Civil Rights Movement facts for kids

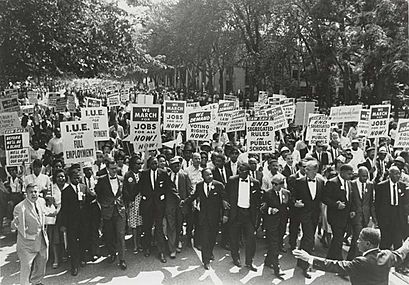

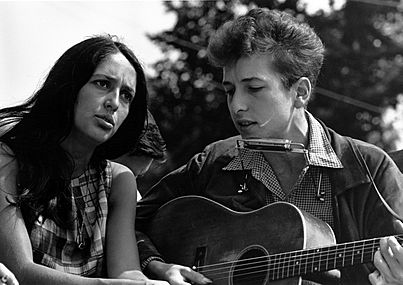

Protesters at the March on Washington in 1963

|

|

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Date | 1954–1968 (15 years) |

| Location | United States (especially the South) |

| Causes | Racial discrimination; segregation; racism |

| Methods | Non-violent protests; civil disobedience; lawsuits |

| Results | |

| Successes |

|

The African-American Civil Rights Movement was a series of important events in the United States. Its main goal was to get equal rights for African-American people. At the time, people usually called it The Civil Rights Movement. This article focuses on the part of the movement that happened between 1954 and 1968.

The movement is well-known for using peaceful protests. People also used civil disobedience, which means peacefully refusing to follow unfair laws. Activists of all races took part in actions like boycotts, sit-ins, and protest marches.

Many different people and groups were part of the Civil Rights Movement. Not everyone agreed on everything. For example, the Black Power movement believed black people should demand their civil rights. They thought black people might need to use force to get white leaders to give them those rights.

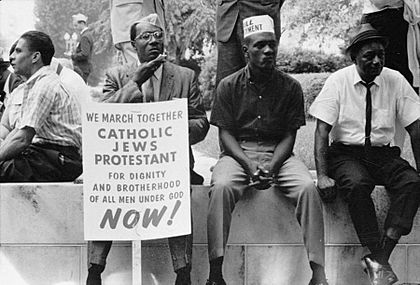

People of different races and religions joined the Civil Rights Movement. Most of the leaders and activists were African-American. But the movement also got support from labor unions, religious groups, and some white politicians. One of these was President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The Civil Rights Movement helped pass five federal laws. It also helped add two amendments to the U.S. Constitution. These laws officially protected the rights of African Americans. The movement also helped change how many white people thought about the way black people were treated. It changed their ideas about the rights black people deserved.

Contents

- Life Before the Civil Rights Movement

- Key Moments in the Civil Rights Movement

- Brown v. Board of Education (1954): Ending School Segregation

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956): Standing Up for Rights

- Integrating Little Rock Central High School (1957): Federal Power Steps In

- Sit-ins (1958-1960): Peaceful Protests at Lunch Counters

- Freedom Rides (1961): Challenging Segregation on Buses

- Voter Registration (1961-1965): The Fight to Vote

- Integrating Mississippi Universities (1956-1965): Breaking Down Barriers

- Birmingham Campaign (1963): Children Join the Fight

- "Rising Tide of Unhappiness" (1963): Protests Spread

- The March on Washington (1963): A Dream for Equality

- Malcolm X Joins the Movement (1964): A New Voice

- Mississippi Freedom Summer (1964): A Summer of Change

- Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Major Victory

- King Awarded Nobel Peace Prize (1964): Global Recognition

- Selma to Montgomery Marches (1965): Marching for Voting Rights

- The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Making Voting Fair

- Fair Housing Movements (1966-1968): Equal Homes for All

- The King Assassination and the Poor People's Campaign (1968): A Legacy of Hope

- Deaths During the Movement

- Quick Facts About the Civil Rights Movement

- Related Topics

- Images for kids

- See also

Life Before the Civil Rights Movement

Before the American Civil War, nearly four million black people were slaves in the United States. Only white men who owned property could vote. Also, only white people could be United States citizens.

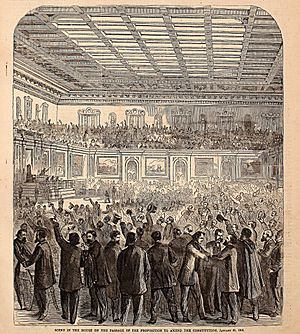

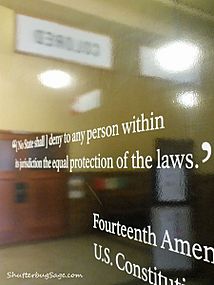

After the Civil War, the U.S. government passed three important changes to the Constitution:

- The 13th Amendment (1865) ended slavery.

- The 14th Amendment (1868) made African Americans citizens.

- The 15th Amendment (1870) gave African American men the right to vote. (At that time, no women in the U.S. could vote).

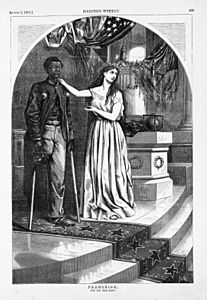

Laws in the Southern States

After the Civil War, the U.S. government tried to protect the rights of former slaves in the South. This time was called Reconstruction. But Reconstruction ended in 1877. By the 1890s, only white people were in charge of the Southern states' legislatures. Southern Democrats did not support civil rights for black people. They had full control of the South. This gave them a lot of power in the United States Congress.

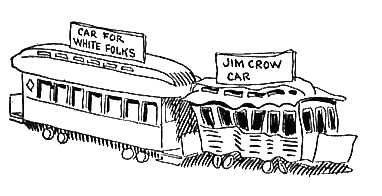

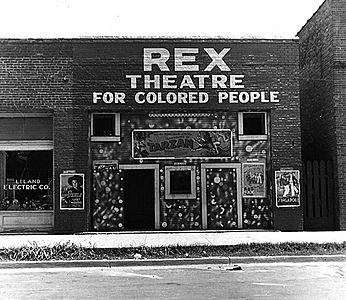

Starting in 1890, Southern Democrats began to pass state laws. These laws took away the rights African Americans had gained. These unfair laws were called Jim Crow laws. For example, they included:

- Laws that made it impossible for black people to vote. This is called disenfranchisement. Since they could not vote, black people also could not be on juries.

- Laws that required racial segregation. This meant black people and white people were separated. For example, black people could not:

- Go to the same schools, restaurants, or hospitals as white people.

- Use the same bathrooms or drink from the same water fountains.

- Sit in front of white people on buses.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court said these laws were legal. This happened in a case called Plessy v. Ferguson. The Court said that having things be "separate but equal" was okay. In the South, everything was separate. But places for black people, like schools and libraries, got much less money. They were not as good as places for white people. Things were separate, but they were not equal.

Violence against black people also increased. Individuals, groups, and large crowds could hurt or even kill African Americans. The government did not try to stop them or punish them.

Problems Across the United States

The problems were worst in the South. But unfair treatment also affected African Americans in other parts of the country.

Segregation in housing was a problem everywhere in the United States. Many African Americans could not get mortgages to buy houses. Some realtors would not sell black people houses in the suburbs where white people lived. They also would not rent apartments in white areas. The federal government did nothing about this until the 1950s.

When he became president in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson made government offices segregated. He believed that segregation was best for everyone.

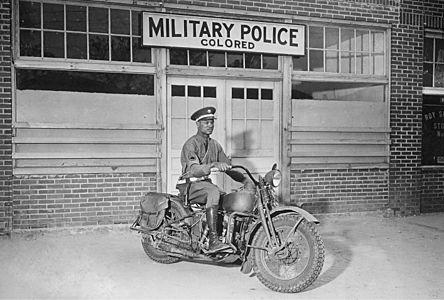

Black people fought in both World War I and World War II. But the military was segregated. Black soldiers were not given the same chances as white soldiers. After black veterans spoke out, President Harry S. Truman ended segregation in the military in 1948.

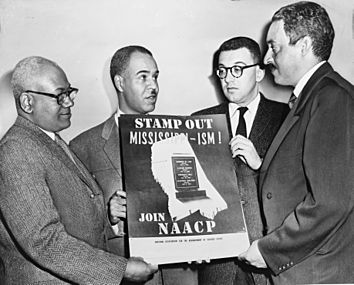

Early Efforts for Change

African Americans tried to fight back against discrimination in many ways. They formed new groups and tried to create labor unions. They tried to use the courts to get justice. For example, in 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was started. It worked to end race discrimination through lawsuits, education, and speaking to politicians.

But many African Americans became frustrated. They did not like the idea of using slow, legal ways to end segregation. Instead, African American activists decided to use protests, nonviolence, and civil disobedience. This is how the African-American Civil Rights Movement of 1954-1968 began.

Pictures from Before the Movement

-

1865 Cartoon about how black people served in the Civil War and should be able to vote.

-

A separate movie theater for black people in Mississippi (1937).

-

A black man drinks from a "colored" drinking fountain in Oklahoma City (1939).

-

Segregation also happened in the North. This sign is from Detroit (1942).

Key Moments in the Civil Rights Movement

Brown v. Board of Education (1954): Ending School Segregation

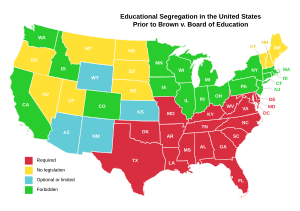

Schools in the South, and some other parts of the country, had been segregated since 1896. In that year, the Supreme Court had ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that segregation was legal. They said this was true as long as things were "separate but equal."

In 1951, thirteen black parents filed a class action lawsuit. They sued the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas. The parents argued that the black and white schools were not "separate but equal." They said the black school was much worse than the white one.

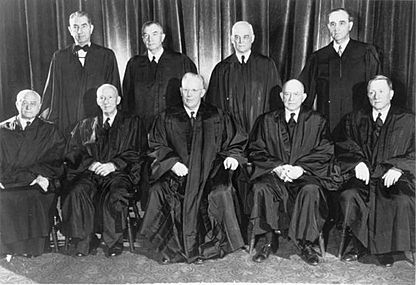

The lawsuit eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court. After years of work, Thurgood Marshall and other NAACP lawyers won the case. The Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were illegal. All nine Supreme Court judges agreed.

In their decision, the Court said:

We conclude that, in ... public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.

This was the Civil Rights Movement's first big win. However, Brown did not change Plessy v. Ferguson completely. Brown made segregation in schools illegal. But segregation in other places was still legal.

-

Members of the NAACP, including Thurgood Marshall (right), won Brown.

-

The all-white Supreme Court that ruled against school segregation.

-

Door at the Brown museum. It shows the "Colored" and "White" signs of segregation.

-

Black and white students together after Brown in Washington, D.C..

-

U.S. Marshals protect 6-year-old Ruby Bridges. She was the only black child in a Louisiana school.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956): Standing Up for Rights

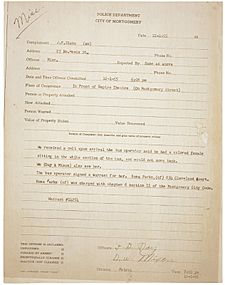

On December 1, 1955, local black leader Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a public bus. She did this to make room for a white passenger. Black people were not allowed to sit in front of white people on the bus. If a white person got on and there were no seats, a black person was expected to give up their seat. Parks was a civil rights activist and NAACP member. She had just learned about nonviolent civil disobedience. She was arrested.

Because of this, African Americans gathered and organized the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The boycott lasted for 381 days. It almost made the bus system go bankrupt. Meanwhile, the NAACP had been working on a lawsuit about segregation on buses. In 1956, they won the case. The Supreme Court ordered Alabama to end segregation on its buses. The boycott ended with a victory.

-

Rosa Parks being fingerprinted after her arrest.

Integrating Little Rock Central High School (1957): Federal Power Steps In

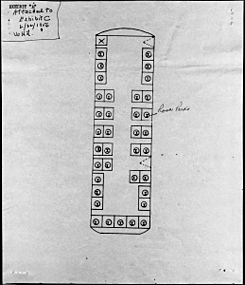

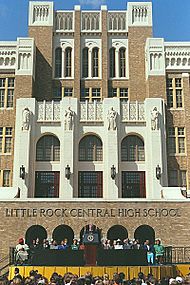

In 1957, the NAACP chose nine African American students. They were called the "Little Rock Nine". These students were to attend Little Rock Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Before this, only white students were allowed at the school. But the Little Rock School Board had agreed to follow the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education. They would end segregation in their schools.

Then came the black students' first day of school. The Governor of Arkansas called out soldiers from the Arkansas National Guard. He wanted to stop the black students from entering the school. This was against a Supreme Court ruling. So, President Dwight D. Eisenhower got involved. He took control of the Arkansas National Guard. He ordered them to leave the school. Then he sent soldiers from the United States Army to protect the students. This was an important civil rights victory. It showed that the federal government would step in. It would force states to end segregation in schools.

Sadly, the Little Rock Nine were treated very badly by many white students. At the end of the school year, Little Rock Central High School closed. It did this so it would not have to allow black students the next year. Other schools across the South did the same thing.

-

President Dwight D. Eisenhower showed the government would force schools to integrate.

-

40th anniversary celebration of de-segregation at Little Rock High, led by President Bill Clinton.

Sit-ins (1958-1960): Peaceful Protests at Lunch Counters

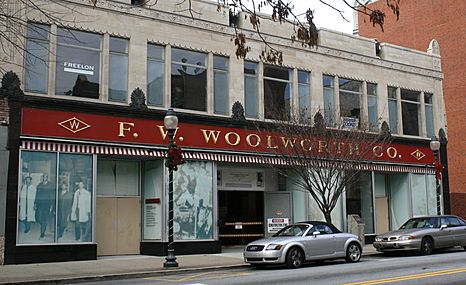

Between 1958 and 1960, activists used sit-ins. They did this to protest segregation at lunch counters (small restaurants inside stores). They would sit at the lunch counter and politely ask to buy food. When they were told to leave, they would keep sitting quietly. Often, they would stay until the lunch counter closed. Groups of activists would keep coming back to the same places. They did this until those places agreed to serve African Americans.

In 1958, the NAACP organized the first sit-in in Wichita, Kansas. It was at a lunch counter in a store called Dockum's Drug store. After its success, other sit-ins followed. They happened in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Greensboro, North Carolina; and Nashville, Tennessee.

Soon, sit-ins were happening all over the country. Sit-ins even took place in Nevada and northern states like Ohio. Over 70,000 people, both black and white, joined the sit-ins. They used sit-ins to protest all kinds of segregated places. This included not just lunch counters, but also beaches, parks, museums, libraries, swimming pools, and other public places.

President Eisenhower even supported the sit-ins. After the Greensboro sit-ins started, he said he felt "deeply sympathetic" with groups trying to get equal rights.

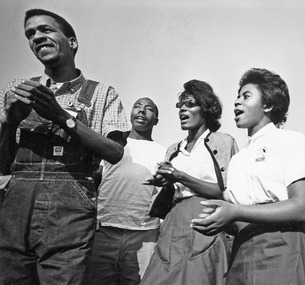

In April 1960, students who had led sit-ins were invited to a conference. At the conference, they decided to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC became a very important group in the civil rights movement.

-

Example of a 1950s lunch counter inside a drug store.

-

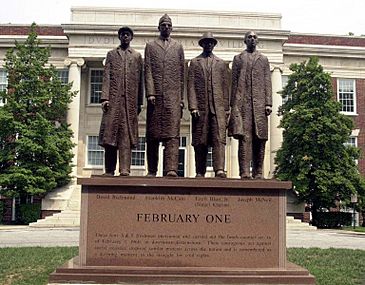

Monument to the four students who started the Greensboro sit-ins.

-

The Woolworth's five and dime store where the Greensboro students sat in.

-

A sign on a restaurant window in Lancaster, Ohio.

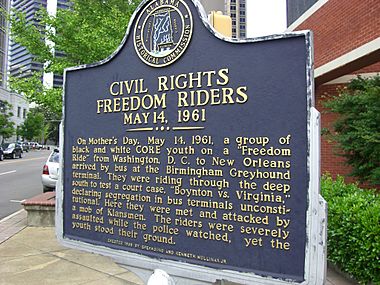

Freedom Rides (1961): Challenging Segregation on Buses

In 1960, the Supreme Court ruled in Boynton v. Virginia. It said that it was illegal to separate people on public transportation that traveled from one state to another. In 1961, student activists decided to test this ruling. They wanted to see if Southern states would follow it. Groups of black and white activists rode buses through the South. They sat together instead of separating themselves. They planned to ride buses from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans, Louisiana. They called these trips the "Freedom Rides."

The Freedom Riders faced danger and violence. For example:

- One bus in Alabama was firebombed. The Freedom Riders had to run for their lives.

- In Birmingham, Alabama, Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor let Ku Klux Klan members attack the Freedom Riders for 15 minutes. The police only "protected" them after that. The Riders were badly beaten. One needed 50 stitches in his head.

- In Montgomery, Alabama, a large, angry group of white people attacked the Freedom Riders. This caused a huge riot that lasted two hours. Five Freedom Riders had to go to the hospital. 22 others were hurt.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) brought in more Freedom Riders. They wanted to keep the movement going.

- In Montgomery, another mob attacked a bus. They knocked one activist unconscious. They also knocked out another's teeth.

- In Jackson, Mississippi, the Freedom Riders were arrested. They were arrested for using "white only" bathrooms and lunch counters.

- New Freedom Riders joined the movement. When they arrived in Jackson, they were also arrested. By the end of the summer, more than 300 had been put in jail.

A New Law for Travel

But people across the country began to support the Freedom Riders. The Riders had never used violence, even when attacked. Eventually, Robert F. Kennedy, who was the Attorney General (the top lawyer for the government), pushed for a new law. This law was about ending segregation in travel. It said that:

- People could sit wherever they chose on buses.

- There could be no "white" and "colored" signs in bus stations.

- There could be no separate drinking fountains, toilets, or waiting rooms for white and black people.

- Lunch counters had to serve people of all races.

-

The Ku Klux Klan were allowed to attack Freedom Riders in Montgomery. Here two children stand with a KKK leader.

-

Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy pushed for a new law about de-segregation.

-

John Lewis, now a U.S. Congressman, was attacked during a Freedom Ride.

Voter Registration (1961-1965): The Fight to Vote

Between 1961 and 1965, activist groups worked to get black people registered (signed up) to vote. Since the end of Reconstruction, Southern states had passed laws and used many tricks. They did this to stop black people from registering to vote. Often, these laws did not apply to white people.

Voter registration activists started in Mississippi. All of Mississippi's civil rights groups worked together to get people registered. Activist groups in Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina then started similar programs. But when activists tried to register black people, white racists did everything to stop them.

Meanwhile, black people who tried to register to vote were fired from their jobs. They were thrown out of their homes, beaten, arrested, threatened, and sometimes murdered.

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. It made discrimination illegal. It specifically said it was illegal to have different voter registration rules for different races.

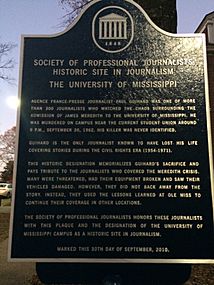

Integrating Mississippi Universities (1956-1965): Breaking Down Barriers

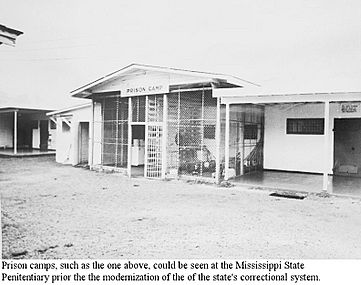

Starting in 1956, a black man named Clyde Kennard wanted to go to Mississippi Southern College. Kennard had served in the Korean War. He wanted to use the GI Bill to go to college. The college's president, William McCain, asked state politicians and a local racist group to make sure Kennard never got into the college.

Kennard was arrested twice for crimes he did not commit. He died of colon cancer in prison. Later, in 2006, a court ruled that Kennard was innocent of the crimes for which he had been jailed.

In September 1962, James Meredith won a lawsuit. It gave him the right to go to the University of Mississippi. He tried three times to enter the university to sign up for classes. Governor Ross Barnett blocked Meredith each time. He told Meredith: "[N]o school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your Governor."

Attorney General Robert Kennedy sent U.S. Marshals to protect Meredith. On September 30, 1962, Meredith was able to enter the college with the Marshals protecting him. But that evening, students and other racist white people started a riot. President John F. Kennedy sent the United States Army to the school to stop the riot. Meredith was able to start classes the day after the Army arrived. Meredith faced harassment and isolation at the college. He graduated on August 18, 1963, with a degree in political science.

Meredith and other activists kept working to end segregation in public universities. In 1965, the first two African American students were able to go to the University of Southern Mississippi.

-

Governor Ross Barnett refused to let Meredith into the University.

-

Memorial outside the University's School of Journalism, honoring the journalist who was killed during the riots.

Birmingham Campaign (1963): Children Join the Fight

In 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) started a campaign in Birmingham, Alabama. Its goals were to end segregation in downtown stores. They also wanted fair hiring practices. And they wanted a committee with both black and white people. This committee would plan how to end segregation in Birmingham's schools.

Birmingham's Commissioner of Public Safety was Eugene "Bull" Connor. He was in charge of the police and fire department. He also dealt with city emergencies. Connor was very much against integration.

The activists used different non-violent ways to protest. These included sit-ins, "kneel-ins" at churches, and marches. But the city got a court order saying all such protests were illegal. The activists knew this order was unfair. In an act of civil disobedience, they refused to follow it. The protesters, including Martin Luther King, were arrested.

While in jail, King was held alone in a cell. While there, he wrote his famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail." He was released after about a week.

The Children's Crusade: Young People Take a Stand

One of SCLC's leaders had an idea. He suggested training college, high school, and elementary school students to join the protests. He thought students did not have full-time jobs or families to care for. So, they could "afford" to be in jail more than their parents.

Newsweek magazine later called this plan the "Children's Crusade." On May 2, more than 600 students tried to march from a local church to City Hall. Some were as young as 8 years old. They were all arrested. The next day, another 1,000 students started to march. Bull Connor let police dogs attack them. He also used powerful fire hoses to knock the students down. Reporters were there. Videos and pictures showing the violence were shown on television and printed across the country.

An Agreement is Reached

People throughout the United States were very angry after seeing these videos. President Kennedy worked with the SCLC and white businesses in Birmingham to make an agreement. It said:

- Lunch counters and other public places downtown would end segregation.

- They would create a committee to stop discrimination in hiring.

- All jailed protesters would be released. (Labor unions like the AFL-CIO helped raise money for their bail.)

- Black and white leaders would talk regularly.

Some white people in Birmingham were not happy with this agreement. They bombed the SCLC's headquarters. They also bombed the home of King's brother and a hotel where King had been staying. Thousands of black people reacted by rioting.

On September 15, 1963, the Ku Klux Klan bombed a church in Birmingham. Civil rights activists often met there before their marches. Since it was a Sunday, church services were happening. The bomb killed four young girls and hurt 22 other people.

-

On May 11, a hotel where Dr. King had been staying was bombed.

"Rising Tide of Unhappiness" (1963): Protests Spread

In the spring and summer of 1963, protests happened in over a hundred U.S. cities. This included cities in the North. There were riots in Chicago after a white police officer shot a 14-year-old black boy. The boy was running away from a robbery. In Philadelphia and Harlem, black activists and white workers fought. This happened when activists tried to integrate state-run construction projects. On June 6, over a thousand white people attacked a sit-in in North Carolina. Black activists fought back.

In Cambridge, Maryland, white leaders declared martial law. They did this to stop fighting between black and white people. Attorney General Robert Kennedy had to get involved. He helped create an agreement to end segregation in the city.

On June 11, 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama. He did this to stop its first two black students from getting inside. President Kennedy had to send United States soldiers. They made him move and made sure the black students could enter the school.

Meanwhile, the Kennedy government became very worried. Black leaders told Robert Kennedy that it was getting harder for African Americans to stay nonviolent. This was happening because they were being attacked. Also, the U.S. government was taking so long to help them get their civil rights. On the evening of June 11, President Kennedy gave a speech about civil rights. He spoke about "a rising tide of discontent (unhappiness) that threatens the public safety." He asked Congress to pass new civil rights laws. He also asked Americans to support civil rights as "a moral issue ... in our daily lives."

In the early morning of June 12, Medgar Evers was murdered. He was a leader of the Mississippi NAACP. A Ku Klux Klan member killed him. The next week, President Kennedy gave Congress his Civil Rights bill. He asked them to make it into law.

-

Medgar Evers' home, where he was killed while getting out of his car.

-

Robert F. Kennedy speaking to civil rights activists in front of the Justice Department on June 14, 1963.

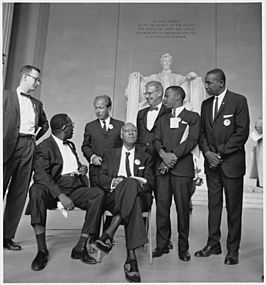

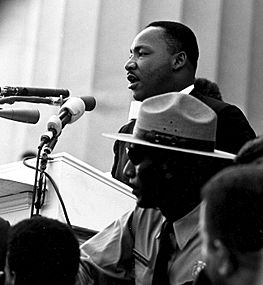

The March on Washington (1963): A Dream for Equality

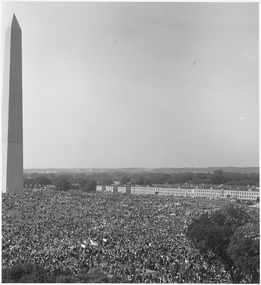

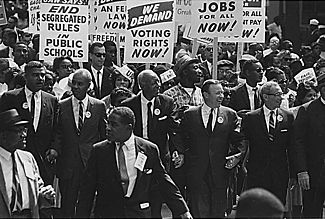

In 1963, civil rights leaders planned a protest march in Washington, D.C. The march's full name was "The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom." The goal of the march was to get the same rights for all people: black and white.

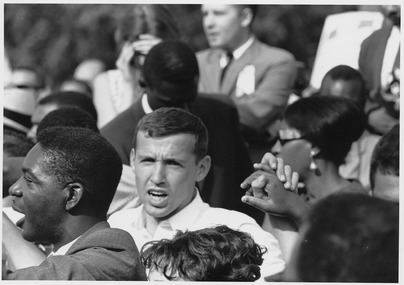

Many people thought it would be impossible for so many activists to come together without violence. The United States government got 19,000 soldiers ready nearby. They were prepared in case of riots. Hospitals got ready to treat many injured people.

The March on Washington was one of the largest non-violent protests for human rights in U.S. history. On August 28, 1963, about 250,000 activists came together for the march. They came from all over the country. The marchers included about 60,000 white people. This included church groups and labor union members. Between 75 and 100 members of Congress also marched. Together, they marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. There, they listened to civil rights leaders speak.

Martin Luther King, Jr., spoke last. His speech was called "I Have a Dream." It became one of history's most famous civil rights speeches.

Historians have said that the March on Washington helped President Kennedy's civil rights bill get passed.

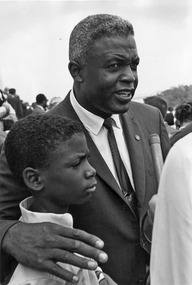

-

Marchers head toward the Lincoln Memorial.

-

Jackie Robinson and his son at the March.

Malcolm X Joins the Movement (1964): A New Voice

Malcolm X was an American minister. He became a Muslim while in prison around 1948. He joined the Nation of Islam. This group believed that black people were the best of all races. They thought black people should be completely independent from white people. They also believed black people should eventually return to Africa. They also thought black people had the right to fight back and use violence to get their rights. Because of this, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam did not support the civil rights movement. This was because it was non-violent and supported integration.

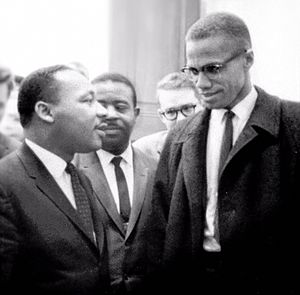

However, in March 1964, Malcolm X was kicked out of the Nation of Islam. He had disagreements with the group's leader, Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm offered to work with other civil rights groups. He said they must accept that black people had the right to defend themselves.

Malcolm met with Martin Luther King, Jr. on March 26, 1964. Malcolm had a plan to bring the United States before the United Nations. He wanted to accuse the U.S. of violating African Americans' human rights. Dr. King may have been planning to support this idea.

Between 1963 and 1964, civil rights activists became angrier. They were more likely to fight back. In April 1964, Malcolm gave a famous speech called "The Ballot or the Bullet." ("The ballot" means "voting.") In the speech, he said that if the U.S. government could not protect black people, then African Americans should defend themselves. He warned politicians that many African Americans were not willing "to turn the other cheek any longer." He also warned America about what would happen if black people were not allowed to vote.

-

Malcolm X in 1964.

-

Elijah Muhammad kicked Malcolm out of the Nation of Islam.

-

Painting honoring Malcolm (left) and other civil rights leaders.

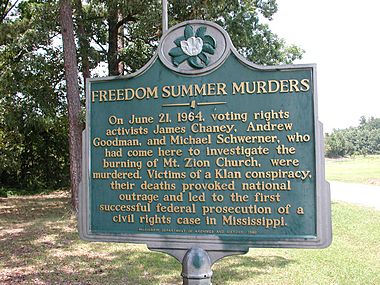

Mississippi Freedom Summer (1964): A Summer of Change

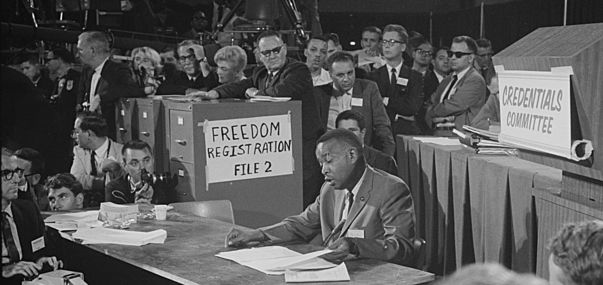

In the summer of 1964, civil rights groups brought almost 1,000 activists to Mississippi. Most of them were white college students. Their goals were to work with black activists to register voters. They also wanted to teach summer school to black children in "Freedom Schools." They also hoped to help create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP).

Many white Mississippians were angry. They did not like that people from other states were trying to change their society. They tried to stop black people from registering to vote.

During Freedom Summer, activists set up at least 30 Freedom Schools. They taught about 3,500 students. The students included children, adults, and the elderly. The schools taught many things. These included black history, civil rights, politics, the freedom movement, and basic reading and writing skills needed to vote.

Also during the summer, about 17,000 black Mississippians tried to register to vote. Only 1,600 were able to. However, more than 80,000 joined the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). This showed that they wanted to vote and take part in politics. They did not want to just let white people do it for them.

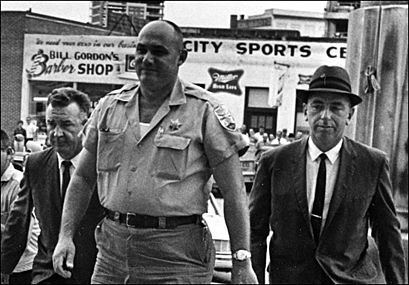

-

Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, who was part of the conspiracy, being taken to court.

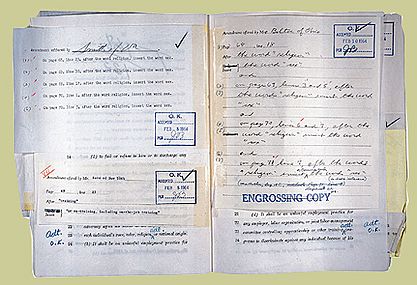

Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Major Victory

John F. Kennedy's suggested civil rights bill had support from Northern members of Congress. This included both Democrats and Republicans. But Southern Senators blocked the suggested law from passing. They used a tactic called a filibuster for 54 days. This stopped the bill from becoming a law. Finally, President Lyndon B. Johnson got a bill to pass.

On July 2, 1964, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The law said:

- It was illegal to treat people unfairly in public places or jobs because of their race, skin color, religion, sex, or home country.

- If places broke the law, the Attorney General could file lawsuits against them. This would force them to follow the law.

- Any state or local laws that allowed discrimination in public places or jobs were no longer legal.

-

Johnson spoke to the media after signing the Act.

King Awarded Nobel Peace Prize (1964): Global Recognition

In December 1964, Martin Luther King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. When giving him the award, the Chairman of the Nobel Committee said:

Today, now that mankind [has] the atom bomb, the time has come to lay our weapons and armaments aside and listen to the message Martin Luther King has given us: "The choice is either nonviolence or nonexistence"...

[King] is the first person in the Western world to have shown us that a struggle can be [fought] without violence. He is the first to make the message of brotherly love a reality in the course of his struggle, and he has brought this message to all men, to all nations and races.

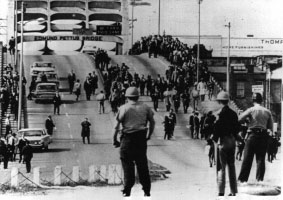

Selma to Montgomery Marches (1965): Marching for Voting Rights

In January 1965, Martin Luther King and the SCLC went to Selma, Alabama. Civil rights groups there had asked them to help get black people registered to vote. At the time, 99% of the people registered to vote in Selma were white. Together, they started working on voting rights.

The SCLC was worried that people would be angry about the violence against black people. So, they organized a 54-mile (87-kilometer) march. Activists hoped the march would show how much African Americans wanted to vote. They also wanted to show that they would not let racism or violence stop them from getting equal rights.

The marches took place between March 7 and 25. Sadly, many were injured or killed. The first day of the march became known as Bloody Sunday. Pictures and film of the marchers being beaten were shown in newspapers and on television around the world. Seeing these things made more people support the civil rights activists. People came from all over the United States to march with the activists.

Finally, President Johnson decided to send soldiers from the United States Army and the Alabama National Guard. They were sent to protect the marchers. From March 21 to March 25, the marchers walked along the "Jefferson Davis Highway" from Selma to Montgomery. On March 25, 25,000 people entered Montgomery. Martin Luther King gave a speech called "How Long? Not Long" at the Alabama State Capitol. He told the marchers that it would not be long before they had equal rights. He said, "because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

After the march, Viola Liuzzo, a white woman from Detroit, drove some other marchers to the airport. While she was driving back, three members of the Ku Klux Klan murdered her.

-

Memorial to Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan after the march.

-

The Obamas, ex-President George W. Bush, and civil rights activists march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

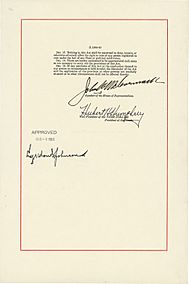

The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Making Voting Fair

On August 6, 1965, the United States passed the Voting Rights Act. This law made it illegal to stop someone from voting because of their race. This meant that all state laws that kept black people from voting were now illegal. The Voting Rights Act also said that if a registrar (the person who signs up voters) discriminated against black people, the Attorney General could send federal workers to replace local registrars.

The law worked right away. Within a few months, 250,000 new black voters had signed up to vote. Politics in the South changed completely. This was because African Americans now had the power to vote. White politicians could no longer make laws about African Americans without black people having a say. Also, black people who were registered to vote could be on juries. Before this, if an African American was accused of a crime, the jury that decided if they were guilty would be all-white.

-

President Johnson, Dr. King, and Rosa Parks at the signing of the Voting Rights Act.

Fair Housing Movements (1966-1968): Equal Homes for All

From 1966 to 1968, the civil rights movement focused a lot on fair housing. Even outside the South, fair housing was a problem.

Activists, including Martin Luther King, led a movement for fair housing in Chicago in 1966. The next year, young NAACP members did the same in Milwaukee. Activists in both cities were physically attacked by white homeowners. They were also legally attacked by politicians who supported segregation.

The Fair Housing Bill: A Difficult Fight

Of all the civil rights laws passed during the Civil Rights Movement, the Fair Housing Act was the hardest to pass. The law would make discrimination in housing illegal. This meant black people would be allowed to move into white neighborhoods. As Senator Walter Mondale said: "This was civil rights getting personal."

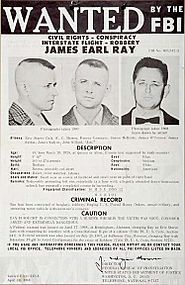

Many in Congress thought the bill gave too much power to black people. They wanted to make the bill weaker. However, on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was murdered. This made many members of Congress feel they needed to do something about civil rights quickly. The day after Dr. King's murder, Senator Mondale stood in front of the Senate. He asked them to immediately pass the bill. He also asked them to quickly provide housing and job opportunities for black people.

On April 10, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. President Johnson signed the law the next day. Part of the law is called the "Fair Housing Act." It makes it illegal to discriminate when selling, renting, or lending money for housing. This is based on a person's race, skin color, religion, or home country.

-

Senator Walter Mondale spoke in support of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

The King Assassination and the Poor People's Campaign (1968): A Legacy of Hope

In 1968, Martin Luther King and the SCLC were planning the Poor People's Campaign. People of all races took part in this movement. Its goal was to reduce poverty for everyone.

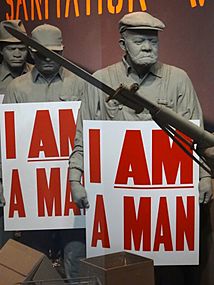

In March 1968, Dr. King spoke out against the Vietnam War. He was then invited to Memphis, Tennessee. He went to support garbage workers who were on strike. These workers were paid very little. Two workers had been killed doing their jobs. They wanted to be members of a labor union. Dr. King thought this strike fit perfectly with his Poor People's Campaign. As soon as he got to Memphis, King started getting threats.

The day before he was murdered, King gave a sermon called "I've Been to the Mountaintop." The next day, he was murdered. After King was killed, people rioted in more than 100 cities across the United States.

Civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy continued the Poor People's Campaign after King's death. About 3,000 activists camped out on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., for about six weeks.

The day before Dr. King's funeral, his wife, Coretta Scott King, and three of their children led 20,000 marchers through Memphis. Soldiers protected the marchers. On April 9, Mrs. King led another 150,000 people through Atlanta during Dr. King's funeral. An old, wooden wagon, pulled by mules, pulled Dr. King's casket. The wagon was a symbol of Dr. King's Poor People's Campaign.

Mrs. King once said:

[Martin Luther King, Jr.] gave his life for the poor of the world, the garbage workers of Memphis, and the peasants of Vietnam. The day that Negro people and others in bondage are truly free, on the day want is abolished, on the day wars are no more, on that day I know my husband will rest in a long-deserved peace.

-

The motel where King was murdered (now a museum). The wreath marks the spot where King was shot.

Deaths During the Movement

Many people were killed during the Civil Rights Movement. Some were killed because they supported civil rights. Others were killed by the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) or other racist white people. These groups wanted to terrorize black people. No one knows exactly how many people were killed during the Civil Rights Movement.

Quick Facts About the Civil Rights Movement

- The Civil Rights Movement in the United States started because African American people did not have the same rights as those with lighter skin. The movement's goal was to give every person equal rights.

- The movement is known for using non-violent protests and civil disobedience to get attention.

- The Civil Rights Movement included activists from different races and religions.

- Before the Civil War, there were many black slaves in the United States.

- In the South, Democrats did not support civil rights for black people. They started passing laws that took away the rights African Americans had gained. These became known as Jim Crow laws.

- The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in 1909. It used the law to try to get rights back for African Americans.

- In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that it was illegal for schools to be segregated. Until then, black children in the Democrat-run southern states were not allowed to go to the same schools as white children.

- Activists in the 1950s and 1960s worked together to get the attention of lawmakers. They organized events like a bus boycott, sit-ins, freedom rides, the children’s crusade, and the march on Washington.

- Martin Luther King and Malcolm X joined the movement. They became famous for how they helped the Civil Rights Movement.

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a big win for all African Americans. It said it was illegal to treat people unfairly in public places or jobs because of their race, skin color, religion, sex, or home country.

- The Civil Rights Movement was successful. It helped change both laws and how many white people felt about the way black people were treated.

Related Topics

- History: Slavery; American Civil War; Reconstruction; Plessy v. Ferguson

- Causes: Racism; white supremacy; racial segregation; discrimination; Jim Crow laws

- People: Martin Luther King, Jr.; Coretta Scott King; James Lawson; James Meredith; Little Rock Nine; Rosa Parks; Malcolm X

- Groups: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC);

- Law & government: Law of the United States; case law; federal law; legislation; Constitution of the United States; Supreme Court; United States Congress

- Rights: Civil rights; civil liberties; human rights; right to vote; social equality; social justice

- Other: Ku Klux Klan; sundown towns; White Citizens' Council

Images for kids

-

KKK night rally near Chicago, in the 1920s.

-

A white gang looking for blacks during the Chicago race riot of 1919.

-

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

-

Malcolm X meets with Martin Luther King Jr., March 26, 1964.

-

White segregationists (foreground) trying to prevent black people from swimming at a "White only" beach in St. Augustine during the 1964 Monson Motor Lodge protests.

-

Lyndon B. Johnson signs the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964.

-

President Lyndon B. Johnson (center) meets with civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Whitney Young, and James Farmer, January 1964.

-

Fannie Lou Hamer of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (and other Mississippi-based organizations) is an example of local grassroots leadership in the movement.

-

Armed Lumbee Indians aggressively confronting Klansmen in the Battle of Hayes Pond.

-

Jewish civil rights activist Joseph L. Rauh Jr. marching with Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963.

-

Gold medalist Tommie Smith (center) and bronze medalist John Carlos (right) showing the raised fist on the podium after the 200 m race at the 1968 Summer Olympics; both wear Olympic Project for Human Rights badges. Peter Norman (silver medalist, left) from Australia also wears an OPHR badge in solidarity with Smith and Carlos.

See also

In Spanish: Movimiento por los derechos civiles en Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Movimiento por los derechos civiles en Estados Unidos para niños