Birmingham campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Birmingham Campaign |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

| Date | April 3 – May 10, 1963 | ||

| Location | |||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

The Birmingham campaign, also known as the Birmingham movement, was a series of protests in early 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama. It was organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to fight against racial segregation.

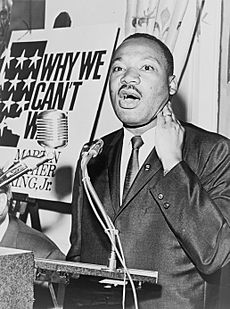

Leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., James Bevel, and Fred Shuttlesworth led peaceful protests. These actions led to major confrontations between young black students and white city officials. Eventually, the city government changed its unfair discrimination laws.

In the early 1960s, Birmingham was one of the most segregated cities in the United States. Black citizens faced unfair laws and limited opportunities. They also faced violence when they tried to speak up. Martin Luther King Jr. called it the most segregated city in the country.

Protests began with a boycott led by Fred Shuttlesworth. This boycott aimed to pressure businesses to hire people of all races and end segregation in public places. When business and government leaders resisted, the SCLC stepped in to help. They started "Project C," which involved sit-ins and marches to cause many arrests.

When there weren't enough adult volunteers, James Bevel suggested that students lead the protests. He trained high school, college, and even elementary school students in nonviolence. They were asked to walk peacefully from the 16th Street Baptist Church to City Hall. This led to over a thousand arrests. As jails filled, the city's Commissioner of Public Safety, Bull Connor, used high-pressure water hoses and police dogs on the children and bystanders. The students remained peaceful. This campaign brought a lot of attention to racial segregation in the South. It helped lead to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned racial discrimination across the U.S.

Contents

Why Birmingham Was Chosen

A Segregated City

In 1963, Birmingham, Alabama, was known as a very segregated city. Even though about 40% of the population was black, there were no black police officers, firefighters, or sales clerks in downtown stores. Black workers had very few job options, mostly manual labor or household service. They also earned much less than white workers. Public places were legally separated for black and white people, and these rules were strictly enforced. Only a small number of black citizens were allowed to vote.

The city also had a history of violence related to race. Many racially motivated bombings had occurred, earning the city the nickname "Bombingham". Black churches, where civil rights discussions took place, were often targets.

Local black leaders had been working for change for years. After the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was banned in Alabama in 1956, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth started the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR). He challenged segregation through lawsuits and protests. Shuttlesworth invited Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC to Birmingham, believing a victory there would inspire the whole nation.

Goals of the Campaign

King and the SCLC had learned lessons from an earlier campaign in Albany, Georgia, which didn't achieve all its goals. In Birmingham, they focused on specific targets in the downtown area. Their goals included ending segregation in downtown stores, ensuring fair hiring practices, reopening public parks, and creating a committee to oversee school desegregation. King explained that their direct actions aimed to create a situation so urgent that it would force negotiations.

The Role of Bull Connor

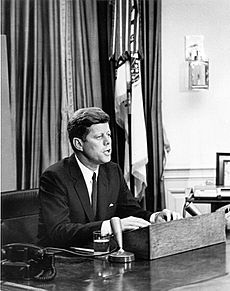

A key figure in the Birmingham campaign was Bull Connor, the city's Commissioner of Public Safety. He was a strong supporter of segregation. Connor believed the Civil Rights Movement was a communist plot. He had a lot of power in the city government. In 1961, he delayed sending police when Freedom Riders were attacked by mobs. His harsh actions against civil rights activists actually helped gain support for black Americans. President John F. Kennedy even said that Connor helped the Civil Rights Movement as much as Abraham Lincoln.

The city government was also weakened by political disagreements. Connor had lost the mayoral election in November 1962 to Albert Boutwell, a less extreme segregationist. However, Connor and his allies refused to leave office, claiming their terms weren't over. So, for a short time, Birmingham had two city governments, which caused confusion.

Protests Begin in Birmingham

Economic Pressure

Protests in Birmingham started in 1962 with student-led boycotts of downtown businesses. These boycotts caused a big drop in sales, getting the attention of business leaders. In response, the city government cut a food program that mainly helped low-income black families. This only made the black community more determined to resist.

The SCLC decided that putting economic pressure on businesses would be more effective than focusing on politicians. In the spring of 1963, before Easter, the boycott became even stronger. Pastors encouraged their church members to avoid shopping in downtown stores. Supporters watched the downtown area to make sure black shoppers were not going into segregated stores. If they saw someone, they would talk to them and encourage them to join the boycott.

Project C: Confrontation

Not everyone in the black community welcomed Martin Luther King Jr.'s presence in Birmingham. Some felt that the new city government should have more time to make changes.

However, protest organizers knew that the Birmingham Police Department would likely react with violence. They chose a confrontational approach to get the federal government's attention. Wyatt Tee Walker, an SCLC leader, planned "Project C," which stood for "confrontation." He aimed to provoke Bull Connor into reacting violently, which would then draw national media attention and sympathy. Organizers used code words for their plans because they suspected their phones were being listened to.

The plan involved nonviolent actions to highlight segregation in the "biggest and baddest city of the South." They planned sit-ins at libraries and lunch counters, and marches to government buildings.

Protest Methods

The campaign used various nonviolent methods. These included sit-ins at lunch counters, kneel-ins at white churches, and marches to encourage voter registration. Most businesses refused to serve the protesters. Some white onlookers even spat on participants during a sit-in. Hundreds of protesters were arrested, including jazz musician Al Hibbler.

The SCLC wanted to fill the jails with protesters to force the city government to negotiate. However, not enough people were arrested at first. Some in the black community questioned the plan. The editor of the city's black newspaper called the protests "wasteful." White religious leaders also criticized King, saying changes should happen through courts and negotiations, not street protests. Still, King promised daily protests until "peaceful equality had been assured."

City's Response

On April 10, 1963, Bull Connor got a court order to stop the protests. He also raised the bail money needed for arrested protesters. Fred Shuttlesworth called this order a "denial of our constitutional rights." The organizers decided to ignore the order, believing that obeying such orders had hurt their previous campaigns. Incoming mayor Albert Boutwell called King and the SCLC "strangers" who were only there to cause trouble. Connor promised to fill the jails with anyone breaking the law.

The movement ran low on money because of the high bail amounts. King was urged to raise funds, but he had promised to join the marchers in jail. After some hesitation, King and other leaders decided to defy the court order. On Good Friday, April 12, 1963, King was arrested along with about 50 other Birmingham residents. It was King's 13th arrest.

Martin Luther King Jr. in Jail

While in the Birmingham jail, Martin Luther King Jr. was initially denied a lawyer. His supporters quickly spread news of his arrest. King could have been released on bail, but campaign organizers decided not to pay it. They wanted to keep national attention on the situation in Birmingham.

After 24 hours, King was allowed to see his lawyers. When his wife, Coretta Scott King, didn't hear from him, she called President Kennedy directly. President Kennedy then called her, and King was soon allowed to call his wife.

While in jail, King wrote his famous essay, "Letter from Birmingham Jail." In it, he responded to eight white clergymen who had criticized him for causing trouble and not giving the new mayor a chance. This letter became a very important document of the Civil Rights Movement. King's arrest brought national attention, and businesses with stores in Birmingham began to lose money. They pressured the Kennedy administration to get involved. King was released from jail on April 20, 1963.

Protests Grow Stronger

Recruiting Students

Even with King's arrest, the campaign was struggling because not enough adults were willing to risk being arrested. To boost the movement, SCLC organizer James Bevel came up with a bold plan. He called it "D Day," and Newsweek magazine later called it the "Children's Crusade." This plan involved students from elementary schools, high schools, and Miles College joining the protests.

Bevel, who had experience with student protests, trained the young people in nonviolence. King was unsure about using children, but Bevel believed it was a good idea. He argued that if children were jailed, it wouldn't hurt families financially as much as an adult being arrested. He also saw that students were a more united group. He recruited school leaders and athletes, especially girls, who then inspired the boys to join.

Bevel and the SCLC held workshops to help students overcome their fears of police dogs and jail. They showed films of earlier sit-ins. Birmingham's black radio station, WENN, supported the plan by telling students to bring toothbrushes to jail. Flyers encouraged students to "Fight for freedom first then go to school."

The Children's Crusade

On May 2, 1963, hundreds of children, from first graders to high schoolers, walked out of school. They marched toward downtown Birmingham to meet the mayor and integrate segregated buildings. They left in small groups, singing hymns and "freedom songs" like "We Shall Overcome." More than 600 students were arrested, some as young as eight years old. The mood was described as being like a school picnic, even as they were arrested. Bull Connor and the police were surprised by the large number of children. They used police vans and school buses to take the children to jail. The day's arrests brought the total number of jailed protesters to 1,200.

The use of children in protests was controversial. Incoming mayor Albert Boutwell and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy both criticized the decision. However, King was deeply impressed by the children's success. He said he had "never seen anything like it." Wyatt Tee Walker, who was initially against using children, argued that "Negro children will get a better education in five days in jail than in five months in a segregated school." The Children's Crusade received front-page coverage in major newspapers.

Fire Hoses and Police Dogs

When Connor realized the jail was full, he changed police tactics on May 3. Another thousand students gathered at the church and marched toward Kelly Ingram Park, chanting for freedom. As they left the church, police warned them to stop or "you'll get wet." When the students continued, Connor ordered the city's fire hoses to be turned on them. The water pressure was strong enough to rip off shirts and push children over cars. When students fell, the water rolled them down the streets. Connor also allowed white onlookers to come closer, saying he wanted them to "see the dogs work."

Black parents and adults watching cheered the students, but when the hoses were used, some bystanders began throwing rocks and bottles at the police. To break up the crowd, Connor ordered police to use German Shepherd dogs. James Bevel warned the crowd to remain peaceful. That evening, King told worried parents, "Don't worry about your children who are in jail. The eyes of the world are on Birmingham. We're going on in spite of dogs and fire hoses."

Powerful Images

The images of children being attacked by fire hoses and police dogs had a huge impact. When the photos were released, the black community in Birmingham united behind King. People across the country and around the world were horrified. Senators in New York, Kentucky, and Oregon spoke out, comparing Birmingham to South Africa. Major newspapers called the police behavior "a national disgrace." President Kennedy sent Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall to Birmingham to help find a solution.

Standoff and Resolution

On May 5, some black onlookers in Kelly Ingram Park started throwing objects at the police, abandoning nonviolence. SCLC leaders urged them to be peaceful or leave. Connor ordered church doors blocked to stop more students from leaving.

By May 6, the jails were so full that Connor turned the state fairgrounds into a temporary jail. Black protesters also went to white churches to integrate services. Some churches accepted them, while others turned them away, leading to more arrests. Famous national figures like singer Joan Baez and comedian Dick Gregory came to show support.

Birmingham's fire department refused Connor's orders to use the hoses again. White business leaders met with protest organizers to try and find a solution. They said they couldn't control the politicians, but organizers argued that business leaders could pressure political leaders.

On May 7, the situation became a crisis. Jails were overflowing. Business leaders pleaded with organizers to stop the protests. The NAACP asked supporters to protest in 100 American cities. Twenty rabbis flew to Birmingham to support the cause.

Fire hoses were used again, injuring some protesters and Fred Shuttlesworth. Another 1,000 people were arrested, bringing the total to 2,500. News of the mass arrests of children reached Europe and the Soviet Union, drawing international criticism of the U.S. Alabama Governor George Wallace sent state troopers to help Connor. Attorney General Robert Kennedy considered sending federal troops.

Downtown Birmingham was paralyzed. Protesters planned to flood the downtown area. Smaller groups created diversions, and some set off false fire alarms. One group of children told a police officer, "We want to go to jail!" and ran across Kelly Ingram Park shouting it. Six hundred picketers reached downtown. Stores and streets were overwhelmed with over 3,000 protesters. Police admitted they couldn't handle the situation much longer.

Agreement Reached

On May 8, white business leaders agreed to most of the protesters' demands. On May 10, Fred Shuttlesworth and Martin Luther King Jr. announced an agreement. Birmingham would desegregate lunch counters, restrooms, and fitting rooms within 90 days. Stores would also hire black people as salespeople and clerks. Those in jail would be released. Labor unions raised a large sum of money to free the protesters. Bull Connor and the outgoing mayor condemned the agreement.

On the night of May 11, a bomb heavily damaged the Gaston Motel, where King had been staying. Another bomb damaged the home of A. D. King, Martin Luther King Jr.'s brother. Black citizens in the neighborhood reacted with anger, leading to unrest. By May 13, federal troops were sent to Birmingham to restore order. Martin Luther King Jr. returned to the city to emphasize nonviolence.

Outgoing mayor Art Hanes left office on May 21, 1963. Bull Connor, tearfully, said it was "the worst day of my life." In June 1963, the Jim Crow signs that enforced segregation in public places in Birmingham were finally taken down.

After the Campaign

Desegregation in Birmingham happened slowly after the protests. King and the SCLC were criticized by some for accepting an agreement that seemed too vague. However, by July, most of the city's segregation laws had been overturned. Some department store lunch counters became desegregated, and city parks and golf courses reopened to all citizens. A committee was formed to discuss further changes. However, hiring of black clerks, police officers, and firefighters was still slow.

Martin Luther King Jr.'s reputation grew greatly after the Birmingham protests. He was seen as a hero. The SCLC was asked to help with change in many other Southern cities. In the summer of 1963, King led the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where he gave his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. King was named Time's Man of the Year for 1963 and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

The Birmingham campaign, along with Governor George Wallace's refusal to allow black students into the University of Alabama, convinced President Kennedy that major changes were needed. He said that the events in Birmingham showed that no city or state could ignore the calls for equality. Kennedy's administration then created the Civil Rights Act of 1964 bill. After much debate in Congress, it was passed into law in 1964 and signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. This act banned racial discrimination in jobs and public places across the entire nation.

Birmingham's public schools were integrated in September 1963. Governor Wallace tried to stop black students from entering, but President Kennedy ordered troops to ensure the students could attend. However, violence continued in the city. Someone threw a tear gas canister into a department store that had desegregated, injuring many.

Four months after the Birmingham agreement, someone bombed the home of NAACP attorney Arthur Shores, injuring his wife. On September 15, 1963, members of the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church on a Sunday morning, killing four young girls.

The Birmingham campaign inspired the Civil Rights Movement in other parts of the South. Two days after the Birmingham settlement, Medgar Evers of the NAACP in Jackson, Mississippi, demanded a similar committee there. On June 12, 1963, Evers was killed by a KKK member. In 1965, Shuttlesworth, Bevel, and King led the Selma to Montgomery marches to help black citizens register to vote.

Impact of the Campaign

Historian Glenn Eskew wrote that the campaign "led to an awakening to the evils of segregation." The unrest that followed the Gaston Motel bombing showed what could happen in other cities later in the 1960s. One study of the Watts riots said that the "rules of the game" in race relations were forever changed in Birmingham.

Wyatt Tee Walker called the Birmingham campaign "legend" and the most important part of the Civil Rights Movement. He said it showed the SCLC had become a major force. Jonathan Bass noted that King won a "tremendous public relations victory" in Birmingham. However, he also stressed that it was the people of Birmingham, both black and white, who truly transformed the city.

See also

In Spanish: Campaña de Birmingham para niños

In Spanish: Campaña de Birmingham para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |