding the word "white" to it. She also opposed another idea that would let states decide on suffrage laws themselves. In May 1919, Carrie wrote to the NAACP and two African American suffragists. She assured them that NAWSA was against any effort to limit voting to white women only.

In her later years, Carrie changed her earlier views against immigrants. She called herself "a regular jingoist" (someone who is too nationalistic) for her past ideas. In 1909, she said her group's task would not be done until women worldwide were free from unfair laws. In 1918, NAWSA pushed Congress to let women in Hawaii vote, including Native Hawaiian women. In 1924, Carrie spoke out against the Ku Klux Klan for their racism.

Also, NAWSA and its earlier groups included people of all races. African American suffragists were key helpers in Carrie's campaign in New York. Carrie's Woman Suffrage Party in New York actively sought immigrant support. They printed pro-suffrage materials in 26 languages. They held rallies in immigrant neighborhoods. In 1919, Carrie supported a group in New York City that asked Congress to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment gave Black men the right to vote. At the founding of the League of Women Voters, Carrie asked the new group to "remove the remaining legal discriminations against women."

In 1920, a newspaper reported on a meeting of the "Woman Voter's League." A speaker there said Carrie Catt had appealed to Southern women to help Black women get the right to vote. Another anti-suffrage leader, Josephine A. Pearson, criticized Carrie after Tennessee approved the 19th Amendment. She said Carrie was seen "marching through the streets of New York, with a negro woman on either side of her!"

Carrie became more open about her opposition to discrimination in the 1920s–1940s. She protested a hotel's policy in Washington, D.C. that excluded African Americans. This prevented them from attending a NCCCW meeting. She also spoke out about Jewish refugees escaping Nazi Germany in the 1930s.

Death and Legacy

On March 9, 1947, Carrie Catt died of a heart attack at her home in New Rochelle, New York. She was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City. She was buried next to her longtime companion, Mary Garrett Hay, who was also a suffragist. Mary Church Terrell, an African American suffragist, sent a message remembering Carrie. She said, "The whole world has lost a great, good, and gifted woman." At her funeral, a minister praised her for bringing "dignity and prestige" to women in America and around the world.

Honors and Recognition

Carrie Catt received many awards and honors during her life and after her death. In 1921, she was the first woman to get an honorary doctorate degree from the University of Wyoming. In 1923, the League of Women Voters named her one of the "12 Greatest Living American Women." In 1925, she received another honorary law degree from Smith College.

In 1926, she was on the cover of Time magazine. In 1930, she won an award for her international peace work. In 1933, she received the American Hebrew Medal. In 1935, the Turkish government put her on a stamp to honor her work. In 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt honored her at the White House for her peace activism. In 1940, she received more honorary degrees and awards. In 1941, she received the Chi Omega award from her friend Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House.

After her death, a stamp was issued in 1948 remembering the Seneca Falls Convention. It featured Carrie Catt, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott. In 1975, Carrie was the first person inducted into the Iowa Women's Hall of Fame. In 1982, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. In 1992, she was named one of the ten most important women of the century by an Iowa group. In 2013, she was honored on the Women of Achievement Bridge in Des Moines, Iowa.

On August 26, 2016 (Women's Equality Day), a statue was revealed in Nashville, Tennessee. It shows Carrie Catt and other suffragists. In 2020, she was named a "Valiant Woman of the Vote." Carrie is one of three suffragists honored with a statue at the Turning Point Suffrage Memorial in Virginia.

The League of Women Voters often honors Carrie as its founder. In 1929, the League placed bronze plaques honoring her work across the country. In 1947, the national League started the Carrie Chapman Catt Memorial Fund. This fund promoted suffrage abroad, voter education, and good citizenship. Many local Leagues of Women Voters also give out Carrie Chapman Catt Awards. In 2019, the Iowa Secretary of State started the Carrie Chapman Catt Award. It goes to Iowa high schools that register at least 90 percent of their eligible students to vote.

Carrie's childhood home in Charles City, Iowa, has been restored. It is now a museum about her life and the women's suffrage movement. In 2020, it was added to the National Women's Suffrage Trail.

Women's Voting Rights

As president of the largest women's suffrage group, women's voting rights are a big part of Carrie's legacy. The 19th Amendment gave about 27 million American women the right to vote. This included women of all races who were not prevented from voting for other reasons. It was the largest single expansion of voting rights in American history. This included three million African American women of voting age. About 500,000 of them lived outside the Deep South. By 1960, over two million African American women in these states could vote.

Also, some African American women in the South were able to register and vote in 1920. One historian said that Black women's participation was enough to make a Georgia lawmaker predict that the 19th Amendment would end white supremacy in Georgia. In South Carolina, Black women surprised white registrars. Many Black women registered, and the only unfair treatment was that white people were registered first.

The 19th Amendment did not stop all unfair treatment against women voters. For example, no women could vote in Georgia or Mississippi in 1920. This was because state lawmakers were not called to pass the needed laws. Also, by the end of the 1920s, African American women in the South were again prevented from voting by unfair laws. Puerto Rican women did not get full voting rights until 1935. Native American women who did not give up their tribal citizenship could not vote in 1920. Chinese American women could not vote because of the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law stopped Chinese Americans from becoming citizens until 1943. Women of color, especially African American women, faced unfair treatment until the Twenty-fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution (which stopped poll taxes) and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed in the 1960s.

Women's voter turnout was about 38 percent in 1920. Men's turnout was over 65 percent. Women's voting rates slowly increased over time. Women became the majority of voters in 1968. They started voting at higher rates than men in 1980. By 2016, women's voter turnout was 63 percent, compared to 53 percent for men. This was a difference of 10 million voters. Also, since 1980, men and women's voting choices started to differ. Women were more likely to vote for Democratic candidates. This difference is now a lasting part of American politics.

At Iowa State University

In 1921, Carrie Catt was the first woman to give a graduation speech at Iowa State University. She also received an honorary law degree there. She was invited to speak again in 1930. In 1933, she received an award for her distinguished service.

When George Catt died in 1905, he left money to Iowa State in his will. But lawyers said the donation was not allowed under New York law. So, Carrie gave $100,000 in bonds to the University. This was to honor George Catt's wishes. The George W. Catt Endowment still gives scholarships to students each year. A few years after her husband's death, Carrie donated more money to Iowa State. In 1926, she donated money to her sorority. She also left her personal library of over 1,000 books to the University.

In 1990, Iowa State University announced it was renaming the Old Botany Building as Carrie Chapman Catt Hall. The building was dedicated in 1995 after a big renovation. In 1992, Iowa State University started the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics. This center studies women in politics and encourages people to be involved in their community.

Carrie's past words about race and white supremacy caused controversy at Iowa State in 1995. A student publication said Carrie Chapman Catt was a racist. This led to a student movement that asked for changes, including renaming Catt Hall.

The student article used a book that compared the racial ideas of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Anna Howard Shaw, and Carrie Catt. The book said these women were honest and truly wanted rights for all women. But it also said they used racist ideas to their advantage in a racist society.

In September 1997, a student started a hunger strike. He had several demands, including renaming Catt Hall. The controversy calmed down for a while after 1998. A study group could not agree on whether to rename the building.

The controversy started again in 2016–2017. A letter called for stopping the celebration of a "White Supremacist." The movement gained strength as the university had several racist incidents. Also, the country had a national discussion about race after George Floyd's death. In July 2020, Iowa State President Wendy Wintersteen announced a committee. This committee would create a plan for renaming buildings on campus. In March 2021, the University announced the members of a new committee. This committee will consider requests to rename buildings, including Catt Hall.

19th Amendment Centennial

2020 marked 100 years since the League of Women Voters was founded and the 19th Amendment was approved. The League is a respected, nonpartisan group. It continues to educate citizens on important issues. It also works to expand voting access for all U.S. citizens.

As part of the 19th Amendment's 100th anniversary in 2020, Carrie Catt was featured in many places. She was in newspaper and magazine articles. She was in recent books, like Elaine Weiss’s The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote. This book is being made into a film. Carrie was also in a PBS documentary called The Vote and an Iowa PBS documentary.

Personal Life

In March 1883, Carrie Lane became superintendent of schools in Mason City, Iowa. Leo Chapman bought and started publishing the weekly Mason City Republican newspaper. He supported women's suffrage. He and Carrie became engaged and married on February 12, 1885. They both worked as editors for the newspaper. In May 1886, Leo sold the newspaper and went to San Francisco to find work. Carrie stayed in Iowa with her parents. In August 1886, Carrie got a telegram that Leo was very sick. By the time she arrived in San Francisco, he had died.

While in San Francisco, she met George Catt by chance. They had been in college together. He was about to become a chief engineer for a bridge-building company. In August 1887, Carrie moved back to Iowa, but they stayed in touch. In spring 1890, Carrie traveled to Seattle, Washington, where George now lived. They married on June 10, 1890.

Their marriage was filled with deep love and respect. Carrie said they made a team to work for the cause. Her husband said he would earn enough money for both of them. This would free her to work for reform for two people. They both traveled a lot for their work. But they also found time to travel together. On October 8, 1905, George Catt died at age 45. He was a successful engineer. His money left Carrie financially independent for the rest of her life.

Carrie Catt lived at Juniper Ledge in Briarcliff Manor, New York from 1919 to 1928. Then she moved to nearby New Rochelle, New York. After George Catt's death, Carrie lived with Mary Garrett Hay, a suffrage leader from New York. Carrie asked to be buried next to Mary, not her first husband. Her second husband's body was donated to science, as he wished. When Mary died in 1928, Alda Heaton Wilson moved in with Carrie. She stayed as Carrie's secretary until Carrie's death. Alda was Carrie's companion and later handled her estate.

See also

In Spanish: Carrie Chapman Catt para niños

In Spanish: Carrie Chapman Catt para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |