Louis Braille facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis Braille

|

|

|---|---|

Bust of Louis Braille by Étienne Leroux at the Bibliothèque nationale de France

|

|

| Born | 4 January 1809 Coupvray, France

|

| Died | 6 January 1852 (aged 43) Paris, France

|

| Resting place | Panthéon, Paris and Coupvray |

| Parent(s) | Monique and Simon-René Braille |

Louis Braille (born January 4, 1809 – died January 6, 1852) was a French teacher. He invented a special system of reading and writing for people who are blind or have low vision. This system is still used today and is known all over the world as braille.

When Louis was three years old, he had an accident. He was playing with a sharp tool in his father's workshop. The tool poked him in one eye. An infection started and spread to both eyes, making him completely blind. Back then, there weren't many ways for blind people to learn. But Louis was very smart. He got a scholarship to the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in France. While he was still a student, he started creating his dot-based system. It would help blind people read and write quickly. He was inspired by a secret military code. Braille showed his new system to his friends for the first time in 1824.

As an adult, Louis Braille became a professor at the Institute. He also loved music and was a talented musician. He spent most of his life making his braille system even better. For many years after he died, most teachers didn't use it. But now, braille is seen as a truly amazing invention. It has been changed to work for languages all around the world.

Contents

Louis Braille's Early Life

Louis Braille was born in Coupvray, France, on January 4, 1809. This small town is about twenty miles east of Paris. He lived with his parents, Simon-René and Monique, and his three older siblings. His family owned land and vineyards in the countryside. Louis's father was a successful leather worker. He made things like horse tack (equipment for horses).

As soon as Louis could walk, he loved playing in his father's workshop. When he was three, he was playing with tools. He tried to make holes in a piece of leather with a sharp tool called an awl. He pressed down hard, and the awl slipped. It stabbed him in one eye. A local doctor tried to help, and a surgeon in Paris saw him the next day. But they couldn't save the eye. Louis was in pain for weeks as the wound got badly infected. He eventually lost sight in his other eye too, probably because the infection spread.

Louis Braille survived the infection. But by the age of five, he was completely blind in both eyes. Because he was so young, he didn't understand at first that he had lost his sight. He often asked why it was always dark. His parents did something special for that time. They tried hard to raise him like any other child. He grew up well in their care. He learned to find his way around the village and country paths. He used canes his father made for him. Louis seemed to accept his blindness. His smart and creative mind impressed local teachers and priests. They helped him get a good education.

Louis Braille's Education

Braille studied in Coupvray until he was ten years old. Because he was so smart and hardworking, he was allowed to go to a special school. It was one of the first schools for blind children in the world. This was the Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris. Today, it's called the National Institute for Blind Youth. Louis left home for the school in February 1819. At that time, the Royal Institute didn't have much money. It was a bit run-down. But it gave blind children a safe place to learn and be together.

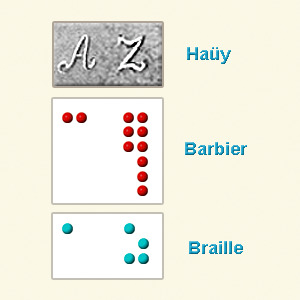

The Haüy Reading System

The children at the school learned to read using a system. It was created by the school's founder, Valentin Haüy. Haüy himself was not blind. He was a kind person who wanted to help blind people. He made a small library of books for the children. He used a method of pressing thick paper to make Latin letters stick out. Readers would move their fingers over the raised letters. They could understand the text slowly. Haüy liked this method because it was similar to traditional reading.

Braille found the Haüy books helpful. But he was also sad because they didn't have much information. The raised letters were made in a difficult way. Wet paper was pressed against copper wire. This meant the children couldn't "write" by themselves. So Louis's father, Simon-René, made him an alphabet from thick leather pieces. This let young Louis send letters home. It was slow, but he could at least trace the letters and write his first sentences.

The Haüy books were big and heavy for children. They were hard to make, very delicate, and expensive. When Haüy's school first opened, it only had three books. Still, Haüy strongly promoted their use. To him, the books seemed like the best way for blind people to read. But Braille and his classmates knew the books had big problems. Even so, Haüy's efforts were a breakthrough. They showed that the sense of touch could be used for reading without sight. The main problem with Haüy's system was that it was "talking to the fingers with the language of the eye." This means it used letters designed for seeing, not for touching.

Braille as a Teacher and Musician

Braille read the Haüy books many times. He also paid close attention to what his teachers said. He was a very good student. After he finished all the school's lessons, he was asked to stay as a teacher's helper. By 1833, he became a full professor. For most of his life, Braille stayed at the Institute. He taught history, geometry, and algebra there.

Braille had a great ear for music. He became a skilled cellist and organist. He learned from classes taught by Jean-Nicolas Marrigues. Later in life, his musical talent led him to play the organ for churches across France. Braille was a very religious Catholic. He was the organist at the Church of Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs in Paris from 1834 to 1839. Later, he played at the Church of Saint-Vincent-de-Paul.

The Braille System

Braille was determined to create a reading and writing system. He wanted it to help blind people communicate better with those who could see. He once said: "Being able to communicate is like having access to knowledge. This is super important for us [the blind]. We don't want to be looked down on or treated like we need pity. We must be treated as equals. And communication is how we can make that happen."

How Braille Started

In 1821, Braille learned about a communication system. It was made by Captain Charles Barbier of the French Army. Some stories say Braille heard about it from a newspaper. Others say Captain Barbier visited the school himself. Either way, Barbier happily shared his invention. He called it "night writing". It was a code of dots and dashes pressed into thick paper. Soldiers could feel these bumps with their fingers. This let them share information on the battlefield without light or talking. Barbier's code was too complicated for military use. But it gave Braille the idea to create his own system.

Designing the Braille System

Braille worked very hard on his ideas. His system was mostly finished by 1824, when he was fifteen years old. He took Barbier's "night writing" and made it simpler and more effective. He created a standard pattern for each letter. He also reduced the twelve raised dots to just six. He first published his system in 1829. By the second version in 1837, he removed the dashes. They were too hard to read. Most importantly, Braille's smaller dot patterns could be recognized as letters with just one touch of a finger.

Braille created his raised-dot system using an awl. This was the same kind of tool that had blinded him. While designing his system, he also made tools to use it easily. These were based on Barbier's own slate and stylus tools. Braille added two metal strips to the slate. This created a secure area for the stylus. It helped keep the lines straight and easy to read.

With these simple tools, Braille built a strong communication system. Dr. Richard Slating French, a former director of the California School for the Blind, wrote that it "shows genius, like the Roman alphabet itself."

Braille for Music

The braille system was soon expanded to include braille musical notation. Braille loved music himself. He carefully planned the music code. He wanted to make sure it was "flexible enough to work for any instrument." In 1829, he published the first book about his system. It was called Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs by Means of Dots, for Use by the Blind and Arranged for Them. It's interesting that this book was first printed using the raised letter method of the Haüy system.

Braille's Publications

Braille wrote several books about his system and for the education of blind people. His book Method of Writing Words, Music, and Plain Songs... (1829) was updated and printed again in 1837. His math guide, Little Synopsis of Arithmetic for Beginners, was used starting in 1838. His detailed study New Method for Representing by Dots the Form of Letters, Maps, Geometric Figures, Musical Symbols, etc., for Use by the Blind was first published in 1839. Many of Braille's original printed works are still at the Braille birthplace museum in Coupvray.

Decapoint System

In New Method for Representing by Dots... (1839), Braille also shared his idea for a new writing system. This system would let blind people write letters that sighted people could read. It was called decapoint. This system combined his dot-punching method with a special grill he designed. This grill would be placed over the paper. When used with a special number table (which Braille also designed and required memorizing), the grill allowed a blind writer to accurately create standard alphabet letters.

After creating decapoint, Braille helped his friend Pierre-François-Victor Foucault. Foucault was working on his Raphigraphe. This was a machine that could press letters onto paper, like a typewriter. Foucault's machine was a big success. It was shown at the World's Fair in Paris in 1855.

Louis Braille's Later Life

Braille's students admired and respected him. But his writing system was not taught at the Institute during his lifetime. The leaders who followed Valentin Haüy (who died in 1822) did not want to change the school's old methods. In fact, they were against using braille. Dr. Alexandre François-René Pignier, the headmaster, was even fired after he had a history book translated into braille.

Braille had always been a sickly child. His health got worse as he grew older. He suffered from a serious lung illness for 16 years. People believed it was tuberculosis. Even though there was no cure then, he lived with it for a long time. By the age of 40, he had to stop teaching. When his condition became very dangerous, he was taken to the hospital at the Royal Institution. He died there in 1852, two days after his 43rd birthday.

Louis Braille's Legacy

The blind students at the Institute strongly insisted on using Braille's system. Finally, it was adopted by the school in 1854, two years after his death. The system spread quickly in French-speaking countries. But it took longer to spread elsewhere. However, by 1873, at the first European meeting of teachers for the blind, Dr. Thomas Rhodes Armitage strongly supported braille. After that, its use around the world grew fast. By 1882, Dr. Armitage could say that "There is now probably no institution in the civilized world where braille is not used except in some of those in North America." Eventually, even these places started using it. Braille was officially adopted by schools for the blind in the United States in 1916. A universal braille code for English was made official in 1932.

New types of braille technology keep appearing. These include things like braille computer screens and the RoboBraille email service. There's also Nemeth Braille, a full system for math and science symbols. Almost 200 years after it was invented, braille is still a very powerful and useful system.

Honors and Tributes to Louis Braille

The huge impact of Louis Braille was described in a 1952 essay by T.S. Eliot. He wrote:

"Perhaps the greatest honor to Louis Braille is how we use his name for the writing system he invented. We honor Braille when we speak of braille. His memory is more secure than many famous people from his time."

Braille's childhood home in Coupvray is now a historic building. It houses the Louis Braille Museum. A large monument to him was put up in the town square. The square itself was renamed Braille Square. On the 100th anniversary of his death, his body was moved to the Panthéon in Paris. This is a special place where famous French people are buried. In a symbolic gesture, Braille's hands were left in Coupvray. They were buried with respect near his home.

Statues and other memorials to Louis Braille can be found all over the world. He has been honored on postage stamps worldwide. An asteroid called 9969 Braille was named after him in 1992. The Encyclopædia Britannica lists him among the "100 Most Influential Inventors Of All Time."

The 200th anniversary of Braille's birth in 2009 was celebrated globally. There were exhibitions and talks about his life and achievements. Belgium and Italy made 2-euro coins to honor him. India released two special coins (Rs 100 and Rs 2). The USA made a one-dollar coin. All these coins honored Braille.

World Braille Day is celebrated every year on Braille's birthday, January 4.

Louis Braille in Popular Culture

Because of his amazing achievements as a young boy, Braille is seen as a hero for children. Many books for young people have been written about him. He has also appeared in other art forms. These include the American TV special Young Heroes: Louis Braille (2010). There's also the French TV movie Une lumière dans la nuit (2008), released in English as The Secret of Braille. The play Braille: The Early Life of Louis Braille (1989) was written by Lola and Coleman Jennings. In music, the song Merci, Louis is about Braille's life. It was composed by Terry Kelly, a singer-songwriter from Halifax, Canada. He is also the chair of the Canadian Braille Literacy Foundation. The Braille Legacy, a musical about Louis Braille, opened in April 2017. It was directed by Thom Southerland and starred Jérôme Pradon.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Louis Braille para niños

In Spanish: Louis Braille para niños