Voting Rights Act of 1965 facts for kids

|

|

| Long title | An Act to enforce the fifteenth amendment of the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | VRA |

| Nicknames | Voting Rights Act |

| Enacted by | the 89th United States Congress |

| Effective | August 7, 1965 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 89-110 |

| Statutes at Large | 79 Stat. 437 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | Title 52—Voting and Elections |

| U.S.C. sections created |

|

| Legislative history | |

|

|

| Major amendments | |

|

|

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

|

List

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966)

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966) Cardona v. Power, 384 U.S. 672 (1966) Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969) Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969) Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970) City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975) East Carroll Parish Sch. Bd. v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976) Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976) United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980) Escambia County v. McMillan, 466 U.S. 48 (1984) Mississippi Republican Executive Committee v. Brooks, 469 U.S. 1002 (1984) NAACP v. Hampton County Election Comm'n, 470 U.S. 166 (1985) Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) Clark v. Roemer, 500 U.S. 646 (1991) Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380 (1991) Houston Lawyers' Association v. Attorney General of Texas, 501 U.S. 419 (1991) Presley v. Etowah County Comm'n, 502 U.S. 491 (1992) Growe v. Emison, 507 U.S. 25 (1993) Voinovich v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146 (1993) Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) Holder v. Hall, 512 U.S. 874 (1994) Johnson v. De Grandy, 512 U.S. 997 (1994) Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995) Morse v. Republican Party of Virginia, 517 U.S. 186 (1996) Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996) Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952 (1996) Lopez v. Monterey County, 519 U.S. 9 (1996) Young v. Fordice, 520 U.S. 273 (1997) Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board, 520 U.S. 471 (1997) Abrams v. Johnson, 521 U.S. 74 (1997) Foreman v. Dallas County, 521 U.S. 979 (1997) City of Monroe v. United States, 522 U.S. 34 (1997) Texas v. United States, 523 U.S. 296 (1998) Lopez v. Monterey County, 525 U.S. 266 (1999) Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board, 528 U.S. 320 (2000) Branch v. Smith, 538 U.S. 254 (2003) Georgia v. Ashcroft, 539 U.S. 461 (2003) League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006) Riley v. Kennedy, 553 U.S. 406 (2008) Bartlett v. Strickland, 556 U.S. 1 (2009) Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder, 557 U.S. 193 (2009) Perry v. Perez, 565 U.S. 388 (2012) Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S. 529 (2013) Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, No. 13-895, 575 U.S. ___ (2015) Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Bd. of Elections, No. 15-680, 580 U.S. ___ (2017) Cooper v. Harris, No. 15-1262, 581 U.S. ___ (2017) North Carolina v. Covington, No. 16-1023, 581 U.S. ___ (2017) |

|

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) is a very important U.S. federal law. It stops racial discrimination in voting. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed it into law on August 6, 1965. This happened during the peak of the civil rights movement.

Congress later updated the Act five times to make its protections even stronger. The Act was created to make sure everyone could vote. This right is protected by the 14th and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution. It especially helped racial minorities in the South. The U.S. Department of Justice says it's the most effective federal civil rights law ever.

The Act has many rules for elections. Its "general provisions" protect voting rights across the whole country. Section 2 stops state and local governments from making voting rules that prevent citizens from voting because of their race, color, or language group. Other rules specifically banned literacy tests. These tests were used to stop racial minorities from voting.

The Act also had "special provisions" for certain areas. Section 5 required these areas to get federal approval before changing voting rules. This was to ensure the changes did not discriminate. Another special rule made sure areas with many language minorities offered bilingual ballots.

The special rules applied to areas that had a history of unfair voting practices. In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the way these areas were chosen was outdated. This ruling, Shelby County v. Holder, made Section 5 hard to use. After this, many areas increased how often they removed voters from registration lists.

In 2021, the Supreme Court changed how Section 2 of the Act was understood. This ruling, Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, made Section 2 weaker. It said that some voting rules that affect minority groups more might still be allowed. This could happen even if there was no proof of election fraud.

Studies show the Act greatly increased voter turnout and registration. This was especially true for Black people. It also led to better public services, like education, in areas with more Black residents. More members of Congress started supporting civil rights laws. Also, more Black people were elected to local offices.

Contents

Why the Act Was Needed

The United States Constitution first let each state decide who could vote. After the Civil War, three new amendments were added. These were the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. The 15th Amendment, added in 1870, said that voting rights could not be denied based on race or color.

Congress passed laws in the 1870s to enforce these amendments. But after 1877, these laws were not strongly enforced. Southern states then created Jim Crow laws to stop racial minorities from voting. These laws included literacy tests, poll taxes, and other unfair rules. Very few African Americans could register or vote. They also faced threats and violence.

In the 1950s, the Civil Rights Movement grew stronger. People demanded that the federal government protect voting rights. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the Civil Rights Act of 1960. These laws tried to help, but they were not enough. It was very hard for the Justice Department to win lawsuits against states. States would just create new unfair rules.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 also included some voting protections. But it did not stop most forms of voting discrimination. President Johnson knew more was needed. He asked his Attorney General to write a very strong voting rights law.

The Push for the Act

After the 1964 elections, civil rights groups pushed for federal action. Groups like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) led protests. These protests were especially strong in Selma, where police violently stopped Black people from registering to vote.

Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders organized peaceful marches in Selma in early 1965. Police and white counter-protesters attacked them. News coverage of these events shocked the nation. On February 18, a young Black protester named Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot and killed by a state trooper. He was unarmed and protecting his mother.

This event led to the first Selma to Montgomery marches. On March 7, marchers were stopped by police at the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Police used tear gas and attacked them. This day became known as ""Bloody Sunday"." Televised images of the violence caused outrage across the country.

A second march happened on March 9. That evening, three white ministers who joined the march were attacked. Reverend James Reeb from Boston died from his injuries.

These events convinced President Johnson to act quickly. On March 15, he spoke to Congress. He urged them to pass a strong voting rights law. He even used the civil rights rallying cry, "we shall overcome." The Voting Rights Act was introduced in Congress two days later.

How the Act Became Law

Previous laws had failed to stop states from blocking Black voters. Congress realized a new, strong federal law was needed. The Supreme Court later agreed. It said that Congress had the power to pass the Act to enforce the 15th Amendment.

Creating the Original Bill

The Voting Rights Act was introduced in Congress on March 17, 1965. It was supported by leaders from both major parties. President Johnson wanted Republican support to pass the bill.

The bill had special rules for certain states and local governments. It included a "coverage formula" to identify areas with a history of discrimination. These "covered jurisdictions" had to get "preclearance" (approval) from the federal government before changing voting rules. This was to ensure changes were not discriminatory. The bill also banned literacy tests in these areas. It allowed federal officials to register voters and watch elections. These special rules were set to end after five years.

The coverage formula applied to areas that used voting tests in 1964. Also, less than 50% of their voting-age residents were registered or voted in the 1964 election. This mainly affected states in the Deep South. The bill also included a general ban on racial discrimination in voting for the whole country.

The bill faced debates in Congress. Some senators from Southern states opposed it. They tried to stop it or weaken it. For example, there was a debate about banning poll taxes in state elections. Eventually, the Senate passed the bill on May 26, 1965, by a vote of 77 to 19.

The bill then went to the House of Representatives. It also faced opposition there. An alternative bill was proposed, but it failed. On July 9, the House passed the Voting Rights Act by a vote of 333 to 85.

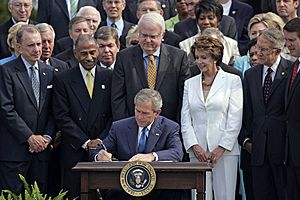

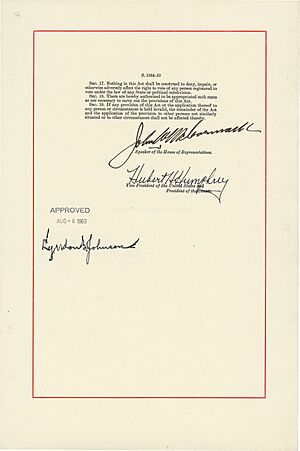

Since the House and Senate versions were slightly different, a special committee worked out the final details. They agreed on a compromise regarding poll taxes. On August 6, 1965, President Johnson signed the Act into law. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and John Lewis were there for the signing.

Changes to the Act Over Time

Congress has updated the Act many times since 1965. Major changes happened in 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992, and 2006. Each time, the special rules were about to expire. Congress kept extending them because voting discrimination continued.

In 1975, Congress expanded the Act to protect language minorities. This included American Indians, Asian Americans, Alaskan Natives, and people of Spanish heritage. It required election materials to be provided in multiple languages in certain areas.

Some changes were made because Congress disagreed with Supreme Court rulings. For example, in 1982, Congress changed Section 2. It made it illegal for voting practices to have a discriminatory effect, even if there was no intent to discriminate. This was to overturn a Supreme Court decision that said only purposeful discrimination was banned.

In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the "coverage formula" in Shelby County v. Holder. This formula decided which areas needed federal approval for voting changes. The Court said the formula was outdated. This made the Section 5 preclearance rule unenforceable without a new formula from Congress. Since then, several bills have been proposed to create a new formula, but none have passed.

What the Act Does

The Act has two main types of rules: "general provisions" that apply everywhere, and "special provisions" that applied to certain states and local governments.

General Protections for Voters

Section 2 of the Act stops any area from having voting rules that prevent people from voting because of their race, color, or language. This means rules cannot be used to intentionally discriminate. Also, rules cannot have a discriminatory effect, even if discrimination wasn't the goal.

The Act also bans specific actions that interfere with voting. Section 201 bans literacy tests and similar requirements nationwide. These were once used to stop minorities from voting. Section 202 stops areas from requiring people to live there for more than 30 days to vote in a presidential election.

Section 11 makes it illegal for anyone to stop a qualified person from voting or counting their ballot. It also bans intimidating or harassing people for voting. It has rules against voter fraud, like submitting false registration forms or voting twice.

Section 208 says that if someone cannot read English or has a disability, they can bring someone to help them vote. This helper cannot be their employer or union agent.

Special Protections (Before 2013)

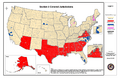

The "coverage formula" in Section 4(b) identified areas with a history of discrimination. These areas had to follow special rules. This included states like Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia.

Preclearance Rule

Section 5 required these "covered jurisdictions" to get federal approval, called "preclearance," before changing any voting laws. They had to prove the change would not discriminate. If they couldn't prove it, the change was not allowed. This rule was meant to stop new discriminatory practices from being put in place.

Areas could get preclearance from the U.S. attorney general or the U.S. District Court for D.C.. The attorney general had 60 days to object to a proposed change. If they objected, the change could not happen.

The Supreme Court said that Section 5 was meant to stop "retrogression." This means it stopped changes that would make discrimination worse than before. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that the coverage formula was unconstitutional. This meant Section 5 could no longer be enforced unless Congress created a new formula.

Federal Help for Voters

The Act also allowed for "federal examiners" and "federal observers." Federal examiners could register voters and manage voter lists in areas with severe discrimination. This helped prevent local officials from unfairly stopping people from registering. This part of the Act was repealed in 2006.

Federal observers could watch elections at polling places. Their job was to make sure elections were fair. They watched for any discriminatory actions, like officials denying qualified voters or intimidating people. They also documented problems for future lawsuits.

Bilingual Election Materials

Sections 4(f)(4) and 203(c) required certain areas to provide election materials in multiple languages. This included voter registration forms, ballots, and instructions. This was for areas with many people from a single language minority group who might not speak English well. This helped break down language barriers and fight discrimination.

Impact of the Act

The Voting Rights Act had a huge and immediate impact. By the end of 1965, nearly 250,000 new Black voters had registered. Many were registered by federal examiners. By 1967, over half of African Americans in covered areas were registered to vote.

The number of Black elected officials also grew greatly. Between 1965 and 1985, the number of Black state lawmakers in the former Confederate states jumped from 3 to 176. Nationwide, Black elected officials increased from 1,469 in 1970 to about 10,500 by 2011.

Registration rates for language minority groups also increased after 1975. The percentage of Hispanic voters nearly doubled by 2006. Asian American voter registration also saw a big increase.

The Act also changed American politics. It helped shift the Democratic and Republican parties. As more Black voters joined the Democratic Party, Southern white conservatives began to support the Republican Party. This made the two parties more different in their beliefs. It also led to more competition in Southern elections.

Studies show the Act successfully increased voter turnout, especially for African Americans. It also led to more public services in areas with larger Black populations. Members of Congress from areas covered by the Act were more likely to support civil rights laws. Research also found that the Act helped reduce political violence.

After the Supreme Court's 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder, some areas that were no longer covered increased how often they removed voters from registration lists. This shows the importance of the Act's protections.

Court Decisions on the Act

The Supreme Court quickly reviewed the Act's constitutionality. In 1966, in South Carolina v. Katzenbach, the Court said the Act was a constitutional way to enforce the 15th Amendment. It agreed that the widespread discrimination justified the strong preclearance rule.

The Court also upheld the ban on literacy tests. It said Congress could pass laws to protect voting rights, even if the actions weren't always unconstitutional on their own.

The constitutionality of Section 2, which bans voting practices with a discriminatory effect, has been debated. The 14th and 15th Amendments usually only ban intentional discrimination. However, lower courts have consistently upheld Section 2 as constitutional.

The Supreme Court upheld the Section 5 preclearance rule multiple times before 2013. It said the rule was needed because discrimination continued. But in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the Court struck down the coverage formula. It said the formula was outdated and violated the idea of equal treatment for all states. This made Section 5 unenforceable.

The Act also deals with "racial gerrymandering." This is when election districts are drawn in a way that unfairly favors or disadvantages a racial group. The Supreme Court has said that while the Act protects minority votes, districts cannot be drawn primarily based on race. If race is the main factor, the district plan must meet very strict legal tests to be allowed.

Recently, in 2023, a court questioned whether private groups like the NAACP could sue under Section 2 of the Act. This ruling, if upheld, could make it harder to challenge unfair voting maps.

Images for kids

-

Final page of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson, President of the Senate Hubert Humphrey, and Speaker of the House John McCormack.

-

States and counties encompassed by the Act's coverage formula in January 2008 (excluding bailed-out jurisdictions). Several counties subsequently bailed out, but the majority of the map accurately depicts covered jurisdictions before the Supreme Court's decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which declared the coverage formula unconstitutional.

See also

In Spanish: Ley de derecho de voto de 1965 para niños

In Spanish: Ley de derecho de voto de 1965 para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |