Freedom Riders facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Freedom Riders |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

|

|||

| Date | May 4 – December 10, 1961 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

The Freedom Riders were brave activists who rode buses across different states in the Southern United States in 1961. They did this to challenge unfair laws that separated people by race, known as racial segregation. Even though the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that segregated public buses were against the law, many Southern states ignored these rulings. The government also did not do much to make sure the rules were followed.

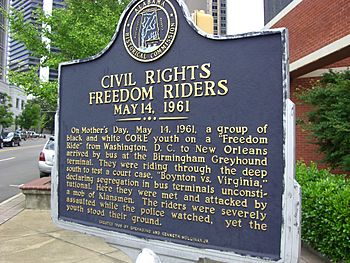

The first Freedom Ride started on May 4, 1961, from Washington, D.C.. It was planned to end in New Orleans on May 17. A Supreme Court decision called Boynton v. Virginia (1960) had made it illegal to separate people by race in restaurants and waiting rooms at bus stations that served buses traveling between states. Before that, in 1955, another ruling had also said that "separate but equal" was not allowed for interstate bus travel. But these rules were not enforced, and old segregation laws, called Jim Crow laws, stayed in place.

The Freedom Riders challenged these unfair rules by riding buses in mixed groups of Black and white people. They wanted to show that segregation was still happening and that it was wrong. The Freedom Rides, and the violent reactions they caused, helped the American Civil Rights Movement gain more support. They showed the whole country how federal laws were being ignored and how much violence was used to keep segregation going in the South. Police often arrested the Riders for minor reasons, but sometimes they let angry white mobs attack the Riders first without helping.

Most of the Freedom Rides were organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Some were also organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). These rides happened after many students had already started sit-in protests at segregated lunch counters and boycotts of stores that separated people by race.

The Supreme Court's decision in Boynton meant that people traveling between states had the right to ignore local segregation rules. But police in the South still saw the Freedom Riders' actions as illegal. In some places, like Birmingham, Alabama, the police even worked with groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). They allowed these mobs to attack the Riders.

Contents

The Start of the Freedom Rides

Planning the Journey

The idea for the Freedom Rides came from an earlier protest in 1947 called the Journey of Reconciliation. This journey was also meant to test a Supreme Court ruling against racial discrimination on buses. Bayard Rustin and George Houser from CORE helped lead that first journey.

The first Freedom Ride in 1961 began on May 4. It was led by CORE Director James Farmer. Thirteen young Riders, seven Black and six white, started their journey from Washington, D.C. They rode on Greyhound and Trailways buses. Their plan was to travel through several Southern states and end in New Orleans, Louisiana. Many of the Riders were college students, and most were between 18 and 30 years old. They came from many different states and backgrounds. Before the trip, they learned about nonviolent protest methods.

How the Riders Protested

The Freedom Riders had a plan for their journey. At least one Black rider would sit in the front of the bus, where seats were usually reserved for white people. Also, at least one Black and one white rider would sit together. The rest of the group would sit throughout the bus. One rider would follow the segregation rules to avoid arrest. This person would then contact CORE and arrange bail for those who were arrested.

They faced only small problems in Virginia and North Carolina. But John Lewis was attacked in Rock Hill, South Carolina. More than 300 Riders were arrested in places like Charlotte, North Carolina, and Jackson, Mississippi.

Challenges in Alabama

The Riders successfully traveled through Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. But they faced terrible violence in Alabama. Outside Anniston, a white mob attacked and burned one of their buses. The second group of Riders was attacked by Ku Klux Klan members in Birmingham. The city police did not help them.

The Freedom Rides had two important outcomes. First, the U.S. government put pressure on the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC). This group controlled interstate buses and terminals. The ICC then ordered an end to racial segregation in all waiting rooms and lunch counters. This rule started on November 1, 1961. Even though not everyone followed it right away, it sent a clear message. It showed that segregation in other public places would likely end soon.

Continuing the Journey

Leaving Birmingham

After the violence, the Riders decided to fly from Birmingham to New Orleans. They wanted to reach the planned rally there. When they first got on the plane, everyone had to get off because of a bomb threat.

When they arrived in New Orleans, it was hard to find a place for them to stay. So, Norman C. Francis, the president of Xavier University of Louisiana, secretly let them stay in a dorm on campus.

Nashville Students Step Up

Diane Nash, a college student from Nashville and a leader of the Nashville Student Movement, believed the Rides must continue. She thought that if violence stopped the Freedom Rides, the movement would suffer greatly. So, she found new students to continue the rides. On May 17, ten students from Nashville took a bus to Birmingham. There, they were arrested by police chief Bull Connor and put in jail.

The students stayed strong in jail by singing freedom songs. Bull Connor became so frustrated that he drove them to the Tennessee line and dropped them off. He said, "I just couldn't stand their singing." But the students immediately went back to Birmingham.

Into Mississippi Jails

The next day, May 22, more Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery to continue the rides. The Kennedy administration made a deal with the governors of Alabama and Mississippi. The governors agreed that state police would protect the Riders from mobs. In return, the federal government would not stop local police from arresting Riders for breaking segregation laws at bus stations.

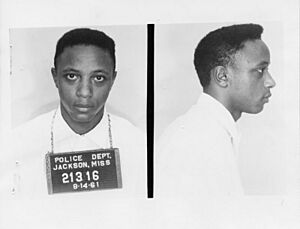

On May 24, Freedom Riders boarded buses for Jackson, Mississippi. Police and the National Guard protected them, and the buses arrived without trouble. But the Riders were arrested right away when they tried to use the white-only facilities at the bus station. This became a pattern for later Freedom Rides. Most Riders traveled to Jackson, where they were arrested and jailed. Their strategy was to fill the jails.

When the jails in Jackson became too full, the state sent the Freedom Riders to the famous Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm. There, they were treated badly. They were put in the Maximum Security Unit, given only underwear, and not allowed to exercise or receive mail. When they kept singing freedom songs, prison officials took away their mattresses, sheets, and toothbrushes. More Freedom Riders arrived from all over the country. At one point, over 300 Riders were held at Parchman Farm.

While in Jackson, the Freedom Riders received help from a local group called Womanpower Unlimited. This group raised money and collected supplies like toiletries, soap, and magazines for the jailed protesters. When Riders were released, Womanpower members offered them places to bathe, clothes, and food. This group was very important to the success of the Freedom Riders.

A Call for Calm

The Kennedy family asked for a "cooling off period." They said the Rides were not patriotic because they made the U.S. look bad during the Cold War. James Farmer, the head of CORE, replied, "We have been cooling off for 350 years, and if we cooled off any more, we'd be in a deep freeze." Other countries, especially the Soviet Union, criticized the U.S. for its racism and the attacks on the Riders.

The international anger about the events put pressure on American leaders. On May 29, 1961, Attorney General Robert Kennedy asked the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to enforce its own ruling from 1955. This ruling had clearly said that "separate but equal" was wrong for interstate bus travel. The ICC had not enforced its own rule before.

More Rides in the Summer

CORE, SNCC, and the SCLC refused to "cool off." They created a Freedom Riders Coordinating Committee to keep the Rides going through the summer. During these months, more than 60 different Freedom Rides traveled across the South. Most of them ended in Jackson, Mississippi, where every Rider was arrested. More than 300 people were arrested in Jackson alone. It is thought that almost 450 people took part in one or more Freedom Rides. About 75% were men, and 75% were under 30 years old. There were about equal numbers of Black and white participants.

During the summer of 1961, Freedom Riders also protested other types of racial discrimination. They sat together in segregated restaurants, lunch counters, and hotels. This was very effective when they targeted large hotel chains. The hotels feared boycotts in the North, so they started to desegregate their businesses.

Tallahassee Protests

In mid-June, a group of Freedom Riders planned to end their ride in Tallahassee, Florida. They were given a police escort to the airport. At the airport, they decided to eat at a restaurant marked "For Whites Only." The owners closed the restaurant rather than serve the mixed group. Even though the restaurant was private, it was leased from the county government. The Riders canceled their plane tickets and waited for the restaurant to reopen. They waited until 11:00 p.m. that night and came back the next day. During this time, angry crowds gathered and threatened violence. On June 16, 1961, the Freedom Riders were arrested in Tallahassee for unlawful assembly.

Ending Segregation and Lasting Impact

New Rules Take Effect

By September, it had been over three months since Robert Kennedy asked the ICC to act. CORE and SNCC leaders planned a large protest in Washington, D.C., to put more pressure on the ICC and the Kennedy administration. But the ICC finally issued the necessary orders just before the end of the month. The new rules started on November 1, 1961.

After the new ICC rule, passengers could sit anywhere they wanted on interstate buses and trains. Signs saying "white" and "colored" were removed from terminals. Segregated drinking fountains, toilets, and waiting rooms were combined. Lunch counters began serving all customers, no matter their race.

The Impact of the Rides

The widespread violence against the Freedom Rides shocked many Americans. Some people worried that the Rides were causing social disorder. White newspapers often criticized the direct action approach taken by CORE. Some national news also showed the Riders as causing trouble.

However, the Freedom Rides also gained a lot of respect from Black and white people across the U.S. They inspired many to take part in direct action for civil rights. Most importantly, the actions of the Freedom Riders from the North, who faced danger for Southern Black citizens, deeply impressed and inspired many Black people in rural areas of the South. These people became the backbone of the wider civil rights movement. They worked on things like voter registration and other activities. Black activists in the South often organized through their churches, which were important centers of their communities.

The Freedom Riders helped inspire people to join later civil rights campaigns. These included voter registration drives across the South, freedom schools, and the Black Power movement. At the time, most Black Southerners could not register to vote. This was because of state laws and practices that had prevented them from voting since the early 1900s. For example, white officials would give reading tests that even highly educated Black people could not pass.

The American Freedom Riders also inspired a similar protest in Australia in 1965. This event, called the Freedom Ride in New South Wales, brought attention to the unfair treatment of Aboriginal Australians in rural areas. They faced segregation in public places and businesses.

List of Freedom Rides

Early Rides

| Ride | Date | Bus Company | Starting Point | Destination | Ref. | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journey of Reconciliation | April 9–23, 1947 | Trailways and Greyhound | Washington, D.C. | Washington, D.C. | ||

| Little Freedom Ride | April 22, 1961 | East St. Louis, Illinois | Sikeston, Missouri |

Main Freedom Rides

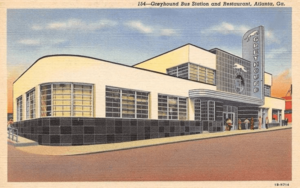

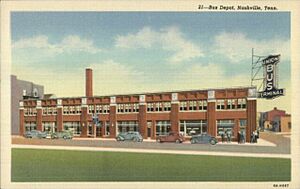

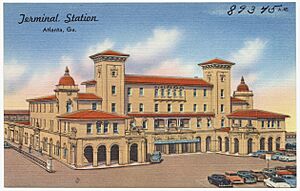

(postcard view, around 1949)

- This means a Freedom Rider tested the rules at a bus or train station only

| Ride | Date | Bus Company or Station | Starting Point | Destination | Ref. | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original CORE Freedom Ride | May 4–17, 1961 | Trailways | Washington, D.C. | New Orleans, Louisiana | ||

| Greyhound | Washington, D.C. | New Orleans, Louisiana | ||||

| Nashville Student Movement Freedom Ride | May 17–21, 1961 | Birmingham, Alabama | New Orleans, Louisiana | |||

| Connecticut Freedom Ride | May 24–25, 1961 | Greyhound | Atlanta, Georgia | Montgomery, Alabama | ||

| Interfaith Freedom Ride | June 13–16, 1961 | Greyhound | Washington, D.C. | Tallahassee, Florida | ||

| Organized Labor–Professional Freedom Ride | June 13–16, 1961 | Washington, D.C. | St. Petersburg, Florida | |||

| Missouri to Louisiana CORE Freedom Ride | July 8–15, 1961 | St. Louis, Missouri | New Orleans, Louisiana | |||

| New Jersey to Arkansas CORE Freedom Ride | July 13–24, 1961 | Newark, New Jersey | Little Rock, Arkansas | |||

| Los Angeles to Houston Freedom Ride | August 9–11, 1961 | Union Railway Station | Los Angeles, California | Houston, Texas | ||

| Monroe Freedom Ride | August 17–September 1, 1961 | Monroe, North Carolina | ||||

| Prayer Pilgrimage Freedom Ride | September 13, 1961 | Trailways | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| Albany Freedom Rides | November 1, 1961 | Trailways (terminal only) | Atlanta, Georgia | |||

| Trailways | Atlanta, Georgia | Albany, Georgia | ||||

| November 22, 1961 | Trailways (terminal only) | Albany, Georgia | ||||

| December 10, 1961 | Central of Georgia Railway | Atlanta Terminal Station | Albany, Georgia (Union Station) | |||

| McComb Freedom Rides | November 29, 1961 | Greyhound | New Orleans, Louisiana | McComb, Mississippi | ||

| December 1, 1961 | Greyhound | Baton Rouge, Louisiana | McComb, Mississippi | |||

| December 2, 1961 | Greyhound | Jackson, Mississippi | McComb, Mississippi | |||

Mississippi Freedom Rides

- This means a Freedom Rider tested the rules at a bus or train station only

| Date | Bus Company or Station | Starting Point | Destination | Ref. | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 24, 1961 | Trailways | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| Greyhound | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| May 28, 1961 | Greyhound | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| Trailways | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| May 30, 1961 | Illinois Central Railroad | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 2, 1961 | Trailways (#1) | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| Trailways (#2) | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| June 6, 1961 | Trailways | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 7, 1961 | Trailways | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| Greyhound Bus Station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | ||||

| Hawkins Field (airport) | St. Louis, Missouri | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| June 8, 1961 | Illinois Central Railroad | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| Hawkins Field (airport) | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| June 9, 1961 | Illinois Central Railroad | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 10, 1961 | Greyhound | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 11, 1961 | Greyhound | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 16, 1961 | Greyhound | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 19, 1961 | Greyhound Bus Station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| June 20, 1961 | Illinois Central Railroad | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 21, 1961 | Trailways | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| June 23, 1961 | Tri-State Trailways station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| June 25, 1961 | Illinois Central Railroad | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 2, 1961 | Trailways | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 5, 1961 | Tri-State Trailways station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| July 6, 1961 | Jackson Union Station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| Greyhound Bus Station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | ||||

| July 7, 1961 | Jackson Union Station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| Trailways | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| July 9, 1961 | Trailways | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| Illinois Central Railroad | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| Tri-State Trailways station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | ||||

| July 15, 1961 | Greyhound | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 16, 1961 | Greyhound | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 21, 1961 | Hawkins Field (airport terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| Greyhound | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| July 23, 1961 | Trailways | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 24, 1961 | Hawkins Field (airport) | Montgomery, Alabama | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 29, 1961 | Greyhound | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 30, 1961 | Illinois Central Railroad | New Orleans, Louisiana | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| July 31, 1961 | Greyhound Bus Station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

| August 5, 1961 | Trailways (bus and terminal) | Nashville, Tennessee | Jackson, Mississippi | ||

| August 13, 1961 | Tri-State Trailways station (terminal only) | Jackson, Mississippi | |||

Remembering the Freedom Riders

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Oprah Winfrey invited all living Freedom Riders to her TV show. This special episode aired on May 4, 2011.

From May 6–16, 2011, 40 college students from across the U.S. took a bus trip. They followed the original route of the Freedom Riders from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. This 2011 Student Freedom Ride was sponsored by PBS. The students met with civil rights leaders and traveled with original Freedom Riders. On May 16, 2011, PBS showed a documentary called Freedom Riders.

In May 2011, the Freedom Rides were remembered in Montgomery, Alabama. This happened at the new Freedom Rides Museum, located in the old Greyhound Bus terminal. This was where some of the violence had taken place in 1961. In February 2013, during a special event, Congressman John Lewis received an apology from the Chief of the Montgomery Police Department. The Chief gave Lewis his own police badge, which made Lewis cry.

In late 2011, activists in Palestine were inspired by the Freedom Riders. They used similar methods in Israel by boarding a bus from which they were excluded.

In January 2017, President Barack Obama declared the Anniston, Alabama bus station a Freedom Riders National Monument.

Freedom Riders in Pop Culture

The 1980s PBS documentary series Eyes on the Prize had an episode about the Freedom Riders. It included an interview with James Farmer.

The title of the 2007 film Freedom Writers is a play on words based on the Freedom Riders. The movie itself mentions the campaign.

PBS also broadcast Freedom Riders in 2012 as part of its American Experience series. It featured interviews and news footage from the movement.

Dan Shore's 2013 opera Freedom Ride, set in New Orleans, celebrates the Freedom Riders.

The TV show The Boondocks aired an episode in 2014 called "Freedom Ride or Die."

The Freedom Riders: The Civil Rights Musical is a musical that tells the story of the Freedom Rides. It was created by Richard Allen and Taran Gray.

Notable Freedom Riders

- Zev Aelony

- James Bevel

- Albert Bigelow

- Malcolm Boyd

- Amos C. Brown

- Gordon Carey

- Stokely Carmichael

- William Sloane Coffin

- Israel S. Dresner

- James Farmer

- Bob Filner

- James Forman

- Tom Hayden

- Mary Hamilton

- William E. Harbour

- Genevieve Hughes

- Bernard Lafayette

- James Lawson

- Frederick Leonard

- John Lewis

- Robert Martinson

- Salynn McCollum

- Charles McDew

- Winonah Myers

- Diane Nash

- Wally Nelson

- James Peck

- Charles Person

- Robert Laughlin Pierson

- John Curtis Raines

- Cordell Reagon

- Meryle Joy Reagon

- Charles Grier Sellers

- Charles Sherrod

- Fred Shuttlesworth

- Carol Ruth Silver

- Helen Singleton

- George Bundy Smith

- Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson

- Peter Sterling

- Daniel N. Stern

- Hank Thomas

- Joan Trumpauer Mulholland

- C. T. Vivian

- Wyatt Tee Walker

- James Zwerg

- Janet Braun-Reinitz

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Viajeros de la libertad para niños

In Spanish: Viajeros de la libertad para niños

- The Freedom Rider, a 1964 album by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, named in honor of the Freedom Riders

- "He Was My Brother", a 1964 Simon & Garfunkel song about the Freedom Riders

- Breach of Peace: Portraits of the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Riders, a 2008 book by Eric Etheridge

- Redlining

- Reverse freedom rides

- Freedom Ride (Australia)

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |