William F. Buckley Jr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William F. Buckley Jr.

|

|

|---|---|

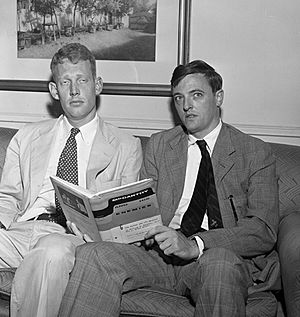

Buckley in an undated handout photograph

|

|

| Born | William Francis Buckley November 24, 1925 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | February 27, 2008 (aged 82) Stamford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | Yale University (BA) |

| Subject |

|

| Spouse |

Patricia Taylor Buckley

(m. 1950; died 2007) |

| Children | Christopher |

| Relatives |

|

| Military career | |

| Service/ |

United States Army |

| Years of service | 1944–1946 |

| Rank | First lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

William F. Buckley Jr. (born William Francis Buckley; November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American writer, thinker, and political commentator. He is known for starting the magazine National Review in 1955. This magazine helped shape the conservative movement in the United States during the mid-1900s.

Buckley also hosted a TV show called Firing Line from 1966 to 1999. It was the longest-running public affairs show with one host in American TV history. He was famous for his unique way of speaking and his large vocabulary.

Born in New York City, Buckley served in the United States Army during World War II. After the war, he studied at Yale University. He was very active in debates and wrote about conservative politics. He also worked for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for two years. Besides his work at National Review, Buckley wrote over fifty books. These books covered many topics like writing, speaking, history, politics, and sailing. He even wrote a series of novels about a fictional CIA agent named Blackford Oakes.

Buckley called himself both a conservative and a libertarian. A historian named George H. Nash said in 2008 that Buckley was "arguably the most important public intellectual in the United States in the past half century." He was seen as the main voice of American conservatism for a whole generation.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

William F. Buckley Jr. was born on November 24, 1925, in New York City. His parents were Aloise Josephine Antonia (Steiner) and William Frank Buckley Sr.. His father was a lawyer and oil developer from Texas. His mother was from New Orleans and had Swiss-German, German, and Irish roots. His grandparents on his father's side were Irish and from Canada.

William was the sixth of ten children. As a boy, his family moved to Mexico, then to Sharon, Connecticut. He started school in Paris, France, where he attended first grade. By age seven, he learned English formally in London. His first languages were Spanish and French.

As a child, Buckley loved music, sailing, horses, hunting, and skiing. These interests showed up in his later writings. He was taught at home until eighth grade using a special curriculum. Just before World War II, when he was 12 or 13, he went to a Jesuit school in England called St John's Beaumont.

Family Connections and Influences

Buckley's father, William Sr., made his money in oil in Mexico. He was important in Mexican politics for a time. William Jr. had nine brothers and sisters. Many of them also became writers or were involved in conservative causes. His brother James L. Buckley became a U.S. Senator from New York.

During World War II, Buckley's family took in Alistair Horne, who later became a famous British historian. They stayed friends for life. Both attended the Millbrook School in Millbrook, New York, and graduated in 1943. At Millbrook, Buckley started and edited the school's yearbook, The Tamarack. This was his first experience in publishing.

A libertarian writer named Albert Jay Nock often visited the Buckley family home. William F. Buckley Sr. encouraged his son to read Nock's books. One of Nock's famous books was Our Enemy, the State.

Love for Music

When he was young, Buckley became very good at music. He played the harpsichord well, calling it "the instrument I love beyond all others." He was also a skilled pianist. He even appeared on a radio show called Piano Jazz. Buckley greatly admired Johann Sebastian Bach and wanted Bach's music played at his funeral.

Religious Beliefs

Buckley was raised Catholic and was a member of the Knights of Malta. He said his family was very firm in their religious faith. When he went to Millbrook School, he was allowed to attend Catholic Mass even though the school was Protestant. As a young person, he felt there was some anti-Catholic bias in the U.S.

When his first book, God and Man at Yale, came out in 1951, some critics said his Catholic views made his writing biased. However, Buckley remained a strong Catholic throughout his life. He regularly attended the Tridentine Mass.

Education and Military Service

Buckley attended the National Autonomous University of Mexico until 1943. The next year, he joined the United States Army. He became a second lieutenant. He served in the U.S. throughout the war.

After the war ended in 1945, Buckley went to Yale University. He joined the secret Skull and Bones society and was an excellent debater. He was active in the Conservative Party of the Yale Political Union. He also worked as chairman of the Yale Daily News and shared information with the FBI. At Yale, Buckley studied political science, history, and economics. He graduated with honors in 1950.

Working for the CIA

Buckley taught Spanish at Yale from 1947 to 1951. Then, he was recruited into the CIA, like many other Ivy League graduates at that time. He worked for the CIA for two years. One year was spent in Mexico City, where he worked on political actions for E. Howard Hunt. Buckley and Hunt remained friends for life.

After leaving the CIA, he worked as an editor at The American Mercury in 1952. However, he left because he felt the magazine was becoming anti-Semitic.

Marriage and Family Life

In 1950, Buckley married Patricia Aldyen Austin (Pat) Taylor (1926–2007). She was the daughter of a Canadian businessman. Patricia was a student at Vassar College when they met. She became known for raising money for charities, including hospitals. She also raised money for Vietnam War veterans. Pat Buckley passed away in 2007 at age 80 after a long illness. Friends said Buckley seemed very sad after her death.

William and Patricia Buckley had one son, Christopher Buckley, who is also an author. They lived in Stamford, Connecticut, and had an apartment in Manhattan. For over thirty years, they also spent six to seven weeks each year living and working in Rougemont, Switzerland.

First Books and Ideas

Critiquing Yale University

Buckley's first book, God and Man at Yale, was published in 1951. In the book, he criticized Yale University, saying it had moved away from its original goals. Some critics felt he misunderstood the idea of academic freedom. A Yale graduate named McGeorge Bundy wrote that the book was "dishonest in its use of facts, false in its theory, and a discredit to its author."

Buckley believed the book got a lot of attention because of its "Introduction" by journalist John Chamberlain. He said it "changed the course of his life."

Defending Senator McCarthy

In 1954, Buckley and his brother-in-law L. Brent Bozell Jr. wrote a book together called McCarthy and His Enemies. This book defended Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy was known for his strong actions against communism. Buckley and Bozell said McCarthy was a patriotic person fighting communism. They admitted he sometimes "exaggerated" but believed his cause was right.

National Review Magazine

Buckley started National Review magazine in 1955. At that time, there were not many publications for conservative ideas. He was the magazine's editor-in-chief until 1990. During this time, National Review became the most important magazine for American conservatism. It brought together different types of conservatives and libertarians.

Buckley invited many smart people to write for National Review. Some of them were former Communists or people who had worked on the far Left. These included Whittaker Chambers and James Burnham.

Shaping Conservative Ideas

Buckley and his editors used National Review to decide what counted as "conservative." They spoke out against people or groups they felt were not truly conservative. For example, Buckley criticized Ayn Rand, the John Birch Society, and people who supported racism or anti-Semitism.

He felt that Ayn Rand's ideas were not compatible with his understanding of conservatism, especially her views on religion. He also strongly criticized Robert W. Welch Jr. and the John Birch Society in 1962, calling their ideas "far removed from common sense." He urged the Republican Party to distance itself from Welch's influence.

The Buckley Rule

The "Buckley rule" is a famous idea from William F. Buckley Jr. It states that National Review would "support the rightwardmost viable candidate" for a political office. Buckley first used this rule during the 1964 Republican primary election. This meant supporting a candidate who shared their conservative views and could help the conservative movement grow.

Political Views and Actions

Supporting Political Candidates

In 1963–64, Buckley helped gather support for Senator Barry Goldwater's presidential campaign. He used National Review to help Goldwater get the Republican nomination and then run for president.

In 1971, Buckley brought together a group of conservatives to discuss their concerns about some of Richard Nixon's policies. They opposed Nixon's welfare plan and his efforts to improve relations with the Soviet Union and China. Buckley, as a strong anti-communist, disagreed with these foreign policy moves. The group, called the Manhattan Twelve, publicly announced they would no longer support Nixon. However, in 1973, the Nixon Administration appointed Buckley as a delegate to the United Nations.

In 1973, Buckley supported Ronald Reagan's presidential campaign against President Gerald Ford. In 1981, Buckley told President-elect Reagan that he would not accept any official position. Reagan jokingly said he wanted to make Buckley ambassador to Afghanistan.

Views on Race and Segregation

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Buckley did not support federal civil rights laws. He also supported racial segregation in the South for a time. In 1957, he wrote an editorial called "Why the South Must Prevail." He argued that temporary segregation was needed in the South. He believed this was because the black population lacked the education and economic development for immediate racial equality. He said white Southerners had "the right to impose superior mores."

Buckley visited South Africa in the 1960s and wrote about its policy of apartheid, which was a system of racial segregation. He tried to explain apartheid and said it was "a sincere people's effort to fashion the land of peace they want so badly."

However, over time, Buckley's views on civil rights changed. He began to criticize practices that stopped African Americans from voting. He also condemned businesses that refused service to African Americans after the 1964 Civil Rights Act. A turning point for him was the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963, which killed four African American girls. A biographer said Buckley was very upset by this event.

He later said he wished National Review had supported civil rights laws more in the 1960s. He grew to admire Martin Luther King Jr. and supported creating Martin Luther King Jr. Day. In 2004, Buckley said, "I once believed we could evolve our way up from Jim Crow. I was wrong. Federal intervention was necessary."

Fighting Anti-Semitism

During the 1950s, Buckley worked to remove anti-Semitism (hatred of Jewish people) from the conservative movement. He did not allow anti-Semites to work for National Review. He believed that conservatism should include all Americans, no matter their background.

Foreign Policy Views

Buckley was strongly against communism. He supported overthrowing leftist governments, even if it meant using non-democratic forces. He admired Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco and praised him in his magazine. He also supported the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet in Chile.

Regarding the War in Iraq, Buckley later said that the American goal in Iraq had "failed." He believed that conservatism meant accepting reality, and the war had been unrealistic.

Spy Novelist

In 1975, Buckley was inspired to write a spy novel after reading The Day of the Jackal. He wanted to write a spy story that was clear about good and evil, unlike some other spy novels.

He wrote his first spy novel, Saving the Queen, in 1976. It featured a CIA agent named Blackford Oakes. This character was partly based on Buckley's own experiences in the CIA. Over the next 30 years, he wrote ten more novels about Oakes. His second book in the series, Stained Glass, won a National Book Award in 1980.

Buckley was very concerned about the idea that the CIA and the KGB (the Soviet spy agency) were morally the same. He wrote that comparing them was like saying a person who pushes an old lady into a bus is the same as a person who pushes an old lady out of the way of a bus.

Buckley started writing on computers in 1982. He was very loyal to a word processing program called WordStar, even as it became old-fashioned. He used it to write his last novel.

Later Career and Views

In 1988, Buckley helped defeat a liberal Republican Senator named Lowell Weicker in Connecticut. Buckley formed a group to campaign against Weicker and supported his Democratic opponent, Joseph Lieberman.

In 1991, Buckley received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George H. W. Bush. This is one of the highest civilian awards in the U.S. In 1990, when he turned 65, he retired from the daily management of National Review. He continued to write his newspaper column and articles for the magazine. He also gave lectures and interviews.

Thoughts on Modern Conservatism

Buckley criticized some parts of the modern conservative movement. About George W. Bush's presidency, he said that if a European leader had faced what the U.S. had, they would be expected to resign.

Some people believed Buckley saw the Iraq War as a "disaster." However, the editors of National Review noted that Buckley initially opposed the war but later thought the "surge" of troops deserved more time to work.

In a column in 2007, after his wife's death, Buckley seemed to suggest banning tobacco use in America. He linked his wife's death, in part, to her smoking.

Death and Lasting Impact

In his later years, Buckley suffered from emphysema and diabetes. In a December 2007 column, he said his emphysema was caused by his lifelong habit of smoking tobacco.

On February 27, 2008, he died from a heart attack at his home in Stamford, Connecticut. He was 82 years old. His son, Christopher Buckley, said his father "died with his boots on," meaning he died while still active. Buckley was buried next to his wife, Patricia, in Sharon, Connecticut.

Many important members of the Republican political world honored Buckley. President George W. Bush said, "He influenced a lot of people, including me." Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich said Buckley was the "indispensable intellectual advocate" for modern conservatism. Nancy Reagan, Ronald Reagan's widow, said, "Ronnie valued Bill's counsel throughout his political life."

Various organizations have awards named after Buckley to honor his contributions.

Language and Speaking Style

Buckley was famous for his excellent command of language. He did not learn English formally until he was seven years old, having first learned Spanish and French. He spoke English with a unique accent, a mix of old-fashioned upper-class American and British English, with a hint of a Southern accent.

He was known for being polite to his guests on Firing Line. However, during intense debates, like with Noam Chomsky and Gore Vidal, he could become less polite.

Some people say Buckley created a new way of speaking for conservatives. This "gladiatorial style" was flashy and combative, full of short, memorable phrases. It often led to exciting debates.

Nathan J. Robinson wrote that Buckley created a model for conservative thinkers. This model involved being confident, a good debater, witty, and referencing classic works.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: William F. Buckley, Jr. para niños

In Spanish: William F. Buckley, Jr. para niños