Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee facts for kids

|

|

| Abbreviation | SNCC |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1960 |

| Founder | Ella Baker |

| Dissolved | 1970 |

| Purpose | Civil rights movement Participatory democracy Pacifism Black Power |

| Headquarters | Atlanta, Georgia |

|

Region

|

Deep South and Mid-Atlantic |

|

Main organ

|

The Student Voice (1960–1965) The Movement (1966–1970) |

| Subsidiaries | Friends of SNCC Poor People's Corporation |

| Affiliations | |

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced SNIK) was a very important group during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. It was mainly made up of students.

SNCC started in 1960 after students held sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. These sit-ins happened in places like Greensboro, North Carolina and Nashville, Tennessee. The group wanted to help organize protests against racial segregation and to help African Americans get their right to vote.

From 1962, SNCC focused on registering Black voters in the Deep South. Groups like the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party helped push the government to protect civil rights.

Later in the 1960s, some members felt that progress was too slow. They also saw how much violence they faced. This led to disagreements about using nonviolence and having white people in the movement. SNCC eventually stopped working around 1970.

SNCC is remembered for breaking down barriers. It helped empower African-American communities.

Contents

How SNCC Started in 1960

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was created in April 1960. This happened at a meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina. Over 120 students from many states attended.

Martin Luther King Jr. invited them, but Ella Baker organized the meeting. Baker believed that "Strong people don't need strong leaders." She wanted the students to lead themselves.

SNCC decided to be an independent group. It focused on supporting activists working in local communities. Decisions were made by everyone involved, not just a few leaders. This was called "participatory democracy". Everyone could speak, and decisions needed everyone's agreement. This was important because their work was often dangerous.

At first, SNCC continued with sit-ins and boycotts. They targeted places that separated people by race. In 1961, SNCC members like Diane Nash started a new tactic. They chose to stay in jail instead of paying bail. This "Jail-no-Bail" idea saved money and showed they would not accept unfair laws.

SNCC students also did "kneel-ins" outside churches that separated people. They wanted to show that even churches were segregated.

Freedom Rides in 1961

In May 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) started the first Freedom Rides. These rides tested if Southern states were following Supreme Court rules. The rules said that segregation on buses and trains between states was illegal.

The first riders faced violent attacks in Anniston, Alabama. Police did not help them. After more attacks, CORE thought about stopping the rides. But Diane Nash and other SNCC members decided to continue.

New riders, including John Lewis and Stokely Carmichael, joined. They were severely beaten in Montgomery, Alabama. Many were arrested and sent to a tough prison called "Parchman Farm" in Mississippi.

SNCC's determination led CORE and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to keep the rides going. More than 60 Freedom Rides happened that summer. Most riders were arrested in Jackson, Mississippi.

Finally, the government made new rules. From November 1, 1961, people could sit anywhere on interstate buses and trains. Signs like "white" and "colored" had to be removed from terminals.

To test these new rules, SNCC members went to Albany, Georgia. They led a sit-in at the bus terminal. By December, over 500 protesters were jailed. Martin Luther King Jr. joined them briefly. He left after the city promised to follow the rules, but the city did not keep its word. Protests continued into 1962.

Helping People Vote in 1962

In 1962, the Voter Education Project (VEP) was formed. It helped fund efforts to register Black voters in the South. Some students worried this was a way for the government to control their movement. But others believed that voting was key to gaining power for Black Americans.

Older Black Southerners had already been asking SNCC to focus on voting. Amzie Moore, a leader from Mississippi, suggested a voter registration drive in 1960.

There was a debate within SNCC about whether to focus on direct action or voter registration. Ella Baker suggested having two groups: one for direct action and one for voting. But after activists faced violence while trying to register voters in Mississippi, many realized that voter registration was also a direct challenge to unfair systems.

In 1962, Bob Moses helped create the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). This group included SNCC, the NAACP, and other organizations. With funding, SNCC expanded its voter registration work. They worked in places like Greenwood, Mississippi, Albany, Georgia, and Selma, Alabama. These projects faced police harassment, arrests, and violence.

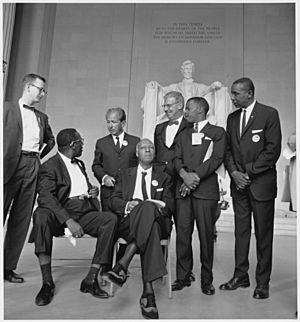

March on Washington in 1963

SNCC played a big part in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This march is famous for Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech.

However, SNCC disagreed with other groups about the government's Civil Rights Bill. John Lewis, representing SNCC, planned to give a strong speech. He wanted to say that the bill did not do enough to protect people from violence. He also questioned which side the government was on.

Other groups pressured Lewis to change his speech. He changed "We cannot support" the bill to "we support with reservations." Some SNCC members felt this was a compromise that weakened their message.

During the march, women were told to walk separately from men. Only men were scheduled to speak at the main rally. Women like Casey Hayden and Daisy Bates protested this. A few women were allowed on stage, and Daisy Bates gave a short speech. This experience made many women realize they also needed to fight for their rights as women.

Leesburg Stockade Incident

In July 1963, SNCC organized a protest in Americus, Georgia. They marched on a segregated movie theater. Over 30 high school girls were arrested. These "Stolen Girls" were held for 45 days in terrible conditions at the Leesburg Stockade. SNCC photographer Danny Lyon secretly took pictures inside. This helped bring national attention to their case.

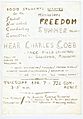

Freedom Summer in 1964

In late 1963, SNCC held a practice election in Mississippi. Over 80,000 Black Mississippians voted, even though they were usually prevented from doing so. This showed they wanted to vote.

In 1964, SNCC and CORE launched the Mississippi Summer Project, also known as Freedom Summer. Over 700 white students from the North volunteered. They worked as teachers and organizers.

One reason for inviting white students was to get media attention. Sadly, two white students, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, were killed along with local activist James Chaney. This tragedy brought a lot of attention to Freedom Summer.

A main goal of Freedom Summer was to create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). This party would send Black and white delegates to the 1964 Democratic National Convention. They wanted to challenge the all-white Mississippi delegation.

SNCC also set up over 40 Freedom Schools in Mississippi. More than 3,000 students attended. These schools helped young people learn and get involved in the movement.

Democratic Convention Challenge

In August 1964, the bodies of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were found. They had been missing for weeks. This led to a large search and brought more attention to the violence in Mississippi.

Despite the outrage, the government tried to stop the MFDP at the Democratic Convention. They wanted to avoid upsetting Southern white voters. SNCC field secretary Fannie Lou Hamer spoke powerfully at the convention. She described the terrible conditions for Black farmers and the violence she faced when trying to vote.

The Democratic Party offered the MFDP only two seats where they could watch but not vote. Fannie Lou Hamer refused this offer. She said, "We didn't come all this way for no two seats when all of us is tired."

This event made many activists feel betrayed by the Democratic Party. It made them question their work on voter registration.

New Directions in 1965

By the end of 1964, SNCC had many staff members. But many felt lost after the events at the Democratic Convention. The violence and the large number of white volunteers also caused tension. Black staff felt frustrated by the challenges.

Even though the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed, faith in the government was low. Fannie Lou Hamer said she "lost hope in American society."

SNCC leaders debated how the group should be organized. Some wanted a more structured group. Others, like Bob Moses, believed that leaders should come from the people themselves. He said, "Leadership is there in the people."

Black Power Movement in 1966

Carmichael and Black Power

In May 1966, Stokely Carmichael became SNCC's new chairman. After being arrested for the 27th time, he asked a crowd, "What do you want?" They shouted back, "Black Power! Black Power!"

For Carmichael, Black Power meant Black people should set their own goals. They should lead their own organizations. He said, "We have to organize ourselves to speak from a position of strength."

SNCC began to focus on organizing in cities. They worked in Atlanta, Georgia. They also supported Julian Bond when he was not allowed to take his seat in the Georgia Legislature. This was because SNCC opposed the Vietnam War.

A paper from the "Vine City" project in Atlanta explained Black Power. It said that Black people had not been allowed to organize themselves because of white interference. It suggested that white people's presence could make Black people feel intimidated.

The paper said that white people had helped the movement a lot, especially during Freedom Summer. But it argued that their role was now over. It said that Black people needed "all-Black projects" to truly free themselves. Future cooperation with white people should be as "coalitions." White people should work to fight racism in their own communities.

Many SNCC leaders agreed that white organizers could sometimes make Black people less confident. In December 1966, SNCC decided to ask white co-workers to leave. They felt white people should focus on organizing poor white communities.

Lowndes County and the Black Panther Symbol

Carmichael also worked on a voter registration project in Alabama. In Lowndes County, Alabama, organizers for the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) openly carried guns to protect themselves from violence.

John Hulett and another man became the first two Black voters in Lowndes County in over 60 years. Carmichael helped form the LCFO with Hulett. This group not only registered voters but also ran candidates for office. Their symbol was a black panther, showing Black "strength and dignity."

Hulett warned that if Black people were stopped from gaining power legally, they would take it another way. He said, "if one of our candidates gets touched, we're going to take care of the murderer ourselves."

Working Together for Change

Some white activists were confused by the call for Black Power. But many understood that Black people needed to lead their own fight. The message to white activists was to "organize your own" communities.

This led to the idea of an "interracial movement of the poor." The goal was no longer just integration. It was about different groups working together, like the "rainbow coalition" later suggested by the Black Panther Party.

White volunteers who left SNCC joined other groups. They worked to organize white students and poor white people.

SNCC Against the Vietnam War

In January 1966, Sammy Younge Jr. was killed. He was the first Black college student killed for his civil rights work. SNCC used this event to speak out against the Vietnam War. This was the first time a major civil rights group did this.

SNCC said that the killing of Sammy Younge was like the killing of people in Vietnam. They argued that the U.S. government was responsible for both. They questioned why Black people were asked to fight for freedom in Vietnam when they didn't have it at home.

In October 1966, Carmichael challenged white activists to resist the military draft. SNCC had already protested at a draft office in Atlanta. The slogan "Hell no! We won't go!" became popular.

SNCC's Later Years: 1967–1970

By early 1967, SNCC was running out of money. The call for Black Power and the departure of white activists made it harder to get funding. SNCC organizers also started moving to Northern cities. They saw that civil rights victories in the South did not solve problems in urban areas.

SNCC worked on projects in cities like Washington, D.C., and New York City. They fought for local control of schools and monitored police. They also worked to build independent political parties.

In May 1967, Carmichael stepped down as chairman. He traveled to other countries and spoke against U.S. policy. In 1968, he joined the Black Panther Party. He wanted to create a nationwide Black United Front.

H. Rap Brown became the new SNCC chairman. He also believed that nonviolence was a tactic, not a rule. He famously said that violence was "as American as cherry pie."

In June 1968, SNCC leaders decided not to work with the Black Panthers. There was a serious argument between SNCC and Panther leaders. Carmichael was expelled from SNCC.

Rap Brown resigned as chairman after being accused of starting a riot. In March 1970, two SNCC workers died in a car explosion. The cause of the explosion is still debated.

Why SNCC Ended

| Marion Barry | 1960–61 |

| Charles F. McDew | 1961–63 |

| John Lewis | 1963–66 |

| Stokely Carmichael | 1966–67 |

| H. Rap Brown | 1967–68 |

| Phil Hutchings | 1968–69 |

Ella Baker said that SNCC came North when there were many different ideas about what to do. SNCC could not lead in the North as it had in the South.

The FBI also targeted SNCC. The FBI tried to "expose, disrupt, discredit, or otherwise neutralize" groups they saw as a threat.

By 1970, SNCC's activities had mostly stopped. Many experienced organizers had left. The years of hard work and low pay were very difficult. Some joined the Black Panthers. Others joined government programs like the War on Poverty.

Charles McDew, an early SNCC chairman, believed the group was not meant to last long. He thought it would last about five years. He said, "by the end of that time you'd either be dead or crazy."

Even after it ended, SNCC had a lasting impact. It helped break down mental and physical barriers for Black Southerners. Julian Bond said SNCC "helped break those chains forever." It showed that ordinary people could do amazing things.

Women in SNCC

Ella Baker wanted SNCC to be different from other groups where men were always in charge. In SNCC, Black women became very strong and brave organizers and thinkers.

Many important women were part of SNCC. These included Diane Nash, Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Oretha Castle Haley. Other women like Gwen Patton, Cynthia Washington, and Muriel Tillinghast also played key roles.

Anne Moody remembered that women did a lot of the work. Young Black women students and teachers were central to voter registration and the Freedom Schools. Women were often the local leaders. One activist said there was always a "mama" in the community. This was usually a strong, outspoken woman ready to face challenges.

White students also joined the movement. Casey Hayden and Mary King were among the first white women in SNCC. Hayden felt the fight against segregation was her fight too. But she also knew she was a "guest" when working in Black communities. Most white women volunteers came from the North for Freedom Summer in 1964.

"Sex and Caste" Paper

In 1964, a paper was shared at a SNCC meeting. It pointed out that a committee formed to discuss changes was "all men." It also said that ideas of male superiority were as harmful to women as white supremacy was to Black people.

This was not the first time women raised concerns. In 1964, a group of women protested in James Forman's office. They were tired of being expected to do all the office tasks. Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson held a sign saying, "No More Minutes Until Freedom Comes to the Atlanta Office."

Casey Hayden and Mary King were authors of the paper. They later wrote a longer version called "Sex and Caste." This article compared how women were treated to how African Americans were treated. It said women were "caught up in a common-law caste system." This paper is seen as an important text for second-wave feminism.

Black Women's Liberation

Some Black women disagreed about how much men dominated SNCC. They said it did not stop them from being leaders. For example, Joyce Ladner remembered "women's full participation" during Freedom Summer.

Historian Barbara Ransby argues that women's roles did not shrink during the Black Power period. She notes that Stokely Carmichael appointed several women to lead projects. More women were in charge of SNCC projects in the late 1960s than in earlier years.

However, Frances M. Beal felt that as SNCC focused more on Black Power, male dominance increased. In 1968, she and others formed the SNCC Black Women's Liberation Committee. They wanted to address these issues.

After SNCC broke up, this committee became the Third World Women's Alliance in 1970. This group was one of the first to talk about "triple oppression" – the idea that women face challenges because of their race, class, and gender.

Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, who helped write the Black Power paper, later became an "Islamic feminist." She saw a big difference between SNCC, where women could lead, and other groups that had strict gender roles.

Fannie Lou Hamer also helped start the National Women's Political Caucus in 1971. She believed women could be a powerful voting group, regardless of their race. She said, "A white mother is no different from a black mother." The NWPC still works to support women running for office.

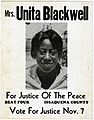

Images for kids

-

Photograph of Gwendolyn Zoharah Simmons, taken during 2011 oral history interview.

H. Rap Brown

Unita Blackwell

See also

In Spanish: Comité Coordinador Estudiantil No Violento para niños

In Spanish: Comité Coordinador Estudiantil No Violento para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |