Stokely Carmichael facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kwame Ture

|

|

|---|---|

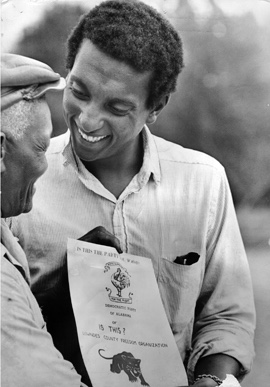

Carmichael in 1966

|

|

| 4th Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee | |

| In office May 1966 – June 1967 |

|

| Preceded by | John Lewis |

| Succeeded by | H. Rap Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael

June 29, 1941 Port of Spain, British Trinidad and Tobago |

| Died | November 15, 1998 (aged 57) Conakry, Guinea |

| Spouses |

Marlyatou Barry (divorced) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Howard University (BA) |

Kwame Ture (born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941 – November 15, 1998) was an important leader in the civil rights movement in the United States. He also played a big role in the global pan-African movement.

Born in Trinidad, he moved to the United States at age 11. He became an activist while attending high school. He was a key leader in the Black Power movement. He led the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and was an "Honorary Prime Minister" of the Black Panther Party. Later, he led the All-African People's Revolutionary Party (A-APRP).

Carmichael was one of the first SNCC freedom riders in 1961. He became a major activist for voting rights in Mississippi and Alabama. He learned a lot from leaders like Ella Baker and Bob Moses. He became unhappy with the two main political parties after the 1964 Democratic National Convention. This event did not recognize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Carmichael decided to create independent Black political groups. These included the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. He was inspired by Malcolm X and developed the idea of Black Power. He made this idea popular through speeches and writings. Carmichael became one of the most well-known Black leaders of the late 1960s. He moved to Africa in 1968. There, he changed his name to Kwame Ture. He worked internationally for revolutionary socialist pan-Africanism. Ture died in 1998 at age 57.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Carmichael was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago. He moved to Harlem, New York City, in 1952 when he was 11. He rejoined his parents, who had moved to the U.S. when he was two. He had three sisters.

His mother, Mabel R. Carmichael, worked on a steamship. His father, Adolphus, was a carpenter and taxi driver. The family later moved to Van Nest in the East Bronx.

Carmichael went to The Bronx High School of Science in New York. He was accepted because of his high test scores. While there, he joined a protest against a restaurant that did not hire Black people.

After high school in 1960, Carmichael went to Howard University. This is a historically Black university in Washington, D.C.. His teachers included the famous writer Toni Morrison.

Carmichael's apartment in Washington, D.C., was a meeting place for his activist friends. He graduated in 1964 with a degree in philosophy. He was offered a scholarship to Harvard University but turned it down.

At Howard, Carmichael joined the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG). This group was part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He became very active in the Civil Rights Movement.

Freedom Rides and Early Activism

In 1961, Carmichael took part in the Freedom Rides. These rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Their goal was to end segregation on buses and in bus station restaurants. He was arrested many times for his activism. He estimated he was arrested 29 or 32 times.

On June 4, 1961, Carmichael and eight other riders traveled by train to Jackson, Mississippi. They wanted to integrate the "white" section of the train. Before boarding, white protesters shouted at them and threw things. The group eventually got on the train. In Jackson, they entered a "white" cafeteria. They were arrested for disturbing the peace.

Carmichael was sent to the Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi. He became known as a strong leader among the prisoners. He spent 49 days there. At 19, he was the youngest person held there that summer. He and others were allowed to shower only twice a week. They had no books or personal items. Sometimes they were put in isolation.

One time, when he was hurt, Carmichael started singing to the guards. He sang, "I'm gonna tell God how you treat me." Other prisoners joined in. He helped keep everyone's spirits up in prison.

SNCC Leadership and Black Power

Working in Mississippi and Maryland

In 1964, Carmichael became a full-time organizer for SNCC in Mississippi. He worked on a project to help Black people register to vote. He worked with local activists like Fannie Lou Hamer.

He also worked with Gloria Richardson in Cambridge, Maryland. During a protest in June 1964, Carmichael was hurt by chemical gas from the National Guard. He had to go to the hospital.

He became the project director for Mississippi's 2nd congressional district. Most Black people in Mississippi could not vote at this time. The summer project helped them prepare to register. Local activists formed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). This was because the regular Democratic Party did not represent Black Americans.

Carmichael went to the 1964 Democratic Convention to support the MFDP. But the MFDP delegates were not allowed to vote. Many SNCC members, including Carmichael, felt very disappointed. He called it "totalitarian liberal opinion." He said, "what the liberal really wants is to bring about change which will not in any way endanger his position."

Selma to Montgomery Marches

After the 1964 convention, Carmichael did not want to work with the Democratic Party. He started exploring SNCC projects in Alabama in 1965. He joined protests at the Alabama State Capitol during the Selma to Montgomery marches. He became frustrated with the nonviolent protests. He felt they were no longer effective. After seeing protesters beaten again, he became very stressed.

Within a week, Carmichael returned to protest in Selma. He joined the final march to the state capital. But on March 23, 1965, Carmichael and some SNCC members left the march. They started a project in "Bloody Lowndes" County. This county was known for white violence against Black people. Carmichael and SNCC struggled at first. But they gained success by working with local activist John Hulett.

Lowndes County Freedom Organization

In 1965, Carmichael worked in Lowndes County, Alabama. He helped increase the number of registered Black voters from 70 to 2,600. This was more than the number of white voters. Black people had been prevented from voting by Alabama's constitution since 1901. After the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the federal government could enforce their rights.

Carmichael and his allies formed the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). This party had a black panther as its symbol. The local Democratic Party had a white rooster. Many Lowndes County activists carried guns for protection.

John Hulett became the LCFO's chairperson. He was one of the first Black Americans to successfully register to vote in Lowndes County. In 1966, LCFO candidates ran for office but lost. In 1970, the LCFO joined the state Democratic Party. Former LCFO candidates, including Hulett, then won their first offices.

Chairman of SNCC and Black Power

Carmichael became chairman of SNCC in 1966. He took over from John Lewis. In June 1966, James Meredith started a solo March Against Fear from Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi. Meredith was shot and wounded. Civil rights leaders promised to finish the march.

Carmichael joined Martin Luther King Jr., Floyd McKissick, and others to continue the march. He was arrested in Greenwood during the march.

Carmichael spoke about Black Power at a rally during the march. This brought the idea into the national spotlight. It became a rallying cry for young Black Americans. They were frustrated by the slow progress in civil rights. Carmichael said, "Black Power meant black people coming together to form a political force." He believed they should elect representatives or make them address their needs.

Carmichael was influenced by Frantz Fanon and Malcolm X. He led SNCC to focus more on Black Power. He believed nonviolence was a tactic, not a core belief. He criticized leaders who wanted Black Americans to join existing middle-class institutions.

Carmichael wrote, "in order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none."

Under Carmichael, SNCC started actions against the Vietnam War. He made popular the anti-draft slogan "Hell no, we won't go!" He encouraged King to demand that U.S. troops leave Vietnam.

Transition and International Work

Stepping Down from SNCC

In May 1967, Carmichael stepped down as SNCC chairman. He was replaced by H. Rap Brown. Some SNCC members were unhappy with Carmichael's fame. They felt he made policy announcements without group agreement. Carmichael was "eager to relinquish the chair." SNCC officially ended its relationship with Carmichael in August 1968.

Targeted by the FBI

During this time, Carmichael was targeted by the FBI's COINTELPRO program. This program tried to harm Black activists. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover saw Carmichael as a major threat. In July 1968, Hoover tried to divide the Black Power movement. He also tried to make people think Carmichael was a CIA agent. These efforts were largely successful. Carmichael was expelled from SNCC. The Black Panthers also started to criticize him.

International Activism and Black Power Book

After leaving SNCC's leadership, Carmichael wrote the book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (1967) with Charles V. Hamilton. The book shares his experiences in SNCC. It also shows his unhappiness with the Civil Rights Movement's direction. He criticized the leaders of the SCLC and NAACP. He felt they accepted symbols instead of real change.

He promoted "political modernization." This meant questioning old values and institutions. It also meant finding new political structures to solve problems. And it meant more people joining in decision-making. He criticized the focus on the American "middle-class." He believed Black people were being tricked into joining the middle-class. He thought this would make them turn their backs on other Black people who were still suffering.

Carmichael believed that Black people needed to unite and build their own power. This would be separate from white structures. He felt this was needed for any true partnership between groups. He said, "we want to establish the grounds on which we feel political coalitions can be viable."

He continued to criticize the Vietnam War and imperialism. He traveled and lectured around the world. He visited Guinea, North Vietnam, China, and Cuba. He became known as the "Honorary Prime Minister" of the Black Panther Party.

In July 1967, Carmichael visited the United Kingdom. He was later banned from reentering Britain. In August 1967, he met with Fidel Castro in Cuba. The U.S. government took away his passport because relations with Cuba were forbidden.

1968 D.C. Riots

Carmichael was in Washington, D.C., on April 5, 1968. This was the night after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.. He led a group through the streets. He asked businesses to close out of respect. He tried to stop violence, but the situation got out of control. News media blamed Carmichael for the riots.

The FBI watched Carmichael closely. After the riots, Hoover tried to link Carmichael to them. Huey P. Newton suggested Carmichael was a CIA agent. This led to Carmichael's break with the Panthers. He left the U.S. the next year.

Life in Africa and Pan-Africanism

In 1968, he married Miriam Makeba, a famous singer from South Africa. They left the U.S. for Guinea in 1969. Carmichael became an aide to Guinean president Ahmed Sékou Touré. He also studied with the exiled Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah.

Break with Black Panthers

In July 1969, Carmichael formally rejected the Black Panthers. He said they were not separatist enough. He also criticized their alliances with white radicals. Carmichael believed white activists should organize their own communities first.

Life in Africa

Carmichael stayed in Guinea. He continued to travel, write, and speak for international leftist movements. In 1971, he published Stokely Speaks: From Black Power to Pan-Africanism. This book showed his socialist Pan-African vision. He kept this vision for the rest of his life.

Carmichael changed his name to Kwame Ture in 1978. This honored Nkrumah and Touré. Friends called him by both names.

In 1986, Ture was arrested in Guinea. This was because of his connection to Sékou Touré. He was jailed for three days. From the late 1970s until his death, he answered his phone by saying, "Ready for the revolution!"

All-African People's Revolutionary Party

For the last 30 years of his life, Kwame Ture worked for the All-African People's Revolutionary Party (A-APRP). His mentor Nkrumah had ideas for uniting Africa. Ture expanded these ideas to all people of African descent around the world. He was a Central Committee member of the A-APRP. He gave many speeches for the party.

Ture worked to "Take Nkrumah Back to Ghana." He became a member of the Democratic Party of Guinea (PDG). He got Nkrumah's permission to start the A-APRP.

Ture believed the A-APRP was needed in all countries where people of African descent lived. He worked full-time as an organizer for the party. He spoke on several continents. He helped strengthen ties between the African/Black liberation movement and other revolutionary groups. These included the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

Ture was often seen as the leader of the A-APRP. But his only titles were "Organizer" and Central Committee member. The A-APRP started sponsoring African Liberation Day (ALD) each May. This continued Nkrumah's African Freedom Day. The largest ALD event was held annually in Washington, DC.

Lecturing in the Caribbean and the United States

Ture traveled often while living in Guinea. He became the world's most active supporter of pan-Africanism. He defined it as "The Liberation and Unification of Africa Under Scientific Socialism."

Ture often returned to speak at his old university, Howard University. He spoke to thousands of students and community members. The Party worked to recruit young people. Ture wanted to raise the political awareness of African/Black people. He wanted to make them connect with their ancestral homeland. The government of Trinidad and Tobago banned him from lecturing there. They feared he would cause problems among Black Trinidadians.

Under his leadership, the A-APRP organized the All African Women's Revolutionary Union. They also formed the Sammy Younge Jr. Brigade.

Ture and Cuban president Fidel Castro admired each other. They both opposed imperialism.

Ture was ill when he gave his last speech at Howard University. He spoke boldly, as always. A small group of students and friends said goodbye to Ture before he returned to Guinea.

Illness and Death

In 1996, Ture was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He was treated in Cuba. He also received support from the Nation of Islam. Benefit concerts were held to help pay for his medical costs. The government of Trinidad and Tobago gave him $1,000 a month. He was treated in New York for two years. Then he returned to Guinea.

In an interview in April 1998, Ture criticized the limited progress Black Americans had made in the U.S. He said that Black people had won elections in major cities. But he felt the power of mayors had decreased. So, he thought this progress was not very meaningful.

In 1998, Ture died of prostate cancer at age 57 in Conakry, Guinea. He believed his cancer "was given to me by forces of American imperialism." He claimed the FBI had infected him as an assassination attempt.

Civil rights leader Jesse Jackson praised Ture's life. He said, "He was one of our generation who was determined to give his life to transforming America and Africa." NAACP Chair Julian Bond said Carmichael "ought to be remembered for having spent almost every moment of his adult life trying to advance the cause of black liberation."

Personal Life

Ture married Miriam Makeba in the U.S. in 1968. They divorced in Guinea in 1973.

Later, he married Marlyatou Barry, a Guinean doctor. They divorced after having a son, Bokar, in 1981. By 1998, Marlyatou Barry and Bokar lived in Arlington County, Virginia. Ture's obituary mentioned he was survived by two sons, three sisters, and his mother.

Legacy

Ture, with Charles V. Hamilton, is known for coining the phrase "institutional racism". This means racism that happens through organizations like public bodies and companies. In the late 1960s, Ture defined it as "the collective failure of an organization to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their color, culture or ethnic origin."

Historian David J. Garrow said Ture's work in registering 2,600 Black voters in Lowndes County was his most important achievement. This had a real, positive impact on people's lives. Some people praise his efforts. Others criticize him for not finding better ways to reach his goals.

Historian Peniel Joseph said Ture expanded the civil rights movement. He said Ture's Black Power strategy "didn't disrupt the civil rights movement." It spoke to what many young people felt. It also highlighted people in prisons and activists for welfare and tenants' rights. Tavis Smiley called Ture "one of the most underappreciated, misunderstood, undervalued personalities this country's ever produced."

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Ture as one of his 100 Greatest African Americans.

Ture is also remembered for his actions in James Meredith's March Against Fear in June 1966. He called for Black Power during this march. He was angry that Black people had been "chanting" freedom for years with no results. He wanted to change the chant. He never changed his political views as he got older. His life influenced the path of Black activism in the United States. King's assassination deeply affected him.

Works

- Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (1967) ISBN: 0679743138

- Stokely Speaks: From Black Power to Pan-Africanism (1965) ISBN: 978-1-55652-649-7

- Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (2005) ISBN: 978-0684850047

See also

In Spanish: Stokely Carmichael para niños

In Spanish: Stokely Carmichael para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |