Dorothy Counts facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Dorothy Counts

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | March 25, 1942 |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Civil rights activism |

Dorothy "Dot" Counts-Scoggins was born on March 25, 1942. She is an important American civil rights leader. She was one of the first Black students to attend Harry P. Harding High School.

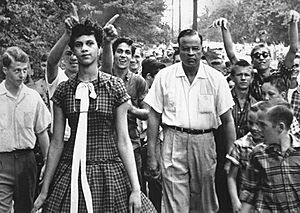

After just four days, her parents took her out of the school because she was being treated badly. Pictures of Dorothy being yelled at by other students were seen all over the world. These images helped show how unfair things were during that time.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Dorothy Counts-Scoggins was born in Charlotte, North Carolina. She grew up near Johnson C. Smith University, where both her parents worked. She was the only daughter among four children.

Her father, Herman L. Counts Sr., was a professor who taught about ideas and beliefs at the university. Her mother, Olethea Counts, took care of their home and later managed a student dorm. Education was very important in Dorothy's family. Many of her aunts and uncles were teachers. Because she was the only girl, her three brothers and parents often looked out for her.

Going to Harry P. Harding High School

In 1956, many Black students in North Carolina wanted to transfer to schools that were only for white students. This happened after a plan called the Pearsall Plan was passed. Dorothy's father was asked by Kelly Alexander Sr. if his children would like to try. Dorothy and two of her brothers applied to attend a white school. Only Dorothy was accepted.

On September 4, 1957, when Dorothy was 15, she was one of four Black students who started at all-white schools in the area. She went to Harry P. Harding High School in Charlotte, North Carolina. The other three students went to different schools nearby.

First Day at Harding High

Dorothy's father and a family friend, Edwin Thompkins, dropped her off on her first day. Their car couldn't get close to the school entrance. Edwin offered to walk Dorothy to the front while her father parked. As she got out of the car, her father told her, "Hold your head high. You are inferior to no one."

About 200 to 300 people, mostly students, were in the crowd. A woman encouraged the students to stop Dorothy and even to spit on her. Dorothy walked past without reacting. She later told reporters that people threw rocks at her, but they mostly landed in front of her. Students formed walls to block her but moved at the last second to let her pass. A photographer named Douglas Martin took a famous picture of Dorothy being teased. This photo won an award in 1957.

Inside the school, Dorothy went to the auditorium. She heard many mean words shouted at her. She said no adults helped or protected her. When she went to her homeroom to get her books, she was ignored. At noon, her parents asked if she wanted to keep going to the school. Dorothy said yes, hoping things would get better once students got to know her.

Challenges and a Friend

Dorothy felt sick the next day and stayed home. She returned to school on Monday. This time, there was no crowd outside. However, students and teachers were surprised she came back and continued to treat her badly. In class, she was placed at the back and ignored by her teacher.

On Tuesday, during lunch, a group of boys surrounded her and spat in her food. She went outside and met another new student from her homeroom. This girl talked to Dorothy about being new to Charlotte. When Dorothy went home, she told her parents she felt better because she had made a friend. After what happened at lunch, Dorothy asked her parents to pick her up to eat lunch outside the school.

On Wednesday, Dorothy saw the young girl in the hallway, but the girl ignored her and looked down. During lunch that day, someone threw a blackboard eraser at Dorothy, hitting the back of her head. As she went outside to meet her oldest brother for lunch, she saw a crowd around her family's car. The back windows were broken. Dorothy said this was the first time she felt truly scared, because now her family was being attacked.

Leaving Harding High

Dorothy told her family what happened. Her father called the school leader and the police. The school leader said he didn't know what was going on at the school. The police chief said they couldn't promise Dorothy would be safe. After these calls, her father decided to take her out of the high school. He said in a statement: "It is with compassion for our native land and love for our daughter Dorothy that we withdraw her as a student at Harding High School. As long as we felt she could be protected from bodily injury and insults within the school's walls and upon the school premises, we were willing to grant her desire to study at Harding."

Life After Harding High

Because of her experience, Dorothy's parents wanted her to go to a school where Black and white students learned together. They didn't want her to think all white people were the same. She went to live with her aunt and uncle in Yeadon, Pennsylvania, to finish her sophomore year. She attended a public school there that had students of all races. Her aunt and uncle talked to the principal about Dorothy's past. A meeting was held with students and teachers to make sure Dorothy would be treated well. Dorothy didn't know about this meeting until later.

Her time in Yeadon was good, but she missed home. So, after her sophomore year, she went to Allen School, a private school for girls in Asheville, North Carolina. This school did not have students of all races, but the teachers were from different backgrounds. Dorothy graduated from Allen School. She then returned to Charlotte and attended Johnson C. Smith University, where she earned a degree in Psychology in 1964. In 1962, she joined the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.

After college, Dorothy moved to New York. She worked with children who had been hurt or neglected. Later, she moved back to Charlotte. There, she worked for non-profit groups that helped children from low-income families. She is still involved with her college and works to protect the history of Beatties Ford Road.

Recognition and Legacy

In 2006, Dorothy Counts-Scoggins received an email from a man named Woody Cooper. He admitted he was one of the boys in the famous picture and wanted to say sorry. They met for lunch, and Cooper asked for her forgiveness.

They decided to share their story together and gave many interviews. In 2008, Dorothy Counts-Scoggins and seven other people were honored for helping to integrate North Carolina's public schools. Each person received an award from Governor Mike Easley. In 2010, Harding High School renamed its library in honor of Dorothy Counts-Scoggins. This is a special honor, especially for someone who is still living.

In a 2016 Netflix documentary called I Am Not Your Negro, writer James Baldwin remembered seeing photos of Dorothy Counts-Scoggins. He wrote that it made him "furious and filled me with both hatred and pity and it made me ashamed—One of us should have been there with her."

See also

In Spanish: Dorothy Counts para niños

In Spanish: Dorothy Counts para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |