Panthéon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Panthéon |

|

|---|---|

The Panthéon

|

|

| Former names | Église Sainte-Geneviève |

| General information | |

| Type | Mausoleum |

| Architectural style | Neoclassicism |

| Location | Place du Panthéon Paris, France |

| Coordinates | 48°50′46″N 2°20′45″E / 48.84611°N 2.34583°E |

| Construction started | 1758 |

| Completed | 1790 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Jacques-Germain Soufflot Jean-Baptiste Rondelet |

|

Monument historique

|

|

| Designated: | 1920 |

| Reference #: | PA00088420 |

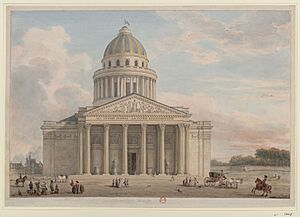

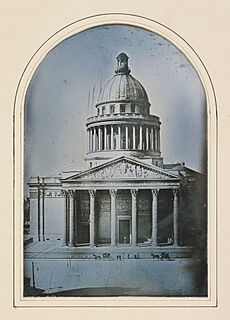

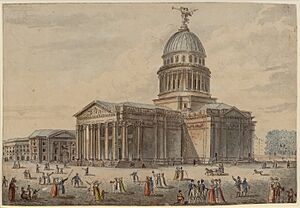

The Panthéon is a famous building in Paris, France. Its name comes from an old Greek word meaning "to all the gods." It stands in the Latin Quarter, on top of a hill called Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. The building was constructed between 1758 and 1790.

King Louis XV of France wanted it to be a church. It was meant to honor Saint Genevieve, who was the patron saint of Paris. Her important relics were supposed to be kept there. However, neither the king nor the architect, Jacques-Germain Soufflot, lived to see it finished.

When the building was finally done, the French Revolution had begun. In 1791, leaders decided to change the church into a mausoleum. This meant it would be a special burial place for important French citizens. It was inspired by the Pantheon in Rome. The Panthéon was used as a church again a few times in the 1800s. But in 1881, it became a mausoleum for good.

The building's purpose changed many times. This led to changes in its sculptures and the top of its dome. Some windows were even blocked to make the inside darker and more serious. This was different from the architect's original idea of a bright, light building. The Panthéon is an early example of Neoclassicism, a style that used ideas from ancient Greek and Roman buildings.

In 1851, a scientist named Léon Foucault did an experiment there. He hung a long pendulum from the ceiling to show that the Earth rotates. A copy of this pendulum is still there today. As of 2021, the remains of 81 people, including many famous French figures, have been placed in the Panthéon.

History of the Panthéon

Building on a Historic Site

The place where the Panthéon stands is very important in Paris's history. It was once Mount Lucotitius, where the Roman town of Lutetia had its main public square. It was also the first burial spot of Saint Genevieve. She was famous for leading the people of Paris against the Huns in 451.

In 508, Clovis I, the King of the Franks, built a church there. He and his wife were later buried in this church. It was first for Saints Peter and Paul, but then it was rededicated to Saint Genevieve. Her relics were kept there and used in parades to protect the city.

How the Panthéon Was Built

In 1744, King Louis XV promised to build a grand church. He made this promise after he recovered from an illness. He wanted to replace the old, worn-out church of Saint Genevieve. Ten years later, the work finally began.

In 1755, Jacques-Germain Soufflot was chosen to design the new church. Soufflot had studied old Roman buildings in Italy. The church of Saint Genevieve became his life's work, but he died before it was finished.

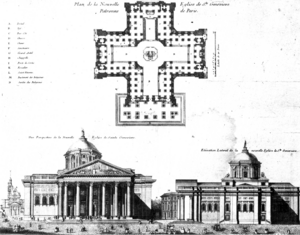

His first design was ready in 1755. It looked like a Greek cross, with four equal arms. It had a huge dome in the middle and a classic front with tall columns. The design changed five times over the years. They added a front hall, a choir, and two towers. The final design was approved in 1777.

Building started in 1758, but it was slow because of money problems. Soufflot died in 1780, and his student, Jean-Baptiste Rondelet, took over. The church was finally completed in 1790, just as the French Revolution was starting.

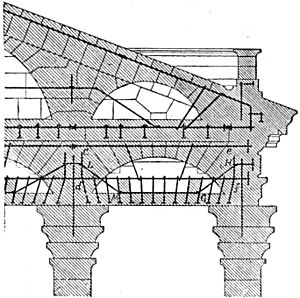

The building is 110 meters long, 84 meters wide, and 83 meters high. The crypt, or underground area, is the same size. The ceiling is held up by columns and arches. The huge dome rests on four massive pillars. Some people worried the pillars couldn't hold such a big dome. Soufflot used iron rods to make the stone structure stronger. This was an early form of reinforced building. These rods needed repair in the 21st century, and a big restoration happened from 2010 to 2020.

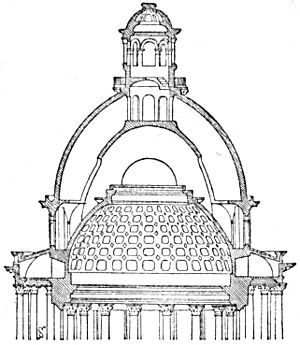

The dome is actually three domes, one inside the other. The lowest dome has a patterned ceiling. Through its center, you can see the second dome. This second dome is decorated with a painting called The Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve. The outer dome, which you see from outside, is made of stone and covered with lead. Hidden supports inside the walls help hold up the dome.

The Revolution: From Church to "Temple of the Nation"

The Church of Saint Genevieve was almost finished when the French Revolution began in 1789. In 1791, leaders decided to turn it into a "temple of the nation." They wanted it to be a place to honor great French citizens. The idea was to put statues of important people there and bury their remains underground.

This idea was approved after the death of Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, a key revolutionary figure. On April 4, 1791, it was declared that the church would become a "temple of the nation." A new message was put above the entrance: "A grateful nation honors its great men." Mirabeau's funeral was held there the same day.

The remains of Voltaire, a famous writer, were placed in the Panthéon in a grand ceremony. Later, the remains of other revolutionaries, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, were also moved there. However, some of the first people honored, like Mirabeau, were later removed as political power shifted. In 1795, a new rule said that no one could be placed in the Panthéon unless they had been dead for at least ten years.

After it became a mausoleum, the building was changed to be darker and more serious. Windows were blocked up, and much of the outside decoration was removed. Religious sculptures and art were replaced with patriotic themes.

Changes Over Time: Temple to Church and Back Again (1806–1871)

When Napoleon Bonaparte became leader in 1801, he made an agreement with the Pope. This agreement returned many church properties, including the Panthéon, to the Catholic Church. Important events, like Napoleon's victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, were celebrated there. However, the crypt, or underground burial area, remained a resting place for famous French people. A new entrance was even made directly to the crypt.

The artist Antoine-Jean Gros was asked to paint the inside of the dome. His painting showed Saint Genevieve going to heaven, surrounded by great French leaders. These leaders included Clovis I, Charlemagne, and Napoleon. During Napoleon's rule, the remains of 41 important Frenchmen were placed in the crypt. Most were military officers or government officials.

After Napoleon's fall, King Louis XVIII of France returned the entire Panthéon to the Catholic Church in 1816. The church was officially consecrated. The sculpture on the front, which showed "The Fatherland crowning heroic virtues," was replaced with a religious one. Some of Saint Genevieve's relics, which had been destroyed, were found and returned. New paintings were added to the dome's supports, showing "Justice," "Death," "The Nation," and "Fame." The crypt was locked and closed to visitors.

In 1830, Louis Philippe I became king. He changed the church back to the Panthéon. However, the crypt stayed closed, and no new burials happened. The only change was to the main front. A new sculpture was added, showing "The Nation Distributing Crowns" to great men.

In 1848, Louis Philippe was overthrown, and the Second French Republic began. The new government called the Panthéon "The Temple of Humanity." They planned to add many new murals celebrating human progress. In 1851, Léon Foucault hung his famous pendulum there to show the Earth's rotation. But the Church complained, and it was removed later that year.

When Napoleon III became Emperor in 1852, the Panthéon was again returned to the church. It was called the "National Basilica." The relics of Saint Genevieve were brought back, and new sculptures were added. The crypt remained closed.

The Third Republic (1871–1939)

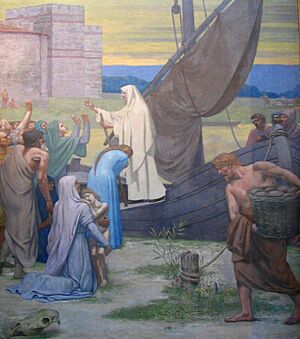

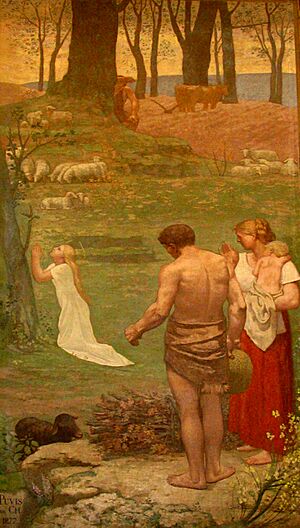

The Panthéon was damaged during the 1870 Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune in 1871. In the early years of the French Third Republic, it was a church, but its walls were mostly bare. Starting in 1874, new murals and sculptures were added. These artworks connected French history with the history of the church. Famous artists like Puvis de Chavannes and Alexandre Cabanel created these pieces.

In 1881, a new law turned the church back into a mausoleum. Victor Hugo, a famous writer, was the first person to be buried in the crypt after this change. Later, other literary figures like Émile Zola (1908) were interred. After World War I, leaders of the French socialist movement, such as Léon Gambetta (1920) and Jean Jaurès (1924), were also honored.

The Third Republic also decided that the building should have sculptures showing "the golden ages and great men of France." Important works from this time include a sculpture called The National Assembly, which remembers the French Revolution. There is also a statue of Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, the first person buried in the Panthéon. Two patriotic murals were added in the apse: Victory Leading the Armies of the Republic and Glory Entering the Temple.

From 1945 to Today

After World War II, during the French Fourth Republic, two scientists, Paul Langevin and Jean Perrin, were honored. Also, Victor Schœlcher, a leader of the movement to end slavery, and Félix Éboué, an early leader of Free France, were interred. In 1952, Louis Braille, who invented the Braille writing system for the blind, was also honored.

Under the French Fifth Republic, led by President Charles de Gaulle, the first person buried in the Panthéon was Jean Moulin. He was a leader of the French Resistance during WWII. More recently, important figures include Nobel Peace Prize winner René Cassin (1987), who helped write the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Jean Monnet (1988), who helped create the European Union's early forms, was also interred.

In 1995, the Nobel Prize-winning scientists Marie Curie and Pierre Curie were buried there. Marie Curie was the first woman to be honored in the Panthéon for her own achievements. Other notable people include writer and politician André Malraux (1996) and lawyer and politician Simone Veil (2018). In 2021, Josephine Baker, a famous entertainer and civil rights activist, became the first Black woman to be honored there.

Architecture and Art

The Grand Dome

The final design for the dome was approved in 1777 and finished in 1790. It was meant to be as impressive as the domes of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and St Paul's Cathedral in London. Unlike many French domes, this one is built entirely of stone, not wood. It actually has three domes, one inside the other. The painted ceiling you see from below is on the second dome. The dome is 83 meters (272 feet) high.

A cross sits on top of the dome today. Originally, a statue of Saint Genevieve was planned. A cross was put there temporarily in 1790. After it became a mausoleum in 1791, they planned to replace the cross with a statue of Fame, but this idea was dropped. Between 1830 and 1851, a flag was on top instead. The cross returned when the building became a church again. During the Paris Commune in 1871, a red flag was placed there. The cross returned later.

If you look up from under the dome, you can see a painting by Jean-Antoine Gros. It's called The Apotheosis of Saint Genevieve (1811–1834). The triangle in the middle represents the Trinity, surrounded by light. The only full figure you see is Saint Genevieve herself. Around the painting are groups representing French kings who protected the church. These include Clovis I, the first king to become Christian, and Charlemagne, who started the first universities. Another group shows Louis IX of France, or Saint Louis, with the Crown of Thorns. The last group shows Louis XVIII and his niece, looking up at the martyred Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Angels in the painting carry a document that re-established the church after the French Revolution.

The four arches that support the dome have paintings by François Gérard. These paintings, from 1821–37, show Glory, Death, The Nation, and Justice.

Front of the Panthéon

The front of the Panthéon, on the east side, looks like an ancient Greek temple. It has Corinthian columns and a triangular sculpture above them, called a pedimental sculpture. This sculpture was made by David d'Angers and finished in 1837. It replaced an earlier one with religious themes. The sculpture shows "The Nation distributing crowns handed to her by Liberty to great men, civil and military, while history inscribes their names."

On the left side of the sculpture are important scientists, philosophers, and statesmen. These include Rousseau, Voltaire, and Lafayette. On the right side is Napoleon Bonaparte, along with soldiers and students. Below the sculpture, there is an inscription that says: "To the great men, from a grateful nation." This message was added in 1791 when the Panthéon was created. It was removed and then put back in 1830.

Below the columns are five carved pictures called bas-reliefs. The two above the main doors show the building's two main purposes. The one on the left is "Public Education," and the one on the right is "Patriotic Devotion."

The front of the building originally had large windows. But these were replaced when the church became a mausoleum. This was done to make the inside darker and more serious.

Inside the Panthéon

The main part of the Panthéon, called the Western Nave, has many paintings. These paintings show the lives of Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris, and a longer series about the life of Saint Genevieve. These were painted by famous artists like Puvis de Chavannes and Alexandre Cabanel. The paintings in the Southern and Northern Naves continue this story of French Christian heroes. They include scenes from the lives of Charlemagne, Clovis I, Louis IX of France, and Joan of Arc. From 1906 to 1922, Auguste Rodin's famous sculpture The Thinker was displayed here.

The Foucault Pendulum

In 1851, a physicist named Léon Foucault showed how the Earth rotates. He did this by hanging a 67-meter (220-foot) pendulum from the central dome. The original ball from the pendulum was shown at the Panthéon in the 1990s during renovations. The original pendulum is now back at the Musée des Arts et Métiers, and a copy is displayed at the Panthéon. Since 1920, the Panthéon has been listed as a monument historique by the French government.

Burials in the Crypt

Being buried in the Panthéon's crypt is a very high honor. It is only allowed by a special law for "National Heroes." Similar honors exist for military leaders like Napoléon at another place called Les Invalides.

Some of the famous people buried in the Panthéon include Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Victor Hugo, Émile Zola, Jean Moulin, Louis Braille, Jean Jaurès, and Soufflot, who was the architect of the building. In 1907, Marcellin Berthelot, a scientist, was buried with his wife, Sophie Berthelot. He had said he wouldn't be buried without her. Marie Curie was buried in 1995. She was the first woman to be honored there for her own achievements.

Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz and Germaine Tillion, who were heroes of the French resistance during WWII, were buried in 2015. Simone Veil, a politician and Holocaust survivor, was interred in 2018. Her husband, Antoine Veil, was buried next to her so they wouldn't be separated.

A common story that Voltaire's remains were stolen in 1814 is not true. His coffin was opened in 1897, and his remains were still there.

On November 30, 2002, the coffin of Alexandre Dumas, the author of The Three Musketeers, was carried to the Panthéon. His coffin was covered in blue velvet with the Musketeers' motto: "One for all, all for one." His remains were moved from his original burial place. President Jacques Chirac said that this was correcting an old unfairness by honoring one of France's greatest writers.

In January 2007, President Jacques Chirac placed a plaque in the Panthéon. It honors more than 2,600 people known as Righteous Among the Nations. These are people recognized by the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel for saving Jews during the Holocaust. This tribute highlights that about three-quarters of France's Jewish population survived the war. This was often thanks to ordinary people who helped them, risking their own lives.

The plaque says:

|

Sous la chape de haine et de nuit tombée sur la France dans les années d'Occupation, des lumières, par milliers, refusèrent de s'éteindre. Nommés "Justes parmi les nations" ou restés anonymes, des femmes et des hommes, de toutes origines et de toutes conditions, ont sauvé des juifs des persécutions antisémites et des camps d'extermination. Bravant les risques encourus, ils ont incarné l'honneur de la France, ses valeurs de justice, de tolérance et d'humanité. |

Under the cloak of hatred and darkness that spread over France during the years of [Nazi] occupation, thousands of lights refused to be extinguished. Named as "Righteous among the Nations" or remaining anonymous, women and men, of all backgrounds and social classes, saved Jews from anti-Semitic persecution and the extermination camps. Braving the risks involved, they embodied the honour of France, and its values of justice, tolerance and humanity. |

People Honored at the Panthéon

| Year | Name | Lived | Profession | Burial | Picture | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1791 | Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau | 1749–1791 | Revolutionary leader | — | — | First person honored with burial in the Panthéon. His remains were later removed. |

| 1791 | Voltaire | 1694–1778 | Writer and philosopher | Entrée |  |

|

| 1792 | Nicolas-Joseph Beaurepaire | 1740–1792 | Military officer | — | — | His remains have since disappeared. |

| 1793 | Louis Michel le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau | 1760–1793 | Politician | — | — | His remains were removed from the Panthéon at his family's request. |

| 1793 | Auguste Marie Henri Picot de Dampierre | 1756–1793 | Military officer | — | — | His remains have since disappeared. |

| 1794 | Jean-Paul Marat | 1743–1793 | Politician | — | — | His remains were removed from the Panthéon. |

| 1794 | Jean-Jacques Rousseau | 1712–1778 | Writer and Philosopher | Entrée |  |

|

| 1806 | François Denis Tronchet | 1726–1806 | Politician and lawyer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1806 | Claude-Louis Petiet | 1749–1806 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1807 | Jean-Étienne-Marie Portalis | 1746–1807 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1807 | Louis-Pierre-Pantaléon Resnier | 1759–1807 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1807 | Louis-Joseph-Charles-Amable d'Albert, duc de Luynes | 1748—1807 | Politician | — | — | His remains were removed from the Panthéon in 1862 at his family's request. |

| 1807 | Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Bevière | 1723–1807 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | François Barthélemy, comte Beguinot | 1747–1808 | Military officer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Pierre Jean Georges Cabanis | 1757–1808 | Scientist and philosopher | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Gabriel-Louis, marquis de Caulaincourt | 1741–1808 | Military officer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Jean-Frédéric Perregaux | 1744–1808 | Banker | Crypt IV | ||

| 1808 | Antoine-César de Choiseul, duc de Praslin | 1756–1808 | Military officer and politician | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1808 | Jean-Pierre Firmin Malher | 1761–1808 | Military officer | Crypt V |  |

Urn with his heart. |

| 1809 | Jean Baptiste Papin, comte de Saint-Christau | 1756–1809 | Politician and lawyer | Crypt V |  |

|

| 1809 | Joseph-Marie Vien | 1716–1809 | Painter | Crypt III | ||

| 1809 | Pierre Garnier de Laboissière | 1755–1809 | Military officer | Crypt III | ||

| 1809 | Jean Pierre, comte Sers | 1746–1809 | Politician | Crypt III | Urn with his heart. | |

| 1809 | Jérôme-Louis-François-Joseph, comte de Durazzo | 1739–1809 | Politician | Crypt V |  |

Urn with his heart. |

| 1809 | Justin Bonaventure Morard de Galles | 1761–1809 | Military officer | Crypt III | Urn with his heart. | |

| 1809 | Emmanuel Crétet de Champmol | 1747–1809 | Politician | Crypt III | ||

| 1810 | Cardinal Giovanni Battista Caprara | 1733–1810 | Clergyman | Crypt III | His body was later removed from the Panthéon and returned to his family. | |

| 1810 | Louis Charles Vincent Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire | 1766–1809 | Military officer | Crypt III | ||

| 1810 | Jean-Baptiste Treilhard | 1742–1810 | Lawyer | Crypt III | ||

| 1810 | Jean Lannes de Montebello | 1769–1809 | Military officer | Crypt XXII |  |

|

| 1810 | Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu | 1738–1810 | Politician | Crypt III | ||

| 1811 | Louis Antoine de Bougainville | 1729–1811 | Navigator | Crypt III |  |

|

| 1811 | Cardinal Charles Erskine de Kellie | 1739–1811 | Clergyman | Crypt III | ||

| 1811 | Alexandre-Antoine Hureau de Sénarmont | 1769–1811 | Military officer | Crypt II | Urn with his heart. | |

| 1811 | Cardinal Ippolito Antonio, cardinal Vincenti Mareri | 1738–1811 | Clergyman | Crypt III |  |

|

| 1811 | Nicolas Marie Songis des Courbons | 1761–1811 | Military officer | Crypt III | ||

| 1811 | Michel Ordener, 1st Count Ordener | 1755–1811 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1812 | Jean Marie Pierre Dorsenne | 1773–1812 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1812 | Jan Willem de Winter | 1761–1812 | Military officer | Crypt IV | Heart buried in his birthplace, Netherlands. | |

| 1813 | Hyacinthe-Hugues-Timoléon de Cossé, Comte de Brissac | 1746–1813 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1813 | Jean-Ignace Jacqueminot, Comte de Ham | 1758–1813 | Lawyer | Crypt II | ||

| 1813 | Joseph-Louis Lagrange | 1736–1813 | Mathematician | Crypt II |  |

|

| 1813 | Jean Rousseau | 1738–1813 | Politician | Crypt II | ||

| 1813 | Justin de Viry | 1737–1813 | Politician | Crypt II | ||

| 1814 | Frédéric Henri Walther | 1761–1813 | Military officer | Crypt IV | ||

| 1814 | Jean-Nicolas Démeunier | 1751–1814 | Politician | Crypt II | ||

| 1814 | Jean-Louis-Ébénézer Reynier | 1771–1814 | Military officer | Crypt IV | ||

| 1814 | Claude Ambroise Régnier de Massa di Carrara | 1746–1814 | Politician and lawyer | Crypt II | ||

| 1815 | Antoine-Jean-Marie Thévenard | 1733–1815 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1815 | Claude-Juste-Alexandre Legrand | 1762–1815 | Military officer | Crypt II | ||

| 1829 | Jacques-Germain Soufflot | 1713–1780 | Architect of the Pantheon | Entrée |  |

|

| 1885 | Victor Hugo | 1802–1885 | Writer | Crypt XXIV |  |

|

| 1889 | Lazare Carnot | 1753–1823 | Politician and scientist | Crypt XXIII |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon for the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. |

| 1889 | Jean-Baptiste Baudin | 1811–1851 | Politician and doctor | Crypt XXIII | Transferred to the Panthéon for the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. | |

| 1889 | Théophile Corret de la Tour d'Auvergne | 1743–1800 | Military officer | Crypt XXIII | Transferred to the Panthéon for the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. | |

| 1889 | François Séverin Marceau | 1769–1796 | Military officer | Crypt XXIII |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon from Koblenz, Germany, for the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution. |

| 1894 | Marie François Sadi Carnot | 1837–1894 | President of France | Crypt XXIII | Buried in the Panthéon right after he was assassinated. | |

| 1907 | Marcellin Berthelot | 1827–1907 | Scientist | Crypt XXV |  |

Buried with his wife Sophie Berthelot because he didn't want to be buried without her. |

| 1907 | Sophie Berthelot | 1837–1907 | Wife of Marcellin Berthelot | Crypt XXV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon with her husband. The first woman to be buried in the Panthéon. |

| 1908 | Émile Zola | 1840–1902 | Writer | Crypt XXIV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon from Montmartre Cemetery. |

| 1920 | Léon Gambetta | 1838–1882 | Politician | Escalier d'accès |  |

Urn with his heart. |

| 1924 | Jean Jaurès | 1859–1914 | Politician | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon ten years after he was assassinated. |

| 1933 | Paul Painlevé | 1863–1933 | Mathematician and politician | Crypt XXV |  |

|

| 1948 | Paul Langevin | 1872–1946 | Scientist | Crypt XXV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Jean Perrin. |

| 1948 | Jean Perrin Nobel Laureate |

1870–1942 | Scientist | Crypt XXV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Paul Langevin. His remains were brought back from New York City, US. |

| 1949 | Victor Schœlcher | 1804–1893 | Abolitionist | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Félix Éboué. He wanted to be buried with his father, Marc, so his father was also interred. |

| 1949 | Marc Schœlcher | 1766–1832 | Father of Victor Schœlcher | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Victor Schœlcher, as Victor wanted to be buried with him. |

| 1949 | Félix Éboué | 1884–1944 | Politician | Crypt XXVI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon the same day as Victor Schœlcher. |

| 1952 | Louis Braille | 1809–1852 | Educator | Crypt XXV | Transferred to the Panthéon on the 100th anniversary of his death. | |

| 1964 | Jean Moulin | 1899–1943 | Resistance fighter | Crypt VI |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon from Père Lachaise Cemetery on December 19, 1964. |

| 1967 | Antoine de Saint-Exupéry | 1900–1944 | Writer | — |  |

Honored with an inscription in November 1967, as his body was never found after a plane fight. |

| 1987 | René Cassin Nobel Laureate |

1887–1976 | Human rights activist | Crypt VI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon on the 100th anniversary of his birth. |

| 1988 | Jean Monnet | 1888–1979 | Economist | Crypt VI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon on the 100th anniversary of his birth. |

| 1989 | Abbé Henri Grégoire | 1750–1831 | Clergyman | Crypt VII |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon for the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. |

| 1989 | Gaspard Monge | 1746–1818 | Mathematician | Crypt VII |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon for the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. |

| 1989 | Nicolas de Condorcet | 1743–1794 | Politician | Crypt VII |  |

Honored with a symbolic burial for the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. His coffin is empty as his remains were lost. |

| 1995 | Pierre Curie Nobel Laureate (1903) |

1859–1906 | Scientist | Crypt VIII | Transferred to the Panthéon in April 1995 with his wife and fellow physicist Marie Curie. | |

| 1995 | Marie Skłodowska Curie Nobel Laureate (1903 and 1911) |

1867–1934 | Scientist | Crypt VIII | Second woman to be buried in the Panthéon, but the first to be honored for her own achievements. | |

| 1996 | André Malraux | 1901–1976 | Writer and politician | Crypt VI |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon on November 23, 1996, for the 20th anniversary of his death. |

| 1998 | Toussaint Louverture | 1743–1803 | Military officer | — | Commemorative plaque installed on the same day as for Louis Delgrès. | |

| 1998 | Louis Delgrès | 1766–1802 | Politician | — | Commemorative plaque installed on the same day as for Toussaint Louverture. | |

| 2002 | Alexandre Dumas | 1802–1870 | Writer | Crypt XXIV |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon 132 years after his death. |

| 2011 | Aimé Césaire | 1913–2008 | Writer and politician | — |  |

Commemorative plaque installed April 6, 2011; Césaire is buried in Martinique. |

| 2015 | Jean Zay | 1904–1944 | Politician | Crypt IX |  |

Murdered and previously buried in Orléans. |

| 2015 | Pierre Brossolette | 1903–1944 | Resistance fighter | Crypt IX |  |

Ashes transferred to the Panthéon from Père Lachaise Cemetery on May 27, 2015. |

| 2015 | Germaine Tillion | 1907–2008 | Resistance fighter | Crypt IX |  |

Symbolic burial. Her coffin contains soil from her gravesite, not her remains, as her family did not want the body moved. |

| 2015 | Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz | 1920–2002 | Resistance fighter | Crypt IX |  |

Symbolic burial. Her coffin contains soil from her gravesite, not her remains, as her family did not want the body moved. |

| 2018 | Simone Veil | 1927–2017 | Politician, Holocaust survivor | Crypt VI |  |

Originally buried at Montparnasse Cemetery. |

| 2018 | Antoine Veil | 1926–2013 | Husband of Simone Veil | Crypt VI |  |

Transferred to the Panthéon with his wife Simone Veil. Originally buried at Montparnasse Cemetery. |

| 2020 | Maurice Genevoix | 1890–1980 | Writer | Crypt XIII |  |

Originally buried at Passy Cemetery. |

| 2021 | Josephine Baker | 1906–1975 | Resistance fighter, entertainer, civil rights activist | Crypt XIII |  |

Symbolic burial. Her coffin contains soil from her birthplace, France, and her final resting place. |

| 2024 | Missak Manouchian | 1906–1944 | Resistance fighter | Crypt XIII | To be interred on February 21, 2024, with his wife Mélinée. | |

| 2024 | Mélinée Manouchian | 1913–1989 | Resistance fighter, wife of Missak Manouchian | Crypt XIII |

See also

- List of tourist attractions in Paris

- Pantheon, Rome

- Panteón Nacional, Caracas

- Pantheon, Moscow

- Church of Santa Engrácia, Lisbon

- The Apotheosis of Washington – dome fresco of the US Capitol

- Listing of the work of Jean Antoine Injalbert-French sculptor Sculptor of statue of Mirabeau.

- History of early modern period domes

- List of tallest domes

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |