Albert Camus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Albert Camus

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait from New York World-Telegram and Sun Photograph Collection, 1957.

|

|

| Born | 7 November 1913 Mondovi, French Algeria

|

| Died | 4 January 1960 (aged 46) |

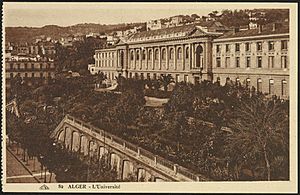

| Alma mater | University of Algiers |

|

Notable work

|

The Stranger / The Outsider The Myth of Sisyphus The Rebel The Plague |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

|

Main interests

|

Ethics, human nature, justice, politics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Absurdism |

|

Influences

|

|

| Signature | |

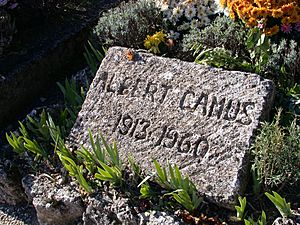

Albert Camus (born 7 November 1913 – died 4 January 1960) was a famous French writer, thinker, and journalist. He won the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature when he was 44 years old. This made him one of the youngest people ever to win it. Some of his most well-known books are The Stranger, The Plague, and The Myth of Sisyphus.

Camus was born in French Algeria, which was a French territory at the time. His family was not rich. He later studied philosophy at the University of Algiers. When World War II started, he was in Paris. He joined the French Resistance, a secret group fighting against the German occupation. He became the editor of an underground newspaper called Combat.

After the war, Camus became very famous. He traveled the world giving talks. He was interested in politics and was against totalitarianism, which is when a government has total control over people's lives. He believed in freedom and justice for everyone. Camus also supported the idea of European integration, where European countries work closely together. During the Algerian War, he tried to stay neutral. He wanted people from different backgrounds in Algeria to live together peacefully.

Camus's ideas helped create a philosophy called absurdism. This idea explores what happens when humans search for meaning in a world that doesn't seem to have any. Even though some people called him an existentialist, Camus himself did not like that label.

Contents

Life Story of Albert Camus

Early Years and School Days

Albert Camus was born on 7 November 1913 in Mondovi, French Algeria. His mother was French with Spanish family roots. His father died in World War I in 1914, so Camus never knew him. He grew up in a poor area of Algiers with his mother and other relatives.

Camus was a "Pied-Noir", which was a term for French people born in Algeria. Even though he was French, he grew up seeing how Arabs and Berbers were treated unfairly. As a child, he loved playing football and swimming.

In 1924, thanks to his teacher Louis Germain, Camus received a scholarship. This allowed him to attend a good secondary school in Algiers. When he was 17, he got tuberculosis, a lung disease. He moved in with his uncle, who helped him. Around this time, he became very interested in philosophy. His philosophy teacher, Jean Grenier, and thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche greatly influenced him.

Camus studied part-time to earn money. He worked as a tutor, a car parts clerk, and at a weather institute. In 1933, he started at the University of Algiers. He earned his philosophy degree in 1936. He studied ancient Greek philosophers and writers like Fyodor Dostoevsky and Franz Kafka.

From 1928 to 1930, Camus played as a goalkeeper for a junior football team. He loved the team spirit and courage in the game. He often said that the simple rules of football were clearer than the complex rules of society. His football dreams ended when his tuberculosis got worse.

Growing Up and Early Career

In 1934, Camus married Simone Hié. They later divorced.

Camus joined the French Communist Party in 1935. He wanted to fight against unfairness between Europeans and native Algerians. He left the party a year later. He then joined the Algerian Communist Party and helped organize a "Workers' Theatre" group. He also supported the Algerian People's Party, which wanted Algeria to be free.

Camus was later kicked out of the Communist Party. This made him believe even more in human dignity. He grew to distrust big organizations that cared more about being efficient than being fair. He continued his theater work, and some of his plays became ideas for his later novels.

In 1938, Camus started working for a newspaper called Alger républicain. He was strongly against fascism, a type of government that controls everything. He also spoke out against colonialism, which is when one country controls another. He saw how badly French authorities treated Arabs and Berbers.

The newspaper was banned in 1940. Camus moved to Paris and worked for Paris-Soir. In Paris, he almost finished his first set of works. These included the novel The Stranger, the essay The Myth of Sisyphus, and the play Caligula. These works explored the idea of the "absurd," or the meaninglessness of life.

World War II and the Resistance

Soon after Camus moved to Paris, World War II began. France was invaded by Germany. Camus tried to join the army but was not allowed because of his tuberculosis. He fled Paris and ended up in Lyon. On 3 December 1940, he married Francine Faure, a pianist and mathematician.

Camus and Francine moved back to Algeria. He taught in primary schools there. Because of his health, he moved to the French Alps. There, he started writing his second set of works, which were about "revolt." These included the novel The Plague and the play The Misunderstanding.

By 1943, Camus was becoming well-known. He returned to Paris and became friends with other famous thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre. He also became active in the secret French Resistance movement against the Germans. He worked as a journalist and editor for the banned newspaper Combat. He used a fake name and ID to avoid being caught. During this time, he wrote Letters to a German Friend, explaining why fighting back was important.

After World War II

After the war, Camus lived in Paris with Francine. Their twins, Catherine and Jean, were born in 1945. Camus was now a celebrated writer. He gave talks at universities in the United States and Latin America. He also visited Algeria again but was sad to see that unfair colonial policies continued.

During this time, he finished his second major work, the essay The Rebel. In this book, Camus criticized totalitarian communism. He supported libertarian socialism, which focuses on freedom and equality without a powerful government. This book caused him to disagree with many friends, including Jean-Paul Sartre. Their friendship ended because of their different views on communism.

Camus strongly supported the idea of European integration. He believed European countries should work together for peace and progress. He also spoke out against the Soviet Union's actions in Hungary and the strict government in Spain.

In 1957, Camus was surprised to learn he had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was 44, making him the second-youngest winner ever. With the prize money, he started writing his autobiography, Le Premier Homme (The First Man). He also adapted and directed a play based on Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel Demons.

Camus also helped publish the works of philosopher Simone Weil. He believed her writings were a way to fight against nihilism, the idea that life is meaningless. He called her "the only great spirit of our times."

His Death

Albert Camus died on 4 January 1960, at age 46, in a car accident near Sens, France. He was a passenger in a car driven by his publisher, Michel Gallimard. Camus died instantly. Gallimard died a few days later.

An unfinished book called Le premier Homme (The First Man) was found in the car. Camus had believed this book, about his childhood, would be his best work. He was buried in Lourmarin Cemetery in France. His friend Jean-Paul Sartre gave a speech, praising Camus's strong belief in humanity.

Literary Works

Camus's first published work was a play called Révolte dans les Asturies (Revolt in the Asturias) in 1936. It was about a miners' revolt in Spain. In 1937, he wrote his first book, L'Envers et l'Endroit (Betwixt and Between).

Camus organized his works into three main groups, or "cycles." Each cycle usually had a novel, an essay, and a play.

- The first cycle was about the absurd. It included The Stranger, The Myth of Sisyphus, and Caligula. These works explored the idea that life might not have a clear meaning.

- The second cycle was about revolt. It included The Plague, The Rebel, and The Just Assassins. These works looked at why people rebel against unfairness and what happens when they do.

- The third cycle was about love. It included Nemesis.

Camus started working on the second cycle during World War II. He used the Greek myth of Prometheus to show the difference between revolution and rebellion. He explored how rebellion can be a way to fight against injustice.

After winning the Nobel Prize, Camus published his thoughts on peace and the Algerian War in Algerian Chronicles. He then focused on theater and his third cycle of works.

Two of Camus's books were published after he died. A Happy Death (1970) was one. The other was the unfinished novel The First Man (1995). This book was about his childhood in Algeria. Its publication made people think more about Camus's views on colonialism.

| Years | Main Idea | Novel | Plays |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1937–42 | Absurdity | The Stranger | Caligula, The Misunderstanding |

| 1943–52 | Rebellion | The Plague | The State of Siege The Just |

| 1952–58 | Guilt, The Fall | The Fall | Adaptations of The Possessed (Dostoevsky); Faulkner's Requiem for a Nun |

| 1958– | The Kingdom | The First Man |

Camus's Political Views

Camus believed that good morals should guide politics. He disagreed with the idea that history alone defines what is right or wrong.

He was very critical of Marxism-Leninism, especially the Soviet Union. He thought the Soviet system was totalitarian, meaning it controlled people completely. Camus believed the Soviet Union was not truly socialist. He often argued with others on the political left, including his friend Jean-Paul Sartre, about this.

During World War II, Camus was active in the French Resistance against the Nazis. He wrote for and edited the Resistance newspaper Combat. After France was freed, he changed his mind about punishing those who worked with the Germans. He became a strong opponent of the death penalty for the rest of his life.

Camus had anarchist ideas, which grew stronger in the 1950s. He believed the Soviet system was wrong. He was against any kind of unfairness, strong authority, or too much government control. However, he was against violent revolution. He thought that revolutions often ended up creating new oppressive systems. He believed that rebellion should be about fighting for individual dignity and freedom, not causing unnecessary suffering.

Some experts, like David Sherman, consider Camus an anarcho-syndicalist. This means he supported workers' unions and believed in a society without a strong central government. Camus wrote for anarchist newspapers and magazines.

During the Algerian War (1954–1962), Camus tried to stay neutral. He was against the violence from both sides. He recognized the unfairness of French colonial rule but also opposed the violence of the National Liberation Front (FLN). He wanted Algerians of all backgrounds to live together peacefully. He tried to arrange a truce to protect civilians, but both sides rejected it. He also secretly helped Algerians who were sentenced to death.

Some critics, like Edward Said, have said that Camus's writings sometimes ignored or misrepresented the Arab people of Algeria. They felt he didn't fully understand the impact of colonialism. However, Camus once said that the problems in Algeria "affected him as others feel pain in their lungs," showing how deeply he cared.

Camus was also strongly against nuclear weapons and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In the 1950s, he worked for human rights. He resigned from UNESCO when the UN accepted Spain, which was then led by the dictator Francisco Franco. Camus remained a pacifist and fought against the death penalty worldwide.

His Role in Algeria

Camus was born in Algeria to French parents. He knew about the unfair treatment of Arabs and Berbers by France. Even though he grew up poor, he had more rights than the Arab and Berber majority because he was a French citizen.

Camus believed in a "new Mediterranean Culture." He imagined a future where all the different groups in Algeria could live together. He was against the idea of "Latiny," which was a pro-fascist and anti-Jewish idea among some French people in Algeria. Camus supported giving Algerians full French citizenship. In 1939, he wrote articles about the terrible living conditions of people in the Kabylie region. He called for urgent changes in the economy, education, and politics.

In 1945, after Arab revolts against French mistreatment, Camus was one of the few journalists to visit Algeria. He wrote articles about the situation, asking France to make changes and listen to the Algerian people.

When the Algerian War started in 1954, Camus faced a difficult choice. He felt a connection to the "Pieds-Noirs" (French people born in Algeria), like his own family. He also defended the French government's actions against the revolt. He believed the Algerian uprising was part of a larger "anti-Western" movement. He wanted Algerians and French people to live together, perhaps with more self-rule for Algeria, but not full independence.

During the war, he tried to get both sides to agree to a truce to protect civilians. But both sides rejected his idea. He also worked secretly to help Algerians who were facing the death penalty. His position was criticized by some who felt he was not doing enough to support Algerian independence.

Camus's Philosophy

Existentialism and the Absurd

Camus is often linked to absurdism, a philosophy that explores the idea that life might not have a clear meaning. He is also sometimes called an existentialist, but he himself did not like this term.

Camus said his ideas came from ancient Greek philosophy and thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche. He felt that his book, The Myth of Sisyphus, was a criticism of some parts of existentialism. He believed that the importance of history, as seen by thinkers like Karl Marx and Jean-Paul Sartre, did not fit with his belief in human freedom.

However, Camus's philosophy often dealt with questions about existence. He believed that the "absurd"—the idea that life has no clear meaning, or that humans can't know that meaning—is something we should accept. His ideas about individual freedom and responsibility are similar to those of other existentialist writers.

Camus's main idea about the Absurd is that it comes from the "confrontation between human need and the unreasonable silence of the world." This means that humans want life to have meaning, but the universe doesn't seem to provide one. Even though this feeling of absurdity is always there, Camus did not believe in nihilism, which is the idea that life is completely meaningless and has no value. Instead, he suggested that we accept the absurd and live fully despite it.

Camus later regretted being called a "philosopher of the absurd." He became less interested in the topic after writing The Myth of Sisyphus.

The Idea of Revolt

Camus is famous for explaining why people should rebel against unfairness, oppression, or anything that disrespects human dignity. However, he also set limits on rebellion. His book The Rebel explains his thoughts in detail.

In this book, he builds on the idea of the absurd. He concludes with the phrase, "I revolt, therefore we exist." This means that when one person rebels against injustice, it shows a shared human experience. Camus also explained the difference between a revolution and a rebellion. He noted that revolutions can sometimes lead to new oppressive systems. So, he stressed that morals must guide any rebellion.

Camus asked a very important question: Can humans act in a good and meaningful way in a world that seems silent and meaningless? He believed the answer was yes. He thought that understanding the absurd helps us create our own moral values and sets limits on our actions. He divided modern rebellion into two types:

- Metaphysical rebellion: This is when people protest against their basic human condition and against the whole world.

- Historical rebellion: This is when people try to make the ideas of metaphysical rebellion real and change the world. In this type of rebellion, people must be careful not to cause unfair suffering.

His Lasting Impact

Camus's novels and philosophical essays are still very important today. After his death, interest in his ideas grew. He is remembered for his thoughtful humanism and his support for political tolerance, open discussion, and civil rights.

Even though Camus was linked to anti-Soviet communism and even anarcho-syndicalism, some modern politicians have tried to connect him to their own ideas. For example, former French President Nicolas Sarkozy suggested moving Camus's remains to the Panthéon, a famous French monument. This idea was criticized by Camus's family and many people on the left.

Tributes to Camus

- In Tipaza (Algeria), a stone monument was put up in 1961 in honor of Albert Camus. It faces the sea and has a quote from his work: "I understand here what is called glory: the right to love beyond measure."

- The French Post Office released a stamp with his picture on 26 June 1967.

Works by Albert Camus

Novels

- A Happy Death (written 1936–38, published 1971)

- The Stranger (1942)

- The Plague (1947)

- The Fall (1956)

- The First Man (unfinished, published 1994)

Short Stories

- Exile and the Kingdom (collection, 1957), which includes:

- "The Renegade or a Confused Spirit"

- "The Silent Men"

- "The Guest"

- "Jonas, or the Artist at Work"

- "The Growing Stone"

Non-Fiction Books

- Betwixt and Between (collection, 1937)

- Nuptials (1938)

- The Myth of Sisyphus (1942)

- The Rebel (1951)

- Algerian Chronicles (1958)

- Resistance, Rebellion, and Death (collection, 1961)

Plays

- Caligula (performed 1945, written 1938)

- The Misunderstanding (1944)

- The State of Siege (1948)

- The Just Assassins (1949)

- Requiem for a Nun (adapted from William Faulkner's novel) (1956)

- The Possessed (adapted from Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel Demons) (1959)

Essays

- The Crisis of Man (Lecture at Columbia University) (1946)

- Neither Victims nor Executioners (Series of essays in Combat) (1946)

- Summer (1954)

- Reflections on the Guillotine (Extended essay, 1957)

- Create Dangerously (Lecture at the University of Uppsala) (1957)

See Also

In Spanish: Albert Camus para niños

In Spanish: Albert Camus para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |