James Baldwin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Baldwin

|

|

|---|---|

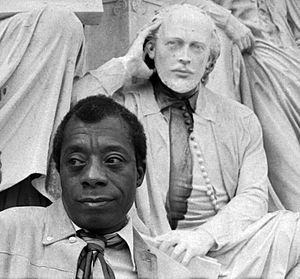

Baldwin in 1969

|

|

| Born | James Arthur Jones August 2, 1924 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | December 1, 1987 (aged 63) Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France |

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery, Westchester County, New York |

| Occupation | Writer, activist |

| Education | DeWitt Clinton High School |

| Genre |

|

| Years active | 1947–1985 |

| Notable works |

|

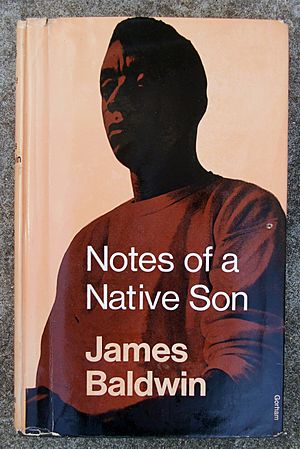

James Arthur Baldwin (born August 2, 1924 – died December 1, 1987) was an important African American writer. He was known for his essays, novels, plays, and poems. His first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, came out in 1953. Years later, Time magazine called it one of the 100 best English novels from 1923 to 2005. His first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son, was published in 1955.

Baldwin's stories often explored personal challenges and social pressures. He wrote about themes like race and social class. His work often showed the big changes happening in America in the mid-1900s, like the Civil Rights Movement. Many of his characters were African American. They often faced difficulties as they tried to find their place in society and accept themselves. His novel Giovanni's Room, written in 1956, is a good example of these themes.

Even after his death, Baldwin's work remains popular. Some of his writings have been made into movies. For example, an unfinished book, Remember This House, became the documentary film I Am Not Your Negro (2016). This film was nominated for an Oscar. His novel If Beale Street Could Talk was also made into an award-winning film in 2018.

Besides writing, James Baldwin was also a well-known public speaker. He was especially active during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

James Arthur Jones was born on August 2, 1924, in Harlem Hospital in New York City. His mother, Emma Berdis Jones, raised him as a single parent. She had moved to Harlem from Maryland when she was 19. Many African Americans like her moved north during the Great Migration to escape racial segregation in the South.

In 1927, Emma married David Baldwin, a laborer and preacher. James took his stepfather's last name. Emma and David had eight more children together. James rarely spoke about his mother, but he admired and loved her. The family moved several times within Harlem. Harlem was a diverse area, but many families faced poverty.

James had a difficult relationship with his stepfather, David Sr. David Sr. was much older and had been born before slavery ended. He often disagreed with James, especially about his love for books and movies. David Sr. also had strong feelings about white people. He died in 1943 when James was 19. James later wrote about his stepfather in his essay "Notes of a Native Son", understanding that his father loved his children in his own way.

As the oldest child, James worked part-time to help his family. He saw the struggles of poverty and unfair treatment around him. He once wrote that he felt he "never had a childhood."

School Days and Public Speaking

James Baldwin started school at Public School 24 in Harlem. The principal, Gertrude E. Ayer, was the city's first Black principal. She saw James's talent and encouraged his writing. His teachers also supported him. By fifth grade, James had already read many classic books. He even won a prize for a short story published in a church newspaper.

At P.S. 24, James met Orilla "Bill" Miller, a white teacher who helped him see beyond racial differences. She took him to see a play, which sparked his dream of becoming a playwright.

Later, at Frederick Douglass Junior High School, James met two more important people. Herman W. "Bill" Porter, a Harvard graduate, was the advisor for the school newspaper. James became the editor and published his first essay, "Harlem—Then and Now." He also met Countee Cullen, a famous poet from the Harlem Renaissance. Cullen taught French and inspired James's dream of living in France. James graduated in 1938.

In 1938, James went to De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx. This school was mostly white and Jewish. There, he worked on the school's magazine, the Magpie, with future famous people like photographer Richard Avedon. He published poems and other writings. When he graduated in 1941, his yearbook said his goal was to be a "novelist-playwright."

During high school, James found comfort in religion. He started preaching at a Pentecostal church at age 14. This experience taught him how to speak powerfully to a crowd. He gave his last sermon in 1941. He later wrote that the church "was a mask for self-hatred and despair." His stepfather once asked him, "You'd rather write than preach, wouldn't you?"

Life in New York After School

After high school, James left school in 1941 to help his family earn money. He took various jobs, like helping to build a U.S. Army depot in New Jersey. In New Jersey, he experienced strong prejudice from white co-workers. He felt frustrated and angry by this unfair treatment.

In one incident, he was denied service at a restaurant because he was Black. This made him so angry that he threw a water mug, which shattered a mirror. He and his friend had to quickly leave. These experiences made him want to leave America later.

James struggled between his desire to write and his need to support his family. He feared becoming like his stepfather, who had trouble providing for his family. He lost several jobs and felt lost.

Then, he met Beauford Delaney, a painter, in Greenwich Village. Delaney became a mentor and friend, showing James that a Black man could make a living through art. James moved to Greenwich Village, a place that fascinated him. He worked at a restaurant and met many prominent Black people there.

Around 1944, James met Richard Wright, a famous writer. Wright liked James's early manuscript for Go Tell It On The Mountain and encouraged his editors to consider it. Although the book wasn't published right away, James continued to send letters to Wright.

In Greenwich Village, James connected with many literary figures. He wrote reviews for The New Leader and published his first essay, "The Harlem Ghetto," in Commentary magazine in 1948. This essay explored how Harlem was a reflection of white America. His second essay, "Journey to Atlanta," was also well-received.

Career Highlights

Life in Paris (1948–1957)

Feeling disappointed by the prejudice in America, James Baldwin left the United States in 1948 at age 24. He moved to Paris, France, wanting to see himself and his writing in a new way.

In Paris, Baldwin became part of the lively cultural scene. He started publishing his work in literary magazines. He lived in Paris for nine years, mostly in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, and also traveled to Switzerland and Spain. He was often poor during this time.

He met many artists and writers, including Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. He also met Lucien Happersberger, a young Swiss man who became his close friend. Living in Paris helped Baldwin escape the daily unfairness of racism he faced in America.

During his early years in Paris, Baldwin wrote several important works. He explored the differences between Black Americans and Black Africans in Paris in "The Negro in Paris." He also wrote "The Preservation of Innocence," about violence against homosexuals. In 1949, he was arrested in Paris by mistake. He wrote about this experience in his essay "Equal in Paris," where he realized that in France, he was seen simply as an American, not just a Black man.

Baldwin also wrote critiques of Richard Wright's work, arguing against "protest literature" that he felt limited human experience. These essays made him known as a promising young Black writer.

In 1951, Baldwin visited a village in Switzerland. He wrote about his experiences there in "Stranger in the Village" (1953). He described how the Swiss villagers, who had little experience with Black people, treated him in ways that showed their lack of understanding. He reflected on how the history between Black and white Americans had created a complex relationship that was different from what he found in Europe.

In 1953, his friend Beauford Delaney came to France, which was a very important event for Baldwin. Around this time, Baldwin also became friends with many other Black American artists living in Paris, including Maya Angelou. In 1954, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship and published his play The Amen Corner. He returned to Paris in 1955.

Baldwin decided to return to the United States in 1957. He spent his last year in France enjoying his time and preparing for the publication of Giovanni's Room.

Literary Achievements

Baldwin's first published work was a review of writer Maxim Gorky in The Nation magazine in 1947. He continued to write for this magazine throughout his life.

1950s Works

In 1953, Baldwin's first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, was published. This book was partly based on his own life. He started writing it when he was 17. Two years later, his first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son, came out. He continued to write different types of works, including poetry and plays.

His second novel, Giovanni's Room, published in 1956, caused some discussion. People expected him to write only about African American experiences, but Giovanni's Room mainly featured white characters.

Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953)

Baldwin sent the manuscript for Go Tell It on the Mountain from Paris to a New York publisher in 1952. He sailed back to the U.S. to finalize the book's terms. He spent time with his family, whom he hadn't seen in nearly three years. He agreed to rewrite parts of the novel for an advance payment. The book was published in May 1953.

In Go Tell It on the Mountain, Baldwin wanted to show the rich traditions and experiences of Black life. He believed that earlier "protest literature" had not fully captured this.

Giovanni's Room (1956)

Soon after returning to Paris, Baldwin learned that Giovanni's Room had been accepted for publication. He sent the final manuscript in April 1956, and the book was published that autumn. The reviews for Giovanni's Room were positive.

Return to New York

Even in Paris, Baldwin heard about the growing Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. He was deeply affected by events like the murder of Emmett Till in 1955 and Rosa Parks's arrest in 1955. He felt he was wasting time in Paris and decided to return to the U.S. in 1957.

He wrote essays about American racism, including "The Crusade of Indignation" and "William Faulkner and Desegregation." He wanted to finish his novel Another Country before leaving, but decided to go back sooner. He sailed for New York in July 1957.

1960s Works

Baldwin's novels Another Country (1962) and Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone (1968) were experimental. They featured both Black and white characters.

His long essay "Down at the Cross," which became the book The Fire Next Time (1963), showed the anger and changes of the 1960s. This essay was first published in The New Yorker. It made Baldwin famous and he appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1963. He toured the South, speaking about the Civil Rights Movement.

Baldwin became a well-known voice for civil rights. He often appeared on television and gave speeches. The essay discussed the relationship between Christianity and the Black Muslim movement. Some Black nationalists criticized Baldwin for his message of love. White readers sought answers in his book about what Black Americans truly wanted. Baldwin's essays clearly expressed the anger and frustration of Black Americans.

1970s and 1980s Works

Baldwin's next essay collection, No Name in the Street (1972), talked about his own experiences in the late 1960s. It included his thoughts on the assassinations of his friends: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr..

His writings from the 1970s and 1980s were not as widely recognized at first, but they have gained more attention recently. Some of his essays and interviews from the 1980s openly discussed homophobia. His novels from the 1970s, If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) and Just Above My Head (1979), highlighted the importance of Black American families. He also published a book of poetry, Jimmy's Blues (1983), and another essay collection, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985).

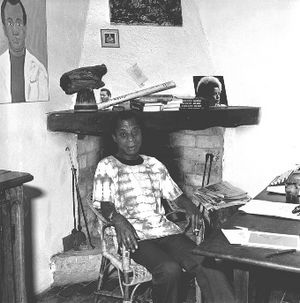

Life in Saint-Paul-de-Vence

Baldwin lived in France for most of his later life, settling in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in southern France in 1970. His home was always open to friends visiting the French Riviera. Painter Beauford Delaney often stayed there and painted portraits of Baldwin. Actors Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier were also frequent guests.

Many of Baldwin's musician friends, like Nina Simone and Miles Davis, visited during jazz festivals. Baldwin learned to speak French fluently and became friends with French actor Yves Montand and writer Marguerite Yourcenar.

He spent his days writing and answering mail from around the world. He wrote several of his last books in his Saint-Paul-de-Vence home, including Just Above My Head (1979) and Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985). He also wrote his famous "Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis" there in 1970.

Death

James Baldwin died from stomach cancer on December 1, 1987, in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France. He was buried at the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, near New York City.

At the time of his death, Baldwin was working on an unfinished book called Remember This House. This book was a memoir of his memories of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. This manuscript later became the basis for the 2016 documentary film I Am Not Your Negro.

After his death, there was a legal discussion about the ownership of his home in France. His house, known as "Chez Baldwin," has become a focus for scholarly work and activism. The National Museum of African American History and Culture has an online exhibit about his historic French home.

Sadly, despite efforts to save it and turn it into an artist residency, Baldwin's house was eventually torn down in 2019 to build an apartment complex.

Social and Political Activism

Baldwin returned to the United States in 1957 when the civil rights laws were being discussed. He was deeply moved by a photo of a young girl, Dorothy Counts, facing an angry crowd to desegregate schools. He was asked to report on what was happening in the American South. He visited places like Charlotte, North Carolina, where he met Martin Luther King Jr., and Montgomery, Alabama. He wrote two essays about his experiences.

He wrote many articles about the movement for various magazines. In 1962, he published "Down at the Cross," which became The Fire Next Time.

Baldwin supported groups like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Joining CORE allowed him to travel across the South, giving speeches about racial inequality. He had a unique view of the racial problems in both the North and South.

In 1963, he went on a lecture tour in the South, speaking to students and others about his ideas on race. His views were between the strong approach of Malcolm X and the nonviolent approach of Martin Luther King, Jr.

By spring 1963, the media recognized Baldwin's clear analysis of white racism and his powerful descriptions of the pain felt by Black Americans. Time magazine featured him on its cover.

During the crisis in Birmingham, Alabama, Baldwin contacted Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. He blamed the violence on the lack of action from leaders. Kennedy invited Baldwin to a meeting in New York with other important figures like Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne. This meeting helped bring attention to civil rights as a moral issue.

The FBI kept a large file on James Baldwin, collecting many pages of documents about him from 1960 to the early 1970s.

Baldwin also took part in the famous March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, with friends like Sidney Poitier and Marlon Brando.

After a church bombing in Birmingham, Baldwin called for widespread civil disobedience. He traveled to Selma, Alabama, where he saw people trying to register to vote, facing armed officers. He spoke in a church, blaming Washington for not acting. In March 1965, Baldwin joined marchers walking from Selma to Montgomery, protected by federal troops.

However, he did not like being called a "civil rights activist." He agreed with Malcolm X that if someone is a citizen, they should not have to fight for their basic rights. He saw the movement as a "very peculiar revolution" that aimed to change American life for everyone. In a 1979 speech, he called it "the latest slave rebellion."

In 1968, Baldwin signed a pledge to refuse to pay income tax to protest the Vietnam War.

Inspiration and Friendships

A big influence on Baldwin was the painter Beauford Delaney.

Later, Richard Wright supported him. Baldwin called Wright "the greatest black writer in the world." Wright helped Baldwin get an award. Baldwin's essay "Notes of a Native Son" and his book Notes of a Native Son refer to Wright's novel Native Son. However, in his 1949 essay "Everybody's Protest Novel," Baldwin criticized Native Son for not having believable characters. This ended their close friendship, though Baldwin later said he loved Wright and was trying to understand things for himself.

In 1965, Baldwin debated William F. Buckley Jr. at Cambridge Union in the UK. The topic was whether the American Dream had been achieved at the expense of African Americans. Baldwin won the vote by a large margin.

In 1949, Baldwin met Lucien Happersberger, who remained his friend until Baldwin's death.

Baldwin was also a close friend of singer and activist Nina Simone. He, along with Langston Hughes and Lorraine Hansberry, helped Simone learn about the Civil Rights Movement. Baldwin and Hansberry also met with Robert F. Kennedy, along with Kenneth Clark and Lena Horne, to discuss civil rights laws.

Baldwin influenced French painter Philippe Derome. He also knew many other famous people, including Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Miles Davis, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Maya Angelou. He wrote about his relationship with Malcolm X. He worked with his childhood friend Richard Avedon on the 1964 book Nothing Personal.

Maya Angelou called Baldwin her "friend and brother" and said he helped set the stage for her autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The French government honored Baldwin with the Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur in 1986.

Baldwin was also a close friend of Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison. After his death, Morrison wrote a tribute to Baldwin in The New York Times, calling him her literary inspiration.

Honors and Awards

- Guggenheim Fellowship, 1954

- Eugene F. Saxton Memorial Trust Award

- Foreign Drama Critics Award

- George Polk Memorial Award, 1963

- MacDowell fellowships: 1954, 1958, 1960

- Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur, 1986

Works

Novels

- 1953. Go Tell It on the Mountain (partly based on his own life)

- 1956. Giovanni's Room

- 1962. Another Country

- 1968. Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone

- 1974. If Beale Street Could Talk

- 1979. Just Above My Head

Essays and Short Stories

Many of Baldwin's essays and short stories were first published in collections. Others were published alone and later included in his books. Some examples include:

- 1949. "Everybody's Protest Novel". Partisan Review

- 1953. "Stranger in the Village". Harper's Magazine.

- 1957. "Sonny's Blues". Partisan Review.

- 1962. "Letter from a Region of My Mind". The New Yorker.

- 1963. "A Talk to Teachers"

- 1976. The Devil Finds Work – a book-length essay.

Collections

These collections included new and older essays and short stories:

- 1955. Notes of a Native Son

- 1961. Nobody Knows My Name: More Notes of a Native Son

- 1963. The Fire Next Time

- 1965. Going to Meet the Man

- 1972. No Name in the Street

- 1983. Jimmy's Blues

- 1985. The Evidence of Things Not Seen

- 1985. The Price of the Ticket

Plays

- 1954 The Amen Corner

- 1964. Blues for Mister Charlie

Collaborative Works

- 1964. Nothing Personal, with Richard Avedon (photography)

- 1971. A Rap on Race, with Margaret Mead

- 1973. A Dialogue, with Nikki Giovanni

- 1976. Little Man Little Man: A Story of Childhood, with Yoran Cazac

Media Appearances

- 1963. "A Conversation With James Baldwin", a TV interview by WGBH.

- 1963. Take This Hammer, a TV documentary about Black people in San Francisco.

- 1965. "Debate: Baldwin vs. Buckley", a TV special from the BBC featuring a debate at Cambridge University.

- 1971. Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris. Documentary.

- 1975. "Assignment America; 119; Conversation with a Native Son", a TV conversation between Baldwin and Maya Angelou.

See also

In Spanish: James Baldwin para niños

In Spanish: James Baldwin para niños

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of American novelists

Images for kids

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |