Jean-Paul Sartre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-Paul Sartre

|

|

|---|---|

Sartre in 1965

|

|

| Born |

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre

21 June 1905 |

| Died | 15 April 1980 (aged 74) Paris, France

|

| Education | École normale supérieure (BA, MA) |

| Partner(s) | Simone de Beauvoir (1929–1980) |

| Awards | Nobel Prize for Literature (1964, declined) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy, existentialism, phenomenology, existential phenomenology, hermeneutics, Western Marxism, anarchism |

|

Main interests

|

Metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, consciousness, self-consciousness, literature, political philosophy, ontology |

|

Notable ideas

|

Bad faith, "existence precedes essence", nothingness, "Hell is other people", situation, transcendence of the ego ("every positional consciousness of an object is a non-positional consciousness of itself"), the imaginary, being for itself, neocolonialism |

| Signature | |

|

|

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (born June 21, 1905, died April 15, 1980) was a famous French writer and thinker. He wrote plays, novels, and movie scripts. Many people see him as a very important figure in French philosophy from the 1900s. He also influenced Marxism, a way of thinking about society and economics. Sartre is best known for his ideas about existentialism, a philosophy about human freedom and responsibility. His work has made a big impact on how people study society, culture, and books.

In 1964, he was offered the Nobel Prize in Literature, a very important award for writers. However, Sartre chose to turn it down. He said he did not like official awards. He believed a writer should not become like an official organization.

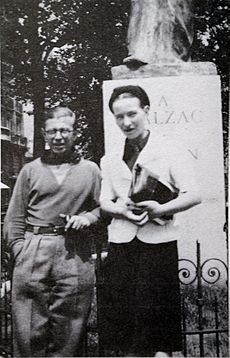

Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, another well-known philosopher and writer, were lifelong partners. They both challenged many common ideas and ways of life they grew up with. A big idea in Sartre's early work was the choice between living in "bad faith" (not being true to yourself) and living an "authentic" life (being true to yourself). His major book on this is Being and Nothingness (1943). A good way to start understanding his ideas is his lecture Existentialism Is a Humanism (1946).

Contents

Early Life and Education

Jean-Paul Sartre was born in Paris on June 21, 1905. His father, Jean-Baptiste Sartre, was a navy officer who died when Sartre was very young. His mother, Anne-Marie, moved back to her parents' home. Her father, Charles Schweitzer, helped raise Sartre. Charles was a German teacher who taught young Sartre math and introduced him to classic books. When Sartre was twelve, his mother remarried, and the family moved to La Rochelle. He was sometimes teased there, partly because of a problem with his right eye.

In the 1920s, as a teenager, Sartre became interested in philosophy. He read an essay by Henri Bergson. He then studied at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS), a top university in Paris. Many famous French thinkers went there. At ENS, Sartre met Raymond Aron, who became a lifelong friend. He also learned a lot from attending seminars by Alexandre Kojève.

Sartre was known for being a prankster at school. In 1927, he and his friends played a big prank. This happened after Charles Lindbergh flew from New York to Paris. They told newspapers that Lindbergh would get an honorary degree from their school. Many people, including journalists, showed up. They found out it was a trick with someone who looked like Lindbergh. This prank caused the school's director to resign.

In 1929, at ENS, he met Simone de Beauvoir. She was studying at the Sorbonne. She later became a famous philosopher, writer, and feminist. They became very close and were lifelong partners, though they also had other relationships. Sartre taught at high schools in different French cities from 1931 to 1945.

World War II Experiences

In 1939, when World War II started, Sartre joined the French Army. He worked as a meteorologist (someone who studies weather). In 1940, German soldiers captured him. He spent nine months as a prisoner of war. During this time, he wrote his first play, Barionà, fils du tonnerre. He also read Sein und Zeit (Being and Time) by Martin Heidegger, a German philosopher. This book greatly influenced Sartre's own ideas. Sartre was released in April 1941 because of poor health.

After returning to Paris in May 1941, he helped start an underground group. It was called Socialisme et Liberté (Socialism and Liberty). He formed it with Simone de Beauvoir and other writers. This group was part of the French Resistance against the German occupation. However, the group soon broke up. Sartre then decided to focus on writing. He wrote important books like Being and Nothingness. He also wrote plays like The Flies and No Exit. The German authorities did not censor these works.

Sartre wrote about life in Paris during the occupation. He said that the "correct" behavior of the German soldiers tricked many Parisians. People felt uncomfortable but often tried to be polite. Sartre felt this made them complicit. Food was scarce, and life was difficult. He described Paris as a "sham." It looked like its old self but was empty of its true spirit. The fear of informers also made it hard for people to speak freely. He noted that many people disappeared after being arrested by the Germans. The phrase "Hell is other people" from his play No Exit was partly inspired by living under occupation.

Some people later criticized Sartre for not being more active in the resistance. However, others, like the writer Albert Camus, considered him a writer who resisted through his work. After the war, Sartre wrote about minority groups, like French Jews and Black people. He spoke out against anti-Jewish prejudice.

Post-War: Politics and Ideas

After the war, Sartre became very involved in politics. He admired the French Resistance. He saw it as a time of true freedom and moral action. His 1948 play Dirty Hands explored the challenges of being a politically active thinker. He supported Marxism but did not join the Communist Party. For a while, he called for a "United States of Europe."

Sartre's views on the Soviet Union were complex. He initially saw it as a force for good. But he later criticized its actions, especially after the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956. He also spoke out against the repressive actions of Joseph Stalin.

Sartre was strongly against colonialism (when one country rules over another). He supported Algeria's fight for independence from France. Because of this, he became a target for a French paramilitary group. He survived two bomb attacks in the 1960s. He also opposed the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. With philosopher Bertrand Russell and others, he organized a tribunal to expose U.S. war crimes.

His book Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960) tried to combine Marxism with his own philosophy. He argued that the working classes in Europe were not as revolutionary as Marx had thought. Influenced by Frantz Fanon, he began to believe that poor people in developing countries (the Third World) would lead future revolutions.

Sartre visited Cuba in the 1960s. He met Fidel Castro and Ernesto "Che" Guevara. He admired Guevara, calling him "the most complete human being of our age." However, he also criticized Castro's government for its treatment of homosexuals.

Towards the end of his life, Sartre described himself as a kind of anarchist. This means he believed in a society without government.

Later Years and Death

In 1964, Sartre wrote The Words (Les Mots). This book was about the first ten years of his life. In it, he said that literature was, for him, a substitute for real action in the world. That same year, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, but he declined it. He was the first person to voluntarily refuse the prize. He said he did not want to be "transformed" by such an award. He also did not want to take sides in the cultural struggle between Eastern and Western countries.

Even though he became very famous, Sartre lived a simple life. He remained committed to political causes. This included the May 1968 student strikes in Paris. He was even arrested for civil disobedience (peacefully breaking a law to protest). The French President at the time, Charles de Gaulle, pardoned him. He said, "you don't arrest Voltaire" (another famous French writer and thinker).

Sartre's health got worse, partly due to his intense work schedule. He became almost blind in 1973. He died on April 15, 1980, in Paris from a problem with his lungs. About 50,000 people came to his funeral to honor him. He is buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris, alongside Simone de Beauvoir.

Sartre's Main Ideas

Sartre's most important idea is that humans are "condemned to be free." This means that we do not choose to be free, but we are. We are not born with a set purpose or nature, like a tool designed for a specific job.

He used the example of a paper cutter. Someone who makes a paper cutter has a plan for it. Its purpose (or "essence") exists before the paper cutter itself is made. But Sartre believed that for humans, it is the other way around. Since there is no God or creator who designed us, we simply exist first. Then, through our choices and actions, we create our own "essence" or purpose. This is what he meant by "existence precedes essence".

Because we create who we are, we are completely responsible for our actions. We cannot blame our nature or our past for what we do. We are "left alone, without excuse."

Sartre also talked about authenticity and "bad faith". To live authentically means to accept our freedom and responsibility. It means to make choices that are true to ourselves. To live in "bad faith" is to pretend we are not free. Or it is to blame others or circumstances for our choices. It is like lying to ourselves about our own freedom. He believed that facing the anxiety of our freedom and responsibility is part of living an authentic life.

Sartre as a Public Voice

Sartre was not just a thinker who wrote books. He was also a public intellectual. This means he used his ideas and his fame to speak out about important social and political issues. Before World War II, he was mostly focused on his writing and teaching. But the war showed him how important political events were. It showed him how they affected everyone.

After the war, he started a journal called Les Temps modernes (Modern Times). He encouraged writers to be politically engaged. He wanted them to use their work to make a difference. Sartre believed that culture was not fixed. He thought it was always being invented and reinvented. He spoke out against injustice and inequality wherever he saw it.

He generally supported left-wing ideas and the French Communist Party for a time. But he later criticized the party for being too controlling. In the late 1960s, he supported Maoist groups. These groups followed the Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong. They challenged established communist parties. However, he always said that he remained an anarchist at heart. This means he believed in freedom from oppressive systems.

Sartre's strong opinions sometimes put him in danger. For example, his support for Algeria's independence led to bomb attacks on his apartment. He believed it was important for thinkers to take a stand on issues like colonialism and human rights.

Sartre's Literary Works

Sartre was a successful writer in many forms. His plays often used symbols to explore his philosophical ideas. His most famous play, Huis-clos (No Exit), includes the well-known line "L'enfer, c'est les autres." This is usually translated as "Hell is other people." This line suggests that our relationships with others can be a source of suffering. This happens if we let their judgments define us.

His novel Nausea (La Nausée) is another important work. It explores the feeling of meaninglessness and the search for purpose. He also wrote a series of novels called The Roads to Freedom (Les Chemins de la Liberté). These show how World War II affected people's lives and ideas. These novels offer a more practical look at existentialism.

Sartre also wrote literary criticism and biographies. The Roman Catholic Church put his works on its list of prohibited books in 1948. This was because his ideas challenged religious beliefs.

See also

In Spanish: Jean-Paul Sartre para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Paul Sartre para niños

- Sartre's Roads to Freedom Trilogy

- Situation (Sartre)

- Place Jean-Paul-Sartre-et-Simone-de-Beauvoir

- 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |