16th Street Baptist Church bombing facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 16th Street Baptist Church bombing |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights movement and the Birmingham campaign | |

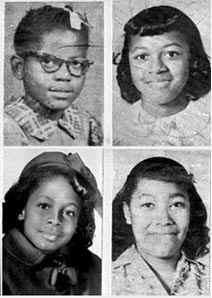

The four girls killed in the bombing (clockwise from top left) Addie Mae Collins (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11)

|

|

| Location | Birmingham, Alabama |

| Coordinates | 33°31′0″N 86°48′54″W / 33.51667°N 86.81500°W |

| Date | September 15, 1963; 62 years ago 10:22 a.m. (UTC-5) |

| Target | 16th Street Baptist Church |

|

Attack type

|

Bombing Domestic terrorism Right-wing terrorism |

| Deaths | 4 |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

14–22 |

| Victims | Addie Mae Collins Cynthia Wesley Carole Robertson Carol Denise McNair |

| Perpetrators | Thomas Blanton (convicted) Robert Chambliss (convicted) Bobby Cherry (convicted) Herman Cash (alleged) |

| Motive | Racism and support for racial segregation |

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was a terrible attack on the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. It happened on Sunday, September 15, 1963. Four members of a group called the Ku Klux Klan placed 19 sticks of dynamite with a timing device under the church steps.

This explosion killed four young girls and hurt between 14 and 22 other people. Martin Luther King Jr. called it "one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever done against people."

Even though the FBI knew by 1965 that four Klansmen were likely responsible, no one was charged until 1977. Later, in the early 2000s, two of the men, Thomas Blanton Jr. and Bobby Cherry, were finally found guilty and sent to prison for life. The bombing was a major event in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. It also helped gain support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, a law that fought against discrimination.

Contents

Birmingham's Segregated Past

In the years before the 1963 bombing, Birmingham was known as a very tense and violent city. It had strict rules about racial segregation, meaning black and white people were kept separate. Any attempts to mix races were met with strong, often violent, resistance. Martin Luther King Jr. even called Birmingham "probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States."

The city's Commissioner of Public Safety, Theophilus Eugene "Bull" Connor, used harsh methods to keep segregation in place. Black and white residents had separate public places, like water fountains and movie theaters. There were no black police officers or firefighters. Most black residents could only find low-paying jobs, like cooks or cleaners.

Black people also faced challenges to their freedom. It was very hard for them to register to vote. Bombings at black homes and churches were common. In the eight years before 1963, there were at least 21 explosions at black properties. None of these had caused deaths, but they earned the city the sad nickname "Bombingham."

The Birmingham Campaign for Rights

Civil Rights activists in Birmingham worked hard to fight against the city's deep-rooted racism. They used different methods, like protesting against unfair economic and social rules. They demanded that public places like lunch counters and parks be open to everyone. They also wanted an end to job discrimination. Their goal was to end segregation across Birmingham and the entire South. The work done in Birmingham was very important for the Civil Rights Movement. It showed other cities how to stand up against segregation and racism.

The 16th Street Baptist Church was a central meeting place for civil rights activities in 1963. When groups like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality started a campaign to help African Americans register to vote, tensions in the city grew. Important civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and Fred Shuttlesworth, used the church to plan and teach people how to march peacefully.

Children's Crusade

On May 2, 1963, more than 1,000 students, some as young as eight, left school to gather at the 16th Street Baptist Church. They were told to march downtown and talk to the mayor about segregation. They wanted to integrate buildings and businesses that were currently separated by race. This march faced strong resistance, and 600 people were arrested on the first day. However, the Birmingham campaign, including the Children's Crusade, continued until May 5. The goal was to fill the jails with protesters.

These protests led to an agreement on May 8 between city business leaders and the SCLC. They agreed to integrate public places, including schools, within 90 days. The first three schools in Birmingham were integrated on September 4.

However, some white people in Birmingham strongly opposed these changes. In the weeks after the schools were integrated, three more bombs exploded in Birmingham. Other violent acts followed the agreement. Some strong supporters of the Ku Klux Klan were very angry about the lack of resistance to integration. Because the 16th Street Baptist Church was a well-known meeting spot for civil rights activists, it became an obvious target.

The Church Bombing

In the early morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, four members of the United Klans of America—Thomas Edwin Blanton Jr., Robert Edward Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, and (it is believed) Herman Frank Cash—planted at least 15 sticks of dynamite. They placed it with a time delay under the church steps, near the basement.

Around 10:22 a.m., an unknown man called the 16th Street Baptist Church. A 14-year-old girl named Carolyn Maull, who was helping with Sunday School, answered. The caller simply said, "Three minutes," and then hung up. Less than a minute later, the bomb exploded. Five children were in the basement restroom, near the stairs, changing into choir robes. They were getting ready for a sermon called "A Rock That Will Not Roll."

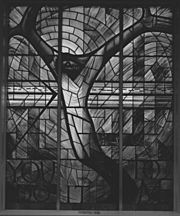

The explosion tore a large hole in the church's back wall. It also created a deep hole in the ladies' basement lounge and destroyed the back steps. Several cars parked nearby were ruined, and windows in buildings more than two blocks away were damaged. Almost all of the church's beautiful stained-glass windows were shattered. Only one window, showing Christ leading children, was mostly unharmed.

Hundreds of people, some hurt, rushed to the church to search for survivors. Police set up barriers, and some angry men argued with the police. About 2,000 black people gathered at the scene in the hours after the explosion. The church's pastor, the Reverend John Cross Jr., tried to calm the crowd by reading the 23rd Psalm loudly through a bullhorn.

Four young girls were killed in the attack:

- Addie Mae Collins (age 14)

- Carol Denise McNair (age 11)

- Carole Rosamond Robertson (age 14)

- Cynthia Dionne Wesley (age 14)

Between 14 and 22 other people were injured in the explosion.

Reactions to the Bombing

Rising Tensions

Violence quickly grew in Birmingham after the bombing. There were reports of groups of black and white young people throwing bricks and yelling insults at each other. Police asked parents to keep their children indoors. The Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, sent 300 more state police to help stop the unrest. The Birmingham City Council held an emergency meeting to discuss safety measures, but they decided against a curfew. Within 24 hours of the bombing, at least five businesses were firebombed, and many cars, mostly driven by white people, were hit with stones by angry young people.

The Mayor of Birmingham, Albert Boutwell, called the bombing "just sickening." In response, the Attorney General sent 25 FBI agents, including experts in explosives, to Birmingham to investigate thoroughly.

News of the church bombing and the deaths of the four young girls spread across the country and the world. Many people felt they had not taken the civil rights struggle seriously enough. The day after the bombing, a young white lawyer named Charles Morgan Jr. spoke to a group of businessmen. He criticized white people in Birmingham for accepting the unfair treatment of black people. In his speech, Morgan said, "Who did it [the bombing]? We all did it!" He meant that everyone who allowed hate to spread was partly responsible. A newspaper editorial from the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote, "For the rest of the nation, the Birmingham church bombing should serve to goad the conscience. The deaths ... in a sense, are on the hands of each of us."

Two more black young people were killed in Birmingham within seven hours of the Sunday morning bombing.

Some civil rights activists blamed George Wallace, the Governor of Alabama, for creating a hateful atmosphere. He was a strong supporter of segregation. One week before the bombing, Wallace told The New York Times that he thought Alabama needed "a few first-class funerals" to stop racial integration.

The city of Birmingham first offered a $52,000 reward for the bombers' arrest. Governor Wallace offered an additional $5,000 from the state of Alabama.

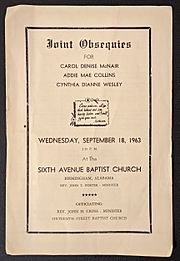

Funerals for the Girls

Carole Rosamond Robertson was buried in a private family funeral on September 17, 1963. Her service was held at St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church, with 1,600 people attending. The Reverend C. E. Thomas told the crowd, "The greatest tribute you can pay to Carole is to be calm, be lovely, be kind, be innocent." Carole Robertson was buried in a blue casket.

On September 18, the funeral for the other three girls was held at the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church. No city officials attended, but about 800 religious leaders of all races were there. Martin Luther King Jr. was also present. In his speech, King spoke to about 3,300 mourners, including many white people. He said:

This tragic day may cause the white side to come to terms with its conscience. In spite of the darkness of this hour, we must not become bitter ... We must not lose faith in our white brothers. Life is hard. At times as hard as crucible steel, but, today, you do not walk alone.

As the girls' coffins were taken to their graves, King asked everyone to remain quiet and not sing, shout, or protest.

The Investigation and Justice

The FBI faced challenges in their investigation. By 1965, they had four main suspects: Thomas Blanton Jr., Herman Frank Cash, Robert Chambliss, and Bobby Frank Cherry, all Klan members. However, witnesses were afraid to speak, and there wasn't enough physical evidence. Also, information from FBI surveillance couldn't be used in court back then. So, no federal charges were filed in the 1960s.

In 1968, the FBI officially closed their investigation without charging anyone. The files were sealed by order of the FBI Director, J. Edgar Hoover.

Reopening the Case

The case remained unsolved until William Baxley became the Attorney General of Alabama in January 1971. Baxley had been a student when the bombing happened and wanted to do something about it. He reopened the case in 1971. He was able to earn the trust of important witnesses who had been afraid to talk before. Some witnesses said Chambliss was the one who placed the bomb. Baxley also found evidence that Chambliss had bought dynamite less than two weeks before the bombing.

Baxley asked to see the original FBI files. He found out that the FBI had gathered evidence against the suspects but had not shared it with local prosecutors. After some resistance, Baxley finally received some of the FBI's evidence in 1976.

Robert Chambliss Convicted

On November 14, 1977, Robert Chambliss, then 73, went on trial in Birmingham. He was charged with four counts of murder. However, the judge decided he would be tried for the murder of Carol Denise McNair, with the other three charges remaining but not tried at that time.

Chambliss said he was not guilty. He claimed he had bought dynamite but gave it to another Klansman. On November 18, 1977, Robert Chambliss was found guilty of Carol Denise McNair's murder. He was sentenced to life in prison. He tried to appeal his conviction, saying the delay in his trial was unfair, but his appeal was denied.

Robert Chambliss died in prison on October 29, 1985, at age 81. He always said he was innocent.

Later Convictions

In 1995, ten years after Chambliss died, the FBI reopened the investigation. This was part of a larger effort to re-examine unsolved civil rights cases. They unsealed 9,000 pieces of evidence from the 1960s, much of which had not been given to William Baxley in the 1970s. In May 2000, the FBI announced that the bombing was done by four members of a Klan group called the Cahaba Boys. These were Blanton, Cash, Chambliss, and Cherry. Herman Cash had also died by this time, but Thomas Blanton and Bobby Cherry were still alive. Both were arrested.

On May 16, 2000, a grand jury charged Thomas Edwin Blanton and Bobby Frank Cherry with four counts of first-degree murder. Both men turned themselves in to the police.

Blanton was sentenced to life in prison and died there on June 26, 2020. Bobby Frank Cherry was also found guilty of four counts of first-degree murder and sentenced to life. He died of cancer in prison on November 18, 2004, at age 74.

Impact and Legacy

| They forever changed the face of this state and the history of this state. Their deaths made all of us focus upon the ugliness of those who would punish people because of the color of their skin. |

| —State Senator Roger Bedford at the unveiling of a state historic marker to the victims. September 15, 1990 |

The Birmingham campaign, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August, the September church bombing, and the November assassination of John F. Kennedy (who supported civil rights) all made people around the world more aware of and sympathetic to the civil rights cause in the United States.

After President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, the new President, Lyndon Johnson, continued to push for the civil rights bill. On July 2, 1964, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. Major Civil Rights Movement leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., were there. This law made it illegal to discriminate based on race, color, religion, gender, or national origin. It aimed to ensure equal rights for African Americans.

- The 16th Street Baptist Church was closed for over eight months for repairs after the bombing. The church and the families who lost loved ones received about $23,000 in cash donations. Gifts totaling over $186,000 came from all over the world. The church reopened on June 7, 1964, and is still an active place of worship today.

- Sarah Jean Collins, who was seriously injured in the bombing, stayed in the hospital for more than two months. Doctors initially worried she might lose her sight. When asked about the bombers, she said people were praying for them and that they would face God.

- Charles Morgan Jr., the white lawyer who spoke out against the hate in Birmingham, received death threats. Within three months, he and his family had to leave Birmingham.

- James Bevel, a key figure in the Civil Rights Movement, was inspired by the bombing to create the Alabama Project for Voting Rights. He and his wife, Diane, moved to Alabama to work on this project. Their efforts helped lead to the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which stopped racial discrimination in voting.

- Inside the 16th Street Baptist Church, there is a special Welsh Window. It was made by a Welsh artist named John Petts. He started a campaign in Wales to raise money for a new stained-glass window after the bombing. Petts chose to create a stained-glass image of a black Christ with outstretched arms.

- John Petts died in 1991. He once said, "Naturally, as a father, I was horrified by the deaths of those children." The Welsh Window has the words, "Given by The People of Wales," written on it.

- On the 27th anniversary of the bombing, a historic marker was placed at Greenwood Cemetery, where three of the four victims are buried. The four girls were called martyrs who "died so freedom could live."

- On May 24, 2013, President Barack Obama gave a special award, the Congressional Gold Medal, to the four girls who died. This medal recognized that their deaths helped push forward the Civil Rights Movement and led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The medal is now displayed at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Remembering the Bombing: Media and Memorials

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing has been remembered in many ways, including music, films, TV shows, books, and sculptures.

Music

- The song "Birmingham Sunday" by Richard Fariña (and sung by Joan Baez) is about the bombing.

- Nina Simone's 1964 song "Mississippi Godd**" was partly inspired by the bombing. The line "Alabama's got me so upset" refers to this event.

- Jazz musician John Coltrane's 1964 song "Alabama" was written as a musical tribute to the victims.

- Composer Adolphus Hailstork's 1982 work American Guernica was also created in memory of the victims.

Film and Television

- The 1997 documentary 4 Little Girls by Spike Lee focuses on the bombing and was nominated for an Academy Award.

- The 2002 movie Sins of the Father is a drama about the bombing.

- The 2014 historical drama Selma, which is about the 1965 marches, also shows a scene of the bombing.

- A 1993 documentary called Angels of Change and a History Channel documentary called Remembering the Birmingham Church Bombing have also covered the event.

Books

- Christopher Paul Curtis's 1995 novel The Watsons Go to Birmingham – 1963 tells a fictional story around the bombing.

- The 2001 novel Bombingham by Anthony Grooms is set in Birmingham in 1963 and includes the bombing.

- The American Girl book No Ordinary Sound, featuring Melody Ellison, has the bombing as a main part of its story.

Sculptures and Symbols

- The Welsh Window inside the church, created by John Petts, shows a black Jesus with outstretched arms, symbolizing forgiveness.

- American sculptor John Henry Waddell created a memorial called That Which Might Have Been: Birmingham 1963. It shows four adult women, representing the four victims as they might have grown up.

- The names of the four girls are carved on the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. This memorial honors 41 people who died fighting for equal rights between 1954 and 1968.

- The Four Spirits sculpture was unveiled in Birmingham's Kelly Ingram Park in September 2013 for the bombing's 50th anniversary. This life-size bronze and steel sculpture shows the four girls getting ready for church just before the explosion. The youngest girl, Carol Denise McNair, is shown releasing doves. The sculpture's base has the sermon title, "A Love That Forgives."

See also

- African-American history

- African Americans in Alabama

- Racial segregation of churches in the United States

- Timeline of African-American history

- Timeline of the civil rights movement

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |