Paris Commune facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Paris Commune |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War | |||||||

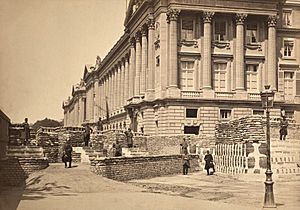

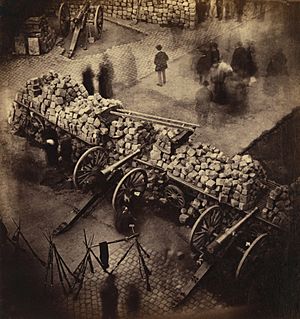

A barricade thrown up by Communard National Guard on 18 March 1871. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

National Guards |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 170,000 | 25,000–50,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 877 killed, 6,454 wounded, and 183 missing | 6,667 confirmed killed and buried; unconfirmed estimates from 10 to 15,000 to as high as 20,000 dead. Forty-three thousand were taken prisoner, and 6,500 to 7,500 self-exiled abroad. | ||||||

The Paris Commune (French: Commune de Paris) was a revolutionary government that took control of Paris in France. It ruled the city from March 18 to May 28, 1871. This happened after France lost the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71).

During the war, the National Guard defended Paris. Many of its soldiers were working-class and had strong political ideas. After France's defeat and the creation of the Third Republic, these soldiers took over Paris. They refused to accept the new government's authority and tried to create their own independent government.

The Commune governed Paris for about two months. It introduced many new rules that were very progressive for the time. These included separating the church from the government, allowing people to manage their own communities, cancelling rent payments, and stopping child labor. They also gave workers the right to take over businesses if the owner left. Many churches and religious schools were closed. Groups like feminists, socialists, communists, and anarchists were very important in the Commune. However, they only had a short time to achieve their goals.

The French national army eventually stopped the Commune in late May 1871. This period is known as La semaine sanglante ("The Bloody Week"). The army killed many Communards, and thousands more were taken prisoner or fled the country. In its final days, the Commune also executed some hostages, including the Archbishop of Paris. Most prisoners and exiles were later pardoned in 1880 and could return home.

The Paris Commune greatly influenced thinkers like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. They saw it as the first example of a "dictatorship of the proletariat," meaning a government run by the working class.

Contents

Why the Commune Started

France Loses the War

On September 2, 1870, France lost a major battle at Sedan. Emperor Napoleon III was captured. When Parisians heard this, they were very angry. The Empress fled, and the government quickly fell apart. New leaders declared a French Republic and formed a government to continue the war. But the Prussian army quickly surrounded Paris.

By September 20, 1870, the German army had completely surrounded Paris. The regular French army in Paris had only about 50,000 soldiers. Most French soldiers were either prisoners or trapped elsewhere. The city's defense relied heavily on the National Guard.

The National Guard had about 300,000 men. They were not well-trained or experienced. Units from wealthier areas supported the government, while those from working-class neighborhoods were more radical. These working-class guardsmen often refused to wear uniforms or obey orders without discussion. They demanded to elect their own officers. These radical National Guard members became the main fighting force of the Commune.

Paris Under Siege

As the Germans surrounded Paris, radical groups saw that the government was weak. They started protesting. On September 19, National Guard units from working-class areas marched to the city center. They demanded a new government, a "Commune." They were met by loyal army units and eventually left peacefully. Later, on October 5, 5,000 protesters demanded immediate elections and rifles. On October 8, thousands more, led by Eugène Varlin, marched chanting "Long Live the Commune!" These protests also ended without violence.

In October, the French army tried to break the German siege but failed. Communication with the outside world was cut. On October 6, the Defense Minister left Paris by hot-air balloon to organize resistance.

Uprising on October 31

On October 28, news arrived that 160,000 French soldiers had surrendered at Metz. Another attempt to break the siege of Paris also failed. On October 31, radical leaders called for new protests at the Hôtel de Ville. Fifteen thousand people gathered, some armed, demanding a Commune. Shots were fired, and protesters entered the building.

The most radical leader, Blanqui, tried to set up his own government. However, National Guard units loyal to the government arrived and took back the building peacefully. The uprising ended quickly. On November 3, Parisians voted on whether they trusted the government. Most voted "yes." Two days later, local elections were held, and some radical candidates won, including Georges Clemenceau.

Peace Talks and Hard Times

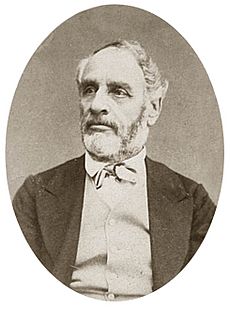

Adolphe Thiers, a conservative leader, traveled around Europe. He found no country willing to help France against Germany. He reported that France had to negotiate a ceasefire. He met with Bismarck on November 1. Bismarck demanded that France give up land and pay huge amounts of money. The French government decided to keep fighting.

Life in Paris became very hard during the siege. Temperatures dropped, and the Seine River froze. People suffered from shortages of food, wood, coal, and medicine. The city was dark at night. Communication was only by balloon or carrier pigeon. People ate zoo animals and rats because there was no other food.

By January 1871, the Germans began to bombard Paris day and night. Hundreds of shells hit the city daily.

January Uprising and Armistice

Between January 11 and 19, 1871, French armies were defeated on four fronts. Paris was starving. General Trochu received reports that anger against the government was growing in working-class neighborhoods.

On January 22, hundreds of National Guards and radicals gathered outside the Hôtel de Ville. They demanded that the military be controlled by civilians and that a commune be elected. Gunfire broke out, and six protesters were killed. The army cleared the square. The government banned two radical newspapers and arrested 83 revolutionaries.

At the same time, French leaders in Bordeaux realized the war could not continue. On January 26, they signed a ceasefire. Paris would not be occupied by Germans. Regular soldiers would give up their arms, but the National Guard would keep theirs to maintain order.

New Elections and Thiers

The national government called for elections on February 8. Most voters in France were rural and conservative. Out of 645 elected officials, about 400 wanted a king. About 200 were republicans. Adolphe Thiers was the most popular candidate, elected in 26 areas.

On February 17, Thiers, aged 74, was chosen as the chief executive of the Third Republic. He was seen as the best person to bring peace and order. Thiers convinced Parliament that peace was necessary. He signed the armistice on February 24.

The Commune Takes Control

Fight Over Cannons

After the war, Paris had 400 old bronze cannons. Parisians had paid for these cannons themselves. The new Central Committee of the National Guard, now controlled by radicals, moved the cannons to working-class areas. They wanted to keep them from the regular army and protect the city. Thiers wanted the cannons under government control.

Clemenceau tried to find a middle ground, but neither side agreed. Thiers wanted to restore order quickly. The government also refused to extend a pause on debt payments and shut down two radical newspapers. Thiers decided to move the government from Bordeaux to Versailles, not Paris. This angered the National Guard even more.

On March 17, Thiers and his cabinet decided to send the army to take the cannons the next day. Some generals thought it was too soon, as the army was weak and many soldiers were unreliable. But Thiers insisted on a surprise attack. If it failed, the government would retreat to Versailles, gather more troops, and then attack Paris with full force.

Failed Army Attempt and Retreat

Early on March 18, two army brigades went to Montmartre, where 170 cannons were located. A few National Guards were there. A general ordered his soldiers to fire, but they refused. Word spread, and more National Guards and citizens arrived. The army units became surrounded and started joining the crowd.

The general and his officers were captured by the guardsmen and mutinous soldiers. They were taken to a local headquarters. Later that afternoon, another general, Jacques Leon Clément-Thomas, was recognized and arrested. He was hated by the National Guards for his strict discipline. Around 5:30 PM, both generals were killed by the angry crowd.

By late morning, the army's plan to take the cannons had failed. Crowds and barricades appeared in all working-class neighborhoods. The army was ordered to retreat. Thiers began moving the government to Versailles.

On the afternoon of March 18, the Central Committee of the National Guard ordered its battalions to seize the Hôtel de Ville. They didn't know that Thiers and the government had already left for Versailles. The National Guard quickly took control of key government buildings. By the next morning, the Central Committee was meeting at the Hôtel de Ville. A red flag was raised over the building.

Some radical members wanted to march on Versailles immediately. But the majority wanted to establish their authority in Paris first. They lifted the state of siege, formed commissions to run the government, and called for elections on March 23. They also sent a group of Paris mayors to negotiate with Thiers for special independence for Paris.

On March 22, demonstrators supporting peace were blocked by guardsmen at Place Vendôme. After shots were fired, the guardsmen opened fire on the crowd. This event was called the Massacre in the Rue de la Paix.

Commune Elections

Tension grew between the elected republican mayors and the National Guard's Central Committee. On March 22, the Committee declared itself the true government of Paris. It took over city halls from the mayors. Clemenceau complained, "We are caught between two bands of crazy people."

Elections for the Commune council were held on March 26. One member was elected for every 20,000 residents. Only 233,000 out of 485,000 registered voters participated. Turnout was low in wealthy areas but high in working-class neighborhoods. About 20 moderate republicans refused to take their seats. In the end, the council had 60 members. Most were radical revolutionaries, socialists, or anarchists. All members were men, as women were not allowed to vote. The winners were announced on March 27, followed by a large celebration with the National Guard.

How the Commune Was Organized

The new Commune had its first meeting on March 28. They voted on many ideas, including ending the death penalty and military service. They also said that being a member of the Commune meant you couldn't be in the National Assembly. This led some moderate members to resign. The Commune decided its discussions would be secret, as they were at war with Versailles.

The Commune had no single president or commander. It set up nine commissions to manage Paris, overseen by an Executive Commission. One of its first rules was that military service was abolished. Also, no military force other than the National Guard could be in Paris. All healthy men were part of the National Guard. This system had a problem: the National Guard had two commanders, making it unclear who was in charge of the coming war.

What the Commune Did

New Rules and Policies

The Commune used the old French Republican Calendar and a red flag instead of the French tricolor. Despite disagreements, the council worked to organize public services for Paris's two million residents. They agreed on policies that aimed for a progressive and democratic society. Since the Commune only lasted about two months, only some of its decrees were fully put into action. These included:

- Separating the church from the government.

- Cancelling rent payments during the siege.

- Ending child labor and night work in bakeries.

- Giving money to the families of National Guardsmen killed in service.

- Returning all pawned tools and household items worth up to 20 francs for free.

- Delaying business debt payments and ending interest on debts.

- Giving employees the right to take over businesses if the owner left, with the old owner still getting paid later.

- Stopping employers from fining their workers.

The Commune's rules took away state money from the Church and seized church property. Religious education was removed from schools. Churches could only hold religious activities if they also held public political meetings in the evenings. Many churches were closed, and priests were arrested as hostages.

The Commune leaders had huge workloads. They had to manage many parts of the government and military. Many local groups helped meet social needs, like providing food and first aid. For example, in one area, school supplies were free, and an orphanage was set up. In another, schoolchildren received free clothes and food. These local groups often followed the lead of local workers.

Women's Efforts

Women played a big part in starting and running the Commune, even though they couldn't vote or be elected. They helped build barricades and cared for wounded fighters.

Some women started a feminist movement. Nathalie Lemel and Élisabeth Dmitrieff created the Women's Union for the Defence of Paris and Care of the Wounded on April 11, 1871. This group believed women's lives would only improve by fighting against capitalism. They demanded equal rights and equal pay, the right for women to divorce, and secular education for girls. Nathalie Lemel also helped create a cooperative restaurant that gave free food to the poor.

Paule Minck opened a free school and ran a political club in a church. Anne Jaclard started a newspaper and was part of a local watch committee with Louise Michel and Paule Minck. Louise Michel, known as the "Red Virgin of Montmartre," was a symbol of women's active role in the Commune. A women's battalion of the National Guard even defended a public square during the army's attack.

The Bank of France

The Commune put François Jourde in charge of its finances. Jourde was careful with money. Paris's tax money was 20 million francs, plus six million seized from the Hôtel de Ville. The Commune's expenses were 42 million, mostly for paying the National Guard. Jourde got a loan from the Rothschild Bank and used city funds.

The gold reserves of the Bank of France had been moved out of Paris for safety. But 88 million francs in gold coins and 166 million in banknotes were still in Paris. When the Thiers government left, they couldn't take the money. The reserves were guarded by 500 National Guards who worked for the bank. Some Communards wanted to take the bank's money for social projects. But Jourde argued that without the gold, the currency would collapse. The Commune appointed Charles Beslay to deal with the bank. He arranged for the bank to loan the Commune 400,000 francs a day. Thiers approved this, as he needed the gold to keep the French currency stable and pay Germany.

Against the Church

From the start, the Commune was hostile towards the Catholic Church. On April 2, it passed a rule accusing the Church of "complicity in the crimes of the monarchy." This rule separated the church from the government, took away state money for the Church, seized church property, and ordered Catholic schools to stop religious education.

Over the next seven weeks, about 200 priests, nuns, and monks were arrested. Twenty-six churches were closed. Some churches, like Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois, became socialist meeting clubs. Later, some political clubs demanded the execution of Archbishop Darboy and other priests. The Archbishop and several priests were executed during the Bloody Week. This was in response to the army executing Commune soldiers.

Destroying Symbols

One major event was the destruction of the Vendôme Column. This column honored Napoleon I's victories and had a statue of him on top. On April 12, the Commune's executive committee voted to destroy it. They called it a "monument of barbarism" and a "symbol of brute force." The idea came from painter Gustave Courbet. The column was ceremonially pulled down on May 16. Red flags were draped over its base. Pieces of the statue were melted down to make coins.

On May 12, a crowd organized by the Commune also destroyed the home of Adolphe Thiers, the leader of the Third Republic.

War with the Government

Failed Attack on Versailles

In Versailles, Thiers needed 150,000 soldiers to retake Paris. He only had about 20,000 reliable soldiers and 5,000 police. He quickly built a new army, mostly from French prisoners of war released by Germany. He chose Patrice MacMahon to lead this army. MacMahon was popular and had been wounded in battle. By March 30, the army began fighting the National Guard outside Paris.

In Paris, Commune leaders decided on April 1 to attack the army in Versailles within five days. The attack began on April 2. Five battalions crossed the Seine River but were quickly pushed back by the army. About twelve Commune soldiers were killed.

Despite this failure, Commune leaders still believed the French army would not fire on National Guardsmen. They prepared a huge attack with 27,000 guardsmen. They marched on April 3 without cavalry, artillery, or supplies. They thought the forts outside the city were held by their own men, but the army had taken them back. The National Guard came under heavy fire, broke ranks, and fled back to Paris. Army units often shot captured guardsmen.

Hostage Decree

The Commune leaders responded to the army's executions by passing the Decree on Hostages on April 5. This rule said that anyone accused of helping the Versailles government could be arrested and tried. Those found guilty would become "hostages of the people of Paris." Article 5 stated that if the army executed a Commune prisoner, three hostages would be executed in return.

Under this rule, several religious leaders were arrested, including Archbishop Georges Darboy of Paris. The National Assembly in Versailles responded by passing a law allowing military courts to judge and punish suspects within 24 hours. About 100 hostages, including the Archbishop, were shot by the Commune before it fell.

Growing Radicalism

By April, as MacMahon's army neared Paris, the Commune argued about whether to focus on military defense or social reforms. The majority, including radicals, wanted to prioritize the military. They voted to create a Committee of Public Safety, like the one from the French Revolution's "Reign of Terror." Many Commune members opposed this name because of its violent history.

The committee was given wide powers to arrest enemies of the Commune. Led by Raoul Rigault, it arrested many people suspected of treason or insulting the Commune. High religious officials were arrested. The policy of holding hostages was criticized by some, including Victor Hugo. On April 12, Rigault offered to exchange Archbishop Darboy and other priests for Blanqui, who was in prison. Thiers refused. On May 14, Rigault offered to exchange 70 hostages, but Thiers refused again.

National Guard's Strength

Every able-bodied man in Paris was supposed to be in the National Guard. On paper, the Commune had about 200,000 men on May 6. But the actual number was much lower, likely between 25,000 and 50,000. By early May, 20% of the National Guard were absent.

The National Guard had hundreds of cannons and thousands of rifles. But only half the cannons and two-thirds of the rifles were ever used. Few guardsmen were trained to use the heavy naval cannons on the city walls. The number of trained artillerymen dropped sharply.

National Guard officers were elected by the soldiers, so their leadership skills varied. Some Polish exiles, who had fought against Russia, played important roles. General Jaroslav Dombrowski, a Polish noble and former Russian army officer, became commander of the Commune forces. He held this position until he was killed on May 23 while defending barricades.

Fort Issy Falls

Fort Issy, south of Paris, was a key point blocking the army's path into the city. Its commander was Leon Megy, a former mechanic and radical. The army began a heavy bombardment of the fort. General Cissey offered to spare the defenders' lives if they surrendered. On April 29–30, most soldiers left the fort. But the National Guard quickly sent reinforcements and re-occupied it.

General Cluseret, commander of the National Guard, was fired and imprisoned. General Cissey continued bombarding the fort. The defenders held out until May 7–8, then withdrew. The new commander, Louis Rossel, announced, "The tricolor flag flies over the fort of Issy, abandoned yesterday by the garrison." Rossel was then dismissed and replaced by Delescluze, a journalist with no military experience.

Bitter fighting continued as MacMahon's army moved closer to the walls of Paris. On May 20, the army's artillery bombarded western Paris. Dombrowski reported that his soldiers were retreating. He had few men left and lacked artillerymen. On May 19, the Commune learned that MacMahon's forces were inside Paris.

"Bloody Week"

May 21: Army Enters Paris

MacMahon's final attack on Paris began on Sunday, May 21. Soldiers found an undefended section of the city wall. An army engineer confirmed it, and MacMahon ordered his troops in. Two battalions entered without resistance. By 4 AM, 50,000 soldiers were inside the city.

When Commune leader Delescluze heard the army was inside, he didn't believe it at first. He refused to ring the warning bells until the next morning. General Dombrowski asked for reinforcements and a counterattack, saying, "Remain calm, and everything will be saved." Many National Guards blamed Dombrowski, but these rumors stopped when he died two days later from wounds received on the barricades.

May 22: Barricades and Street Fights

On the morning of May 22, bells finally rang. Delescluze issued a call to arms, urging Parisians to fight. The Committee of Public Safety also called for barricades.

Despite these calls, only 15,000 to 20,000 people, including women and children, responded. The Commune's forces were outnumbered five to one. The strong neighborhood loyalties, once a strength, became a weakness. Each area fought for itself instead of as a unified defense. The wide boulevards of Paris, built by Haussmann, made street fighting harder for the Commune. The army had a central command and better tactics. They avoided direct attacks on barricades, instead tunneling through houses to get behind them. Most barricades were abandoned without a fight.

By May 22, the army had taken a large area of western Paris. Little resistance was met there, but the army moved slowly. Only a few large barricades were ready. About 900 barricades were quickly built from paving stones. The first serious fighting was an artillery duel between the army and the National Guard. On the same day, the army began executing captured National Guard soldiers.

May 23: Battle for Montmartre; Palaces Burn

On May 23, the army's next target was Montmartre, where the uprising began. The National Guard had built barricades there. The cannons captured earlier were still there, but they had no ammunition or trained gunners.

One barricade was defended by about 30 women, including Louise Michel. She was captured but escaped. She later surrendered to protect her mother. The National Guard was no match for the army. By midday, soldiers were at the top of Montmartre. They captured 42 guardsmen and several women, took them to the house where the generals had been killed, and shot them. On Rue Royale, soldiers took a barricade, and 300 prisoners were shot there.

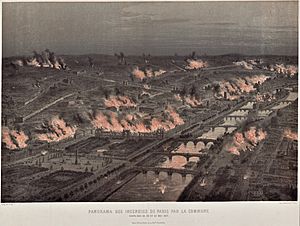

That day, National Guardsmen, frustrated by the fighting, began burning public buildings. They set fire to buildings near Rue Royale and Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Many other buildings were also burned.

The Tuileries Palace, home to French monarchs for centuries, was defended by 300 National Guards. After a day-long fight, the commander ordered the palace burned. It was soaked with oil and turpentine, and gunpowder barrels were placed inside. The fire lasted 48 hours and destroyed most of the palace. The commander sent a message: "The last vestiges of royalty have just disappeared." The Richelieu library of the Louvre was also burned and destroyed. The rest of the Louvre was saved by museum staff and firefighters. Most major fires were started by the National Guard and other Commune groups.

May 24: Hôtel de Ville Burns; Executions

At 2 AM on May 24, National Guardsmen set fire to the Hôtel de Ville, the Commune's headquarters. Wounded men were being treated there, and some Commune members were trying to escape. Delescluze ordered everyone to leave before it was burned.

Battles continued on May 24 under a sky black with smoke. There was no central plan for the Commune's defense. Each neighborhood fought alone. The National Guard fell apart, with many soldiers fleeing. Only 10,000 to 15,000 Communards remained to defend the barricades. More public buildings were set on fire, including the Palais de Justice and the Police Prefecture.

As the army advanced, they continued to execute captured Communard soldiers. Informal military courts were set up. Prisoners' hands were checked for weapon use. Sentences were given quickly, and executions happened immediately.

In response to the army's executions, the Communards carried out their own. Raoul Rigaut, head of the Committee of Public Safety, executed four prisoners before he was captured and shot. On May 24, National Guardsmen demanded the execution of hostages at La Roquette prison. The Commune's prosecutor, Théophile Ferré, ordered six hostages executed. These included Archbishop Georges Darboy and three priests. They were taken to the prison courtyard and shot.

May 25: Delescluze Dies

By the end of May 24, the army controlled most of Paris. The Commune held only a few eastern districts. Delescluze and the remaining Commune leaders were at a city hall. A fierce battle took place between 1,500 National Guardsmen and three army brigades.

On May 25, the insurgents lost the city hall. Delescluze offered command of the Commune forces to Walery Antoni Wróblewski, a Polish exile, but he refused. Around 7:30 PM, Delescluze, wearing his red sash, walked unarmed to a barricade. He climbed to the top and was immediately shot dead.

May 26: Bastille Captured; More Executions

On the afternoon of May 26, after six hours of heavy fighting, the army captured the Place de la Bastille. The National Guard still held some areas and had artillery at Buttes-Chaumont and Père-Lachaise.

A group of National Guardsmen went to La Roquette prison and demanded the remaining hostages. These included ten priests, 35 police, and two civilians. They took them to Rue Haxo. According to a Commune defender, 63 people were executed by the Commune during the Bloody Week.

May 27–28: Final Battles and Executions

On the morning of May 27, the army attacked the National Guard artillery at Buttes-Chaumont. The heights were captured by the French Foreign Legion. One of the last strongholds was the Père-Lachaise Cemetery, defended by about 200 men. At 6 PM, the army stormed the cemetery. Fierce fighting took place among the tombs. The last Communards were captured and shot against a cemetery wall. This wall is now called the Communards' Wall. One woman was among those executed there.

On May 28, the army captured the remaining Commune positions with little resistance. In the morning, the army took La Roquette prison and freed 170 hostages. The army captured 1,500 prisoners at Rue Haxo and 2,000 more near Père-Lachaise. A few barricades held out until the afternoon, then all resistance ended.

What Happened Next

The Paris Commune inspired other uprisings around the world. Leaders like Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin admired it greatly. Lenin even celebrated when his Bolshevik government lasted longer than the Commune. The term "Commissar" used by the Bolsheviks came from the Commune.

On July 24, 1873, the National Assembly decided to build the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur on Montmartre. This was near where the generals were killed. It was meant to "make up for the crimes of the Commune." A church and a plaque mark the spot on Rue Haxo where 50 hostages were shot.

A plaque also marks the Communards' Wall in Père Lachaise Cemetery, where 147 Communards were executed. People hold annual ceremonies there to remember the Commune. Another plaque behind the Hôtel de Ville marks a mass grave of Communards.

Several places are named after the Paris Commune, like a square in Paris, a street in Berlin, Germany, and a square in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

The Paris Commune was a big topic during China's Cultural Revolution. Mao Zedong saw it as a model for revolution. Leaders of the Cultural Revolution wanted to learn from the Commune's focus on everyday life and mass participation.

Pol Pot, leader of the Khmer Rouge, was also inspired by the Commune. He believed it failed because it didn't fully control the rich.

In 2021, Paris celebrated the Commune's 150th anniversary with exhibitions, lectures, and concerts. The Mayor of Paris planted a tree from New Caledonia in Montmartre. Thousands of Communards were sent to New Caledonia after the Commune was crushed.

The Commune still causes strong feelings. In May 2021, a procession of Catholics honoring the executed Archbishop was attacked by a far-left group also celebrating the Commune's anniversary.

Other Communes of 1871

Soon after the Paris Commune took power, revolutionary groups in other French cities tried to start their own communes. The Paris Commune sent people to encourage them. The longest-lasting commune outside Paris was in Marseille, from March 23 to April 4. It was stopped with some fighting. Most other communes lasted only a few days and ended peacefully.

Key Figures After the Commune

- Adolphe Thiers became the first President of the French Third Republic in August 1871. He was later replaced by Patrice MacMahon. When Thiers died in 1877, his funeral was a huge event, with a million Parisians lining the streets. He is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

- Patrice MacMahon, who led the army against the Commune, served as President from 1873 to 1879. He was buried with military honors when he died in 1893.

- Georges Clemenceau, the mayor of Montmartre during the Commune, became a leader of the Radical Party. He was Prime Minister of France during World War I and signed the peace treaty.

Some Commune leaders died fighting, but many survived and continued their political careers. Between 1873 and 1876, about 1,000 Communards were sent to a prison colony in New Caledonia.

- Felix Pyat, a Commune leader, escaped Paris during the Bloody Week. He was sentenced to death but went into exile in England. After a general pardon in 1881, he returned to Paris and was elected to the French Parliament.

- Louis Auguste Blanqui was the honorary President of the Commune but was in prison the whole time. He was later imprisoned but continued to be an activist after his release. He died in 1881 and is buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

- Louise Michel, the "Red Virgin," was sent to New Caledonia. She returned to Paris after the pardon in 1880 and continued her work as an anarchist. She was arrested several more times but was sometimes freed with help from Georges Clemenceau. She died in 1905.

- Adrien Lejeune, the last surviving Communard, moved to the Soviet Union in 1928 and died there in 1942.

The Commune in Stories and Art

Poems

- Victor Hugo wrote "Sur une barricade" in 1871, honoring a brave twelve-year-old Communard.

- William Morris's poem series "The Pilgrims of Hope" (1885) ends during the Commune.

Novels

- Jules Vallès wrote a trilogy about the Commune, published after his death.

- Émile Zola's 1892 novel La Débâcle is set during the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune.

- Arnold Bennett's 1908 novel The Old Wives' Tale also takes place partly in Paris during the Commune.

- French writer Jean Vautrin's 1998 novel Le Cri du Peuple tells the story of the Commune's rise and fall.

- In The Prague Cemetery by Umberto Eco, a chapter is set during the Paris Commune.

- The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee (2016) shows a fictional opera singer surviving the siege of Paris.

- Some British and American novels of the late 1800s showed the Commune as a harsh rule. Examples include Woman of the Commune (1895) by G. A. Henty and The Red Republic (1895) by Robert W. Chambers.

- In Marx Returns by Jason Barker, the Commune is shown as a symbol of an unfinished political goal for Karl Marx.

Theatre

- Plays about the Commune include Nederlaget by Nordahl Grieg, Die Tage der Commune by Bertolt Brecht, and Le Printemps 71 by Arthur Adamov.

- A German performance group created Paris 1871 Bonjour Commune in 2010.

- The New York theatre group The Civilians performed Paris Commune in 2004 and 2008.

Film

- A notable film is La Commune (2000), directed by Peter Watkins. It is nearly six hours long and uses ordinary people instead of actors to feel like a documentary.

- Soviet filmmakers Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg directed the silent film The New Babylon (1929) about the Paris Commune.

- British filmmaker Ken McMullen made two films influenced by the Commune: Ghost Dance (1983) and 1871 (1990).

Other Arts

- Italian composer Luigi Nono wrote the opera Al gran sole carico d'amore (In the Bright Sunshine, Heavy with Love), based on the Paris Commune.

- Comics artist Jacques Tardi adapted Vautrin's novel into a graphic novel called Le Cri du Peuple.

- In the British TV series The Onedin Line (1972), a character gets caught in the Commune while trying to collect a debt.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Comuna de París para niños

In Spanish: Comuna de París para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |