James Forman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Forman

|

|

|---|---|

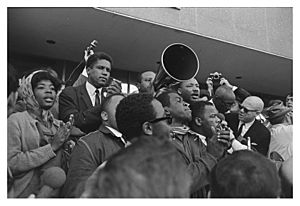

James Forman, second from left, with Martin Luther King Jr. shortly before the final Selma to Montgomery March

|

|

| Born | October 4, 1928 |

| Died | January 10, 2005 (aged 76) Washington, D.C.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Education | St. Anselm's Catholic School |

| Alma mater | Roosevelt University, Cornell University, Union of Experimental Colleges and Universities |

| Known for | Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Black Panther Party |

| Children | 2, including James Forman Jr. |

James Forman (born October 4, 1928 – died January 10, 2005) was an important African-American leader during the Civil Rights Movement. He worked with groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. As the executive secretary of SNCC from 1961 to 1966, Forman helped organize many key events. These included the Freedom Rides, the Albany movement, the Birmingham campaign, and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

After the 1960s, Forman continued to work for social and economic fairness for Black people. He also taught at American University and other schools. He wrote several books about his experiences and ideas. Some of his books are Sammy Younge Jr. (1969), The Making of Black Revolutionaries (1972 and 1997), and Self Determination (1984).

The New York Times newspaper called him "a civil rights pioneer." They said he brought a "fiercely revolutionary vision and masterly organizational skills" to the civil rights battles of the 1960s.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

James Forman was born in Chicago, Illinois, on October 4, 1928. When he was a baby, he went to live with his grandmother, "Mama Jane," on her farm in Marshall County, Mississippi. He grew up in a very poor home. His family did not have electricity or a proper bathroom.

Despite these challenges, Forman said his upbringing helped him succeed. He felt his grandmother taught him about justice. His aunt, who was a teacher, helped him with his studies and gave him an "intellectual fire."

Understanding Racism Early On

Around age six, Forman first experienced racial segregation. He tried to buy a Coca-Cola at a store in Tennessee. He was told he had to drink it in the back, not at the counter. This was the first time he realized that his skin color meant there were "things [he] could and could not do." He also learned that others had the "right" to tell him what he could or could not do.

In 1935, Forman moved to Chicago to live with his mother. He started St. Anselm's Catholic School. Later, he transferred to a public school, Betsy Ross Grammar School. He did so well that he skipped a semester.

From age seven, James sold the Chicago Defender newspaper. Reading these papers helped him develop a "strong sense of protest." He read works by Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. He was greatly influenced by Du Bois, who called for Black people to advance through education. Even before high school, the issue of race was very important to him.

Forman later attended Englewood Technical Prep Academy. He struggled at first but then became an honors student. He was influenced by writers like Richard Wright and Carl Sandburg. He also received military training and was a lieutenant when he graduated in 1947. In an interview, he said he wanted to become a "humanitarian."

After high school, Forman joined the United States Air Force for four years. He later regretted this decision. After his service, he moved to Oakland, California. He saved money to attend the University of Southern California. During his second semester, he was unfairly treated and questioned by police. This was a very difficult experience for him, and he sought help to recover.

Forman returned to Chicago in 1954 and enrolled at Roosevelt University. He became president of the student body and graduated in three years. He then went to graduate school at Boston University. There, he developed ideas for a successful social movement. He believed Black people needed to unite and create a visible movement. He felt it should use nonviolent direct action and involve students in the South. He also believed in strong local leadership, not just one main leader. Before joining SNCC, he taught in Chicago and worked with farmers in Tennessee.

Leading the Way with SNCC

In 1961, Forman joined the new Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced "snick"). He was older and had more experience than most SNCC members. From 1961 to 1966, he helped organize the group. He managed finances, expanded staff, and planned events. Under Forman's leadership, SNCC became a very important group in the Civil Rights Movement.

SNCC started as a partner to Martin Luther King Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Sometimes, Forman's more direct style of activism differed from King's peaceful approach.

In August 1961, Forman was jailed with other Freedom Riders. They were protesting segregated facilities in Monroe, North Carolina. This event connected him with Robert F. Williams, whom Forman admired. They discussed the idea of using self-defense against white oppression. After his release, Forman became SNCC's executive secretary.

Forman sometimes questioned Dr. King's leadership. He worried that King's top-down style might prevent local movements from growing. For example, when King joined the Albany Movement, Forman felt it might take away from local leaders. He believed King's presence "would detract from, rather than intensify," the focus on local people. Forman shared concerns that relying too much on one leader could be risky for the movement.

In an interview, Forman said SNCC was a movement that had "room for intellectuals."

Years before the famous Selma marches of 1965, Forman and other SNCC organizers visited Selma. They helped Amelia Boynton and J. L. Chestnut with voter registration. Forman also helped bring celebrities like James Baldwin and Dick Gregory to Selma. This was for the city's first "Freedom Day" in October 1963. On this day, many African Americans tried to register to vote in a segregated area.

Forman also worked to connect SNCC with the cultural community. He asked folk singer Bob Dylan to perform at SNCC benefits and rallies. One of these rallies in Mississippi appeared in the documentary Don't Look Back. When Dylan received an award, he said the honor truly belonged to "James Forman and SNCC."

Key Protests: Selma and Montgomery

After the second march out of Selma was turned around by Martin Luther King, students from Tuskegee Institute decided to march to the Alabama State Capitol. They wanted to deliver a petition to Governor George Wallace. Forman and many SNCC staff from Selma quickly joined them. SNCC members were eager to take a separate path after the "turnaround Tuesday" event.

On March 11, SNCC started protests in Montgomery and asked others to join. James Bevel, a leader from SCLC, followed them and tried to stop their activities. This caused a disagreement between SCLC and SNCC. Bevel accused Forman of trying to pull people away from the Selma campaign. Forman accused Bevel of creating problems between the student movement and local Black churches. Their argument ended when both were arrested.

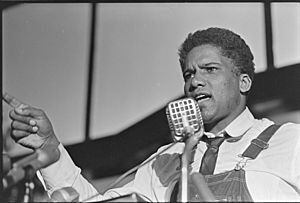

On March 15 and 16, SNCC led hundreds of protesters near the capitol. These included students and local adults. The Montgomery County sheriff's group on horseback met them and drove them back. Some protesters threw things at the police. At a meeting on March 16, Forman strongly demanded that the President protect demonstrators. He warned, "If we can't sit at the table of democracy, we'll knock the [...] legs off."

The New York Times reported on the Montgomery events on its front page. Dr. King was concerned by Forman's strong words. However, he joined Forman in leading a march of 2000 people to the Montgomery County courthouse.

According to historian Gary May, Montgomery officials apologized for the attack on SNCC protesters. They invited King and Forman to discuss future protests. In these talks, officials agreed to stop using the county group against protesters. They also agreed to issue march permits to Black people for the first time.

After SNCC Work

After Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson became executive secretary, Forman remained involved with SNCC. He helped with a planned partnership between SNCC and the Black Panther Party in 1967. He even held a leadership role in the Panthers for a short time. In 1969, after the partnership failed, Forman worked with other Black political groups. In Detroit, he took part in the Black Economic Development Conference. There, his Black Manifesto was approved. He also started a group called the Unemployment and Poverty Action Committee.

As part of his "Black Manifesto", Forman interrupted church services in May 1969. He went to New York City's Riverside Church. He demanded $500 million in payments from white churches. He said this money was to make up for the unfair treatment African Americans had faced. The church's minister called the demands "exorbitant." However, he agreed with the idea behind them. Later, the church decided to give a part of its yearly income to anti-poverty efforts.

On May 30, 1969, Forman planned to do something similar at a Jewish Synagogue. A group called the Jewish Defense League protested his plans. Forman did not show up at the synagogue.

Later Life and Passing

During the 1970s and 1980s, Forman studied at Cornell University. He focused on African and African-American Studies. In 1982, he earned a Ph.D. from the Union of Experimental Colleges and Universities.

Forman spent the rest of his life organizing Black people and those without power. He worked on issues of economic and social fairness. He also taught at American University in Washington, D.C.. He wrote several books about his experiences and ideas. These included Sammy Younge Jr. (1969), The Making of Black Revolutionaries (1972 and 1997), and Self Determination (1984).

Forman passed away on January 10, 2005, from colon cancer. He was 76 years old. He died at a hospice in Washington, DC.

Personal Life

James Forman had two sons, Chaka Forman and James Forman Jr.. James Forman Jr. is now a professor at Yale Law School.

His Beliefs

In his autobiography, The Making Of Black Revolutionaries, Forman wrote about his atheism. He believed that "belief in God hurts my people." In 1994, he received the African American Humanist Award.

See also

In Spanish: James Forman para niños

In Spanish: James Forman para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |